5 Chapter I

Introduction

Early Image of Corpus Christi (Circa 1846)

Corpus Christi Public Library

Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi is a four-year, doctoral degree granting university with its primary campus in Corpus Christi, Texas. With almost 12,000 students, it serves as the educational hub for the Coastal Bend Region of South Texas. The University was originally founded in 1947 as a private Baptist-affiliated college and has undergone significant changes and several iterations in its 75-year history.[i]

In 1998, the former President of the University of Corpus Christi, Dr. Kenneth A. Maroney, praised then-President of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Robert Furgason for “recognizing immediately upon his arriving that there was a history here.”[ii]Maroney was correct about the rich history and keen to recognize the value in understanding the past of the institutions which shape our lives. Indeed, these two presidents led two very different universities in terms of student body, name, and character. Both leaders served during important times of transformation and continued to work on behalf of the institution after their tenure as president had concluded. They shared a common goal for advancing education through an institution that was founded 75 years ago. This book tells of the story of the Island University.

The History of Ward Island

Ward Island is a 223-acre site bordered by Oso Bay to the South and East and Corpus Christi Bay to the North.[iii] The Island overlooks Corpus Christi Bay and today has a picturesque view of Downtown Corpus Christi to the Northwest. Ocean Drive traverses the northern side of the island and connects to Naval Air Station-Corpus Christi (NAS-Corpus Christi). The Cayo del Oso shallow marshlands extend from Ocean Drive around the southern end of Ward Island to its eastern edge.[iv][v]

Earlier in its history, the area now occupied by TAMU-CC was sporadically inhabited by nomadic Native Americans who subsisted on seafood.[vi] The first people of the area that would become known as Ward Island were the Karankawa.[vii] This group lived in the Texas Gulf Coast region from present-day Galveston, south to Corpus Christi. Their name is derived from their practice of raising and keeping dogs. In their native language, the name Karankawa means “dog-lover” and refers to several bands of coastal peoples who survived on hunting, fishing, and gathering.[viii] The male Karankawa have been described as particularly tall and the people wore tattoos as well as jewelry made of shells, beads, and deerskin. They dressed in breechcloths and used animal grease on their bodies to repel insects.[ix]

Areas inhabited by the Karankawa were later occupied by European explorers followed by Mexican and U.S. settlers. The natives were not willing to be subjugated to living in missions or under the control of explorers or settlers in the area. Beginning with an encounter with the Spanish expedition of Panfilo de Narvaez in Galveston in 1528, the Karankawa had intermittent contact with the French and Spanish until the 1700s when the Spanish unsuccessfully aimed to place them into missions.[x] Encounters between the natives and Europeans more often led to violence than peaceful trade.[xi][xii]

Settlement brought about rapid declines among the native population with European diseases being particularly devastating. The European explorers, Mexicans, and later Texans all had superior weaponry to the Karankawa even though they were described as very capable with a bow and arrow.[xiii] This disparity in weaponry meant that in armed conflict the natives would suffer mass casualties. A series of conflicts with settlers, including those under Stephen F. Austin, resulted in large numbers of fatalities for the native peoples. The last conflict between the Spaniards, under Juan Nepomuceno Cortina Goseacochea, and the few remaining Karankawa occurred in 1858 near Rio Grande City in South Texas. This armed engagement resulted in the virtual extermination of these native peoples.[xiv][xv] A small number of remaining Karankawa incorporated themselves into the colonizer’s society, moved south to Mexico, or joined with other native peoples.[xvi]

Few reminders or tributes to the Karankawa people remain today. As their campsites were not permanent settlements, only small artifacts have been found. Some burial sites have been identified and have been protected. The Calhoun County Museum in Port Lavaca, Texas has a Karankawa exhibit[xvii] and a few books provide accounts of the natives.[xviii] The Boy Scouts of America operate Camp Karankawa, named after these people and is located on Lake Corpus Christi, northwest of the city.[xix]

Prior to the 1830s, written history about the region is scarce. The area surrounding Corpus Christi was sparsely populated and at times in its early history the fledgling community was almost deserted.[xx] As the few remaining native peoples of the area were previously driven south and west, the town of Corpus Christi was formed during the mid-1800s. While earlier attempts were made to establish outposts in the area, the first permanent trading post was successfully established on Corpus Christi Bay in 1839.[xxi] A trader and developer, Colonel Henry Lawrence Kinney (1814-1862), founded Nuecestown and Kinney’s Rancho which would become part of the City of Corpus Christi.[xxii] In the mid-1840s a Post Office was established, and the town of Corpus Christi became the seat of the newly formed Nueces County in 1846, just one year after Texas became a U.S. state. The city was not officially incorporated until February 16, 1852 and by 1860 reached a population of 1,200.[xxiii]

Situated on the Texas Coastal Plains, Corpus Christi is at the heart of the Coastal Bend Region. The name Coastal Bend is derived from the distinctive angular shape of the Texas shoreline as it runs in a more longitudinal orientation south beginning roughly at the point of Corpus Christi Bay and the northernmost portion of Padre Island. The area has naturally sparse vegetation with mesquite trees, cactus, and a variety of grasses being the prominent flora. Barrier islands, notably Mustang Island and Padre Island, create a series of shallow wetlands and bays. Some of these wetlands now lie inside the modern-day city limits. The area is well-known for its fishing, marine life, and numerous bird species (resident and migratory).[xxiv]

