3 Simple Meters

Now that you are familiar with beats and divisions, we will learn about how they work within simple meters.

3.1 INTRODUCTION

In the last chapter, we learned several things about beats:

- Any note can equal one beat, and that beat can be evenly divided into two (creating a division) and evenly divided into four (creating a subdivision).

- Not all parts of the beat are created equal: notes that fall on the beat (“1”) are stronger than other parts of the beat.

- In order to process music more efficiently, notes with flags within beats are grouped together with beams.

Just as notes are beamed together into beats, beats are also grouped together so musicians can process music more efficiently. Grouped beats are separated by bar lines. The distance from one bar line to the next is called a measure or bar. Most commonly, there are two, three, or four beats within a measure.

Recall that not all parts of the beat have equal weight. Similarly, not all beats of the measure have equal weight. Beats that fall on the first beat are stronger than the others. The accented first beat is called the downbeat. The downbeat’s accent is not as obvious or strong as notes that have accent symbols, but there is a subtle emphasis on the downbeat.

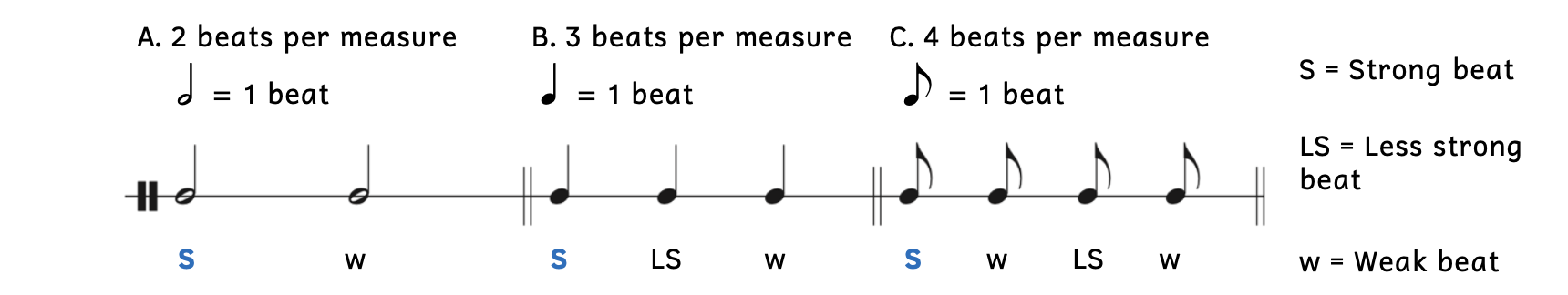

Example 3.1.1. Weighted beats

In Example 3.1.1, the downbeats are marked by the blue S’s.

- Example 3.1.1A:

- The half note gets one beat and there are two beats per measure.

- When there are two beats per measure, the downbeat is strong (S) and the second beat is weak (w).

- Example 3.1.1B:

- The quarter note gets one beat and there are three beats per measure.

- When there are three beats per measure, the downbeat is strong, the second beat is less strong (LS), and the third beat is weak.

- Example 3.1.1C:

- The eighth note gets one beat and there are four beats per measure.

- Notice that the eighth notes are not beamed together. This is because each eighth note is equal to one beat. We only beam them when they combine to create one beat.

- When there are four beats per measure, the downbeat is strong, the third beat is less strong, and the second and fourth beats are weak.

Strong beats are accented while weak beats are unaccented. Tap your foot while listening to the next three examples.

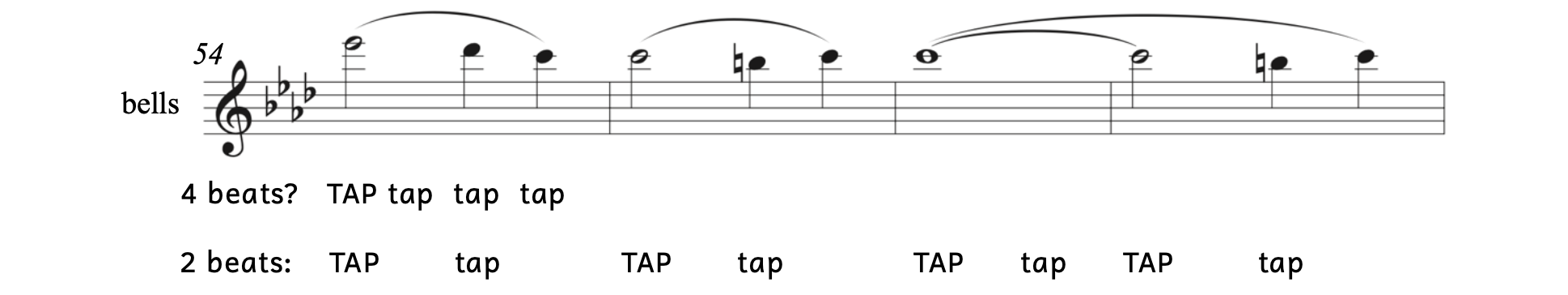

Example 3.1.2. Two beats per measure: Sousa[1], “The Stars and Stripes Forever”

At first glance, you might be tempted to think the quarter note receives one beat and there are four beats per measure in Example 3.1.2. However, when listening to the excerpt, do you tap your foot four times or only twice per measure? Chances are you only tap your foot twice per measure, meaning that there are two beats per measure and the half note receives one beat.

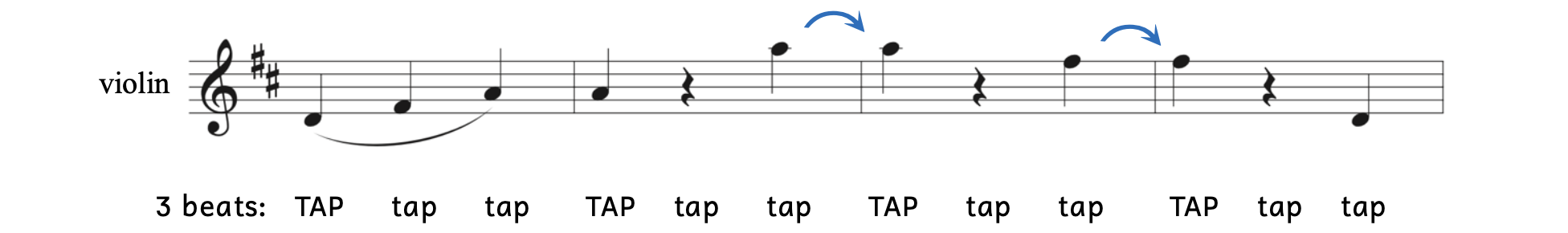

Example 3.1.3. Three beats per measure: Strauss[2], “The Blue Danube Waltz”

There are three beats per measure in Example 3.1.3 and the quarter note gets one beat. The downbeat is more emphasized than the other two beats in this example by Strauss. Indeed, the downbeat is so strong that the third beat of measures 2 and 3 actually sound more like an introduction to the next downbeat (shown by the arrows), rather than the last beat of the measure.

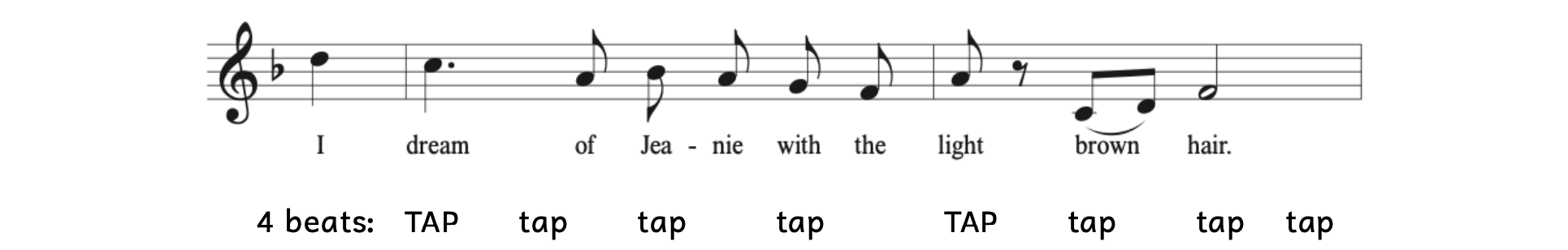

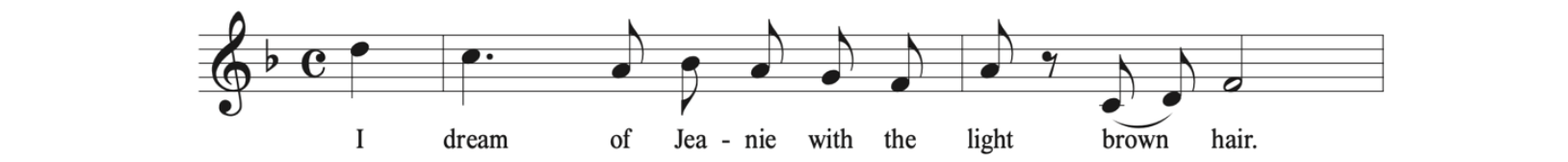

Example 3.1.4. Four beats per measure: Foster[3], “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair”

There are four beats per measure in Example 3.1.4. Since beats 1 and 3 are stronger than beats 2 and 4 when there are four beats per measure, it may be difficult to distinguish between two beats per measure and four beats per measure. However, because Example 3.1.4 is so slow, it is more likely to tap your foot four times per measure.

You may have noticed two things about Example 3.1.4:

- The example begins with a single note called an anacrusis or upbeat. We will learn about the upbeat in detail in Section 3.7.

- The eighth notes are not beamed according to beats. This is because the music is a vocal score. Music for voices will often disregard beaming in order to match notes with syllables and words.

In the three examples above, the number of beats and accented downbeat repeat in every measure. For instance, Example 3.1.3 has three beats per measure and this applies to every measure. When the same beats are accented within repeated groups of measures, it creates a meter. In this chapter, we will learn about the simple meters, which is a way of grouping measures where the beat evenly divides into two.

Meter

- Meter is the recurring regular pattern of beats.

- Beats are organized into groups of two, three, or four, where the downbeat always has the strongest accent.

- Simple meters are meters in which the beat is a note (not a dotted note) that divides evenly into two.

3.2 TIME SIGNATURES

We learned that beats can equal any note, but the half note, quarter note, and eighth note are most common. We also learned that beats are organized into groups separated by bar lines, and that groups of two, three, and four are most common. We can communicate all this information with a time signature. A time signature consists of two numbers (one above the other) at the beginning of a piece of music. In two cases, the time signature is a symbol instead of two numbers.

This chapter focuses on simple meters, which means that the beat is a note (as opposed to a dotted note) that is evenly divided into two. Time signatures in simple meters are simple to interpret.

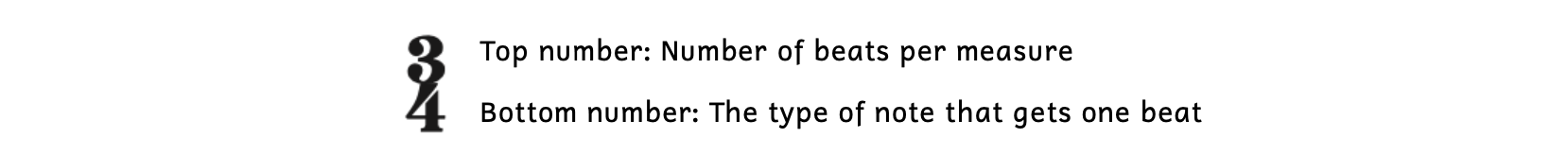

Example 3.2.1. Time signature in simple meter

- The top number of a time signature in simple meter refers to the number of beats per measure.

