6 Chapter II

Building a University

Aerial View of Ward Island (1948)

Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Special Collections and Archives Department, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Plans for what would decades later become Texas A&M University Corpus Christi (TAMU-CC) began in earnest in the mid-1940s. The original plans hardly resemble the university as it stands today. The name, location, and key stakeholders associated with TAMU-CC were different. The type of students to be served, as envisioned by early university founders, might now be considered only a slice of the large and diverse student body that now calls TAMU-CC home. Over decades, the Island University has been re-shaped, often due to pressures well beyond its control. However, the fundamental mission to provide South Texas with access to an educational institution remains true from the earliest discussions about starting a college through today.

U.S. Emergence

World War II defined a generation and transformed the U.S. into a global superpower. Through the period leading up to the war, the U.S. had a small military. There was little necessity for a standing army on the European model. The need to defend the U.S. border was minimal as its neighbors were allies and also had small militaries. The U.S. was only a minor player in terms of imperial expansion unlike Great Britain, France, Italy, Spain, and other European nations with their numerous overseas territories. For instance, at its zenith, the British Empire controlled a vast territory on which the “sun never set” as it covered a quarter of the World’s landmass. However, the U.S. was a sleeping giant in terms of industrial capacity. The nation’s large population would prove critical for building the armies necessary to fight a global conflict. Following World War II, a reordering of world powers would catapult the U.S. to the forefront of global affairs and commerce.

The war brought about significant social changes in the U.S. After the war, conditions were right for a historic expansion of higher education. Many of the common occurrences of life had been placed on hold as the U.S. engaged in the singular national mission of winning the war. Millions of young Americans had been called into uniformed service while millions more toiled to build the instruments of war not only for U.S. soldiers, sailors, and marines but also for U.S. allies. Great Britain relied heavily on U.S. goods to continue the fight in Europe against Germany and its ally, Italy. The U.S. had been supplying food and war material to Great Britain under the lend/lease agreement even before the U.S. was attacked at Pearl Harbor and entered the war in late 1941. A monumental effort to build everything from Liberty Ships for transporting goods to ammunition, tanks, jeeps, and aircraft shifted U.S. industrial capacity towards filling these enormous demands. U.S. consumers found limited availability of products ranging from butter to automobiles, as goods were either diverted for war time use or factories converted from making consumer products to war material.

After the war, returning soldiers were eager to gain an education to build their careers and provide for their families. The idealistic middle-class family–which lived in the suburbs, had an American-made car in the drive, and enjoyed many modern conveniences–began to take shape. In order to live this dream, the post-war generation needed jobs built on knowledge learned through higher education.

Millions of post-war marriages and a subsequent increase in births led to the term “baby boomers.” This term would describe a generation of post-war American children who were born into a much different world than before the war. Women, with a newfound independence in part due to wide-spread wartime employment outside the home, were beginning to enroll in college in record numbers.

As U.S. firms reverted production to consumer goods, they found global demand to be very high. During the war years, people had not been able to buy appliances, cars, or obtain a new set of tires. Once the war ended, groceries and fuel for cars were no longer rationed. Americans were able to spend freely, and they did. The pent-up demand, coupled with disposable income available to the bourgeoning middle class, led to strong sales of a wide range of products. Sales included many items that were new additions to most households such as small appliances and importantly the television, which represented an entirely new medium of communication. Americans took their cars to drive-ins and on road trips for vacation.

The U.S. had learned from mistakes made following the Great War (World War I) when soldiers were released back into the workforce with little provision to assist with this often-difficult transition. The abrupt dismissal of troops and lack of assistance for finding jobs or to pursue training had proved to be a major public policy blunder. After World War II, national leaders were determined to provide for a better transition back to civilian life for veterans. Service members were released more gradually from military ranks and benefits to assist with transition were provided. One way this was accomplished was by providing major financial support to help millions of service members attend college through the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (G.I. Bill). This program was constituted to pay the cost of earning a degree for those who had served at least 90 days in uniform.[i] These factors attributed to a high demand for college level educational programs. Thus, during this period many governmental and nonprofit entities were engaged in helping to fill this need through the founding and expansion of trade schools, colleges, and universities across the U.S.

Founding a University

The Baptist General Convention of Texas (BGCT) had been significantly involved in the higher education landscape in Texas prior to World War II. A forerunner of the BGCT, the Union Baptist Association, had established Baylor University in 1845 with approval from the Congress of the Republic of Texas. Baylor was originally located in Independence, Texas moving to Waco in 1885 in part due to the city’s access to a railroad line. Baylor would become the largest and most notable BGCT-affiliated university in Texas.[ii]

The BGCT also established Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Howard Payne University in Brownwood, Wayland Baptist University in Plainview, East Texas Baptist University in Marshall, and the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor in Belton. Each of these universities were founded decades before World War II. With the increased demand for higher education, BGCT members saw an opportunity to expand the footprint of faith-based education across Texas. None of the existing Baptist institutions were in South Texas. Beyond filing this regional void, many BGCT members felt that a presence in South Texas could draw students from Houston and San Antonio. The BGCT saw multiple benefits to this type of expansion including to their ministry. Baptist educational institutions not only provided higher education, but they also served to educate future ministers, and the institutions themselves served as a ministry for young people during the formative years of their lives. These institutions were viewed not only as universities but as missions that promoted religious instruction and the Baptist faith.[iii]

Beyond funding provided to veterans to gain education through the G.I. Bill, the government took steps to ensure that an adequate number of institutions existed to provide education. An incentive for creating a new university was to repurpose former military bases for educational use. Hundreds of military bases around the nation had been quickly built as part of the massive war effort. The bases were attractive to the BGCT and other entities as the government was trying to relinquish the properties and therefore offered financially attractive lease terms. The military did impose strict terms over the use of the buildings and land, as they wanted to preserve the right to reclaim the property and facilities should a need arise. South Texas had several surplused facilities as it had been an aviation training center with several fields and bases scattered around the region. Many of these were made available to local governments and other entities soon after the war.

One proposal was to repurpose Chase Field just east of Beeville, Texas as the site for a new Baptist University. Early advocates for this plan were primarily clergy from the Beeville area and Houston, 200 miles to the northeast. The strongest advocate for these plans was Rev. Aubria Allen Sanders, Sr., the pastor of the First Baptist Church of Beeville. Sanders recognized that a BGCT-affiliated college in Beeville could advance the mission to bring a Baptist institution of higher education to South Texas. He further recognized that the closing of the Naval Air Station at Chase Field would be a sizable economic loss for the Beeville community that might be partly offset by the founding of a university.[iv][v]

Beeville was a small city northwest of Corpus Christi and southeast of San Antonio. Sanders strongly advocated for Chase Field to be the home of the newly proposed college. Events moved quickly as during the spring of 1947 Sanders took a leave of absence as pastor to devote himself full-time to founding the college. Sanders was not only the visionary behind the school but also its first capital campaign chairperson and college board secretary.[vi][vii]

Rev. Aubria Sanders

1949 Silver King Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Special Collections and Archives Department, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

Wallace Bassett, the BGCT Board President, tasked Rev. Dr. S. Hutcherson and Rev. Dr. E. Hermond Westmoreland with determining the feasibility of a new Baptist university in South Texas. Both men were pastors of churches in Houston, Texas. Westmoreland was the pastor of South Main Street Baptist Church while Hutcherson was pastor of Trinity Baptist Church. There was no consensus between the two on where to locate the college as a major concern was that the Chase Field site was too large for a start-up college. However, the BGCT would ultimately approve the Chase Field location and further determined that the university should be a new school, not a branch of one of the existing Baptist colleges as had been discussed.[viii]

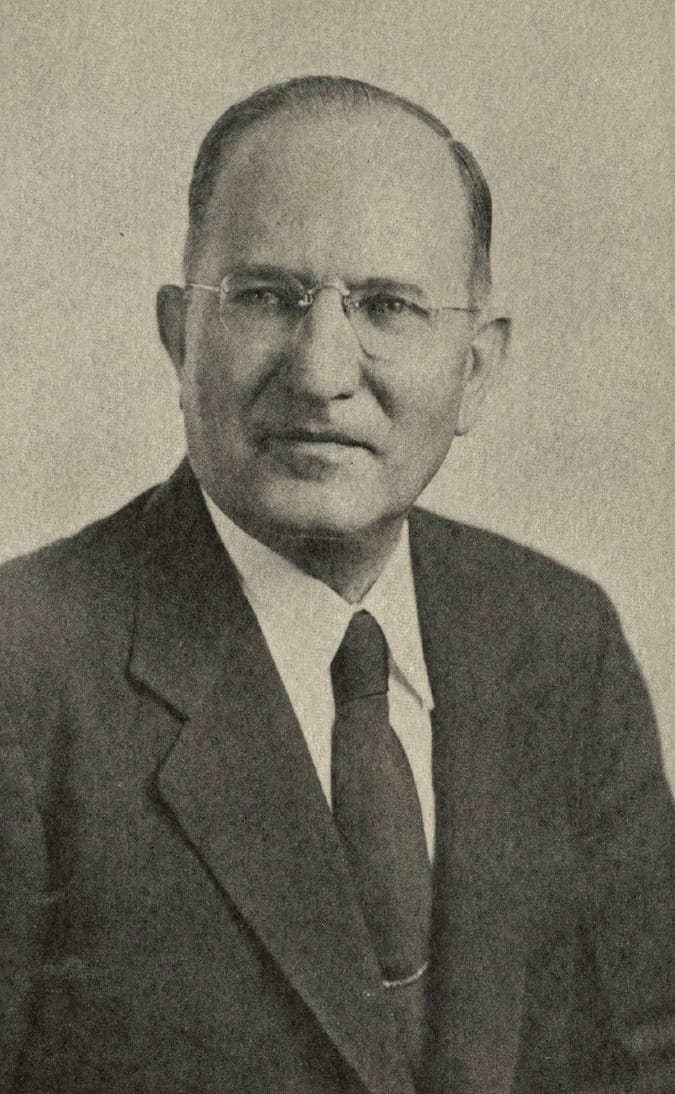

The ATC Board of Directors was filled mostly by ministers with few having extensive experience in higher education. Hutcherson was selected as the first president of the university and resigned his post as pastor at Trinity Baptist Church. Raymond M. Cavness was selected as the first academic Dean of the College. He was in the minority among early college leaders for having worked directly in higher education as both a faculty member and administrator. However, Cavness was given a leave of absence in June 1947, mere months into the job, as the demands of his position would not allow him to work to complete his graduate degree. Chairman of the Religious Studies Department John Cobb would become acting dean. Cavness would ultimately resign in September 1948. Hutcherson would only serve as president through the first academic year, leaving the post in 1948.[ix]