Port of Corpus Christi Texas with freighter passing under Drawbridge

Lee Russell (1939). Library of Congress, LC-USF33- 012013-MS [P&P] LOT 604

The trading posts established at the onset of the community are indicative of how the industrial base of the city would develop. Interest in the area as a port dates to 1828 when Mexican authorities considered the prospect but ultimately did not develop the area. Corpus Christi relies heavily on its port for trade and commerce such as with oil refining and the production of petroleum-based products. Oil is supplied from well fields in south and west Texas.[xxv]

Perhaps the most significant development in ocean bound trade were improvements made to the natural port to create a deep-water port for the city. The project included breakwaters provided by state funding and deepening of the ship channel as provided by federal funding. Government support was achieved through a hard-fought battle to persuade the Army Corps of Engineers to approve the port project.

The push included years of persistent lobbying by civic leaders such as manager of the King Ranch Robert J. Kleberg (1853-1932), and Henry Pomeroy “Roy” Miller (1883-1946) Mayor of Corpus Christi (1913-1919), among others. To complete this project, local voters overwhelming approved tax bonds to provide the local funding portion as a necessary match to the federal appropriation. Port improvements were completed on September 14, 1926.[xxvi] The Port of Corpus Christi as a formal entity was formed that same year and has grown to become the third largest port in the nation based on total revenue tonnage. Civic leaders originally envisioned the Port of Corpus Christi to be largely used for agricultural products. However, oil production in the state has led the port to largely focus on input and output capacity for this industry. In the late 1900s, pipeline infrastructure development brought petroleum to the city for refinement.[xxvii]

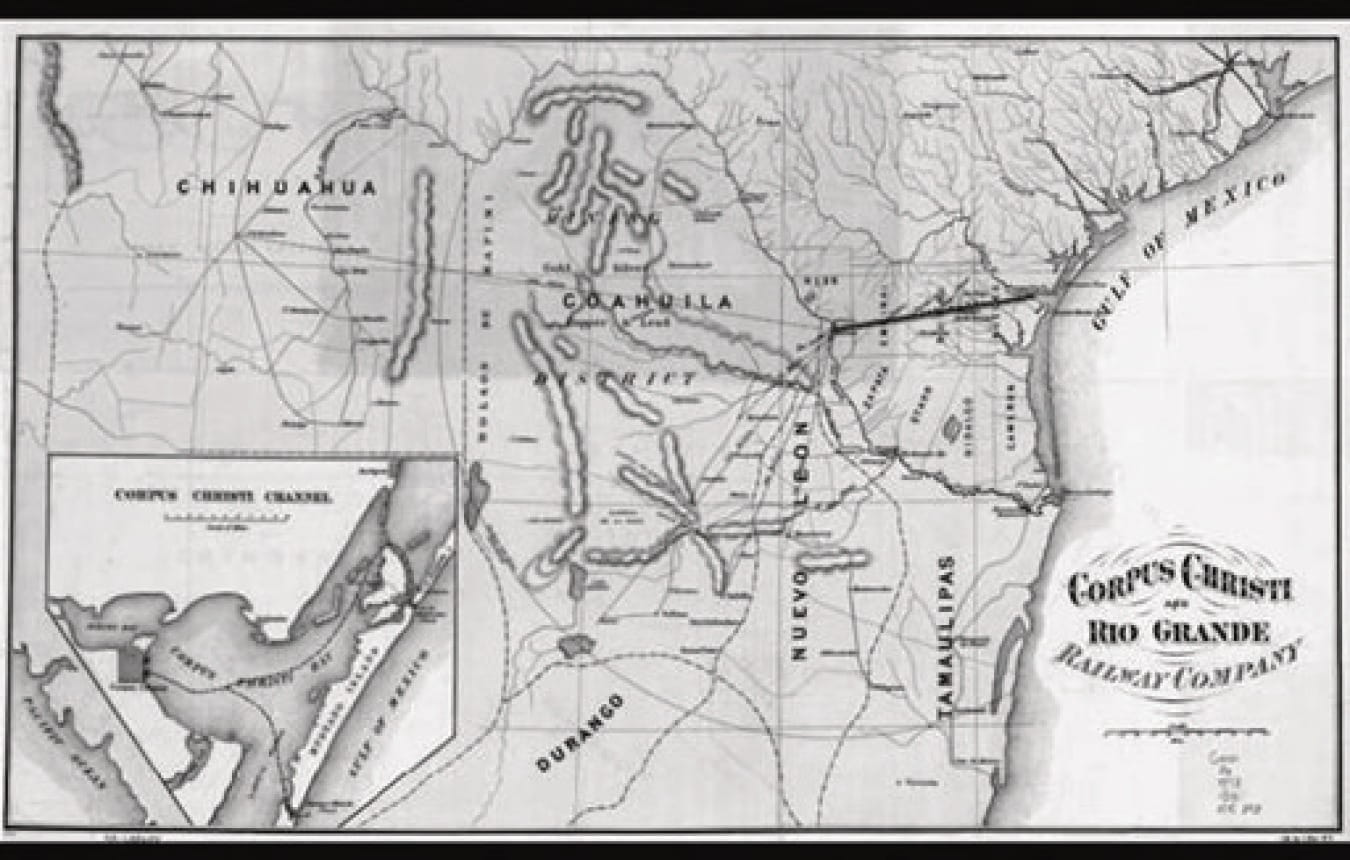

In the 1870s, railroads came to Corpus Christi as the city served as a main stop between San Antonio and the Rio Grande Valley. These rail lines were instrumental in supplying cattle from area ranches to Northern markets. By 1914, four rail lines served the city.[xxviii]