- We learned that there are most commonly two, three, or four beats per measure, so the top number will be 2, 3, or 4.

- The bottom number of a time signature in simple meter refers to the type of note that gets one beat.

- We learned that the half note, quarter note, and eighth note are most commonly equal to one beat, so the bottom number is usually 2, 4, or 8. The quarter-note beat (4) is most common, but you may also come across the half-note beat (2) and eighth-note beat (8).

- Although other note values such as the sixteenth-note beat (16) and thirty-second-note beat (32) are possible, they are not very common.

In one symbol, Example 3.2.1 tells us that there are three beats per measure and that the quarter note is equal to one beat. One common mistake is that students will write a number on the bottom that does not exist, such as 3. Remember that the bottom number represents a note value and since there is no such thing as a third note, 3 cannot be on the bottom.

There are two time signatures that do not have numbers; instead, they have their own symbol.

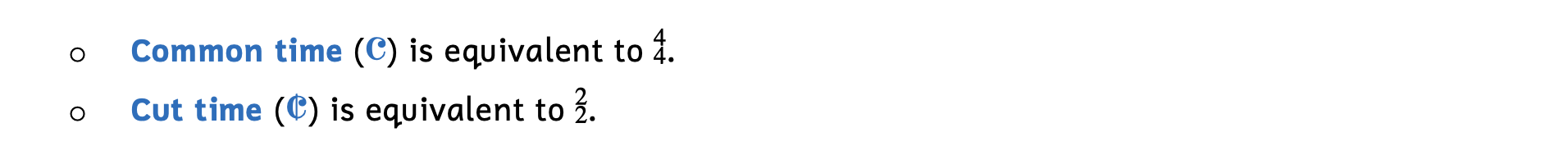

If we take the same examples from Example 3.1.1 and add time signatures, we get Example 3.2.2.

Example 3.2.2. Added time signatures

- Example 3.2.2A: The time signature tells us there are two beats per measure and the half note gets one beat.

- This example could have also been written in cut time.

- Example 3.2.2B: The time signature tells us there are three beats per measure and the quarter note gets one beat.

- Example 3.2.2C: The time signature tells us there are four beats per measure and the eighth note gets one beat.

Previously, when we used rhythm syllables to count rhythms, we only used the number “1” because we were only applying it to one beat. Now that we are learning about two, three, and four beats per measure, we will use other numbers for notes that fall on the beat that is not the downbeat. Refer to Example 3.2.2A:

- Because there are two beats per measure, the downbeat is beat one and the second half note is beat two (not beat three).

- We count “1” for the first half note and “2” for the second half note.

We can take what we learned about divisions and subdivisions and fill these measures with different rhythms.

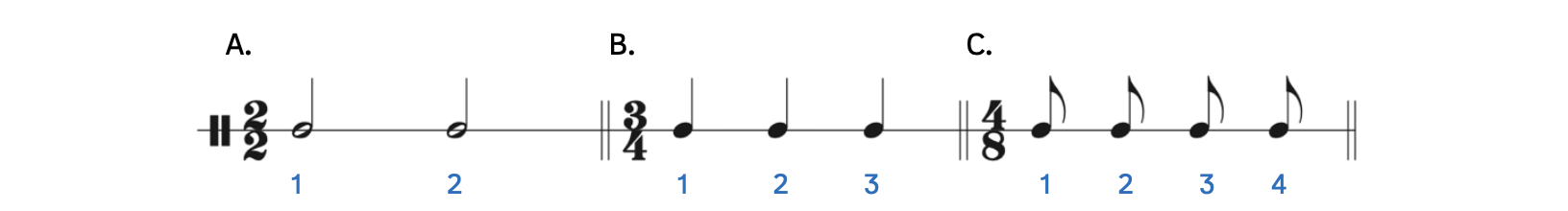

Example 3.2.3. Rhythms

Notice that all the examples above end on a strong beat. This is important to remember—do not end on a weak beat.

- Example 3.2.3A:

- Because the half note equals one beat, the division is two quarter notes and the subdivision is four eighth notes.

- The half-note beat is often challenging for students because they want to think of the quarter note as the beat. However, you need to shift perspective and think of a quarter note as half of a beat.

- In measure 2, there are four eighth notes beamed together. Because there are four notes beamed together, we immediately know that this is a subdivision and not a division.

- In measure 3, we cannot beam “1 e – a” because the quarter note does not have a flag.

- In measure 4, the final note ends on the strong downbeat. There is a long dash after the rhythm syllable “1” because it is held out beyond beat 2.

- Example 3.2.3B:

- Because the quarter note equals one beat, the division is two eighth notes and the subdivision is four sixteenth notes.

- Notice how helpful the beaming is to distinguish beats.

- Since there are only three quarter-note beats per measure, we cannot end with a whole note (because that would equal four quarter notes). Instead, a dotted half note falls on the downbeat and fills the final measure.

- Example 3.2.3C:

- Because the eighth note equals one beat, the division is two sixteenth notes and the subdivision is four thirty-second notes.

- The first eighth note is not beamed to the next two sixteenth notes because an eighth note is equal to one beat.

- Compare the two boxed areas in Example 3.2.3. The rhythms are the same (eighth note + two sixteenth notes), but because the note value of the beats differ, they are written (and counted) differently.

- This example does not end on the downbeat, but on beat 3. This is acceptable because beat 3 is still a strong beat (but less strong than the downbeat).

Remember that rests are the same as notes, but represent silence. Any of the notes in Example 3.2.3 could be substituted with its equivalent rest.

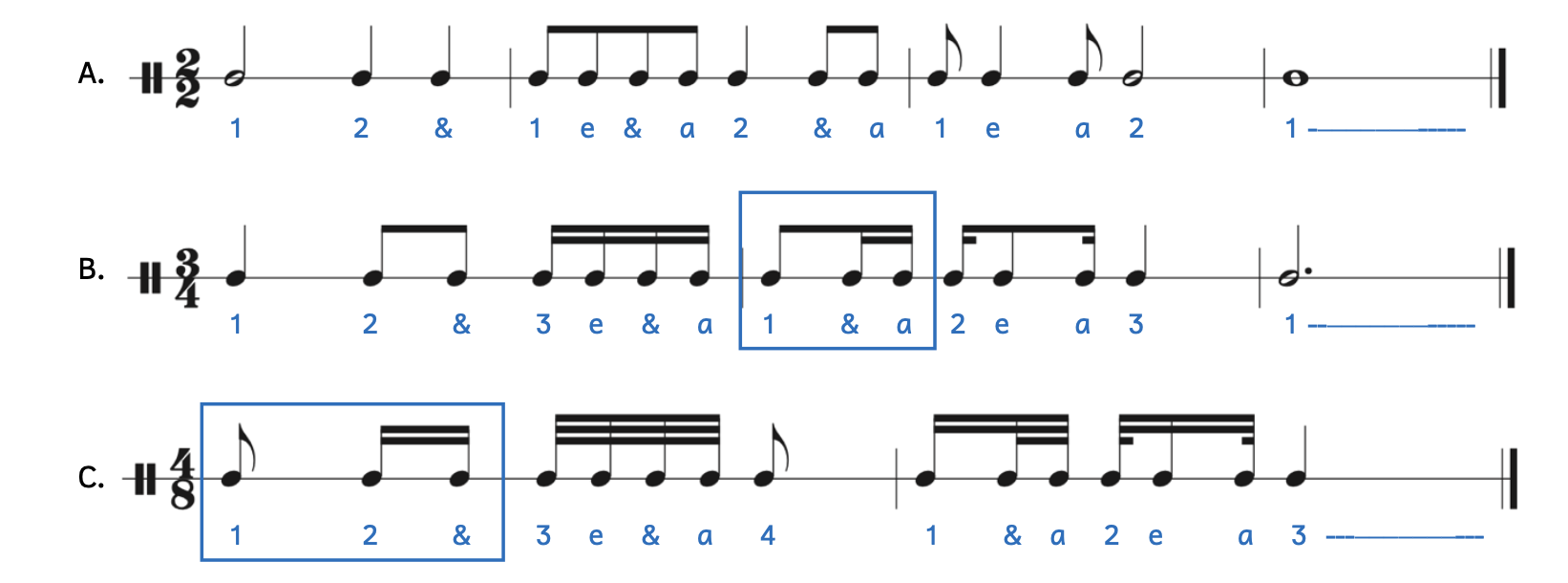

When writing rhythms correctly within a time signature, some students find it helpful to draw a box around each beat, then write the beaming correctly within each beat.

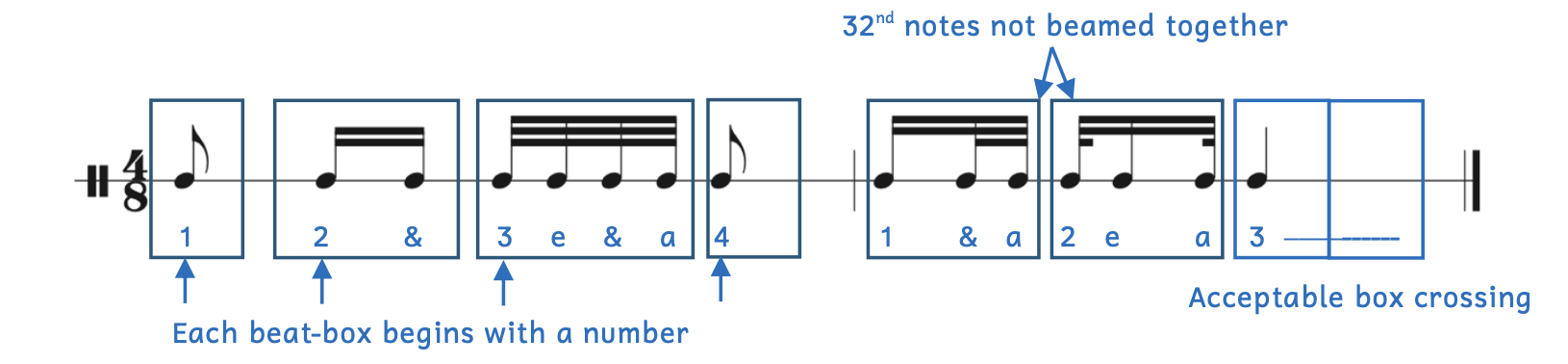

Example 3.2.4. Beat-boxes

When we box rhythm into separate beat-boxes, the ability to read music quickly becomes much easier.

- Each box represents a beat and each box begins with a number.

- In measure 2, there are three thirty-second notes between beats 1 and 2. However, the three thirty-second notes are not beamed together because they belong to different beats.

There is one anomaly in Example 3.2.4. Notice the last quarter note—it crosses into two boxes. In the rhythm syllables, this is shown by the long dash. Crossing boxes is acceptable when longer note values cross into other beats only if they begin on a strong beat. In Example 3.2.4, beat 3 is a strong beat in 4/8. If you look back to Example 3.2.3, each example concludes with a longer note value that crosses into other beats. In each example, this is acceptable because they all start on a strong beat.

Another anomaly you may come across is four eighth notes beamed together in 4/4. When the quarter note equals one beat, we expect two eighth notes to be beamed together; four notes beamed together imply a subdivision. However, four eighth notes are often beamed together in common time. Recall that when there are four beats per measure, the downbeat is the strongest, followed by beat 3. Because beats 1 and 3 are stronger, four eighth notes are beamed together.