University of Corpus Christi President Rev. E.S. Hutcherson

1949 Silver King. Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Special Collections and Archives Department, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Arts and Technology College

Arts and Technology College (ATC) was formed with a decidedly Baptist underpinning. Contrary to what the name might have suggested, degrees focused on the ministry would be an important offering of the new college. Attendance at weekly chapel, as well as student behavioral expectations helped to define the college experience for students at all BGCT universities including ATC.[x]

UCC Students Attending Chapel (Circa 1950s)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Chase Field was one of six naval airfield installations built in South Texas at the start of World War II.[xi] The location was challenging as the base was somewhat physically disconnected from the city. Students and faculty who lived on campus would have to make the short drive into Beeville for any services that did not exist on site. Chase Field did have many of the necessary buildings and facilities for a college to start operations in a short amount of time. Among the 104 buildings were dormitories, dining halls, recreational facilities, and an administration building.[xii]

The ATC name was never intended to be permanent. It was adopted somewhat hastily with the intention of determining a more appropriate name later. Indeed, the name itself invokes a bit of an identity crisis. The other universities supported by the BGCT were decidedly liberal arts colleges with large numbers of ministerial students. The “technology” portion of the ATC name was ill-defined in terms of the mission and was more a reflection of the desire to utilize the available facilities at Chase Field than a goal of the BGCT. The naval air station at Chase Field had the necessary land and facilities to offer several technology focused degrees. For instance, the 2,600 plus acre site[xiii] would have ample space to develop a farm to provide agriculture students with on-site training. However, most backers from BGCT were more concerned about advancing its core mission as a Baptist ministry than offering industry centered degrees.[xiv]

The technology and career-based programs were outside of the typical scope of a Baptist-supported school as religion and bible classes were popular. Early course offerings at ATC were to include art, bacteriology, Bible, biology, liberal arts, journalism, Greek, and zoology among others. Over time, the focus of the curriculum would shift to more career-oriented coursework and degrees such as teacher education and business became increasingly popular majors.[xv] The divide between the BGCT mission and student demand for career-focused degrees would prove an ongoing source of internal conflict.

The early obstacles faced by ATC were formidable. The schedule for founding the institution and starting classes was remarkably quick. Perhaps more troubling was that the City of Beeville was not as supportive of the project to the extent that many in the BGCT had hoped.[xvi] The BGCT expected financial support from the community, local churches, and businesses at a level that never materialized. A clause in the contract between the City of Beeville and ATC, which allowed the city to cancel the lease with 90-days notice, provided little stability and the potential for a major loss of the BGCT’s investment. This clause was viewed by the BGCT as particularly unreasonable since semesters would run for longer than a three-month time frame.[xvii]

A sentiment grew that the city was just looking for another entity to assume the massive undertaking of maintaining the scores of structures and enormous track that had been Chase Field. These maintenance costs would place a heavy burden on ATC as the acreage and number of buildings far exceeded their short-term needs. The naval buildings had largely been constructed out of wood and for use as temporary structures to last the duration of the war. Thus, even buildings that were less than ten years old needed painting and significant repairs.[xviii][xix]

A difficult arrangement existed between the U.S. Navy (the owner of the property), the City of Beeville (the lease holder), and the board of directors of ATC (the tenant). Under the governance structure, the BGCT was involved as the sponsor and major financial backer of ATC. This unwieldy organizational structure was necessary to follow federal law that prohibited a religious entity from being granted surplused government property. Instead, a local government entity would act as an intermediary while the college, as a tenant, was to carry out the educational mission as desired by the U.S. Government for its decommissioned bases. Further, clauses in the contract allowed for reactivation of the properties for military use in the event of war or other need. Thus, not only could the City of Beeville exercise control over the property, so could the U.S. Government.[xx]

A major turning point for the future of the new university was rooted in tragedy when Rev. Sanders was killed in a car accident in May of 1947 mere months before the opening of ATC was set to occur in September. The accident occurred when Sanders was returning to Beeville from Houston on a fundraising trip for ATC. The untimely loss of Sanders, who was 44, was not only a difficult loss for the community, but it marked a turning point in deliberations over the location for ATC. Even as plans were made to memorialize Sanders by naming the library at Chase Field after him, the ATC location became increasingly problematic.[xxi]

Knowledge that the ATC board was disenchanted with the situation at Chase Field and looking for other potential sites to locate the school became commonly known in the summer of 1947. Further, articles suggest that within the Beeville business community there was little desire for ATC to locate at Chase Field.[xxii] In response, leaders from other communities in Central and South Texas began working to attract ATC to their own cities. Corpus Christi offered the ATC board an attractive proposal that included potential sites for locating at one of two former naval bases. The proposal pledged private and city funding to assist with the major financial outlay necessary to found a new university. The Corpus Christi offer was the most generous and the decision was made on July 25, 1947 by the ATC board to relocate there. The BGCT executive committee ratified the action in early August and students, who were slated to begin classes the following month, were notified of the change of location in a letter dated August 9th.[xxiii]

For a brief time, the university was referred to as ATC-CC (Corpus Christi), but the move quickly led to a name change from ATC to the University of Corpus Christi (UCC) for the opening of classes in fall 1947. The name was reflective not only of the new location but the standing as a four-year university with a mission to provide for a broad range of degree options beyond those of a more limited liberal arts college.[xxiv]

University of Corpus Christi Cheer Leaders with Anchor (n.d.)

Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

The University of Corpus Christi

The Corpus Christi community was supportive of bringing a university to the city from the beginning of the process. In relation to Beeville, Corpus Christi had a much larger population of 57,301 in the city limits and 115,000 in the area at the time. The region had a large industrial base and growing business community.[xxv] As a center of commerce, Corpus Christi was better positioned to raise the necessary capital and support needed for founding a private institution. Supporters such as Guy Warren and Howard E. Butt, Sr. were early advocates for building the campus in Corpus Christi. The two families are notable as long-time advocates and supporters of UCC.[xxvi]

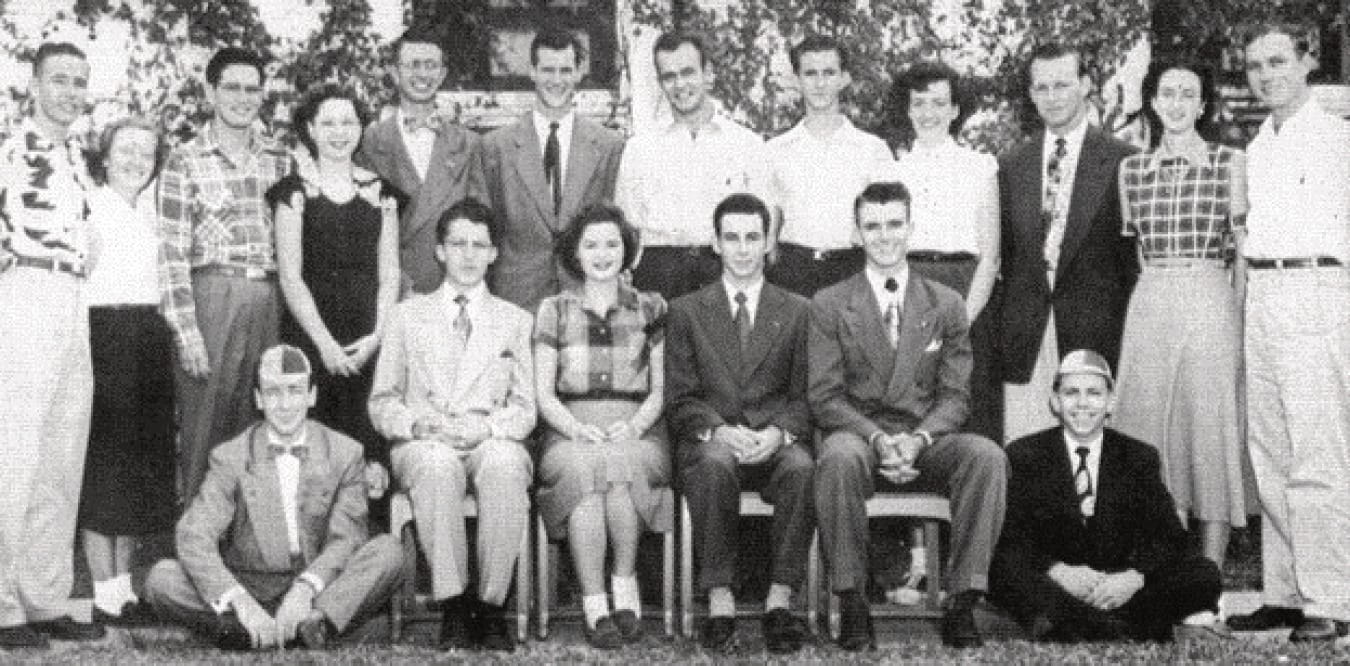

UCC 1949 Best All Around Girl, Hugh Delle Manahan and Best All Around Boy, Sonny Norrell

1949 Silver King. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Howard E. Butt, Sr. (1895-1991) was the CEO of H-E B Grocery Store. He generously supported UCC with both his business knowledge and financial backing. Butt would serve as Chairman of the UCC Board from 1950-1966. Several important financial gifts came from the H. E. Butt Foundation for which he was the founder. His son, Howard E. Butt, Jr. (1927-2016), would also be instrumental in the development of the school. He was a strong advocate of the promotion of Christian education in Corpus Christi.[xxvii] The Warrens were local oil operators. Guy Warren would serve as president of the Corpus Christi Citizens Council which pledged to raise $250,000 to establish a permanent location for UCC.[xxviii] Warren also served on the UCC board during its final years from 1972-1974.[xxix]

While the education of ministers remained an important function of UCC, the civic leaders who were investing in the school knew the community needed programs in business and teacher preparation in addition to a liberal arts curriculum. These more career-oriented programs would prove popular with students. Further, these demands would lead to low enrollments of ministerial students as a percentage of the overall student body. The percentage of ministerial students was a key bench mark that the BGCT set for each of its sponsored universities. The rather conflicting understanding of the mission would at times create friction among the various UCC stakeholders.