Corpus Christi and Rio Grande Railway Company, [Map of proposed railroad between Laredo and Corpus Christi and its connections with Mexico] (1873)

Bien, Julius (Contributor). Library of Congress, G4031.P3 1873.85

As home to several refineries and industries that produce oil-based products, Corpus Christi is an increasingly important logistics center for the oil industry. As U.S. petroleum production increased and due to a change in federal regulations in late 2015 to allow the export of crude oil, Corpus Christi became the largest crude oil export hub in the nation.[xxix][xxx]

Mexican American War

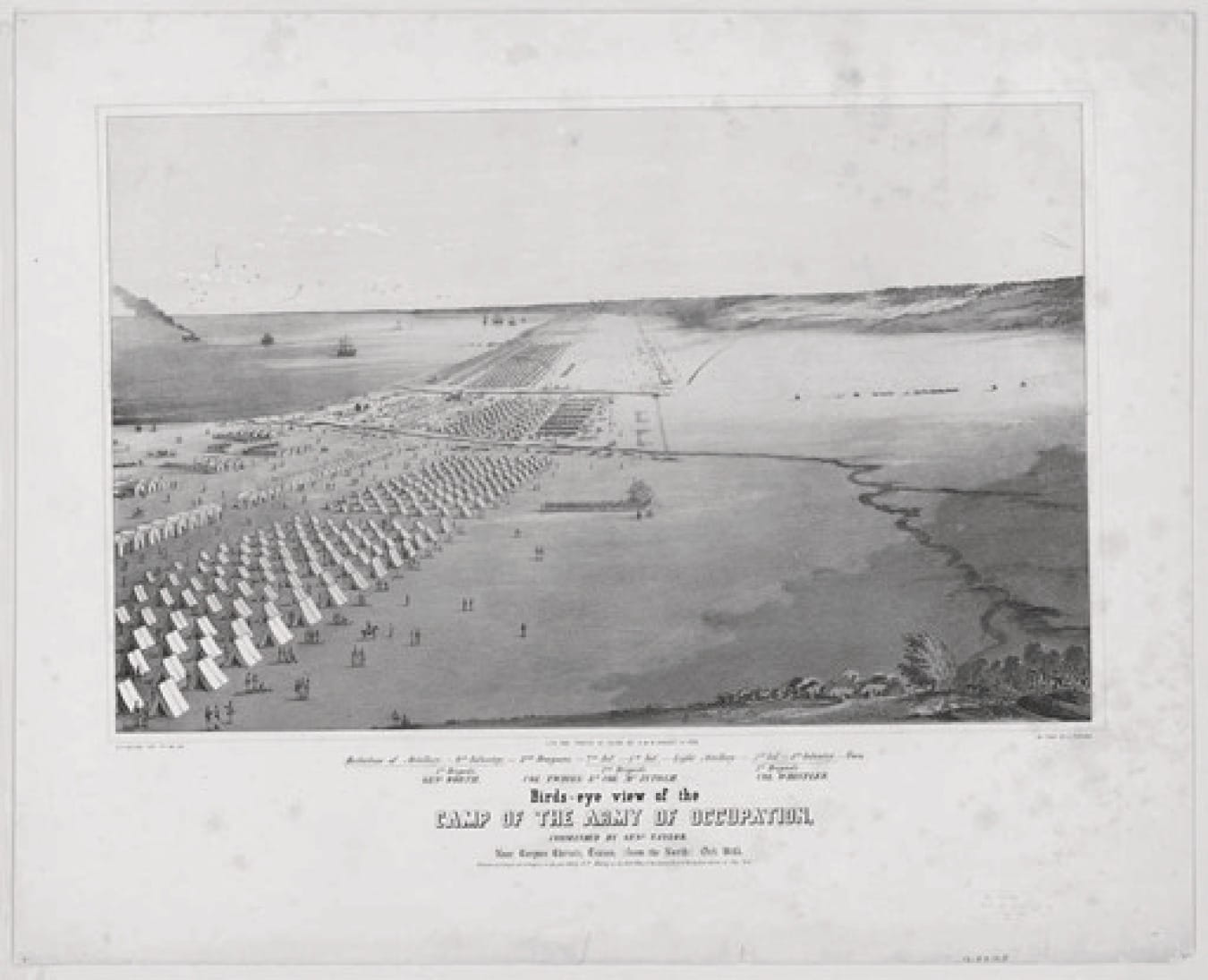

The proximity near the border and attachment to the Gulf of Mexico has led Corpus Christi to have a strong and enduring military presence. Several branches of the military have played a historically important role and remain an integral part of the region today. The U.S. military’s ties with Corpus Christi began as soon as Texas became the 38th U.S. State. In 1845, General Zachary Taylor encamped with 3,500 troops in the area in preparation for the Mexican American War. The declaration of war would not occur until April 25, 1846 but disputes leading to the conflict were gestating much earlier and culminated as Texas gained its statehood.[xxxi][xxxii]