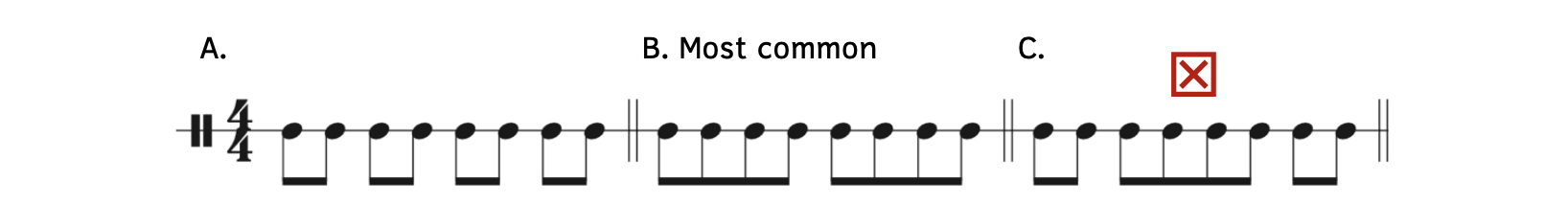

Example 3.2.5. Beaming in 4/4

- Example 3.2.5A: The time signature 4/4 literally means there are four quarter-note beats per measure. Typically, the quarter-note beat divides into two eighth notes, which are beamed together. Although this seems correct, there is another way that occurs more often (see Ex. 3.2.5B).

- Example 3.2.5B: In 4/4, it is more common to beam together four eighth notes. This is allowable because both beats 1 and 3 are strong. Be careful to not assume the four eighth notes are a subdivision.

- Example 3.2.5C: This type of beaming is incorrect because the group of four eighth notes begins on beat 2, which is a weak beat.

Let us return to Examples 3.1.2, 3.1.3, and 3.1.4 and see which time signatures are used.

Example 3.2.6. Sousa, “The Stars and Stripes Forever”

Example 3.2.6 begins at measure 54. The time signature is only written once at the start of the piece, but has been added here for convenience . Recall that we only tapped our foot twice per measure (Example 3.1.2). This resulted in the half note equaling one beat and the division of two quarter notes. Therefore, the time signature is cut time (or 2/2).

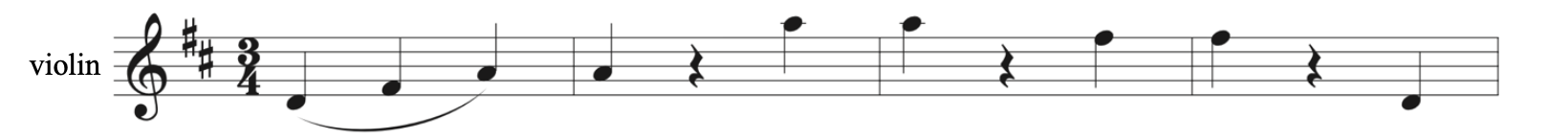

Example 3.2.7. Strauss, “The Blue Danube Waltz”

Earlier, we discovered that we tap our foot three times per measure in the Strauss example (Example 3.1.3). Because there are three beats per measure, a quarter note gets one beat. As a result, the time signature is 3/4 (Example 3.2.7). A waltz is a dance that has three beats per measure, so this time signature is no surprise.

Example 3.2.8. Foster, “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair”

As previously mentioned, the vocal score for Example 3.2.8 does not show beaming. However, in Example 3.1.4, we established that because of the slow tempo, we tapped our foot four times per measure. (As mentioned earlier, this example begins with an anacrusis, which we will learn about later.) This gives rise to a quarter-note beat. Therefore, the time signature is common time (or 4/4).

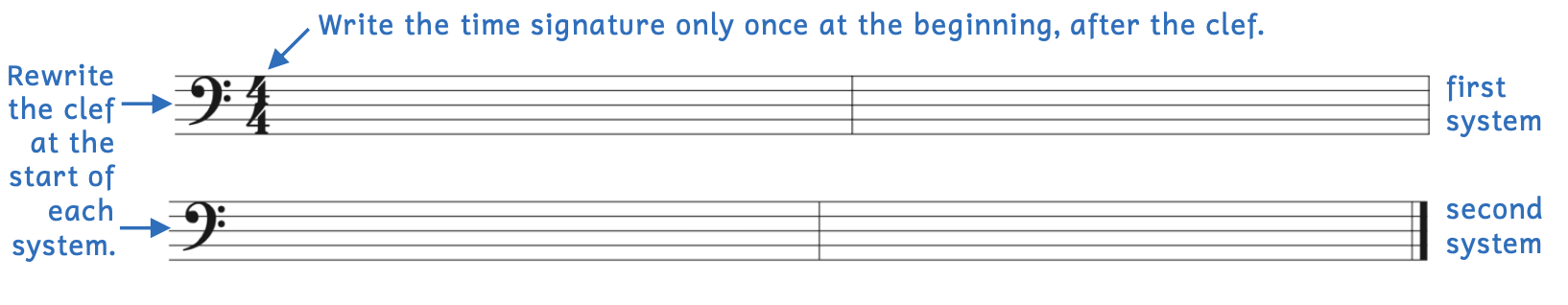

The time signature is only written once at the beginning as opposed to clefs, which are written for every system.

Example 3.2.9. Time signature versus clef

- Each system must begin with a clef.

- The time signature only appears at the start of the composition or when the time signature changes. Do not rewrite the time signature at the start of each system.

- Every system must end with a bar line if the measure is complete.

- Sometimes students will not add a bar line at the end of a system, assuming it is unnecessary. However, think of the bar line as a period at the end of a sentence. Although it may be obvious that it is the end of your sentence, it would look very odd if your sentence did not end with a period

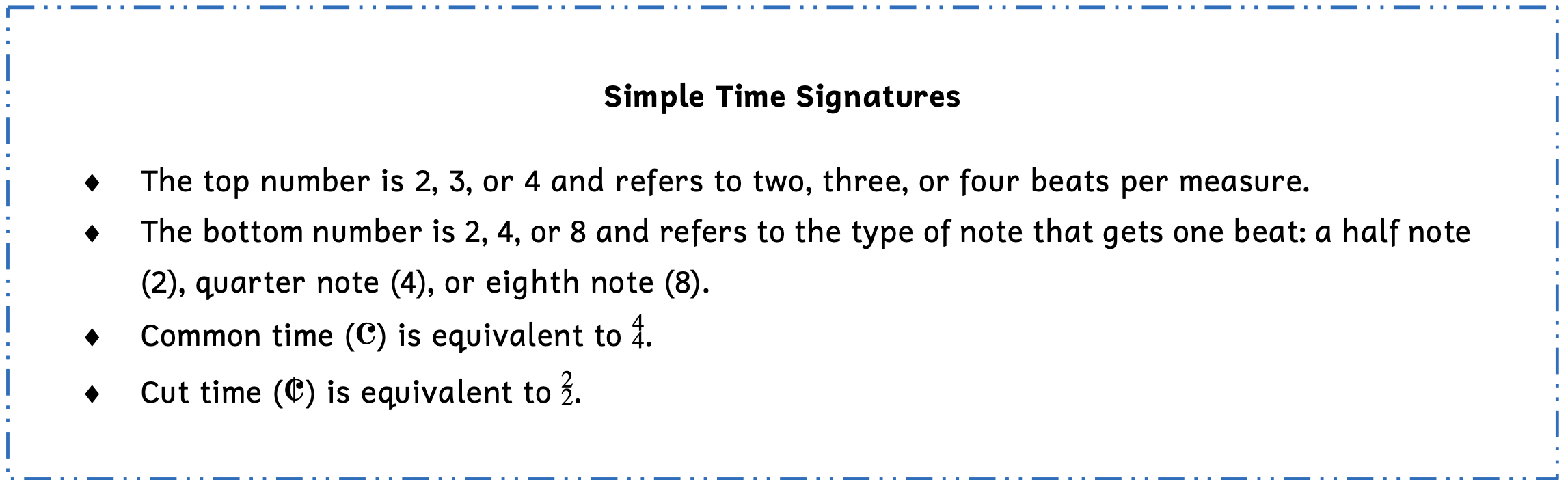

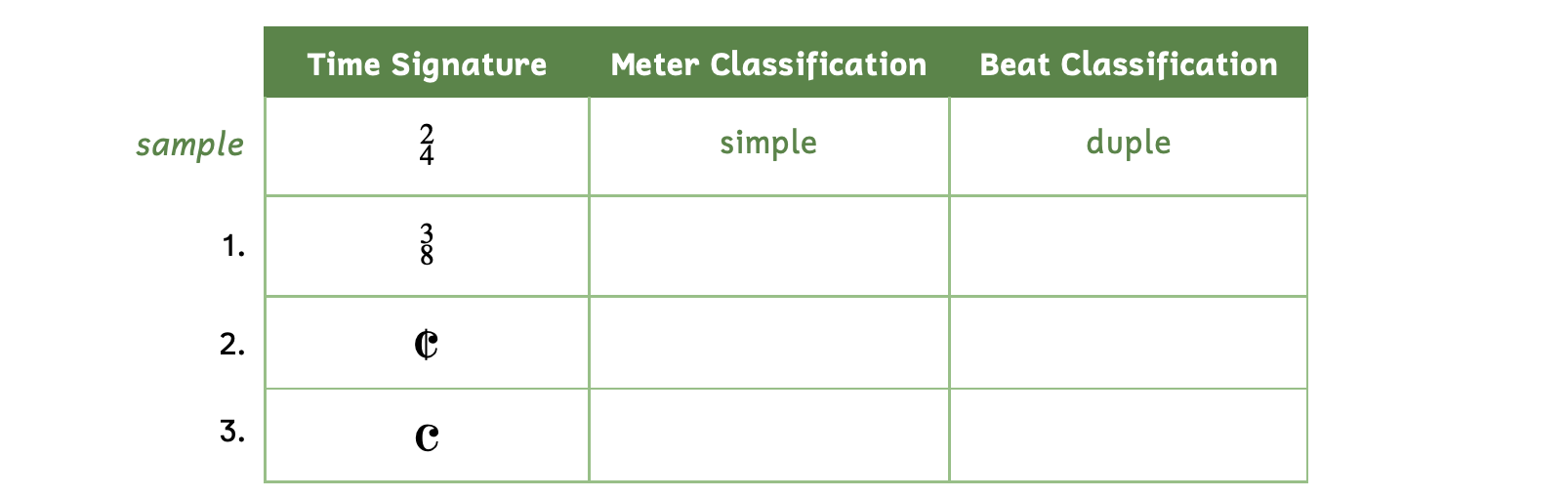

Practice 3.2A. Interpreting Simple Time Signatures

Directions:

- Complete the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) 4 beats per measure; quarter note equals one beat