University of Corpus Christi Students (Circa 1950)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

In late summer of 1947, the campus was hastily moved from Chase Field to Cuddihy Field in Corpus Christi. Classes were never held at Chase Field even as investments had been made to ready the campus for students and faculty. The BGCT absorbed the losses associated with the renovations done at the base.[xxx] Just a few years later, Chase Field would be reactivated by the Navy during the Korean conflict to train jet fighter pilots. After permanent deactivation in 1993, the former Naval Air Station Chase Field property would be used for several purposes as part of the Chase Field Industrial Complex.[xxxi] Within this complex, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice occupies 304 acres for two correctional transfer facilities-West Garza and East Garza as well as the Department’s regional office.[xxxii] An industrial park and a small residential development also occupy portions of the former air field. In an interesting development, the Lone Star UAS Center of Excellence & Innovation (LSUASC) of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi operates at the site. The 8,000-foot runway, warehouses, and open area are used for testing and evaluation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS).[xxxiii]

Newly hired faculty, administrators, and students were provided with just over a month’s notice to report to Cuddihy Field, located just west of Corpus Christi, for the beginning of classes. Cuddihy Field was built in 1941 and named for U.S. Naval Aviator Lt. George Thomas Cuddihy who died in a crash of a British Bristol Bulldog test plane on November 26, 1929. Cuddihy was a 1917 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and one of the top naval pilots afterWorldWar I. He assisted with the formation of the navy’s first fighting plane squadron. He set a seaplane world speed record in 1924 and record for flight speed in pursuit of ships in 1926. In 1927, he flew across the Andes Mountains in South America, a route Lt. James Doolittle had also flown the previous year. Also in 1927, he won the “pursuit ship race” flying at over 180 miles per hour. Cuddihy is buried in Arlington National Cemetery and was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.[xxxiv]

In the original pre-war plans, Cuddihy Field, Rodd Field, Cabaniss Field, and 29 other landing sites in the area would serve as auxiliary airfields for Corpus Christi Naval Air Station (NAS). As World War II called for additional aviators, fields at Kingsville and Waldron were added in 1942. Chase Fieldwould be the last addition to the U.S. Navy’s extensive training facilities in South Texas with construction beginning in early 1943.

These would be active training bases with thousands of airmen, sailors, and support staff mostly engaged in naval training activities. Over the course ofWorldWar II, over 30,000 pilots would receive flight training from NAS-Corpus Christi. At the conclusion ofWorldWar II, 2,000 service members would be stationed at Cuddihy Field, with a total of over 20,000 across all the Corpus Christi area naval facilities. In September 1945, the decision was made to continue naval operations at Cuddihy and Chase Fields in addition to the main naval air station through 1946.[xxxv]

Much of the reported news about these facilities was not over the core, and secretive, activities of the bases but rather the social life that resulted from having a large military presence in and around Corpus Christi. Boxing matches and bowling tournaments were organized among service members representing the region’s naval installations. Several marriage and birth announcements noted the location of residence as “Cuddihy Field.” Sports teams, such as baseball and basketball, from these stations would routinely play one another.Ward Island, the home of the radio training facility would also field a team in many of these leagues. By the end of the war, these sports leagues were well established with team names such as the Cuddihy Clippers and Ward Island TechTras. These teams would continue through 1947.[xxxvi]

Cuddihy Field (1947)

1948 Silver King. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Cuddihy Field was an 803-acre site used for basic and advanced flight training with four 5,000-foot runways, large hangars, and auxiliary buildings. The former airfield lies a few miles south of the present day Corpus Christi International Airport and 13-miles from downtown Corpus Christi by automobile.

Preparations for the former military station took place in the month leading to the official start of classes on September 15, 1947. Enrollment for the the first semester at UCC was 312 students, including 63 prospective preachers and 97 veterans, taught by 26 faculty.[xxxvii]

UCC Students Exercise on the Cuddihy Field Campus (1947)

1948 Silver King. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Faculty had already been hired for programs designed to be offered at the Chase Field campus. Some of these programs were perhaps better suited for Chase Field but were still offered after the move to Cuddihy Field. Perhaps the most puzzling was the agriculture program as there would no longer be space for a university farm at either of the two prospective Corpus Christi locations. The move also placed the school within 40 miles of Texas College of Arts&Industries in Kingsville (later Texas A&M University-Kingsville) which was better positioned to offer agriculture programs given its relationship with and proximity to the expansive King Ranch.[xxxviii] In 1954, UCC would receive a gift of 100 acres near Robstown from Mr. and Mrs. M. G. Perry for the purpose of agricultural training.[xxxix] The agricultural program was designed to improve agricultural practice as opposed to training teachers. In this way, the program deviated from many of the other more liberal arts, business, or education focused programs. University leaders touted the program as one that might prepare “young ministers to better understand the way of life of the people with whom they work.”[xl]

UCC students were involved in missionary work throughout South Texas and the state. Several UCC students and graduates would go on to begin or pastor existing churches. Examples include Charles Gaines in Banquete, Roby Goff in Lane City, JamesWest in Ebony Acres, and Jake Setser at College Point Church as a mission of First Baptist Church of Palacios. The UCC choir was also an ambassador for the university, performing at several venues across the state including the annual meeting of the BGCT. UCC students would assist in the construction of missions and churches.[xli]

In the first few years of operation, UCC courses were taught in multiple locations. A separate teaching site for a nursing program at Valley Baptist Hospital in Harlingen began in fall of 1947 under the direction of UCC. The program would ultimately not endure, closing in the spring of 1950. An evening school designed for professionals was conducted in leased space in Downtown Corpus Christi beginning in 1950. Course scheduling would allow a student to earn up to nine hours per semester while working full-time. Offerings also included non-credit instruction and were tailored for students who worked in the area.[xlii]

First Cohort of UCC Nursing Students of Valley Baptist Hospital 1948

1948 Silver King. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

As for Cuddihy Field, the City of Corpus Christi began leasing the site from the U.S. Navy in 1947 for use as a general aviation civilian airport. This airport would supplement the Cliff Maus Municipal Airport which had opened in 1928 which lacked sufficient hanger space. The site would allow the city to offer recreational activities for citizens while leasing other buildings for a variety of uses including housing and event space. Corpus Christi Junior College (re-named Del Mar College in 1948)[xliii] leased one of the swimming pools. A drive-in theater would open on August 30, 1947. During the semester that UCC occupied Cuddihy Field, these other activities continued. UCC utilized eight buildings with a lease that was understood by both parties to be temporary. With the many different activities and interests represented at the former base, it would have been a lively place to attend classes.[xliv]

In 1960, Corpus Christi International Airport would open not far from Cuddihy Field. General aviation from Cuddihy Field and commercial service from CliffMaus Municipal Airport would be moved to this newly constructed facility, ending flight service at both of the older airports. In 1970, the northern portion of Cliff Maus Municipal Airport, located on Airport Road, became the site of the Corpus Christi State School. This is one of 13 state operated facilities for intellectually challenged individuals in Texas. The southern portion of the site is mostly city-owned parkland and recreational areas.

Little evidence of Cuddihy Field remains today. The main runways are no longer discernable, and the site largely remains undeveloped, used for farming, or for small scale industrial activity. The fence surrounding the former military base is largely intact yet overgrown and runs along Old Brownsville Road south of Saratoga Boulevard (Highway 357) just outside the Corpus Christi city limits. A few of the old structures, such as the hangars, remain but are heavily decayed and no longer in use.

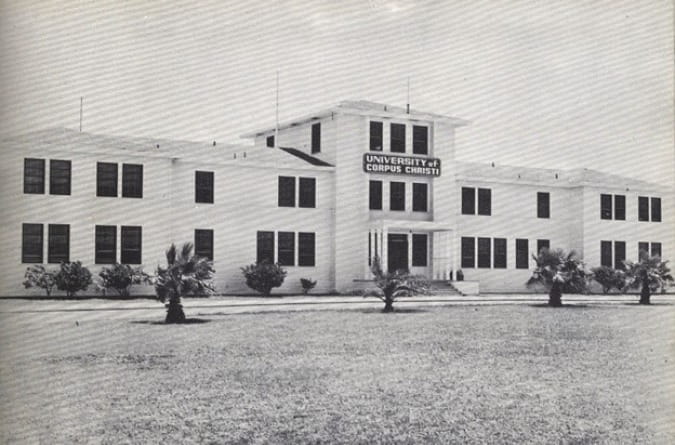

As classes began at Cuddihy Field, preparations for a more permanent site were being made. The 223-acre Ward Island would become the third and final site for UCC.[xlv] Serving as an intermediary, the City of Corpus Christi would provide a contract for a 20-year lease to UCC.[xlvi] As with Chase and Cuddihy Fields, Ward Island had former naval facilities that were suitable for on-campus residences, classroom space, and support services. A masonry building that had been the radio school’s administration building would serve the same purpose for UCC and be called by the nickname “the shingle.” There were two swimming pools which the Baptists would designate one for each gender and separate them by a fence to prevent the mixing of men and women. During a 1948 meeting, the UCC Ministerial Alliance student group discussed a motion to prohibit “mixed bathing” between genders in the pools. The fence remained until 1955.

Barracks were remodeled into student housing and faculty apartments. There were also dining facilities and a gymnasium. As with the other sites, many of these buildings were built hastily and intended only to be temporary structures. Early additions to the campus included an outdoor theatre and designation of a building as a music hall.[xlvii]

The interim years since naval occupation and the harsh climate had aged the structures. The cost of maintaining the property was high. Early reports to the Baptist General Convention of Texas indicate these costs, and the lack of outright ownership of the property, led UCC leaders to consider other potential sites in Corpus Christi after securing the Ward Island agreement.[xlviii]

First University of Corpus Christi Administration Building, Formerly Naval Administration Building (Circa 1948)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

UCC administrators also understood the need to make the campus more inviting as the utilitarian nature of a military base made for rather drab surroundings. However, the natural beauty and unique nature of the campus have always been notable. In a 1949 report to the BGCT, UCC leaders note “This is the only location, as far as we can learn, where a four-year college campus faces out directly on a beautiful bay, and the Gulf of Mexico.”[xlix] UCC would expend considerable resources on refurbishment and maintenance of the structures to ready them for a spring 1948 campus opening on Ward Island. As such, the move from Cuddihy Field would be completed over the winter break.[l]

The work to convert a former military base to a university campus would begin in earnest. More colorful and inviting paint schemes were introduced with much of the aesthetics being draw from its geographic location as an island. Additionally, the first library was named after Aubria A. Sanders and an oil portrait placed in the building in his honor.[li] Though the pre-war goat herd would unfortunately not return, through the 1950s around 200 hogs roamed the campus. These were raised and slaughtered to help feed UCC students.[lii]

Leadership

A Board of Trustees had authority over UCC. In 1948, the board had 24 members mostly from South Texas but with several being from Houston. Board members were to serve three-year terms. Mrs. Guy Warren and H. E. Butt Sr. were founding members who served for many years and became significant financial supporters of UCC.[liii]

UCC would ultimately have six presidents with Rev. Hutcherson serving as the first. While the reasons for his resignation are not directly stated, Hutcherson indicated in a letter to faculty that the difficulty in operating UCC and a lack of clarity in its mission perhaps contributed to his decision. These same issues would plague the UCC presidents who followed. Upon receiving Hutcherson’s resignation, the UCC board voted unanimously to request he reconsider–to no avail. The board was forced to find a new president for UCC’s second year.[liv]