A major source of conflict was the boundary dispute between Mexico and the U.S. The Nueces River, which flows into Nueces Bay and the adjoining Corpus Christi Bay, was claimed by Mexico as the northern border of their territory. However, the newly annexed State of Texas and the U.S. countered that the more southerly Rio Grande River was the border between the two nations. Thus, hundreds of square miles between the two rivers, referred to as the “Trans-Nueces,” was disputed territory.[xxxiii] Even though the area was sparsely populated, the Mexican government strongly contested any claim that this area belonged to Texas.[xxxiv]

The settlement of Corpus Christi, with its strong ties to the Republic of Texas, served as partial justification for the U.S. claim to the Trans Nueces. Thus, the encampment of Taylor in Corpus Christi was both symbolic and strategic. After seven months of training and preparation, Taylor marched his army south towards Mexico signaling a start to the major combat phase of the war. In addition to Taylor, who would become the 12th U.S. President, many future Confederate and Union officers would spend most of a year in Corpus Christi preparing for this action. These included Ulysses S. Grant, then a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, who would become the Union Commander during the Civil War and later the 18th U.S. President. The departure of Taylor’s army left Corpus Christi almost deserted and ended the economic boon which the stationing of troops had brought to the city. However, the retirement of many U.S. veterans of the Mexican American War to Corpus Christi led to a resurgence following the war.[xxxv]

U.S. Army Encampment in Corpus Christi

Daniel P. Whiting (Library of Congress)

The Mexican American War ended in a decisive victory for the U.S. with Mexico suffering a substantial loss of military and civilian lives and territory. Ultimately, the U.S. Army under General Winfield Scott occupied the capital of Mexico City. The conflict formally ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848 in the Basilica of Guadalupe at Villa Hidalgo, Mexico. The treaty set the Rio Grande River, not the Nueces River, as the border between the U.S. and Mexico. Further, the treaty ceded a vast amount of Mexican territory to the U.S., resulting in the formation of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of several other states in exchange for a small payment. This treaty placed the Corpus Christi over 150 miles north of the Mexico-U.S. border.[xxxvi]

The Civil War

Smuggling had occurred around Corpus Christi since before the establishment of the Republic of Texas. The Confederate States of America would use the port for smuggling goods in defiance of the naval blockade imposed by U.S. (Union) forces during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Corpus Christi was bombarded in August 1862 with Confederate batteries exchanging fire with Union ships. Mustang Is-land was occupied by Union forces under General Nathaniel P. Banks in late 1863 during maneuvers designed to cut off the smuggling of goods. The Civil War and associated blockade would result in many people leaving Corpus Christi and mark a low point in the development of the city. The Civil War also marked the second time that the area had been shaped by military operations due to its geographic importance. The military would further shape the use of Ward Island, the mission of the university, and the larger Corpus Christi community in the middle of the 20th Century.[xxxvii][xxxviii]

Post-Civil War and the Interwar Period

Following the Civil War, military interest in the area would wane with a decades-long lull in activity. In the 75 years between the Civil War and World War II, development of Ward Island never fully materialized. Some interest in private development of the island existed, but no large-scale projects ever successfully took hold.[xxxix]