3) 3 beats per measure; eighth note equals one beat

4) 2 beats per measure; half note equals one beat

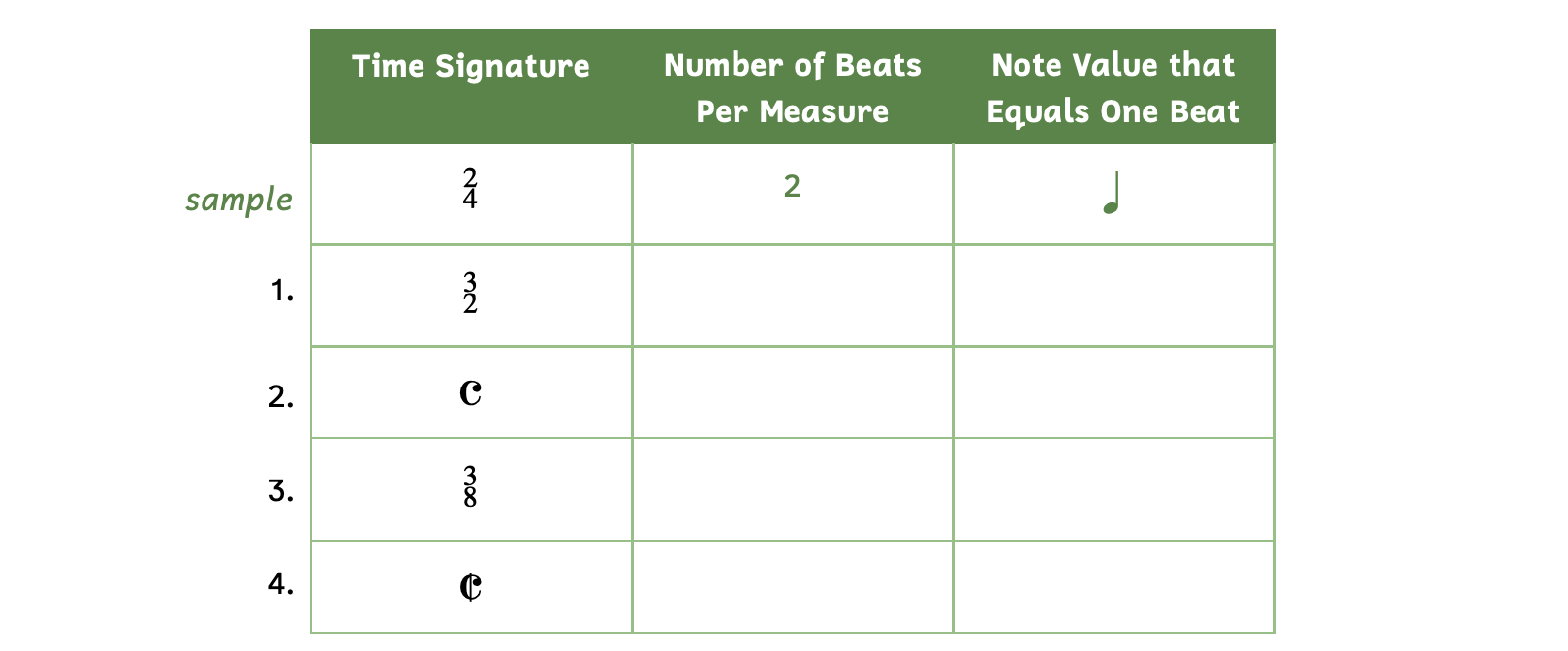

Practice 3.2B. Assigning Time Signatures to Simple Meters

Directions:

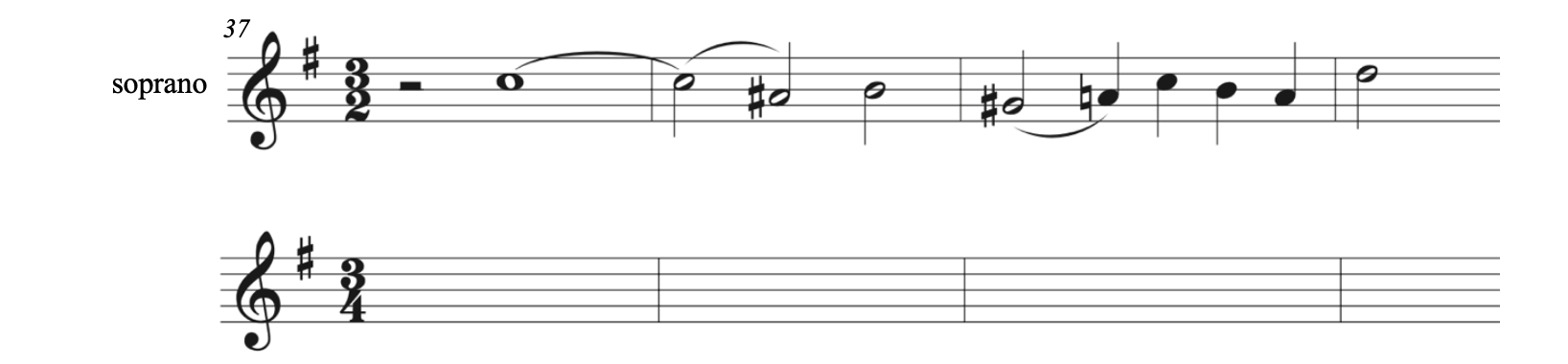

- Listen to the following melodies and write the most likely time signature onto the staff.

1. Tchaikovsky[4], 1812 Overture

2. Tchaikovsky, “Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker

3. Tchaikovsky, “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy,” from The Nutcracker

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) 3/4

3) 2/4

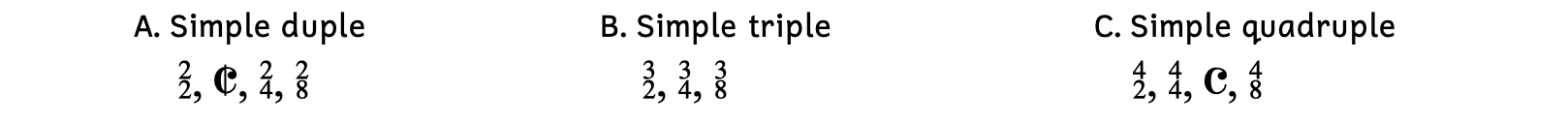

3.3 METER AND BEAT CLASSIFICATIONS

Time signatures can be classified by meter and beat.

- We learned that a simple meter is a type of meter classification where the beat evenly divides into two. When the top number of a time signature is 2, 3, or 4, it tells us it is simple and that there are two, three, or four beats per measure.

- Having two, three, or four beats per measure refers to a beat classification. Beat classifications can be duple (2), triple (3), or quadruple (4). We combine beat and meter classifications to describe time signatures.

Example 3.3. Meter and beat classification

Notice that the bottom number of the time signature does not matter when we refer to meter and beat classifications.

- Top number 2 = simple duple

- Top number 3 = simple triple

- Top number 4 = simple quadruple

Refer back to Examples 3.2.6-3.2.8:

- Example 3.2.6: Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever” is in simple duple because the time signature is cut time.

- Example 3.2.7: Strauss’s “The Blue Danube Waltz” is in simple triple because of the 3/4 time signature.

- Example 3.2.8: Foster’s “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair” is in simple quadruple because the time signature is common time.

Meter and Beat Classification

If the top number of the time signature is 2, 3, or 4, the meter and beat classification is simple duple, simple triple, or simple quadruple, respectively.

Practice 3.3. Classifying Simple Time Signatures

Directions:

- Fill in the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) Meter classification is simple; beat classification is duple.

3) Meter classification is simple; beat classification is quadruple.

3.4 WHOLE RESTS

As we learned, notes and their corresponding rests are equivalent. For example, a quarter note and a quarter rest are equivalent. However, the whole note and the whole rest are not always equivalent.

The whole note is worth four beats if a quarter note is worth one beat; it is worth two beats if a half note is worth one beat. This means that in the time signatures 4/4 (common time) or 2/2 (cut time), a whole note will fill an entire measure. However, in other time signatures, you cannot use a whole note because it is too large or too small.

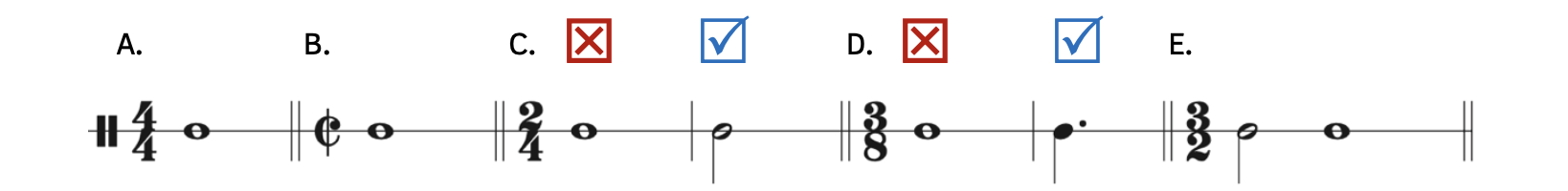

Example 3.4.1. Whole note

- Example 3.4.1A: A whole note fills an entire measure because there are four quarter notes in one measure.

- Example 3.4.1B: A whole note fills an entire measure because there are two half notes in one measure.

- Example 3.4.1C: You could not use a whole note in 2/4 (m. 3), because 2/4 has only two quarter notes per measure. You must use a half note to fill the measure (m. 4).

- Example 3.4.1D: You could not use a whole note in 3/8 (m. 5), because 3/8 has only three eighth notes per measure. You must use a dotted quarter note to fill the measure (m. 6).

- Example 3.4.1E: In 3/2, there are three half notes in one measure. In this case, a whole note does not fill an entire measure. Instead, a whole note is only worth two beats. In order for the measure to be complete, the measure requires another half note.

Whereas all other notes and their corresponding rests are equivalent (e.g., a half note and a half rest are always worth the same value), whole notes and whole rests are different: in most cases, a whole rest literally refers to a whole measure of rest.

- As we saw in Example 3.4.1, the whole note varies in value depending on the time signature.

- The whole rest always means an entire measure of rest, unless it is in a time signature in which a whole note would not fill the entire measure and there is another note in the measure.

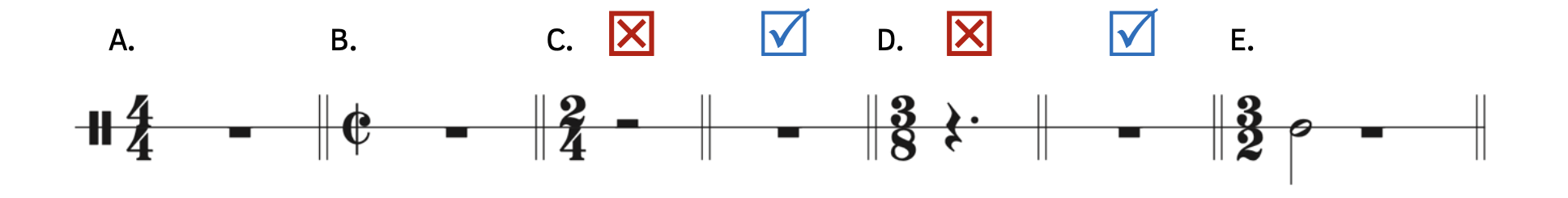

Example 3.4.2. Whole rest

- Example 3.4.2A: A whole rest fills an entire measure.

- Example 3.4.2B: A whole rest fills an entire measure.

- Example 3.4.2C: In 2/4, a half note would fill an entire measure.

- However, writing a half rest is incorrect (measure 3).

- Instead, a whole rest fills an entire measure (measure 4).

- Example 3.4.2D: In 3/8, a dotted quarter note would fill an entire measure.

- However, writing a dotted quarter rest would be incorrect (measure 5).

- Instead, a whole rest fills an entire measure (measure 6).

- Example 3.4.2E: In 3/2, the half note is equal to one beat and there are three beats in one measure.

- The half note is worth one beat and the whole rest is worth two beats: the whole rest does not mean a whole measure of rest. In order to avoid confusion, composers will often use two half rests instead of a whole rest.

- A whole rest by itself in 3/2 means a whole measure of rest.

The following three excerpts illustrate examples using whole rests.