In the interim, a committee of UCC administrators would run operations with John Cobb serving as Chairman of the Religion Department, acting Dean, and acting President. The committee formed to select a new president chose Cavness, who had resigned as Dean in 1947. He would begin his duties on September 8, 1948.[lv]

Raymond McCarey Cavness (1904-1975) was previously an assistant professor of Spanish at Southwest Texas State Teachers College and later President of San Marcos Baptist Academy. At this time, he was one of the youngest university presidents in the nation. He had also been an instructor and graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin earning a Master of Arts and PhD. Prior to his career in higher education, Cavness had been a public-school teacher and superintendent. Cavness served as a Lieutenant Commander on the staff of General Douglas McArthur during World War II and the subsequent military occupation of Japan.[lvi]

As UCC President Cavness was paid $8,000 per year and provided with on campus housing in the house formerly occupied by the station commander. Cavness would prove a capable administrator, but the financial situation of UCC made operations difficult. Cavness would resign in June 1951 to continue his studies at The University of Texas (Austin) and to attend to his health. His resignation would come as a shock to the UCC community.[lvii]

Cavness would become the sixth President of San Angelo College in 1954 where he led the transition of a two-year college into a four year institution named Angelo State University. Cavness dropped the “San” portion of the original name to ensure that in any alphabetical listing of Texas universities, the school would be at the top. He felt this could be an advantage when state legislators were looking over appropriations bills. Following a heart attack in 1965, he retired in 1967. Cavness died on April 11, 1975. The Science Building at ASU is named in his honor.[lviii][lix]

Following the departure of Cavness, Dean A. M. Witherington would serve as interim president for one year until a permanent appointment could be made. Witherington joined the institution in 1949 after serving as department chair and then Dean of Ouachita College in Arkadelphia, Arkansas for 15 years. His experience also included stints as a public school principal and superintendent in Tennessee and Kentucky. Witherington would resign as UCC Dean in 1953.[lx]

During this same period, the first talk of a merger occurred for the Island University. A proposal to merge another BGCT school, Mary Hardin-Baylor University, located in Belton, with UCC was discussed. At the time, the all-female, Mary Hardin-Baylor was experiencing steep declines in enrollment. Merger plans did not advance beyond these initial discussions yet efficiencies across the BGCT universities would be a consideration for decades.[lxi]

In April 1952, the board named Walter A. Miller to serve as president. Miller had served as superintendent of Odessa, Texas public schools and Dean of Odessa Junior College. He had studied at the University of North Texas, The University of Texas (Austin), and Columbia University. He would remain in the position for 13 years, the longest of any of the UCC presidents. Miller resigned to become superintendent of schools for Crane, Texas in fall of 1965 before retiring in 1972. Walter Miller Hall at UCC was dedicated in his name.[lxii][lxiii]

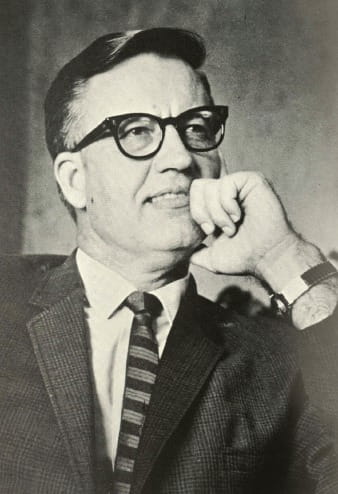

Dr. Joseph C. Clapp, Jr. would be named UCC president after serving as Vice-President of Development. In that role he had overseen fundraising, recruitment, and public relations building important relationships for UCC. Clapp held a B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. from New Orleans Theological Seminary. He was named interim president upon the departure of Miller.

W.A. Miller Hall (Men’s Dormitory) (n.d.)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Clapp would renew efforts to seek regional accreditation, trim the athletics program, begin a capital campaign, and push to increase faculty salaries to attract more qualified individuals. As Clapp took over as president, he noted that UCC was open to all students, not just Baptists or those who wanted to become ministers. Clapp would pass away during his tenure as president from a heart attack on January 10, 1968.[lxiv][lxv]

In August 1968, Leonard L. Holloway (1923-2003) would be named president. Holloway held a master’s degree from the University of Oklahoma and came to UCC after having served as vice president at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. He had also been a vice president for the H. E. Butt Foundation. His most recent position was at Mary Hardin-Baylor, a sister school of UCC.[lxvi][lxvii]

In contrast to Clapp’s statement that UCC was open to all, Holloway was disappointed in the high percentage of non-Baptist students at UCC. He hoped to further the ministerial mission of UCC by converting students to become Baptists and opened the Center for Applied Christianity as a research and study center. His presidency was particularly short, as he served only until the following January, or roughly one semester. Holloway would later serve as President of Mary Hardin-Baylor in Belton, a two term Mayor of Kerrville, Texas (1989-1992), and Executive Director of the Kerrville Chamber of Commerce. [lxviii][lxix]

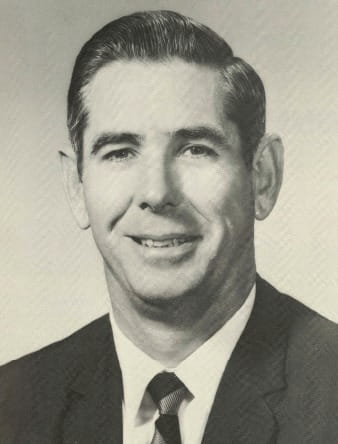

UCC President Leonard L. Holloway

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

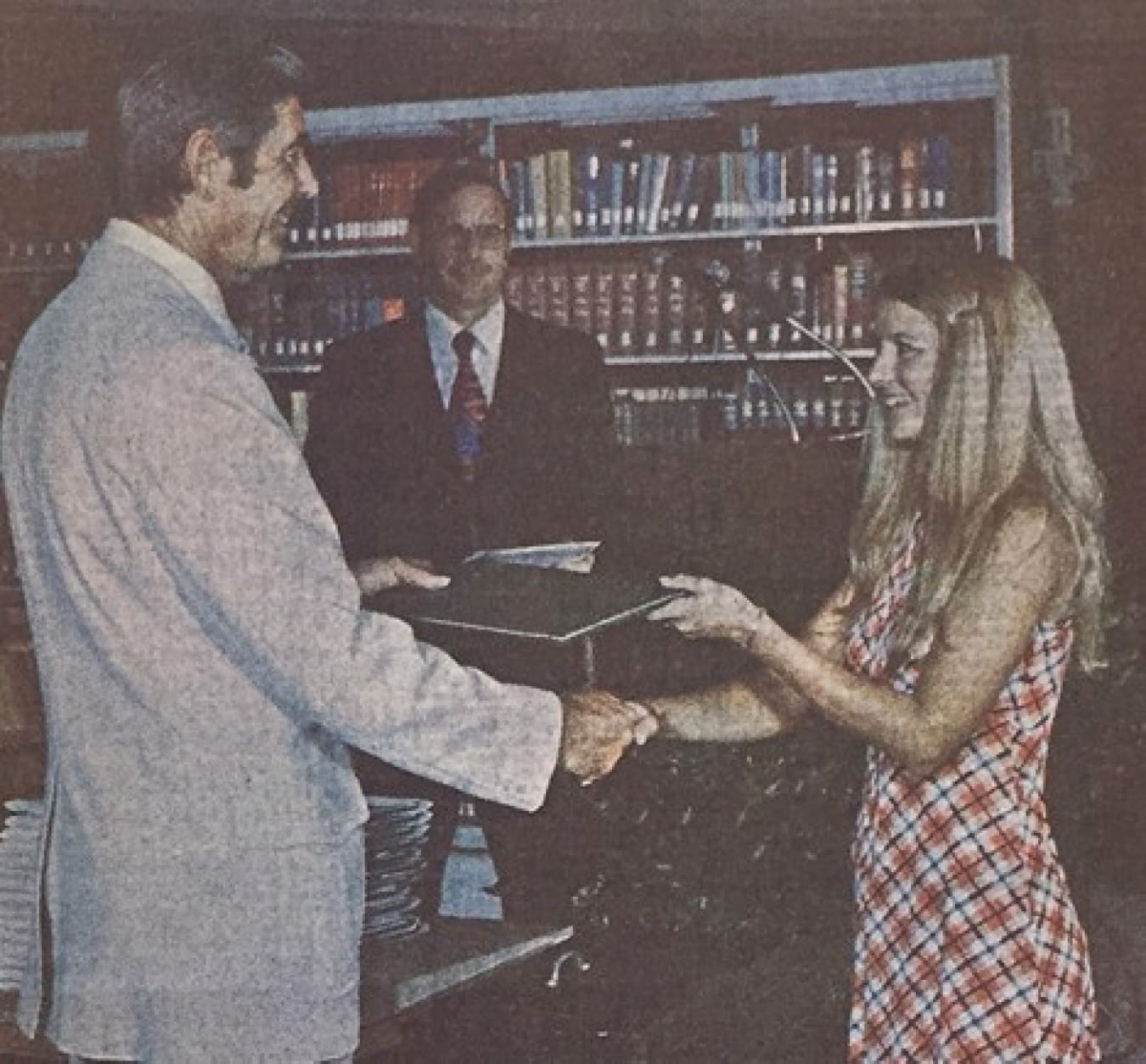

The last president of UCC was Kenneth A. Maroney (1929-2016). He was College Dean and had served as acting president for much of 1968 upon the death of President Clapp. He was again named interim president upon the resignation of Holloway and offered the position on a permanent basis in June 1969.

Maroney was a UCC alumnus who competed on the 1949-1950 basketball team before beginning a long career on the Island University. That year, the Tarpons Basketball team ended the season with an unequaled 25-1 record. Maroney was hired as an instructor and assistant basketball coach in 1957. As a coach, he helped shaped the lives of countless students with many considering him “like family.” He later served as Dean of Students and Professor of Psychology. Maroney earned an Ed.D. in Counseling and Professional Administration from North Texas State University in 1962.

Maroney would serve as president through the transition of UCC to a public institution and was given an honorary doctorate degree during UCC’s last spring commencement. Maroney would serve on the faculty of Corpus Christi State University until his retirement. He remained active as a supporter of the Tarpon Foundation, Alumni Association, and Islander athletics, being named to the Islander Athletic Hall of Honor in 2002.[lxx][lxxi][lxxii]

UCC President Kenneth A. Maroney

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Maroney’s brother, Robert (Bob) Maroney, was also a standout athlete, coach, and professor over the course of five decades at the Island University. On his retirement in 2007, Dr. Bob Maroney was named Professor Emeritus of the College of Education of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi by the Texas A&M University System.[lxxiii]

Challenges

A similarly disjointed arrangement for ownership of Ward Island existed as had existed as had been in place at Chase Field in Beeville. The City of Corpus Christi acted as an intermediary between the highly bureaucratic federal government, through the Department of the Navy, and UCC. However, the City of Corpus Christi proved more effective and willing to serve in this capacity than the City of Beeville had been in 1947.