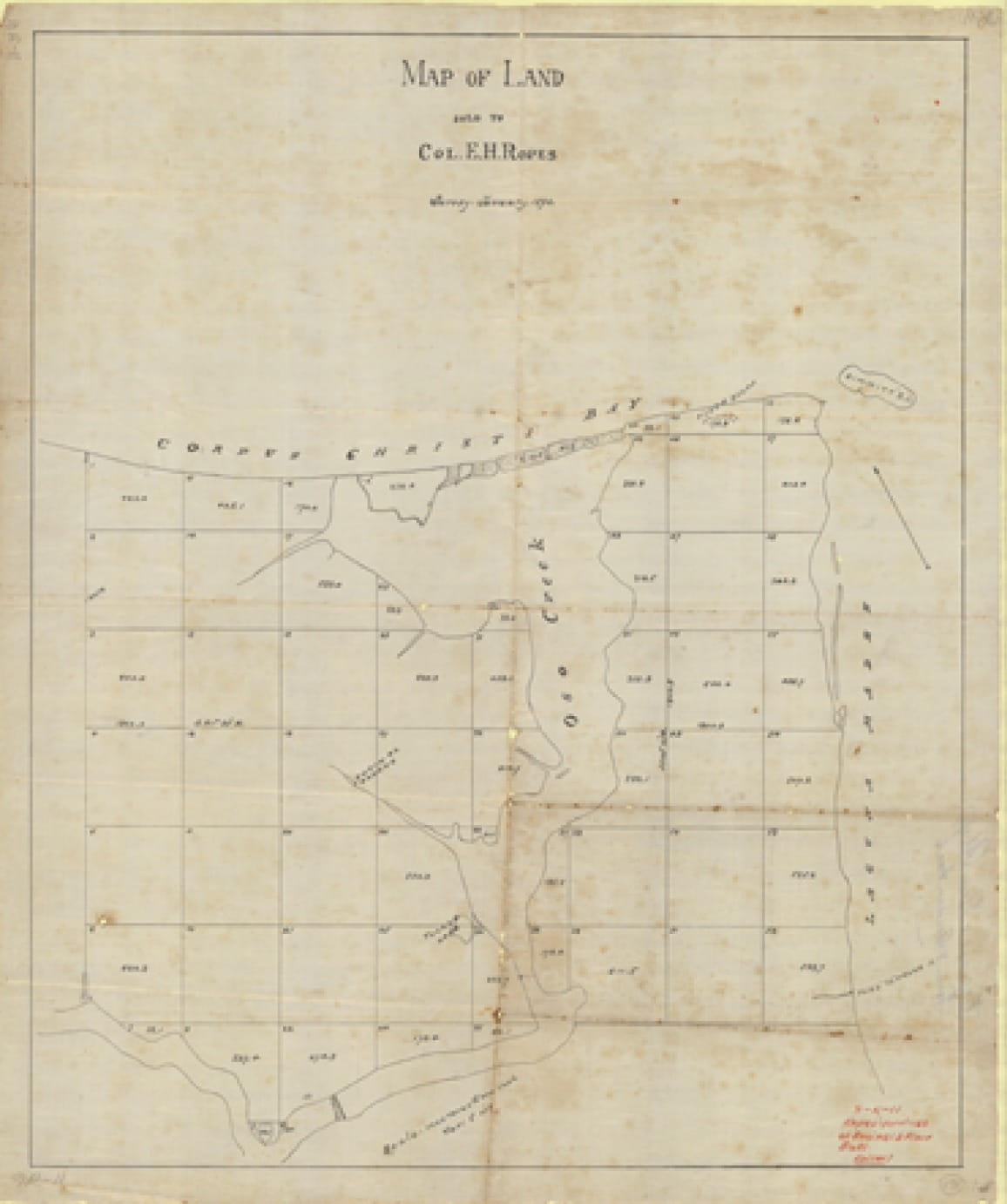

Map of Ropes Land Purchase (1911)

Charles H. F. von Blucher Family Papers, Collection 4, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Special Collections and Archives Department, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

In 1889, Elihu Harrison Ropes (1845-1898) of New York attempted to develop several projects in Corpus Christi including port improvements, rail line extensions, and industrial development. The basis for these developments would rest on the improvement of the natural port of Corpus Christi into a deep-water port. Thus, Ropes went about dredging a channel that would permit oceangoing vessels to sail the 32 miles from Corpus Christi Bay to Aransas Pass. His work set off a real estate frenzy known as the “Ropes Bubble.” Prices skyrocketed and the resulting economic bubble ultimately led to financial ruin for Ropes, his investors, and the Corpus Christi community.[xl] This work did lay an important foundation for later port improvements in the following decades. However, Ropes was not able to leverage his efforts into the industrial development he had envisioned.

Part of Ropes’ larger development plans included the property that would become Ward Island and surrounding land for a total of 1,280-acres. Ropes slated the island tract for residential real estate development.[xli] Rope’s entire project was abandoned after several setbacks and the onset of the Financial Panic of 1893. This led not only to failure of the development but largely contributed to the personal financial ruin of Ropes. He returned to New York having lost his entire investment and passed away destitute in 1898.[xlii] However, while Ropes was ultimately not successful in his development, his grandiose vision for Corpus Christi, as both an industrial center served by a deep-water port and a desirable sub-topical residential locale, served as a catalyst for others to work towards similar visions.

John C. Ward purchased the island in 1892 for the purpose of a real estate development consisting of an exclusive resort community. He paid $1,448 for the island and named it Ward Island after himself. He did not develop it due to an economic downturn and only remained in the area for less than two years.[xliii][xliv] Ward moved with his family to Beaumont, Texas after abandoning the project. Even though he did not fully develop the land or remain a resident for long, the island has retained his name which has persistently stuck even as ownership has changed and official action to re-name it has occurred.[xlv]

