23 Rhetorical Analysis and Context

A rhetorical analysis asks you to “examine the interactions between a text, an author, and an audience.” However, before you can begin the analysis, you must first understand the historical context of the text and the rhetorical situation.

To locate a text’s historical context, you must determine where in history the text is situated—was it written in the past five years? Ten? One hundred? You should think about how that might affect the information being delivered. Once you determine the background of the text, you should determine the rhetorical situation (i.e. who, what, when, where, why). The following questions may help:

- What is the topic of the text?

- Who is the author? What are the author’s credentials, what sort of experiences has he or she had? How do his or her credentials, or lack of, connect (or not) with the topic of the text?

- Who is the target audience? Who did the author have in mind when he or she created the text?

- Who is the unintended audience? Are they related in any way to the target audience?

- What was the occasion, historical context, or setting? What was happening during the time period when the text was produced? Where was the text distributed or published?

- How does the topic relate to the author, audience, and occasion?

- What is the author’s purpose? Why did he or she create the text?

- In what medium was the text originally produced?

Meaning can change based on when, where, and why a text was produced, and meaning can change depending on who reads the text. Rhetorical situations affect the meaning of a text because it may have been written for a specific audience, in a specific place, and during a specific time. An important part of the rhetorical situation is the audience, and since many of the articles were not written with you, a college student in a college writing class, in mind, the meaning you interpret or recognize might be different from the author’s original target audience.

For example, if you read an article about higher education written in 2016, then you, the reader, are connected with and understand the context of the topic. However, if you were asked to read a text about higher education written in 1876, you would probably have a hard time understanding and connecting to it because you are not the target audience, and the text’s context (or rhetorical situation) has changed.

Further, the occasion for writing might be very different, too. Articles or scholarly works that are at least five years old may include out-of-date references and may not represent relevant or accurate information (e.g., think of the change regarding gay marriage in the past few years). Older works require that you investigate significant historical moments or changes that have occurred since the writing of the text.

Targeted audience, occasion, and the date, site, and medium of publication will all affect the way you, the reader, read a text. Therefore, it is your duty as a thoughtful reader to research these aspects in order to fully understand and conceptualize the text’s rhetorical situation. Furthermore, even though you might not be a member of the targeted audience or perhaps might not have even been alive during the production of a text, that does not mean that you cannot recognize rhetorical moves within it.

Rhetorical Context

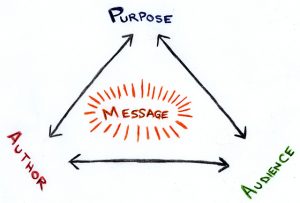

Any piece of writing is shaped by external factors before the first word is ever set down on the page. These factors are referred to as the rhetorical situation, or rhetorical context, and are often presented in the form of a pyramid.

The three key factors–purpose, author, and audience–all work together to influence what the text itself says, and how it says it. In this chapter, we will examine these along with the writing process and writing for transfer.

PURPOSE

Purpose will sometimes be given to you (by a teacher, for example), while other times, you will decide for yourself. As the author, it’s up to you to make sure that purpose is clear not only for yourself, but also–especially–for your audience. If your purpose is not clear, your audience is not likely to receive your intended message.

There are, of course, many different reasons to write (e.g., to inform, to entertain, to persuade, to ask questions), and you may find that some writing has more than one purpose. When this happens, be sure to consider any conflict between purposes, and remember that you will usually focus on one main purpose as primary.

Bottom line: Thinking about your purpose before you begin to write can help you create a more effective piece of writing.

WHY PURPOSE MATTERS

- If you’ve ever listened to a lecture or read an essay and wondered “so what” or “what is this person talking about,” then you know how frustrating it can be when an author’s purpose is not clear. By clearly defining your purpose before you begin writing, it’s less likely you’ll be that author who leaves the audience wondering.

- If readers can’t identify the purpose in a text, they usually quit reading. You can’t deliver a message to an audience who quits reading.