The partnership led to a more productive, albeit still clunky, governance structure. However, UCC, with the help of the city, secured the purchase of Ward Island in 1951. The transfer of ownership required several approvals with most being from various military branches to ensure that the property was not needed for any military purpose in the foreseeable future. This process was slowed by the Korean conflict as the need for military installations again increased during this period. The purchase price for the property was $570,000 with half covered by the BGCT and half to be paid back to the BGCT through a long-term financial campaign undertaken by UCC.[lxxiv][lxxv][lxxvi]

Ownership of the property meant that the university could make extensive changes to the campus without gaining any approvals from the Department of the Navy. At the time of the deed transfer, there were 40 major buildings. Once UCC owned Ward Island, removal of exterior fencing and other structures formerly used by the military would give the campus a more inviting feel. Ownership also allowed for continued renovation and removal of aging naval buildings and infrastructure to occur. Facility maintenance often proved to be a costly undertaking given the poor condition of the infrastructure and the harsh coastal climate.[lxxvii]

Hurricane Carla caused significant damage to the campus when it struck in September 1961. The storm washed out the west entrance from Ocean Drive leaving students to enter through the south gate of the nearby Naval Air Station, drive through the installation, and arrive to campus through the east entrance. The storm led to a decline in student enrollment and contributed to a financial burden not only in lost revenue but due to costly campus reparations.[lxxviii]

From its founding, UCC sought to gain regional accreditation. This was important for students to be able to transfer their earned credits to other universities as well as to have their degrees carry a higher distinction for quality. In addressing the campus ownership issue, university leaders took the first of many necessary steps towards this goal.[lxxix] However, accreditation would prove a long and difficult undertaking.

Broadly speaking, accreditation concerns not only the governance and quality of academic programs but also the support students receive in other areas of the university as well. Impediments were present on numerous fronts. In the earliest years, many faculty members lacked the higher level of academic degree required for regional accreditation. Efforts to hire faculty with terminal degrees (e.g., Ph.D.) proved difficult. This issue was addressed over time but attracting faculty remained an ongoing challenge in part due to low salaries.[lxxx] UCC also preferred that faculty be Baptists or at least Protestant. In the 1961 report to the BGCT, President M. A. Miller noted that the percentage of faculty identifying as Baptists had been increased and “if a Baptist cannot be found for the position, the next step is to know they are Christian and members of an evangelical Protestant group” in his description of faculty recruitment efforts.[lxxxi]

The number of degree programs offered was often too great for the number of students enrolled at UCC. This situation led to concerns over the quality of instruction. Fifteen years after its founding, the university had programs in English, biology, chemistry, Bible, history, mathematics, Spanish, speech, education, music, art, sociology, French, physics, government, and geology.[lxxxii]

Accreditors assessed many of the old naval buildings to be substandard and subject to fire due to their wooden construction. This was a justifiable concern as a wooden structure building used for education classroom space caught fire in 1958 and was a complete loss. An additional concern was the ability of the structures to withstand the storms that were a regular occurrence on the bay front location. This point would also prove valid as a major hurricane would strike the campus in 1970 causing extensive damage to the wooden structures.[lxxxiii]

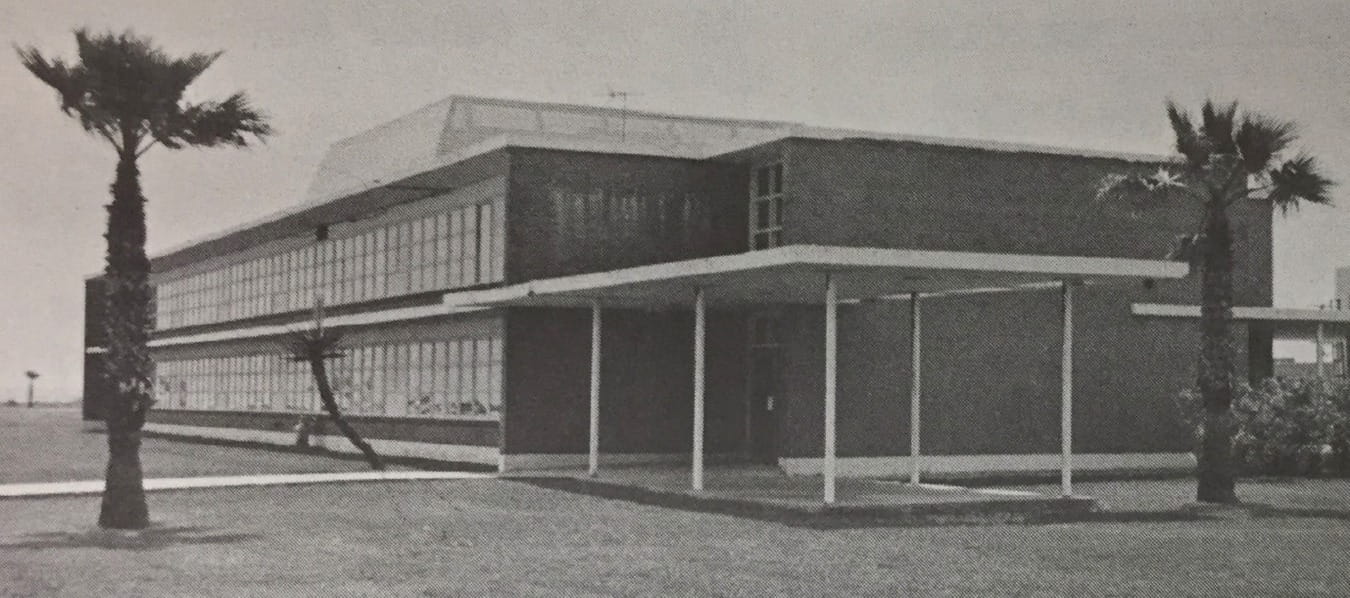

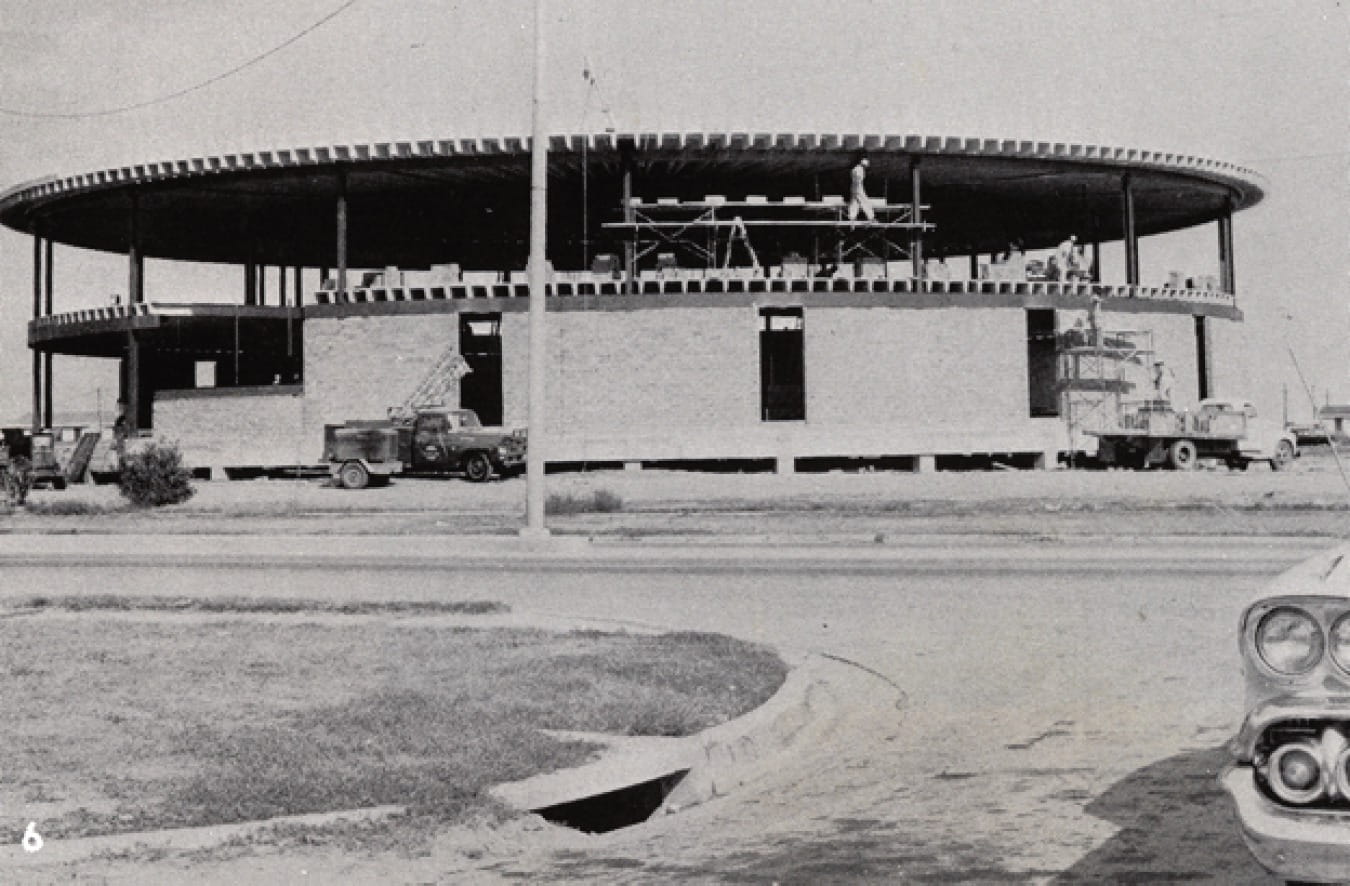

For many of the early years of UCC, the library had inadequate holdings to support the student body and academic programs. This issue was addressed with the addition of a new library building on campus in 1963.

This structure is still affectionately known as the “round building” and was a modern, state of the art building at the time of its construction. The 24,000-square-foot building cost $300,000 with space for 80,000 volumes. The new library was a gift of the Butt Foundation.[lxxxiv] Mary Elizabeth Holdsworth Butt (1903-1993) was instrumental in bringing this building to campus and supplementing the library’s collection.[lxxxv] She was a philanthropist and early backer of UCC along with her husband, Howard E. Butt, Sr.