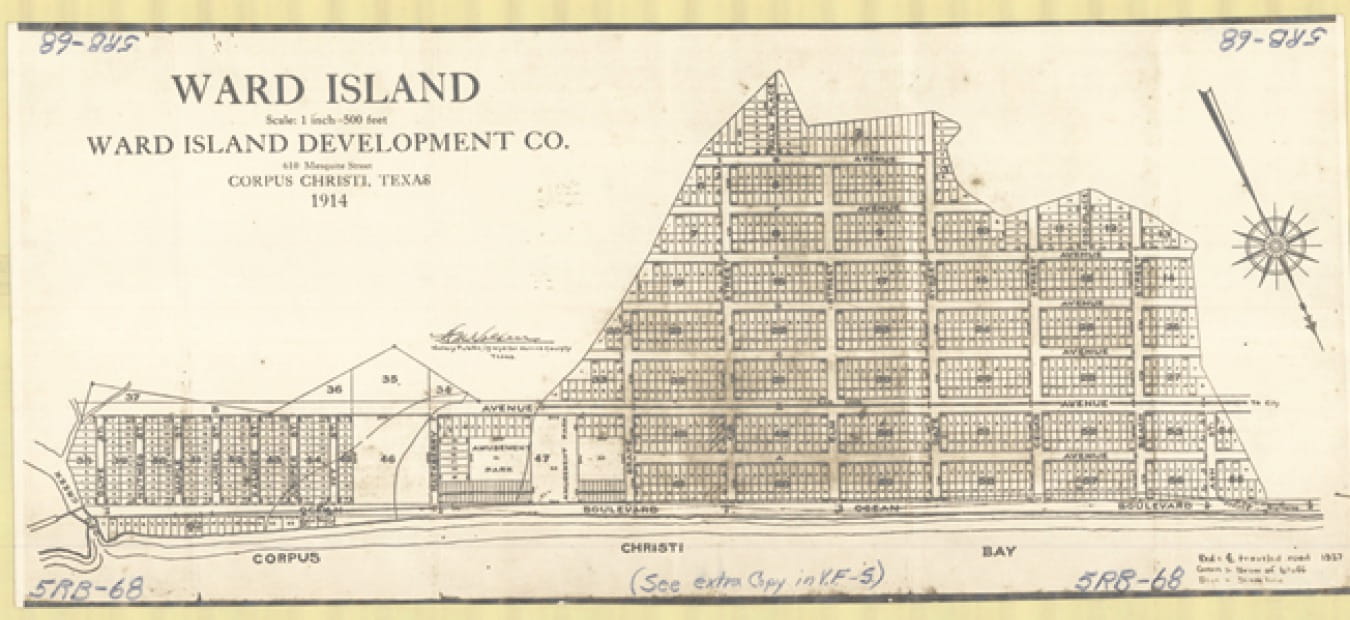

Development Plan for Ward Island (1914)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

In 1914, plans for an amusement park on Ward Island were made. There was to be an electric trolley line running eight miles from the town center to the Island. However, in 1916 a hurricane disrupted work and again the island was not developed.[xlvi]

After the failure of any large-scale development to take hold, Ward Island remained a destination for hunting and fishing for several decades.[xlvii] There is documentation that some families resided on the island and small-scale, tourism-related businesses were established.[xlviii] Cotton was farmed on about half of the island beginning in the 1920s. The first documented use of the island for aviation purposes was in 1924. The Elks-Kindred Flying Circus visited Corpus Christi and performed on Ward Island for thousands of spectators.[xlix] The following year, the Garver Flying Circus also performed on the island.[l] The flying circus featured not only the new technology of the day, the airplane, but acrobatics and stunts by performers. The selection of Ward Island for the circus emphasizes the lack of large-scale development of the property and also suggests that the island was accessible and notable in that thousands made their way to attend these performances.

A few small businesses, fishing piers, and a goat herd were present on the island leading into the 1940s when the military would take over the property.[li] The goat herd had been problematic for landing and taking off for the airplanes during the 1924 air circus performance.[lii] The goats would–sadly–be removed by the U.S. Army.

World War II

As World War II raged, the Roosevelt administration took action to increase the training facilities for U.S. Army pilots. To further this mission, a $25 million appropriation funded the Naval Air Station at Corpus Christi in 1940, and the base was commissioned in July 1942. Six stations related to the mission of naval training were located in South Texas including sites at Kingsville, Beeville, Flour Bluff, and south of Corpus Christi. These installations trained not only aviators but other key positions that would prove instrumental for building the U.S. Army Air Corps and ultimately winning the war. Advanced training was provided to service members of the Navy, Marines, Coast Guard, and the Royal Canadian Air Force.[liii]

Aviation Cadet at the Naval Air Base, Corpus Christi, Texas

Harlem, Howard R. Library of Congress, LC-USW36- 7056

The naval bases included Ward Island which would house a training facility called the Naval Air Technical Training Center Ward Island or the Radio Material School.[liv][lv] In 1942, the government took over the property and paid $143,406 for 23 parcels of land, thus consolidating all of Ward Island under government ownership for military use.[lvi]

Mrs. Imma Lee McElroy Paints the American Insignia on Airplane wings at the Naval Air Base, Corpus Christi, Texas (1942)

Library of Congress. LC-USW36-387

The school that was built on the island was a top-secret training facility for the newly implemented radar technology. While the installation was not to be discussed during the first years of its existence, a large military presence was established. Access to the base was strictly controlled, and the property was encircled by a security fence. Use of the word ‘radar’ by cadets who were training on Ward Island was an offense punishable by court-martial. Even the Marines guarding the facility did not know what was taking place inside. This level of secrecy highlights the importance of radar to the Allies during the war. The Ward Island facility was critical in this effort through training radar technicians.[lvii]

At the conclusion of the war, the base had 67 buildings including gymnasiums, dormitories, classrooms, swimming pools, storage facilities, and an administration building. Ultimately, 10,000 technicians would graduate from the Aviation Electronics Training School.[lviii][lix]

The winding down of military operations following World War II diminished the need for training facilities. The military no longer required the physical space that it had during the war and ultimately Ward Island was surplused for the purpose of a university. The radio station and the 2,300 students still based at Ward Island were moved to Millington, Tennessee, near Memphis, in September 1947.[lx][lxi]

“Sailor and Girl” (Corpus Christi, 1943)

Vachon, John. Library of Congress LC-USW3-033949-D [P&P]

While Ward Island was to change from naval control to serve as a university, the adjacent Naval Air Station Corpus Christi (NAS Corpus Christi) remained a military installation. This base lies to the east of Ward Island in the Flour Bluff area of Corpus Christi. Access via Ocean Drive between Ward Island and the naval installation is restricted and a security gate prohibits unauthorized traffic onto the base. Some operations of the base have changed over time, yet the core mission of training pilots has been consistent since its founding in 1941.[lxii] U.S. Army maintenance operations began on the base in 1961 as the Navy had shut down a major repair facility on the station two years earlier.[lxiii]