- If a teacher can’t identify the purpose in your text, they will likely assume you didn’t understand the assignment and, chances are, you won’t receive a good grade.

AUDIENCE

In order for your writing to be maximally effective, you have to think about the audience you’re writing for and adapt your writing approach to their needs, expectations, backgrounds, and interests. Being aware of your audience helps you make better decisions about what to say and how to say it. For example, you have a better idea if you will need to define or explain any terms, and you can make a more conscious effort not to say or do anything that would offend your audience.

Sometimes you know who will read your writing – for example, if you are writing an email to your boss. Other times you will have to guess who is likely to read your writing – for example, if you are writing a newspaper editorial. You will often write with a primary audience in mind, but there may be secondary and tertiary audiences to consider as well.

A Note on Audience

What is the Difference between an Audience and a Reader?

Thinking about the audience can be a bit tricky. Your audience is the person or group that you intend to reach with your writing. We sometimes call this the intended audience – the group of people to whom a text is intentionally directed. But any text likely also has an unintended audience, a reader (or readers) who read it even without being the intended recipient. The reader might be the person you have in mind as you write, the audience you’re trying to reach, but they might be some random person you’ve never thought of a day in your life. You can’t always know much about random readers, but you should have some understanding of who your audience is. It’s the audience that you want to focus on as you shape your message.

WHAT TO THINK ABOUT

When analyzing your audience, consider these points. Doing this should make it easier to create a profile of your audience, which can help guide your writing choices.

Background Knowledge or Experience — In general, you don’t want to merely repeat what your audience already knows about the topic you’re writing about; you want to build on it. On the other hand, you don’t want to talk over their heads. Anticipate their amount of previous knowledge or experience based on elements like their age, profession, or level of education.

Expectations and Interests — Your audience may expect to find specific points or writing approaches, especially if you are writing for a teacher or a boss. Consider not only what they do want to read about, but also what they do not want to read about.

Attitudes and Biases — Your audience may have predetermined feelings about you or your topic, which can affect how hard you have to work to win them over or appeal to them. The audience’s attitudes and biases also affect their expectations – for example, if they expect to disagree with you, they will likely look for evidence that you have considered their side as well as your own.

Demographics — Consider what else you know about your audience, such as their age, gender, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, political preferences, religious affiliations, job or professional background, and area of residence. Think about how these demographics may affect how much background your audience has about your topic, what types of expectations or interests they have, and what attitudes or biases they may have.

Useful Questions

Consider how the answers to the following questions may affect your writing:

- What is my primary purpose for writing? How do I want my audience to think, feel, or respond after they read my writing?

- Do my audience’s expectations affect my purpose? Should they?

- How can I best get my point across (e.g., tell a story, argue, cite other sources)?

- Do I have any secondary or tertiary purposes? Do any of these purposes conflict with one another or with my primary purpose?

APPLYING YOUR ANALYSIS TO YOUR WRITING

Here are some general rules about writing, each followed by an explanation of how the audience might affect it. Consider how you might adapt these guidelines to your specific situation and audience. (Note: This is not an exhaustive list. Furthermore, you need not follow the order set up here, and you likely will not address all of these approaches.)[1]

Add information readers need to understand your document / omit information readers don’t need. Part of your audience may know a lot about your topic, while others don’t know much at all. When this happens, you have to decide if you should provide an explanation or not. If you don’t offer an explanation, you risk alienating or confusing those who lack the information. If you offer an explanation, you create more work for yourself and you risk boring those who already know the information, which may negatively affect the larger view those readers have of you and your work. In the end, you may want to consider how many people need an explanation, whether those people are in your primary audience (rather than a secondary audience), how much time you have to complete your writing, and any length limitations placed on you.

Change the level of the information you currently have. Even if you have the right information, you might be explaining it in a way that doesn’t make sense to your audience. For example, you wouldn’t want to use highly advanced or technical vocabulary in a document for first-grade students or even in a document for a general audience, such as the audience of a daily newspaper, because most likely some (or even all) of the audience wouldn’t understand you.