The library holdings increased greatly from just over 13,000 in 1955 to 57,000 in 1969, helping address a deficiency that was hampering accreditation.[lxxxvi] As with the round building, many of the masonry buildings built by UCC remain in use today as most have been repurposed for other functions than originally constructed.[lxxxvii]

Construction of the University of Corpus Christi Library (Circa 1963)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

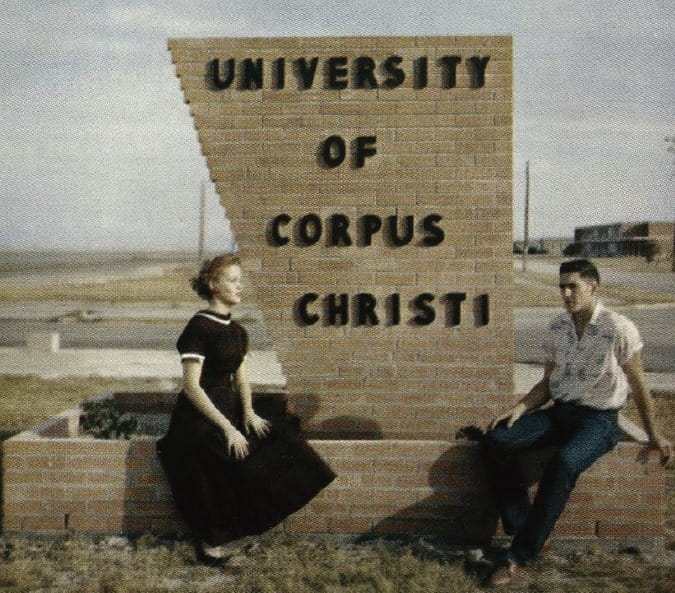

In the 1950s, UCC began to develop its own identity as it was no longer a tenant of the U.S. Navy. Ownership of the land and a desire for accreditation led university administrators to develop a master plan for the campus in 1952. One year later, the Nueces County Commissioners Court officially changed the name of Ward Island to University Heights to recognize the prominent place of UCC in the community. This change was requested by UCC officials.

Long-time Corpus Christi historian and columnist Murphy Givens noted the humor in this name as the island is “flat as a floor.” However, this official change did not take hold and use of the name Ward Island remains prevalent. In this same year, the long-standing tradition of giving buildings nautical themed names began.[lxxxviii][lxxxix][xc]

University of Corpus Christi Entrance sign (1947)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Construction of the university’s first brick building was begun in January 1955. The $150,000 structure was named after Gazzie Warren, an early supporter and board member of UCC. Warren Hall was 18,700 square feet and would accommodate 84 female students.[xci]

Residence Hall (Formerly Warren Hall) at CCSU (1979)

Alumni Update, June 1979. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

A new $100,000 administration building was completed in 1956. The building was constructed behind the Navy’s old administration building and consisted of a one-story, 8,200-square-foot air-conditioned building.[xcii] W. A. Miller Hall was built in 1957 as a dormitory to house 100 male students and still stands on the campus having been renamed “Classroom East.” The Science Building was built the following year and is now named “Classroom West.”

In 1967, the red brick Glasscock Memorial Student Union Building was dedicated. Mr. Charles Gus Glasscock (1895-1965)[xciii] served as an early board member of UCC and university supporter. The facility included a dining facility, chapel, and the UCC student center. The Glasscock Building is now home to the student success center. The small chapel remains part of the building to the present.

The Moody/Sustainers Field House was donated by the Moody Foundation and the Sustainer’s Club of Corpus Christi with each group contributing $100,000. Guy Warren led this fundraising effort for the Sustainers. [xciv]

Glasscock Student Success Center (2020)

Andrew Johnson

Classroom West (2020)

Andrew Johnson

In addition to the start of many construction projects and physical changes to the campus, programmatic changes occurred during this time as well. Teacher education has been a popular major since the earliest years of the Island University. Beginning in 1952, a kindergarten was started on the Island within the Division of Teacher Training.[xcv] The program was expanded to include additional grades and programs such as special education. At the time of implementation, the special education program for teacher training was the only specialized program in the State of Texas.

In 1954, a petroleum engineering school was established through contributions from companies in the energy industry to help supply the demand for engineers in the bourgeoning South Texas energy sector. Mr. Norman Lamont was recruited from Texas Technological College to lead this program.[xcvi][xcvii] The petroleum program would not be a lasting addition to the curriculum but would emphasize the breadth of offerings even at a time when enrollments would not support the number of degrees offered. UCC enrollment reached a high-water mark of 996 in 1967.[xcviii]

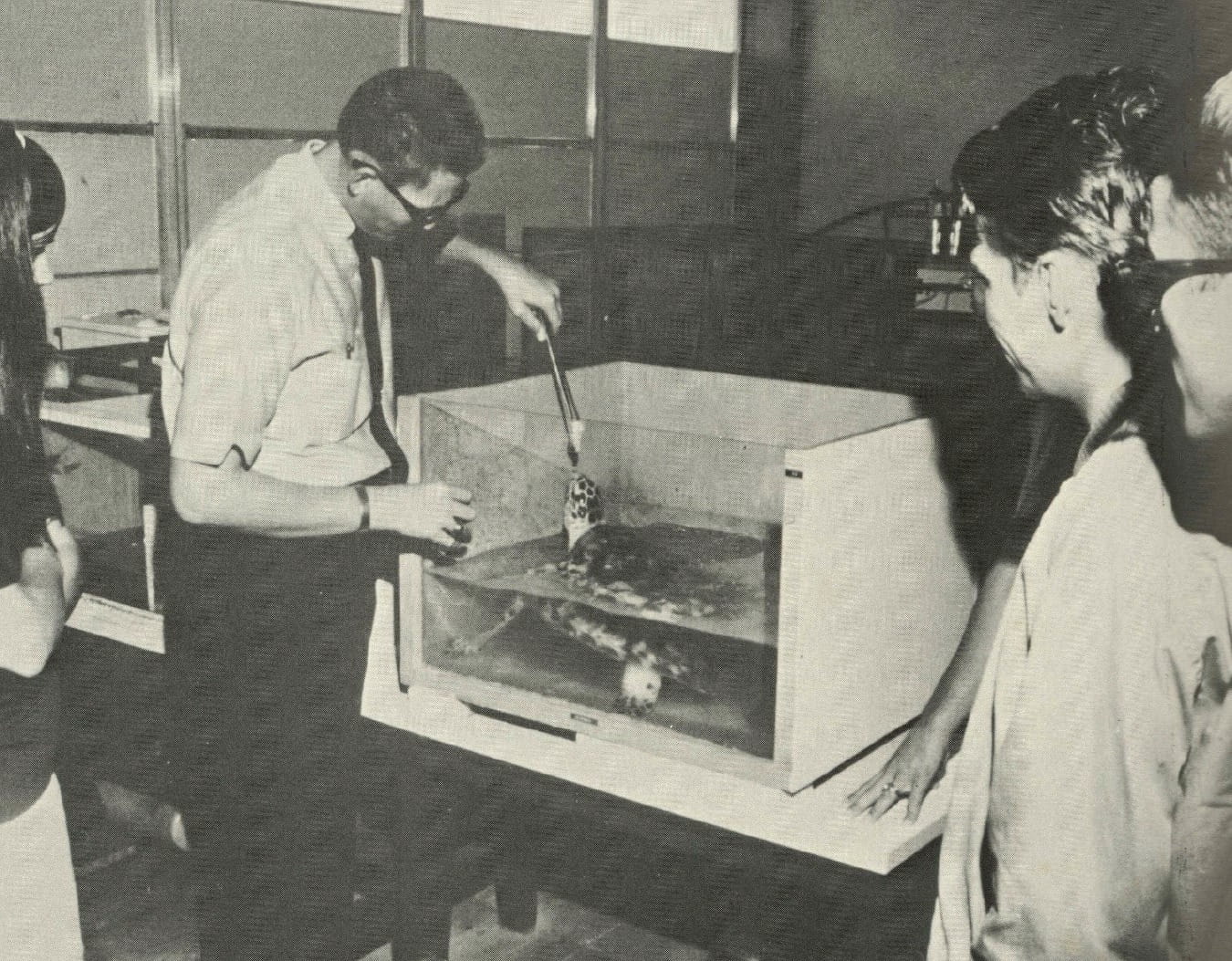

In 1957, the Department of Marine Sciences was added. This would mark the beginning of work in an area for which the Island University would become world-renowned. Early reports for the department note that research work was conducted on the Laguna Madre areas of Texas in support of fishing and sports industries.[xcix] The U.S. Geological Survey would open an office on Ward Island in partnership with UCC for the study of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean in 1969.[c]

Sea Turtle Feeding (n.d.)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Struggles

In 1961, UCC almost lost its Texas Education Agency (TEA) teacher certification accreditation. The TEA certification is separate from regional accreditation but critical as it is required for graduates to be able to obtain a teaching certification in Texas. Teacher education was a popular major, and the loss could have led to one-third of the student body not being able to pursue teacher certification upon completion of their degree. While UCC was able to appeal the decision and take steps to remedy the situation, the case highlighted the strain the university faced in its ability to deliver programs. This accreditation issue was but one aspect of the larger challenge that gaining regional accreditation posed for the entire university. UCC would gain full accreditation from the regional accreditation body in 1968, over 20 years after its founding.[ci]

Highly related to the struggle for accreditation were the ongoing financial strains UCC faced. While the BGCT provided an annual allocation to fund operations, it was far from enough. In 1966, it was noted that the cost of upkeep for the campus was an excessive portion of the budget.[cii] Further, BGCT supported ministerial students through scholarships. These funds were not a direct appropriation but instead covered tuition and fees for the student. In turn, the university had to provide the educational services for these students. Evidence suggests that the BGCT struggled to provide adequate funding for its nine universities. In 1955, an emergency five-year $12 million campaign was established to assist all BGCT universities.[ciii]

Some of these funds would be gained through church offerings. UCC consistently relied on fundraising and local supporters, particularly board members, to maintain operations. Indeed, bills were often past due and loans were necessary to complete several academic years. Tuition for a small private university was already expensive, leaving little ability to raise rates which would have simultaneously served to dissuade students from attending due to cost.[civ]