Enlisted Service Members Arrive in Corpus Christi, Bay (1972)

Dr Hector P Garcia Papers, Collection 5, Box 432, Folder 5. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

In 2021, a robust military presence is stationed at NAS Corpus Christi. In addition to U.S. Navy aviator training, the Army, Marine Corps, Customs and Border Protection Service, and Coast Guard all have operations on the base. The army maintains much of its fleet of rotary wing aircraft at the facility while Customs and Border Patrol uses the base to operate Unmanned Aerial Systems for surveillance.[lxiv] The retired aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CVT-16), berthed in Corpus Christi Bay as a floating museum, is a fitting tribute to the era that led to the modern development of the military in the city.[lxv]

Ward Island, with its facilities built for the purpose of instruction and quarters, made a logical site for an institution of higher education. However, Ward Island was not the only facility among the South Texas naval bases to be de-commissioned. Three retired naval sites in South Texas would play a role in the development of the Island University.

The Island

Ward Island has been home to a university since 1947, beginning with the University of Corpus Christi (UCC). Through several name changes, the university has provided educational opportunities for tens of thousands of students. Perhaps the most unique feature about the university is its geography. Those with close ties to the university may tend to forget that the tranquil, calming, and peaceful surroundings inherent with the coastal setting are a pleasure that falls well outside of the norm. Not everyone gets to travel to an island to work as a faculty or staff member or attend classes as a student. Indeed, the university is the only one in the nation to occupy its own island.

Many universities are defining physical landmarks of their communities, as is the case for the largest Texas A&M University system institution in College Station. The Bryan/College Station area has built up around the university. Other system schools have developed and grown as integral parts of smaller cities as with Tarleton State University and Texas A&M University-Commerce. A more recent trend focuses on bringing educational opportunity to downtown in the cases of The University of North Texas-Dallas and the downtown campus of The University of Texas at San Antonio. In contrast, a feeling of detachment from the community can occur on the campuses of Texas A&M University-San Antonio or Texas A&M International University in Laredo. These campuses were more recently built on large tracts of land to accommodate for growth. The Island University has physical restrictions imposed by the surrounding bays and estuaries as well as height restrictions due to flight training conducted at the nearby naval air station.

As with the Island University, campuses that are not immediately adjacent to their host communities may experience a sense of detachment from important stakeholders. The geography has made it at least more physically challenging to integrate into the larger Corpus Christi community. The campus has little commercial activity surrounding it to serve students, faculty, and staff. There are few stores, bars, or restaurants near the university that might serve as student “hangouts.” There is not the option to easily “go grab lunch” off campus in between classes by taking a short walk across the street. For instance, students attending The University of Texas at Austin often walk across Guadalupe Street to visit any number of restaurants and stores just across from the campus. As most students do not live on the island, they must journey to and from campus on Ocean Drive, the single route on and off the campus as road access to the adjacent military base is restricted. Even while there may be a physical distance, there is a strong community attachment. Without nearby commercial centers, students from the university tend to disperse into the community to work, volunteer, worship, shop, and reside. Islanders have become an integral part of the Corpus Christi community. Many students are from the area while many others choose to remain in the region after graduation.

The support of Corpus Christi and surrounding communities has been vital to the founding and development of TAMU-CC. The community was instrumental in attracting an upstart private Baptist college to Corpus Christi. Through several name changes and shifts in the mission of the institution, this support has remained steadfast and in certain cases critical for the very continuation of the institution.

Corpus Christi Bay at Ward Island (n.d.)

Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

[i] About Us. (2021). Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi https://www.tamucc.edu/about/

[ii] Howard, R. (1947, March 30). New Beeville College Dean experienced school builder. Corpus Christi Caller, p. 17.

[iii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[iv] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[v] Naval Air Station Corpus Christi. (2020, August 22). Commander, Navy Installations Command https://www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrse/installations/nas_cor-pus_christi.html

[vi] O’Rear, M. J. (2009). Storm over the Bay: The people of Corpus Christi and their port. College Station: Texas A&M University

[vii] Long, (n.d.). Corpus Christi, TX. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/hand book/ online/articles/hdc03

[viii] Lipscomb, C. A. (n.d.). Karankawa Indians. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaon org/ handbook/online/articles/bmk0 5

[ix] Karankawa Indians. (2020, August 29). Calhoun County Museum. https://calhouncountymuseum.org/exhibits/karankawa-indi-ans/

[x] Lipscomb, A. (n.d.). Karankawa Indians. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/bmk05

[xi] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xii] Wolff, (1969). The Karankawa Indians: Their conflict with the White man in Texas. Ethnohistory. Duke University Press.

[xiii] Karankawa Indians. (2020, August 29). Calhoun County Mu-https://calhouncountymuseum.org/exhibits/karankawa-indi-ans/

[xiv] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xv] Wolff, (1969). The Karankawa Indians: Their conflict with the White man in Texas. Ethnohistory. Duke University Press.

[xvi] Lipscomb, C. A. (n.d.). Karankawa Indians. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaon.org/handbook/online/articles/bmk0S

[xvii] Karankawa (2020, August 29). Calhoun County Museum. https://calhouncountymuseum.org/exhibits/karankawa-indians/

[xviii] Gatschet, Albert S. The Karankawa Indians, The Coast People of Texas., book, 1891; Cambridge, Massachusetts. (https://texashis-tory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth29754/: accessed October 14, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Star of the Republic Museum.