Add examples to help readers understand. Sometimes just changing the level of information you have isn’t enough to get your point across, so you might try adding an example. If you are trying to explain a complex or abstract issue to an audience with a low education level, you might offer a metaphor or an analogy to something they are more familiar with to help them understand. Or, if you are writing for an audience that disagrees with your stance, you might offer examples that create common ground and/ or help them see your perspective.

Change the level of your examples. Once you’ve decided to include examples, you should make sure you aren’t offering examples your audience finds unacceptable or confusing. For example, some teachers find personal stories unacceptable in academic writing, so you might use a metaphor instead.

Change the organization of your information. Again, you might have the correct information, but you might be presenting it in a confusing or illogical order. If you are writing a report for a physics course for a professor who has his or her PhD, chances are you won’t need to begin it with a lot of background. However, you probably would want to include background information in the report if you were writing for a fellow student in an introductory physics class.

Strengthen transitions. You might make decisions about transitions based on your audience’s expectations. For example, most teachers expect to find topic sentences, which serve as transitions between paragraphs. In a shorter piece of writing such as a memo to co-workers, however, you would probably be less concerned with topic sentences and more concerned with transition words. In general, if you feel your readers may have a hard time making connections, providing transition words (e.g., “therefore” or “on the other hand”) can help lead them.

Write stronger introductions – both for the whole document and for major sections. In general, readers like to get the big picture up front. You can offer this in your introduction and thesis statement, or in smaller introductions to major sections within your document. However, you should also consider how much time your audience will have to read your document. If you are writing for a boss who already works long hours and has little or no free time, you wouldn’t want to write an introduction that rambles on for two and a half pages before getting into the information your boss is looking for.

Create topic sentences for paragraphs and paragraph groups. A topic sentence (the first sentence of a paragraph) functions much the same way an introduction does – it offers readers a preview of what’s coming and how that information relates to the overall document or your overall purpose. As mentioned earlier, some readers will expect topic sentences. However, even if your audience isn’t expecting them, topic sentences can make it easier for readers to skim your document while still getting the main idea and the connections between smaller ideas.

Change sentence style and length. Using the same types and lengths of sentences can become boring after awhile. If you already worry that your audience may lose interest in your issue, you might want to work on varying the types of sentences you use.

Use graphics, or use different graphics. Graphics can be another way to help your audience visualize an abstract or complex topic. Sometimes a graphic might be more effective than a metaphor or step-by-step explanation. Graphics may also be an effective choice if you know your audience is going to skim your writing quickly; a graphic can be used to draw the reader’s eye to information you want to highlight. However, keep in mind that some audiences may see graphics as inappropriate.

AUTHOR

The final unique aspect of anything written down is who it is, exactly, that does the writing. In some sense, this is the part you have the most control over–it’s you who’s writing, after all! You can harness the aspects of yourself that will make the text most effective to its audience, for its purpose.

Analyzing yourself as an author allows you to make explicit why your audience should pay attention to what you have to say, and why they should listen to you on the particular subject at hand.

Licenses and Attributions CC LICENSED CONTENT,

Composing Ourselves and Our World, Provided by: the authors. License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

CC LICENSED CONTENT INCLUDED

This chapter contains as adaption of Analyzing Your Audience. Provided by: Wright State University Writing Center. Located at: https://uwc.wikispaces.com/ Analyzing+Your+Audience. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution- NonCommercial

This chapter contains material from “The Word on College Reading and Writing” by Monique Babin, Carol Burnell, Susan Pesznecker, Nicole Rosevear, Jaime Wood, OpenOregon Educational Resources, Higher Education Coordination Commission: Office of Community Colleges and Workforce Development is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

1st Edition: A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing (No Longer Updated) by Melanie Gagich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

MULTIMEDIA CONTENT INCLUDED

Image 1: Image of Rhetorical Triangle. Authored by: Ted Major. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/jbqVvR. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Media Attributions

- image3