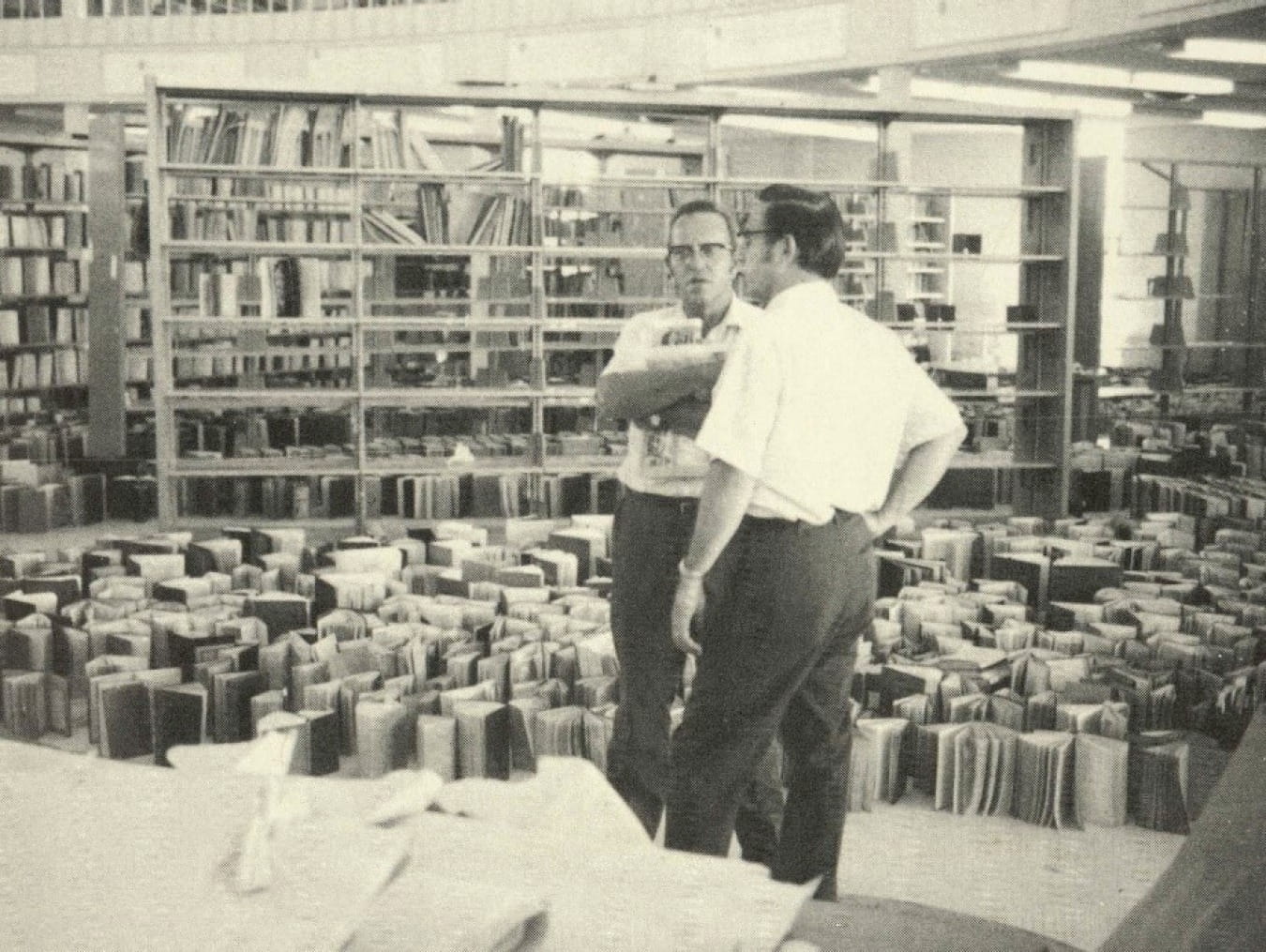

Many challenges highlighted through the accreditation process were not solved but rather limited. These challenges were exacerbated when Hurricane Celia struck Corpus Christi on August 3, 1970. The storm had winds up to 118 miles per hour with the center of the storm hitting nearby Port Aransas to the north of campus. The storm was one of the worst to hit Corpus Christi in recorded history. It was devastating in terms of property damage to the city and the UCC campus. UCC Dean Wrotenbery indicated virtually every roof on campus had damage, the library sustained considerable damage to its collection, and several of the naval buildings as well as the auditorium were a complete loss.[cv]

Damage to the UCC Library Caused by Hurricane Celia (1970)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Dr. Richard Marcum and Dr. Carl Wrotenbery Survey Damaged Books in the Library Following Hurricane Celia

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Damage Caused by Hurricane Celia to Campus Housing (1970)

Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Following Hurricane Celia, a disagreement over the funding of repairs to the campus between the BGCT, the UCC board, and campus administration ensued. Emergency funding was necessary to prepare the campus to open the following month for the fall 1970 semester. The main sticking point was the UCC board’s decision to use federal relief funds to make repairs as insurance payments were slow to materialize. [cvi]

The BGCT had been unwilling to provide any immediate financial assistance to UCC in the wake of the hurricane.[cvii] To fill the immediate need for funding, UCC had sought and received a $500,000 Small Business Administration loan as a line of credit while insurance claims were negotiated.[cviii][cix]

There was a strong sentiment that the use of this federal funding violated the separation of church and state which many BGCT delegates believed should have been respected without exception. Reporting in the Dallas Morning News framed the situation in stark terms stating “BCGT told the school to repay the loan with money borrowed from an agency other than the federal government or withdraw from the denomination.”[cx] Further, UCC supporter Howard E. Butt, Jr. held this same sentiment viewing the use of government funds as improper.[cxi]

The rift over how to finance the campus rebuilding was the latest in a succession of disappointments in the eyes of many BGCT members. UCC had never grown its enrollment to levels that the BGCT expected or that would enable the university to operate with financial security. Other BGCT-sponsored universities were increasing enrollments and, perhaps more importantly to members, had larger enrollments in ministerial education programs. Creating additional challenges to enrollment, the BGCT opened Dallas Baptist University and Houston Baptist University in the mid-1960s thus creating additional competition for prospective students.[cxii]

Gains in enrollment at UCC had been difficult to achieve by merely recruiting from South Texas. Recruitment efforts aimed at New York and Chicago had yielded the increased numbers that administrators desired but many of these students had no interest in studying for the ministry. Indeed, these students were typically from well-off families that could afford to pay the private school tuition. The students were much more interested in a liberal arts experience than starting churches or becoming members of the clergy.[cxiii]

Corpus Christi was supportive of UCC; however, the mission of UCC was sometimes at odds with the needs of the community. For instance, the BGCT required its board members to be Baptists, thus restricting many willing and capable leaders from the local community from serving in this capacity. Across the state, decreasing church membership, fewer churches being founded, and diminishing funds were leading the BGCT to re-evaluate its sponsorship of universities. The BGCT released control over Baylor Medical School in Houston in 1969 and in the following year released Baylor Dental School in Dallas.[cxiv]

The BGCT tracked the religious affiliation of students at its affiliated universities, and UCC consistently disappointed in this regard. The BGCT wanted a large percentage of the student body, and preferably the faculty, to be Baptist. Achieving the desired homogeneity in the student body was difficult in South Texas given the large number of Catholics in the area.[cxv]

Christopher College, a Catholic-supported institution, operated in Corpus Christi from 1957 to 1968. It was located on Saratoga Boulevard between Airline Road and South Staples Street.[cxvi] This institution was founded as Mary Immaculate Teacher Training Institute and changed its name to Christopher College in 1965 when reorganized as a junior college. While the college also struggled financially, during its rather brief existence the institution represented additional local competition for UCC.[cxvii]

Diverging interests in student recruitment was nothing new as these efforts had long been challenging for administrators and were ultimately disappointing for the BGCT. In the early days of UCC, the demand for education was very high given the post-war boom. Nearby schools, such as the Texas College of Arts & Industries (Kingsville), were experiencing record enrollments.[cxviii] The newness of UCC, its core focus on the ministry, and its higher cost of attendance likely pushed many prospective students to other universities. Later, the out of state recruitment efforts yielded few Baptists and ministerial students but rather diversified the religious affiliation found on campus and drove demand for majors other than religious studies. When enrollments did increase, it was more a result of this out of state influx than an increase in educational opportunity for the local population. The end of the World War II era G.I. Bill and the higher tuition rates at a private school made education at UCC less attainable, especially for people who are from lower socio-economic standing. The number of Hispanic students at UCC was very low relative to the demographics of the South Texas region. In 1950, university administration reported 35 Latin American students out of a total student population of 556. This year did mark the first year that international students would attend UCC with one student each from Mexico and Chile. By 1956, students from 13 foreign countries, 12 states, and 77 Texas counties were part of the student body. [cxix]

UCC’s challenges contributed to a push for a state sponsored university to be in Corpus Christi. Even in the early 1950s, state and local leaders recognized the limitations of UCC to fulfill the educational needs of the region. The cost of attendance and sense of exclusion for many due to its Baptist affiliation, made UCC a less desirable option for some South Texans. Additionally, there was a concern that many students could not afford to or would not travel far for their education. Efforts were sought to address this situation. A legislative proposal by Corpus Christi State Representative William H. Shireman in 1953 would have made Del Mar College in Corpus Christi into a four-year college along with two similarly situated junior colleges in the state. While the measure did not pass the Texas Legislature, the concerns over educational access in the region were present even in the early days of UCC.[cxx]

By the 1970s, Corpus Christi was the largest city in Texas without a state-sponsored senior level university as San Antonio had secured construction of a University of Texas affiliated campus in the late 1960s.[cxxi] The business community in Corpus Christi also recognized that economic development may be hampered by the lack of a comprehensive public institution. The Chamber of Commerce formed a committee to study the issue in late 1966.[cxxii] By 1968, the Coordinating Board of the Texas College and University System determined that an upper-level university was needed in Corpus Christi.[cxxiii] A citizens group led by John Crutchfield (1919-2011) also championed the cause.[cxxiv][cxxv] Crutchfield was an influential Corpus Christi businessman as an owner of a petroleum engineering consulting firm, Crutchfield & Pruett.[cxxvi][cxxvii]

During this same period, the BGCT was taking actions that would position UCC to become independent from the convention and thus able to be brought under control of the State of Texas. However, this was not a universally popular idea. Much of the final push towards independence on the part of the BGCT rested on the Carden Report which the convention had commissioned. Dr. William R. Carden, Jr., (1937-2018) a former administrator at Stetson University in Florida, was contracted and charged with studying the financial situation of all nine of the BGCT-affiliated universities. The report he submitted recommended that UCC be released from BGCT control effectively letting it work towards transfer to the state. The report also recommended that the BGCT close Howard Payne College and Wayland Baptist College. For the state’s part, there was also discussion at the time over the need for state-supported universities in these areas, similar to the situation in Corpus Christi. However, the state ultimately did not act in these other cases, and these schools were ultimately not closed. Howard Payne University and Wayland Baptist University remain affiliated with the BGCT.[cxxviii] Other recommendations dealing with organizational changes and finances were also made by Carden. The report concluded that half of the BGCT universities did not have sufficient library resources and recommended that some “non-Baptists” be allowed to serve on the UCC board. Ultimately, a committee of 12 BGCT members reviewed the report and recommended action on the items pertaining to UCC.