[xix] Camp Karankawa. (2020, August 29). Boy Scouts of America Bay Area http://www.bacbsa.org/camp-karankawa/69179

[xx] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxi] Long, C. (n.d.). Corpus Christi, TX. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdc03

[xxii] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxiii] Long, C. (n.d.). Corpus Christi, TX. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdc03

[xxiv] Hickman, G. C. (1995). A field guide to Ward Island, Corpus Christi, College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University.

[xxv] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxvi] O’Rear, M. (2009). Storm over the Bay: The people of Corpus Christi and their port. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

[xxvii] The Energy Port of the Americas. (2020, September 5). Port of Corpus Christi. https://portofcc.com/we-are-the-energy-port-of-the-americas/

[xxviii] Long, C. (n.d.). Corpus Christi, Handbook of Texas On-line. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/hand-book/online/articles/hdc03

[xxix] Chapa, S. (2019, June 11). Report: Port of Corpus Christi to become top S. crude oil export hub. Houston Chronicle: https://www.chron.com/business/energy/article/Report-Port-of-Cor-pus-Christi-to-become-top-U-S-13968069.php

[xxx] Long, (n.d.). Corpus Christi, TX. Handbook of Texas On-line. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdc03

[xxxi] Long, C. (n.d.). Corpus Christi, TX. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdc03

[xxxii] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxxiii] Library of The Changing Mexican-U.S. Border. https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2015/12/the-changing-mexico-u-s-border/

[xxxiv] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxxv] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxxvi] Library of Congress. The Changing Mexican-U.S. https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2015/12/the-changing-mexico-u-s-bor-der/

[xxxvii] Leatherwood, A. (2010, June 15). Naval Air Station, Cor pus Christi. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbn01

[xxxviii] Givens, M., & Moloney, J. (2011). Corpus Christi: A history. Corpus Christi, TX: Nueces Press.

[xxxix] Hickman, C. (1995). A field guide to Ward Island, Cor pus Christi, Texas. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University.

[xl] Givens, M. (2013, February 6). What was the big secret on John Ward’s island? Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[xli] Nueces County (2020). Elihu Harrison Ropes. Nueces County Historical Commission. https://www.nuecesco.com/countyservices/county-boards/historical-commission/elihu-harrison-ropes

[xlii] Nueces County (2020). Elihu Harrison Ropes. Nueces County Historical Commission. https://www.nuecesco.com/countyservices/county-boards/historical-commission/elihu-harrison-ropes

[xliii] Ward Island is no more; name changed. (1953, May 28). Corpus Christi Caller, p. 47.

[xliv] Givens, M. (2013, February 6). What was the big secret on John Ward’s island? Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[xlv] Givens, M. (2013, February 6). What was the big secret on John Ward’s island? Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[xlvi] Givens, M. (2013, February 6). What was the big secret on John Ward’s island? Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[xlvii] Hickman, G. C. (1995). A field guide to Ward Island, Corpus Christi, Texas. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University.

[xlviii] Warranty deeds filed for record. (1930, October 17). Corpus Christi Caller and Daily Herald, p. 12.

[xlix] Elks-Kindred Flying Circus at Ward Island. (1924, October 27). Corpus Christi Caller and Daily Herald, p. 1.

[l] Garver Flying Circus. (1925, March 29). Corpus Christi Caller and Daily Herald. Corpus Christi, Texas.

[li] Hickman, G. C. (1995). A field guide to Ward Island, Corpus Christi, Texas. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University.

[lii] Elks-Kindred Flying Circus at Ward Island. (1924, October 27). Corpus Christi Caller and Daily Herald, p. 1.

[liii] Delaney, N. C. (2013, May). Corpus Christi’s ‘University of the Air’. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/navalhistory-magazine/2013/may/corpus-christis-university-air

[liv] Hickman, G. C. (1995). A field guide to Ward Island, Corpus Christi, Texas. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University.

[lv] Leatherwood, A. (2010, June 15). Naval Air Station, Corpus Christi. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbn01

[lvi] Givens, M. (2013, February 6). What was the big secret on John Ward’s island? Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[lvii] Delaney, N. C. (2013, May). Corpus Christi’s ‘University of the Air’. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/navalhistory-magazine/2013/may/corpus-christis-university-air

[lviii] Hickman, G. C. (1995). A field guide to Ward Island, Corpus Christi, Texas. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University.

[lix] Rosser,]. (1978, October 12). CCSU worker must move after years on campus. Corpus Christi Caller, p. 66.

[lx] Branning, C. (1989, January 12). Baptist opened university. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. 67.

[lxi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxii] Naval Air Station Corpus Christi. (2020, August 22). Commander, Navy Installations Command Notification. https://www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrse/installations/nas_cor-pus_christi.html

[lxiii] Leatherwood, A. (2010,June 15). Naval Air Station, Corpus Christi. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbn01

[lxiv]Naval Air Station Corpus Christi. (2020, August 22). Commander, Navy Installations Command Notification. https://www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrse/installations/nas_cor-pus_christi.html

[lxv] Delaney, N. C. (2013, May). Corpus Christi’s ‘University of the Air’. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/navalhistory-magazine/2013/may/corpus-christis-university-air