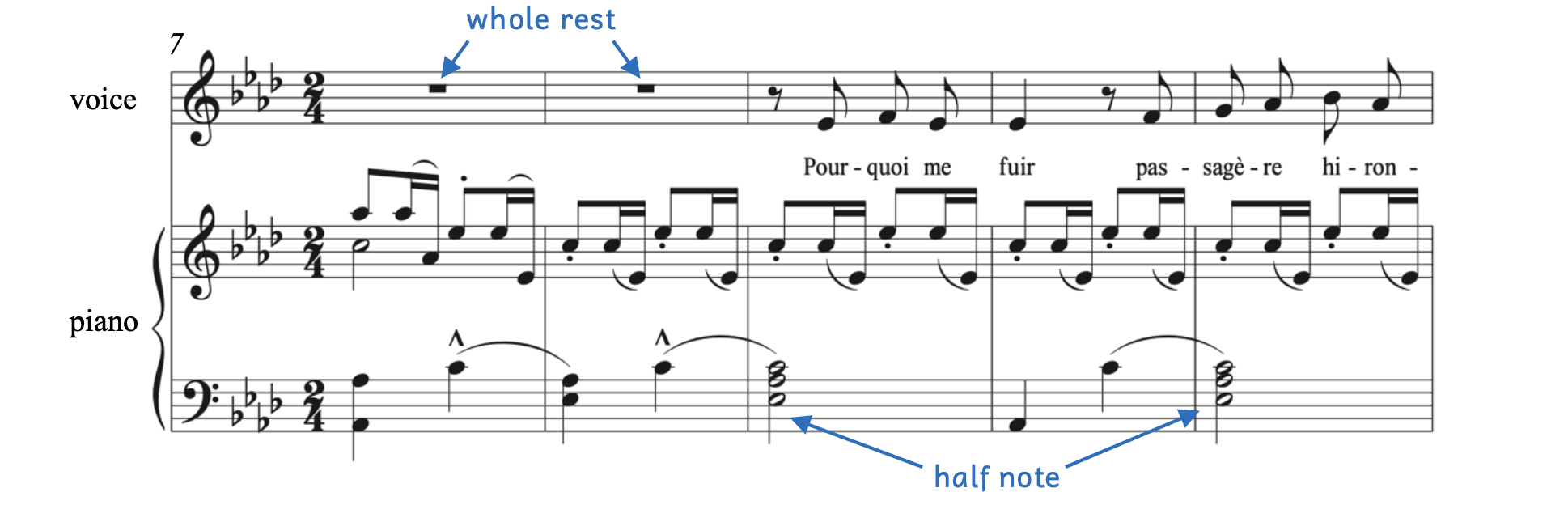

Example 3.4.3. Whole rests: Bertin[5], L’Hirondelle

Example 3.4.3 begins at measure 7. Time signatures are usually written only at the start of the composition, but one has been added here for convenience.

In 2/4, there are two beats per measure and a quarter note receives the beat.

- When a note fills an entire measure, the note is a half note (see bass clef, measures 9 and 11).

- However, when a rest fills an entire measure, the rest is a whole rest (see voice, measures 7 and 8).

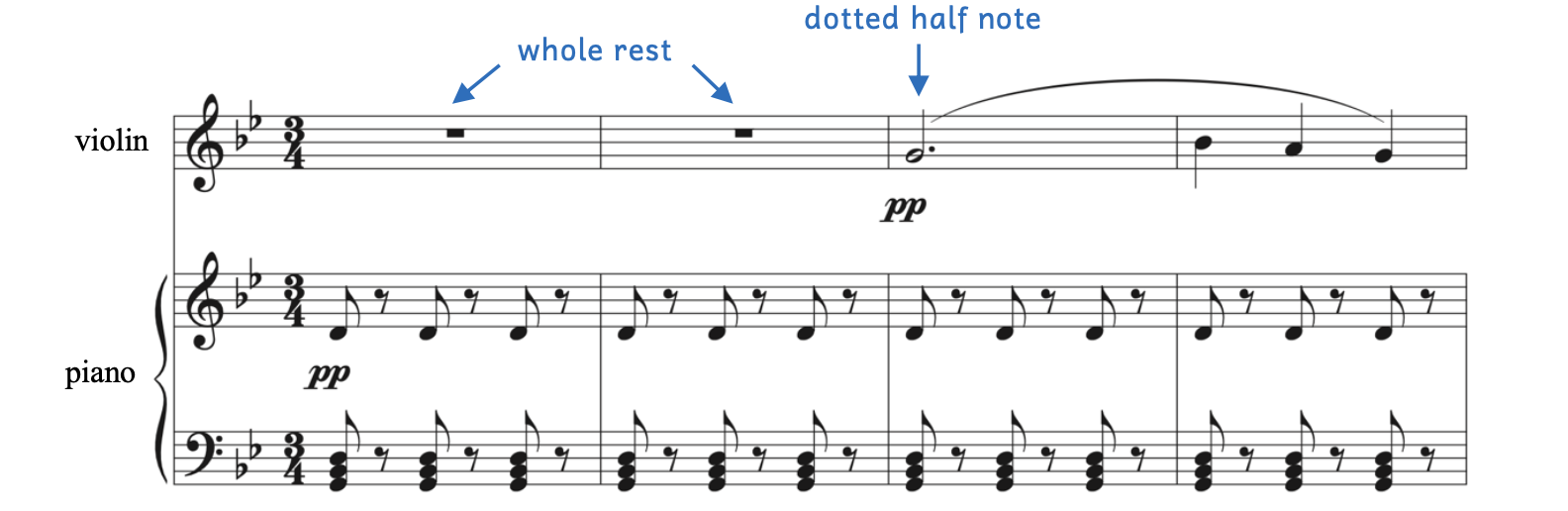

Example 3.4.4. Whole rests: Bertin, Piano Trio, Op. 10, Largo

In 3/4, there are three beats per measure and a quarter note receives the beat.

- When a note fills an entire measure, the note is a dotted half note (see violin, measure 3).

- However, when a rest fills an entire measure, the rest is a whole rest (see violin, measures 1 and 2).

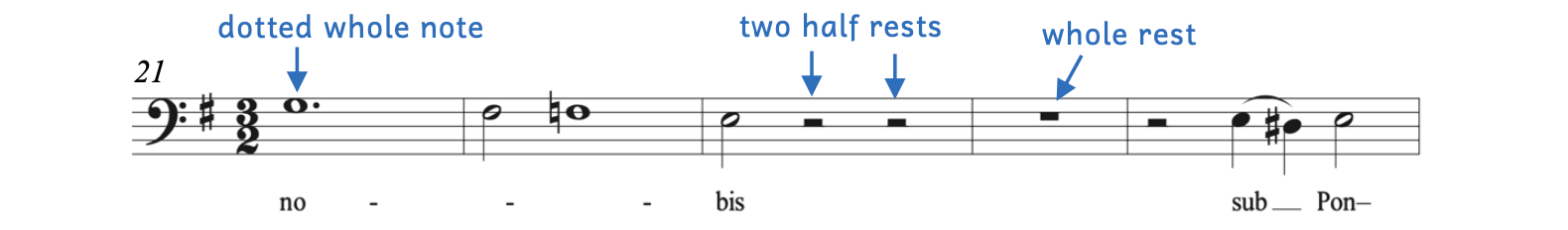

Example 3.4.5. Whole rest: Bach[6], “Crucifixus” from Mass in B Minor, BWV 232

Example 3.4.5 begins at measure 21, but a time signature has been added here for convenience.

In 3/2, there are three beats per measure where a half note receives the beat.

- When a note fills an entire measure, the note is a dotted whole note (see measure 21).

- However, when a rest fills an entire measure, the rest is a whole rest (see measure 24).

- Measure 23 requires two beats of rest. Rather than a whole rest, there are two half rests to avoid confusion with the following whole rest.

Whole Rest

Whole rests literally mean a whole measure of rest unless it is in a time signature in which a whole note would not fill the entire measure and there is another note in the measure.

Practice 3.4. Adding Rests to Measures

Directions:

- Add rests to complete each measure when necessary.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

3.5 TIES

Listen to the first four measures of Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstances.” It may be familiar to you if you ever attended a graduation ceremony.

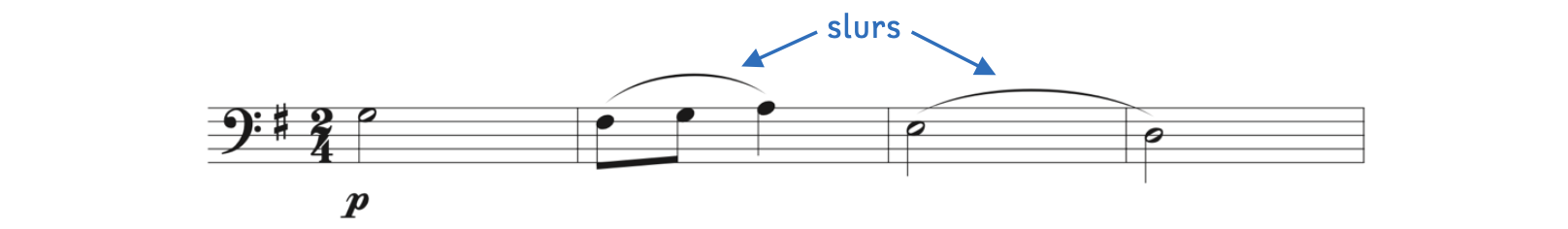

Example 3.5.1. Slurs: Elgar[7], Pomp and Circumstances Military March, Op. 39, No. 1

Recall that the curved lines connecting two or more notes are called slurs. Notes between the ends of slurs are to be performed smoothly.

Now listen to the next four measures of Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstances.”

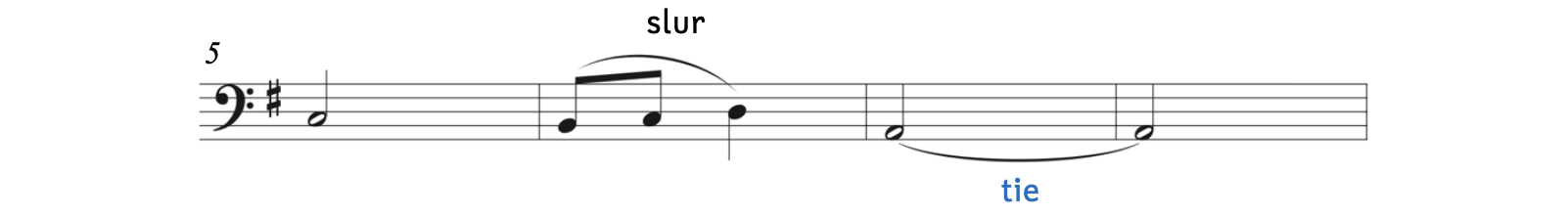

Example 3.5.2. Tie: Elgar, Pomp and Circumstances Military March, Op. 39, No. 1

Did you notice that the final A was not replayed? Instead, the A in measure 7 was held out for two bars. This is because the curved line connecting the two As is a not a slur, but a tie. A tie is a curved line that connects two of the same pitches and holds out the note (i.e., the note is sustained and not resounded).

The symbol for a tie is the same as the symbol for a slur (i.e., a curved line connecting noteheads). There are several ways to tell the difference between a tie and a slur.

- Ties connect the same note without any notes in between.

- Slurs connect different notes or the same note with notes in between.