Carden would go on to work for his alma mater Baylor University, as a banker at several banks in Texas, and as founder of the Center for Banking and Financial Studies in the Baylor Business School in 1982. His professional life was capped by board membership of KFC Corporation and the financial company Q2. [cxxix][cxxx]

The Carden report and subsequent recommendations were not without controversy and were not embraced by some affiliated with UCC. President Holloway responded to a news story about the potential for UCC to separate from the BGCT by stating that he was not interested in the idea. Holloway would leave UCC in 1969 just as the recommendations of the Carden report were being considered. UCC Board Chairman Othal Brand of McAllen was more direct in his opposition to allowing UCC to become independent stating in early 1969, ”As long as I am a member of the board, it will be a Baptist school.”[cxxxi] Brand noted the recent progress made in increased enrollment and campus building projects. UCC had also been successful in obtaining full regional accreditation in 1967.[cxxxii]

In the end, many reasons contributed to perhaps an understanding or at least inevitability that the UCC model was not sustainable. The aftermath of Hurricane Celia accelerated the already diverging trajectories of the BGCT and UCC.

The Island University was to rebuild its mission and its physical campus from Hurricane Celia to become an upper-level public institution that would serve a more broad, diverse, and larger study body. UCC was an attractive candidate for acquisition by the state as opposed to creating a new public university from the ground up. UCC leaders knew the addition of a state university in Corpus Christi would have competed for students, likely further contributing to the ongoing enrollment and financial struggles. Actions by the UCC governing board worked to ensure that UCC transitioned to become a state-supported campus. On January 21, 1971, the UCC board acted to become independent of the BGCT while selecting Corpus Christi Mayor Jack R. Blackmon (1918-2006) as its Chairman[cxxxiii]. This move would underscore the increased reliance on the City of Corpus Christi and the community as partners of the university as support of the BGCT would fully diminish by 1973. The board would be instrumental during this transitional period.[cxxxiv]

The BGCT would end its affiliation with UCC with initial action on March 9, 1971 and adoption by a vote of all BGCT delegates in October of that year. A two-year transition period was implemented to allow many students to complete their studies and for an orderly conversion to state control.[cxxxv] UCC held its final commencement ceremony in summer of 1973. In 26 years, UCC graduated over 1,500 students and set the foundation for higher education on Ward Island and in the Coastal Bend region. The university that started as UCC would continue and grow during a new phase beginning in the fall of 1973.[cxxxvi]

President Dr Kenneth Maroney Award the Last UCC Degree to Susie Austin (Haisler) Also Pictured is UCC Dean Dr. Carl Wrotenbery

Original Photograph by George Tuley (1973) Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Christian Education Activities Corporation

An impediment felt by some BGCT members, community leader Charles H. Butt, Jr., and the Corpus Christi Baptist Association Mission Superintendent Dr. W. H. Colson was the abandonment of the religious mission of UCC should it become a state institution. Even through the financial struggles, educating ministers and its missionary work in South Texas were deeply important to these stakeholders. In the negotiations, a compromise was forged to allow for land and financial resources be set apart to further this mission of UCC. Howard Butt, Jr. was instrumental in ensuring that ten acres on Ward Island be set aside from the transfer of property to be used for Christian educational studies. The Christian Education Activities Corporation (CEAC) was founded to serve as the legal successor to UCC. In this capacity, the organization would receive control over the one and a half million-dollar endowment that UCC had in place for religious studies.[cxxxvii][cxxxviii]

The UCC board transitioned to become the first CEAC board. They were charged with continuing the mission of Christian studies in South Texas. Theology courses were offered beginning in 1977, taught mostly by HPU Associate Professor Dr. Kenneth Bradshaw (1929-2013). Students at CCSU could also take the courses on religion as electives.[cxxxix] The Baptist Learning Center of South Texas (BLC) was established in 1980 on Ward Island. The student body of BLC was largely Baptist, and the curriculum was focused on religious studies. Coursework was offered by Corpus Christi State University, Howard Payne University, and the BLC. A partnership with Howard Payne University allowed for degrees to be conferred.[cxl][cxli]

In 1997, the BLC added a Master of Divinity degree to the offerings on Ward Island through a partnership with another BGCT affiliated University, Hardin-Simmons University of Abilene.[cxlii] In 2005, the Bill and Doris Stark Conference Center opened with four apartments to provide housing for faculty and a meeting room. In 2004, the BLC name was changed to the South Texas School of Christian Studies and later to Stark College and Seminary. This center remains devoted to Christian studies at its location on the eastern part of Ward Island and has sites in McAllen, Victoria, and San Antonio. Stark College continues the religious mission of UCC.[cxliii]

Construction of the Christian Learning Center (1980)

Alumni Update, June 1980. Special Collections and Archives, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

Stark College on Ward Island (2020)

Andrew Johnson

[i] Wrotenbery, R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[ii] Russell, M. & Murray, L. S. Baylor University. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/baylor-university

[iii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[iv] Celelli, T. (2012). Missions through education: The continuing legacy of the University of Corpus Christi and the South Texas School of Christian Studies. In M. E. Williams, Texas Baptist History (pp. 69-80). Texas Baptist Historical Society.

[v] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[vi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[vii] Celelli, T. (2012). Missions through education: The continuing legacy of the University of Corpus Christi and the South Texas School of Christian Studies. In M. E. Williams, Texas Baptist History (pp. 69-80). Texas Baptist Historical Society.

[viii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[ix] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[x] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xi] Delaney, C. (2013, May). Corpus Christi’s ‘University of the Air’. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2013/may/corpus-christis-university-air

[xii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xiii] Ehrlich, A. (2021, February 3). NAS-Chase Field trained pilots for nearly 50 years. Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[xiv] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xv] University of Corpus Christi plans huge expansion (1953, June 7). Dallas Morning News.

[xvi] Kreneck, H., Gammage, B., & Paschal, S. (2007). Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi: The Island University: 60 years, 1947-2007. Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi: Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi: Division of Institutional Advancement.

[xvii] Branning, (1989, January 12). Baptist opened university. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. 67.

[xviii] Wrotenbery, R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[xix] Celelli, T. (2012). Missions through education: The continuing legacy of the University of Corpus Christi and the South Texas School of Christian Studies. In M. E. Williams, Texas Baptist History (pp. 69-80). Texas Baptist Historical

[xx] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xxi] Sanders library to occupy site of Navy Library. (1947, June 8). Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 18.

[xxii] Branning, C. (1989, January 12). Baptist opened university. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 67.

[xxiii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xxiv] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xxv] Kreneck, T. , Gammage, B., & Paschal, S. (2007). Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi: The Island University: 60 years, 1947-2007. Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi: Division of Institutional Advancement.

[xxvi] Nelson, (1966, March 27). UCC aims at accreditation. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. 15.

[xxvii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xxviii] Branning, (1989, January 12). Baptist opened university. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. 67.

[xxix] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xxx] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin

[xxxi] Chase Field. National Register of Historic Places. https://npgallery.nps.gov/pdfhost/ docs/NRHP/Text/64500646.pdf

[xxxii] Garza (2020, August 22). Texas Department of Criminal Justice. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/unit_directory/ni.html

[xxxiii] Chase Field (2020, August 22). Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. https://lsuasc.tamucc.edu/ test-sites/ chase.xhtml

[xxxiv] George Cuddihy. USNA Virtual Memorial Wall. https://us-namemorialhall.org/index.php/GEORGE_T._CUDDIHY,_LT,_USN

[xxxv] Leatherwood, (2010, June 15). Naval Air Station, Corpus Christi. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https:// tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbn01

[xxxvi] Ward Island takes Comet Nine, 7-5. (1947,June 15). Corpus Christi Caller-Times,

[xxxvii] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1947). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of

[xxxviii] Hunter, C. A., & Hunter, L. G. (2000). Texas A&M University Charleston, SC: Arcadia.

[xxxix] Branning, C. (1989, January 12). Baptist opened university. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 67.

[xl] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1956). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[xli] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[xlii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[xliii] Tijerina, R. (1999, November 28). Education in Corpus Christi: A timeline. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. L7.

[xliv] Dodson, A. (1947, October 19). Cuddihy becomes collegiate as Baptist University moves in. The Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[xlv] Texas Baptists accept contract for Ward Island. (1947, November 26). Corpus Christi Caller and Daily Herald, p. 1.

[xlvi] Branning, C. (1989, January 12). Baptist opened university. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. 67.

[xlvii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[xlviii] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1948). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[xlix] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1949). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[l] UCC personnel begin moving to Ward Island. (1947, December 20). Corpus Christi Caller and Daily Herald, p. 24.

[li] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lii] Rosser, J. (1978, October 12). CCSU worker must move after years on campus. Corpus Christi Caller, p. 66.

[liii] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1948). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[liv] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lv] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1948). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[lvi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lvii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lviii] Fulton, C. C. (2017, May 12). ASU’s first four-year graduates walked 50 years ago. San Angelo Standard-Times.

[lix] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lx] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxii] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1952). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[lxiii] Dr. Miller toils to better UCC. (1964, November 4). Corpus Christi Caller-Times, p. 25.

[lxiv] Nelson, G. (1966, March 27). UCC aims at accreditation. Cor pus Christi Caller-Times, p. 15.

[lxv] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxvi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxvii] Fernandez, S. L. (2003, August 20). Ex-UCC president dies – Leonard Holloway served here in 1967. Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

[lxviii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxix] Central Texas Obituaries. (2003, August 20). Temple Daily Telegram. https://www.tdtnews.com/archive/arti-cle_f606157b- a872-5447-92e9-da73665232da.xhtml

[lxx] UCC alumni to support new A&I-Corpus Christi. (1973, February 11). Corpus Christi Caller-Times., p. 45.

[lxxi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxxii] Hall of Fame. Kenneth Maroney. Texas A&M University Corpus Christi Athletics. https://goislanders.com/hof.aspx?hof=32

[lxxiii] Hall of Fame. Bob Maroney. Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Athletics. https://goislanders.com/honors/hall-of-honor?hof=8

[lxxiv] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1950). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[lxxv] Baptist General Convention of Texas. (1951). Annual of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

[lxxvi] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxxvii] Wrotenbery, C. R. (1998). Baptist Island College. Fort Worth, Texas: Eakin Press.

[lxxviii] Bailey bridge to UCC to be removed today. (1962, May 15).Corpus Christi Caller, p. 30.