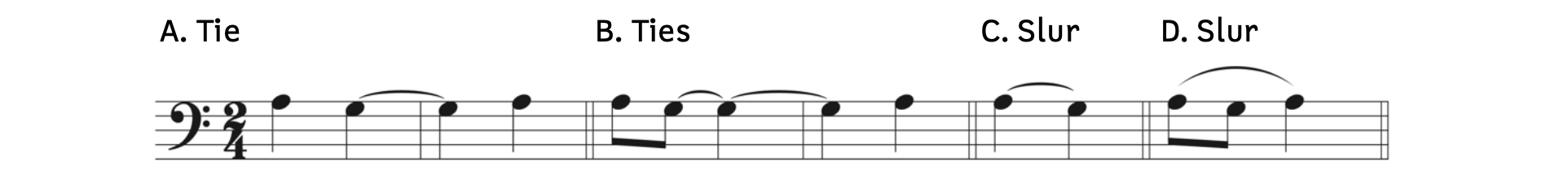

Example 3.5.3. Ties versus slurs

- Example 3.5.3A: This is a tie because it is connecting the same note without any notes in between (G to G).

- Example 3.5.3B: These are ties because they are connecting the same note without any notes in between (G to G to G).

- Example 3.5.3C: This is a slur because it is connecting different notes (A to G).

- Example 3.5.3D: This is a slur because although it is connecting the same note (A to A), there is a different note (G) in between.

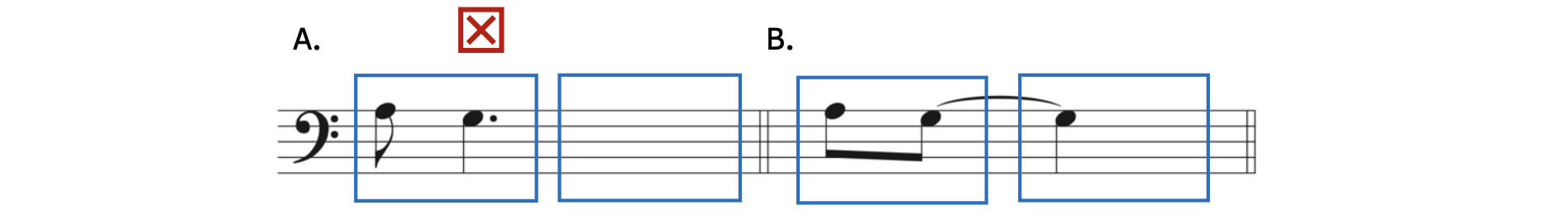

You may have wondered why a dotted quarter note was not used in Example 3.5.3B. The answer becomes clear when we add beat-boxes.

Ex. 3.5.4. Ties v. dotted notes

- Example 3.5.4A: This is an incorrect use of a dotted note because the dotted note begins on a weak part of the beat and continues into the next beat-box.

- Remember that notes can cross over beats only when they begin on a strong beat.

- Example 3.5.4B: This is the correct way to write Example 3.5.4A (and Example 3.5.3B). When sustaining a note beginning on a weak beat or weak part of the beat, use a tie.

Example 3.5.3B also illustrated a note being held out by two ties in a row. Indeed, a series of ties can be used to sustain a sound for multiple measures, as shown in Example 3.5.5.

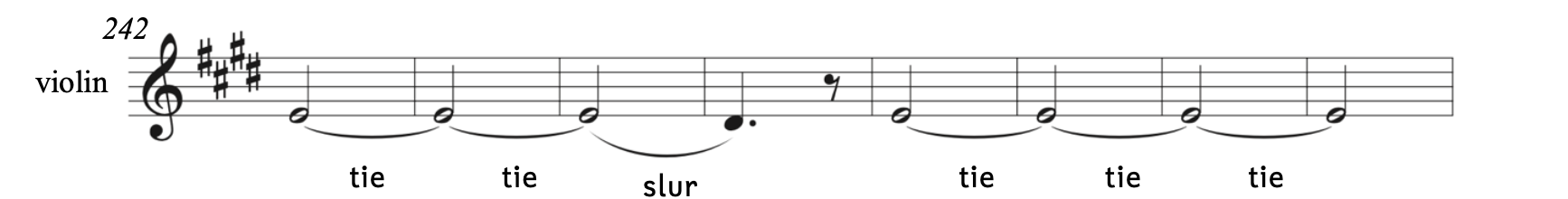

Example 3.5.5. Multiple ties: Mayer[8], Violin Sonata, Op. 19, ii – Scherzo

Every curved line in Example 3.5.5 is a tie except for the one labeled as a slur. The first two ties connect E for three full bars; the last three ties sustain E for four full bars.

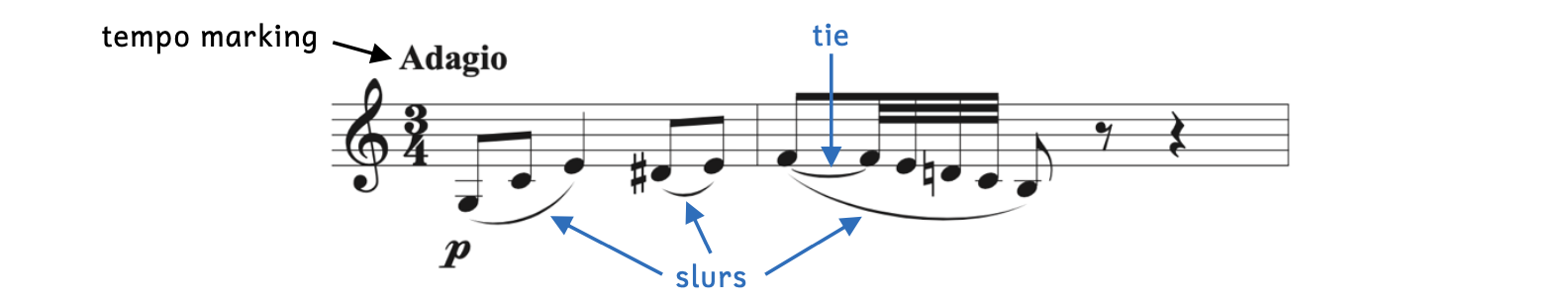

Ties and slurs can occur simultaneously, as seen in Example 3.5.6.

Example 3.5.6. Ties and slurs: Mayer, Violin Sonata, Op. 19, iii – Adagio

In addition to occurring across bar lines, ties can be used instead of dots when a note begins on a strong beat. There is a tie at the start of measure 2. We know it is a tie (and not a slur) because it connects F to F.

- Why wasn’t a dotted note used instead? A dot after an eighth note would equal a sixteenth note. However, this eighth note is tied to a thirty-second note.

- In this case, a dot would be mathematically incorrect so a tie had to be used.

The two rests that conclude Example 3.5.6 are not tied because rests are never tied—only notes are tied. Since rewritten rests imply continued silence, there is no need for ties with rests.

With the exception of the tempo marking (which we will learn about at the end of this chapter), we have learned about many parts of Example 3.5.2.

- There are three slurs, which tell the musician to connect those notes smoothly.

- The time signature is 3/4, which is simple triple. It means there are three beats per measure and the quarter note is equal to one beat.

- Notice how the music is clearly divided into beats.

- In measure 2, the last thirty-second note is not beamed to the last eighth note because the eighth note begins a new beat.

- The example begins piano, meaning that it begins softly.

- There is a D

in measure 1. It is written as D

in measure 1. It is written as D and not its enharmonic equivalent, E

and not its enharmonic equivalent, E , because its goal is to ascend to E. Sharps imply upward motion.

, because its goal is to ascend to E. Sharps imply upward motion. - There is a courtesy accidental in measure 2 (D

). Parentheses are not required for courtesy accidentals.

). Parentheses are not required for courtesy accidentals.

- Although the bar line erases the D

from the previous measure, the natural sign is a reminder that the pitch is D

from the previous measure, the natural sign is a reminder that the pitch is D .

.

- Although the bar line erases the D

Ties

A tie is a curved line that connects two of the same pitches and holds out the note (i.e., the note is sustained and not resounded).

Practice 3.5. Distinguishing Ties from Slurs

Directions:

- Identify and label all slurs and ties in the following examples.

1. Viardot[9], Sonatine for Violin and Piano, i – Allegro

2. Viardot, Sonatine for Violin and Piano, i – Allegro

Click here to watch the tutorial.

3.6 MORE DOTS

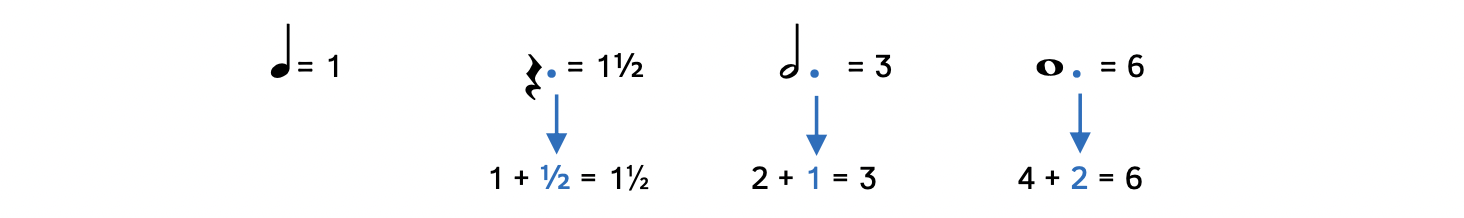

We learned that you can extend the value of a note or rest by half by adding a dot.

Example 3.6.1. Dotted notes and rests

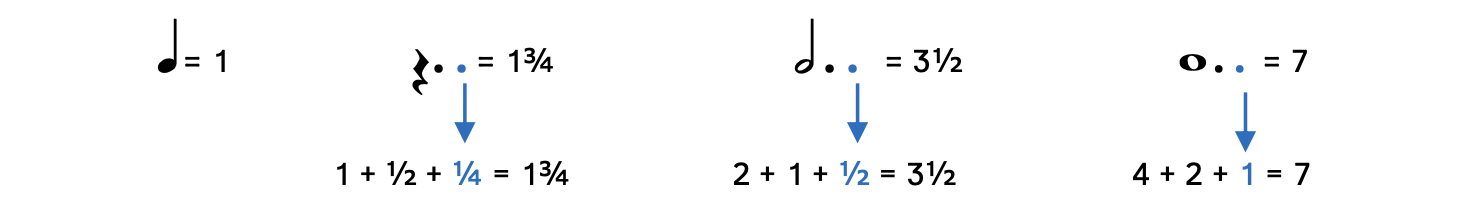

If we add another dot, it becomes a double-dotted note or double-dotted rest and extends the value of a note or rest by half of the dot’s value.

Example 3.6.2. Double-dotted notes and rests

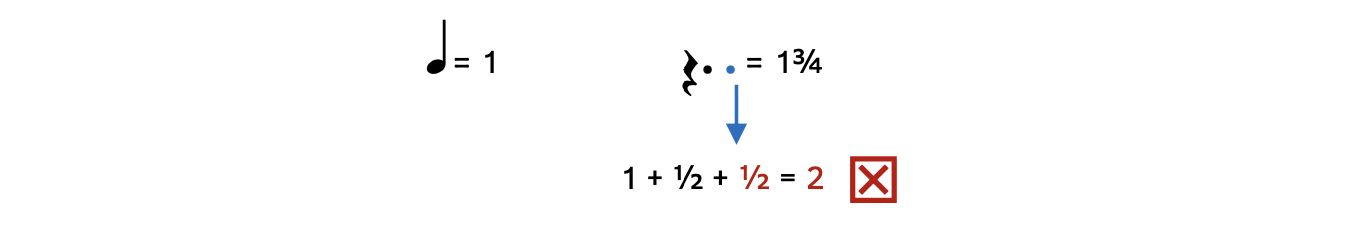

The most common mistake students make is that they add half the value of the note for the second dot, instead of half the value of the first dot.

Example 3.6.3. Incorrect addition of double-dotted note

- If a quarter note is equal to one beat, a quarter rest is equal to one beat.

- The first dot = ½.

- The second dot is equal to half of the first dot, not half of the beat. In Example 3.6.3, another ½ is incorrectly added.

- The correct answer is 1¾ (1 + ½ + ¼).

Example 3.6.4 shows a double-dotted note in context.

Example 3.6.4. Double-dotted notes: Park[10], Violin Sonata, Op. 13, No. 1, i – Andante Maestoso

- In 3/4, the quarter note is worth one beat. The eighth note is worth ½ beat, the first dot is worth ¼ beat, and the second dot is worth one-eighth of a beat.

- ½ + ¼ + one-eighth = seven-eighth of a beat. A note value of one-eighth of one beat is required to fill one beat.

- If a quarter note is worth one beat, then an eighth note is worth ½ beat, a sixteenth note is worth ¼ beat, and a thirty-second note is worth one-eighth beat. Therefore, a thirty-second note is beamed to the double-dotted eighth note to complete each beat in measure 1.

Example 3.6.4 also includes several things we have already learned.

- The music begins forte and on the “and” of measure 2, the dynamics suddenly drop to piano.

- The last two notes are slurred.

- There is no bar line at the end because the example stops in the middle of a measure.

Dotted notes are extremely common, double-dotted notes are less common, and triple-dotted notes/rests are even less common.

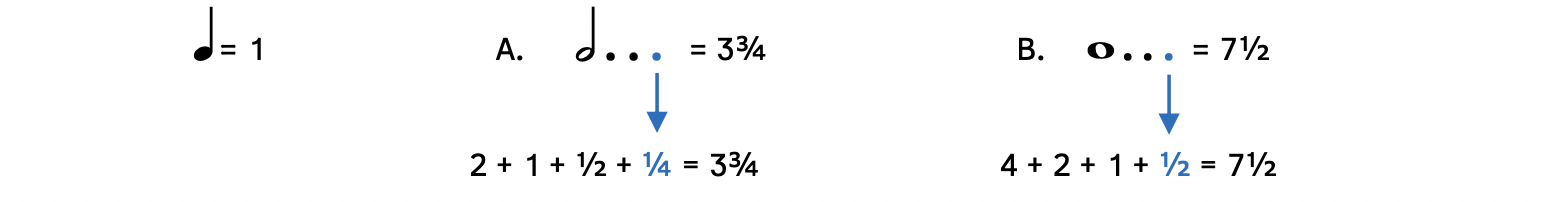

Example 3.6.5. Triple-dotted notes

- Example 3.6.5A: If a quarter note equals one beat, a half note = 2.

- The first dot adds half of 2 = 1.

- The second dot adds half of 1 = ½.

- The third dot adds half of ½ = ¼.

- Therefore, a triple dotted half note is worth 3¾.

- Example 3.6.5B: If a quarter note equals one beat, a whole note = 4.

- The first dot adds half of 4 = 2.

- The second dot adds half of 2 = 1.

- The third dot adds half of 1 = ½.

- Therefore, a triple dotted whole note is worth 7½.

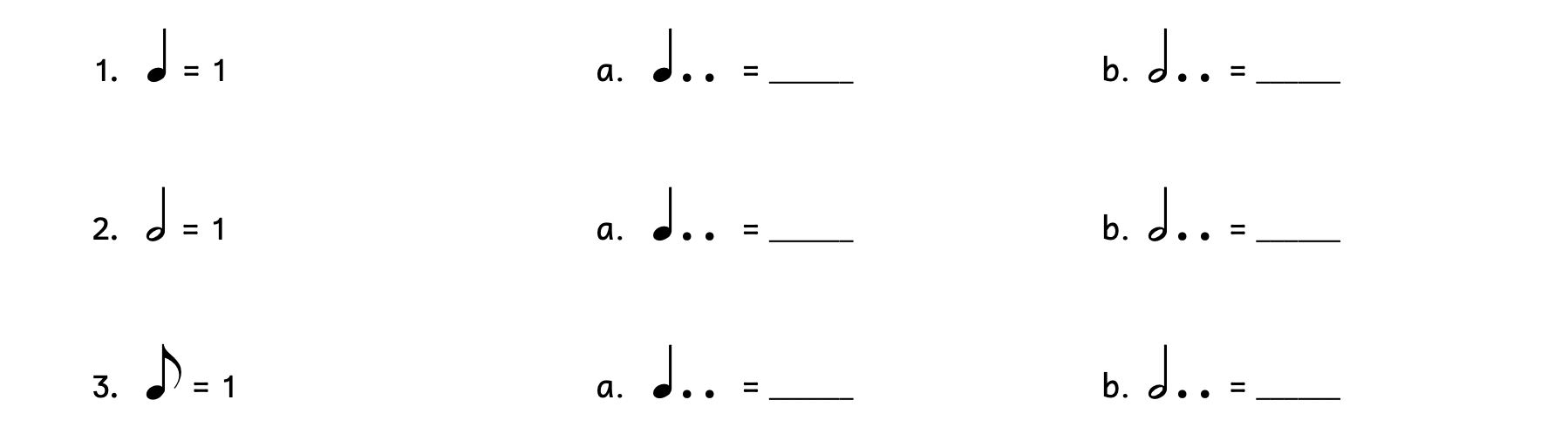

Practice 3.6. Calculating Double-Dotted Note Values

Directions: Based on the given note that equals one beat, write the value of the other notes. For samples, see Example 3.6.2.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2a) 7/8

3a) 31/2

3.7 ANACRUSIS

We learned that a simple meter’s time signature tells us how many beats there are per measure and what type of note gets one beat. However, sometimes there seems to be a mistake at the start of the piece: not enough beats.

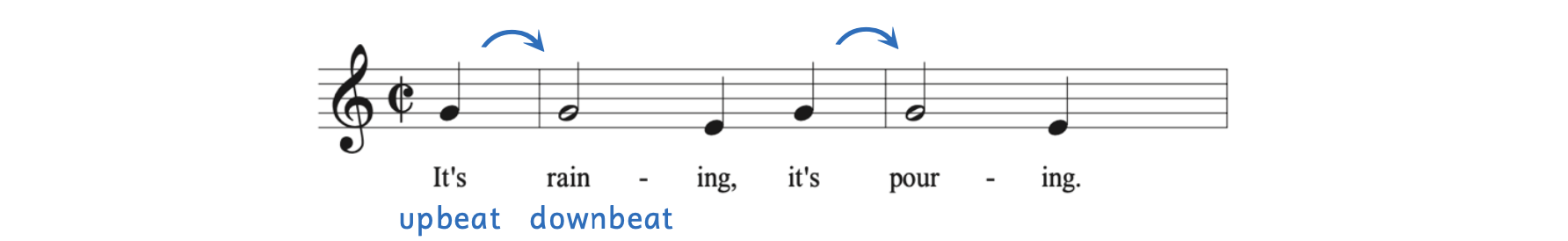

Example 3.7.1. Anacrusis: “It’s Raining, It’s Pouring”

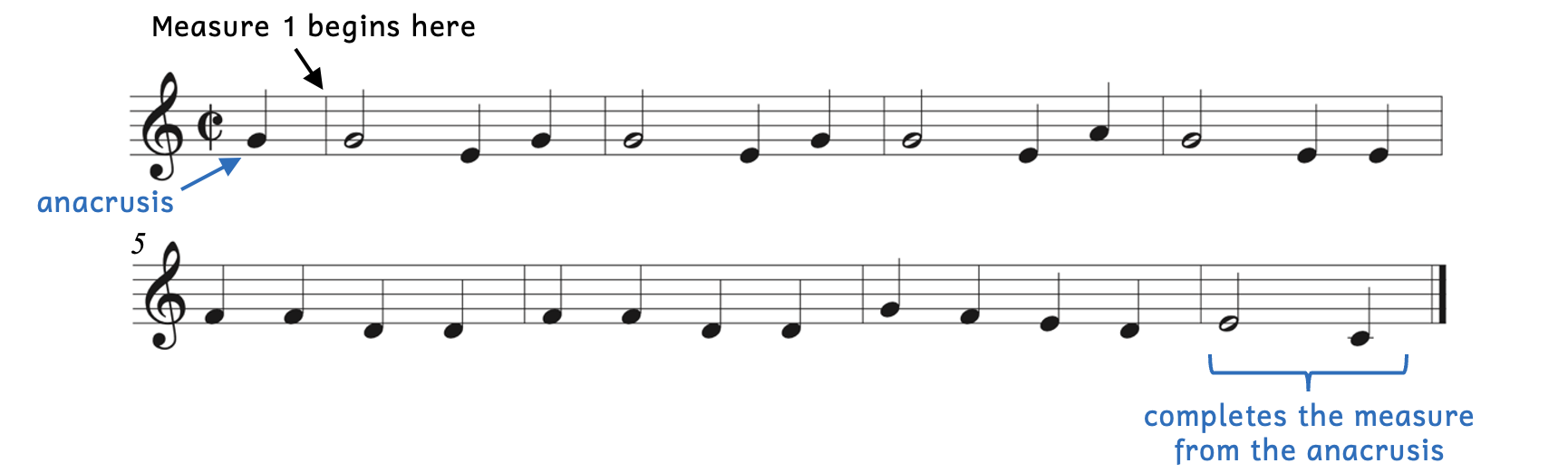

In “It’s Raining, It’s Pouring,” the first measure seems to have only one quarter note. When a piece of music begins with less than its full measure, it is not considered a measure but is an anacrusis, (or pickup or upbeat). The anacrusis combines with the last measure of the piece, which is also an incomplete measure, to fill a complete measure.

Notice that measure 1 does not start until after the anacrusis because the anacrusis is an incomplete measure. The second system begins with measure 5, not measure 6.

In Example 3.7.1, the time signature is cut time, which means there are two beats per measure and the half note gets one beat. The anacrusis is one quarter note, which is worth ½ beat. This means 1½ beats are required to fill the bar. We look to the last measure, which has a half note and quarter note, which is equal to 1½ beats in cut time. Therefore, in combination with the anacrusis, the last measure completes one full measure.

As mentioned, other names for the anacrusis include the pickup or upbeat. These terms may help you understand how the anacrusis is to be performed. Recall that the strongest beat in any measure is beat one, also known as the downbeat. The upbeat leads into the downbeat. In other words, the anacrusis is not to be performed as the last note of a measure, but rather, the note leading into the following downbeat.

Example 3.7.2. Upbeat: “It’s Raining, It’s Pouring”

When you sing Example 3.7.2, “It’s” is connected to “raining”: “It’s raining.” You do not sing “raining, it’s.” Sometimes, students mistakenly see a bar line as a symbol for when music breaks or pauses. However, the bar line is simply a way to organize beats. The downbeat is still the strongest beat, but the preceding pickup connects to the downbeat. We also saw similar upbeats in Strauss’s “The Blue Danube Waltz” in Example 3.1.3.

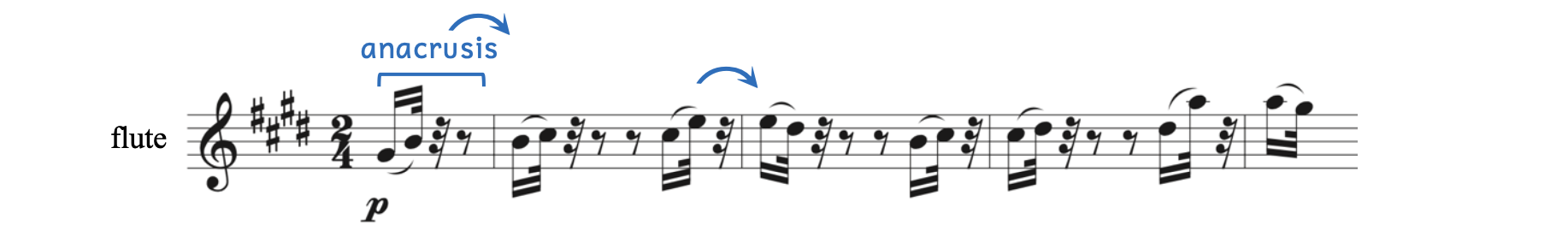

The anacrusis can be more than one note. The anacrusis in Example 3.7.3 contains two notes, but is only worth one beat. Because one beat does not fill the measure, this example opens with an anacrusis.

Example 3.7.3. Anacrusis: Ponchielli[11], “Dance of the Hours,” La Giaconda

Even though there are rests in the anacrusis, can you still hear how the upbeat connects to the downbeat?

The anacrusis can also be more than one beat. The three notes in the anacrusis in Example 3.7.4 are equal to 1½ beats.

Example 3.7.4. Anacrusis: Rossini[12], The Barber of Seville, Overture

Even with three notes spanning over one beat, the anacrusis still leads into the downbeat.

Anacrusis

- An anacrusis is an incomplete measure that begins a piece of music.

- The measure after the anacrusis is measure 1.

- The anacrusis and the final measure equal one complete measure.

- When performing an anacrusis, be sure that it leads into the following downbeat.

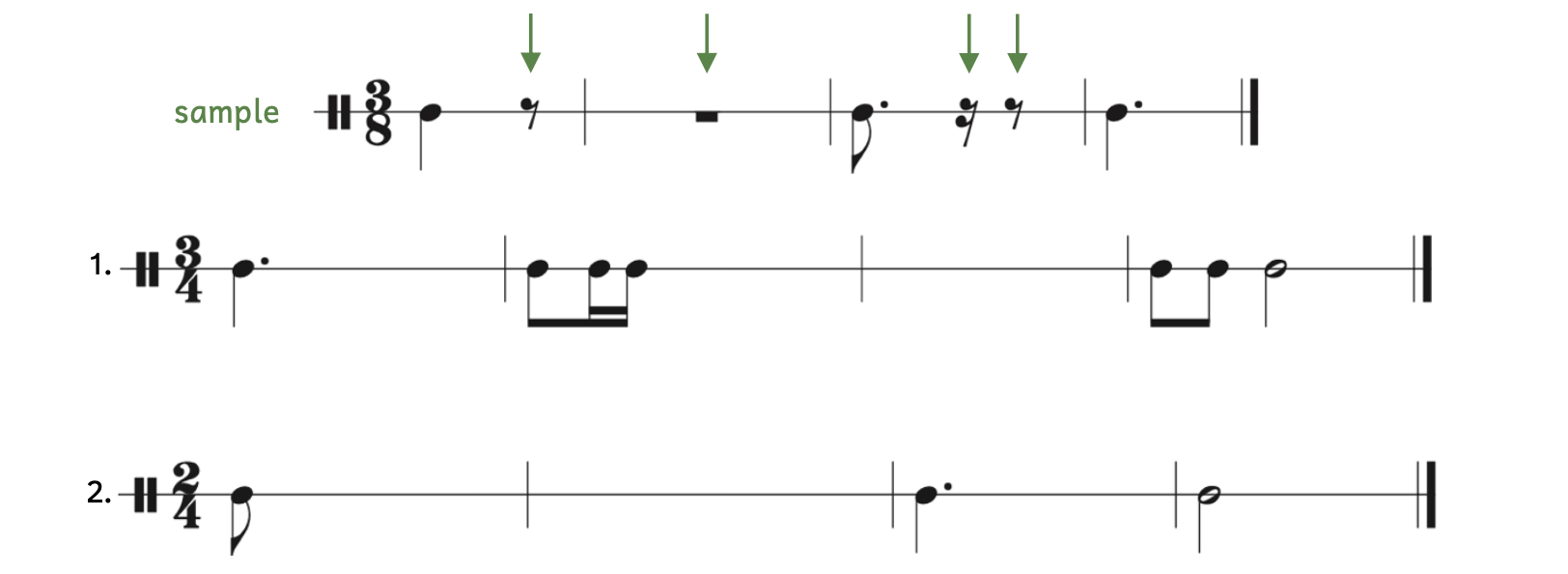

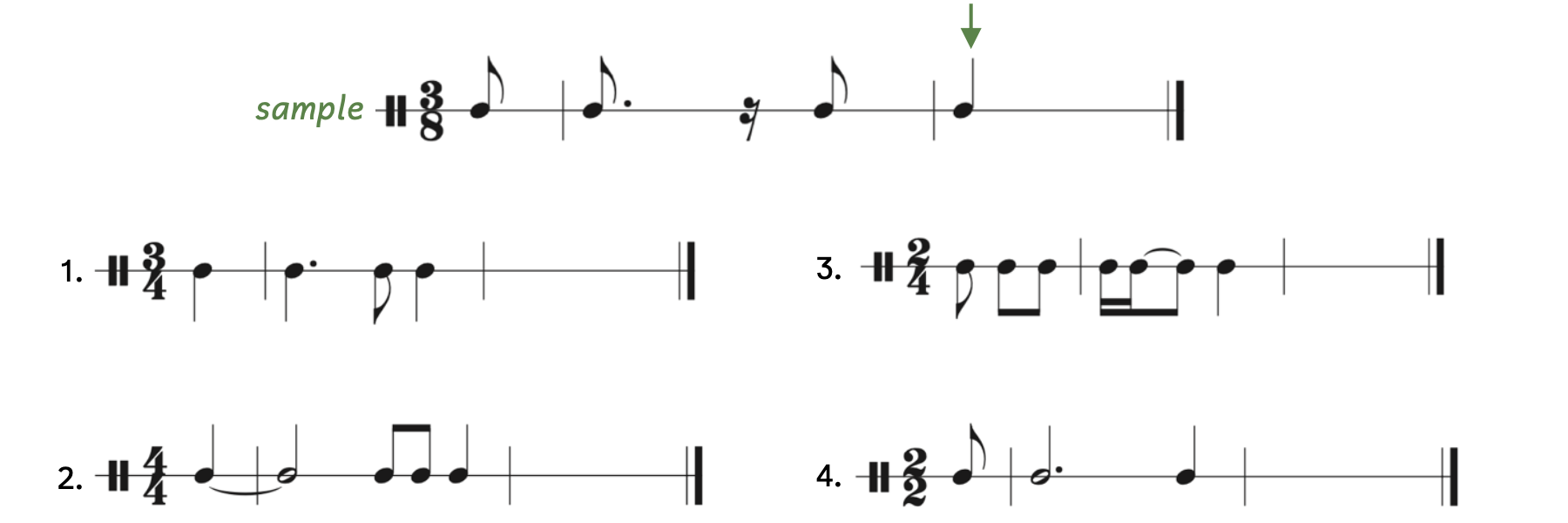

Practice 3.7. Balancing an Anacrusis in the Final Measure

Directions:

- Complete the last measure with the fewest notes possible.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

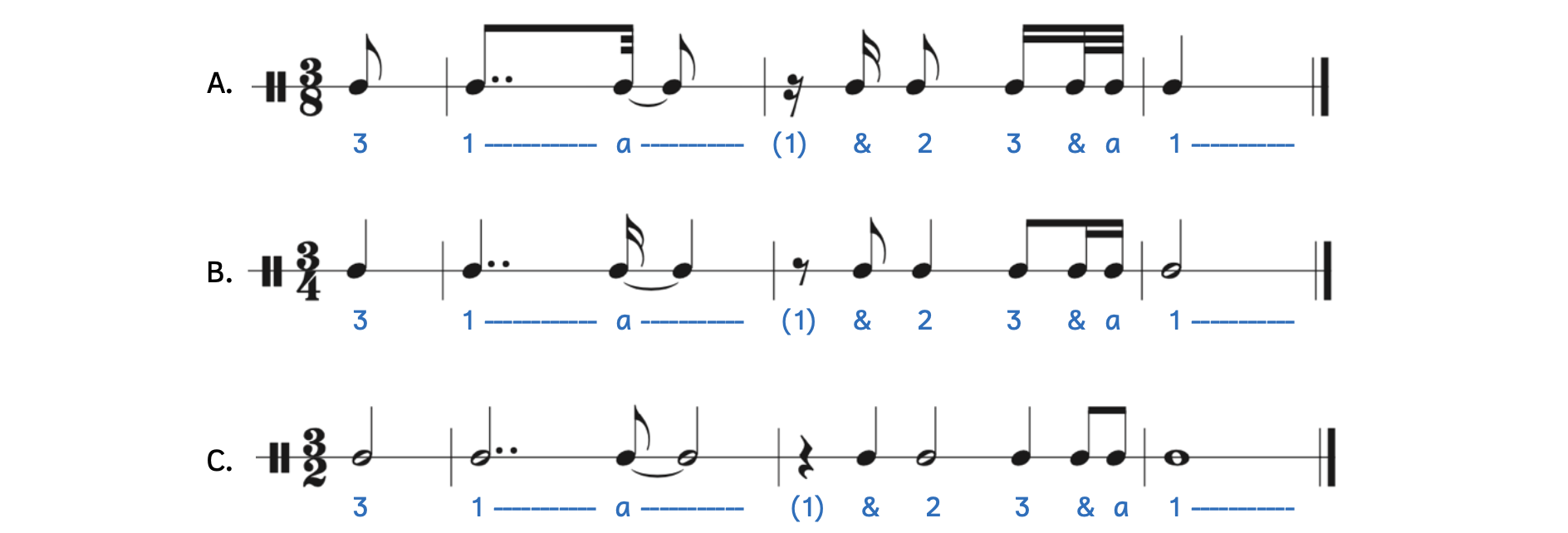

3.8 TRANSPOSITION: RHYTHMIC

Some students are most comfortable writing and reading music where the quarter note is the beat. When the beat is an eighth note or half note, they sometimes struggle. One strategy those students can utilize is using transposition, which is when you change the music by the same proportion. Rhythmic transposition is when you rewrite the notes with the same rhythmic syllables but a different note gets one beat. Compare the examples below.

Example 3.8. Rhythmic transposition

We know all the notes in Examples 3.8A, B, and C are proportionally equal because the rhythm syllables are exactly the same.

- Example 3.8A: The first measure may challenge some students because of the double-dotted eighth note followed by a tied thirty-second note.

- Meanwhile, in Example 3.8B, the quarter note clearly places beat 3 and can be used to make Example 3.8A easier to understand.

- Example 3.8C: Due to the lack of beaming, the second measure may challenge some students as the beats are harder to find.

- Meanwhile, in Example 3.8B, the beaming makes the beats clearer.

Rhythmic transposition may be a strategy utilized in aural training if you are asked to write a rhythmic dictation for a time signature you find challenging. There are two steps when writing rhythmic transpositions.

- Write the rhythmic dictation so a quarter note gets the beat.

- Based on the ratio of the two note values, convert all notes by the same proportion.

- For example, if the time signature is 3/8, you would need to change all the note values in your rhythmic dictation by half since an eighth-note beat is worth half a quarter-note beat.

Rhythmic Transposition

When transposing rhythms, compare note values of the beats and apply that same proportion to the new time signature.

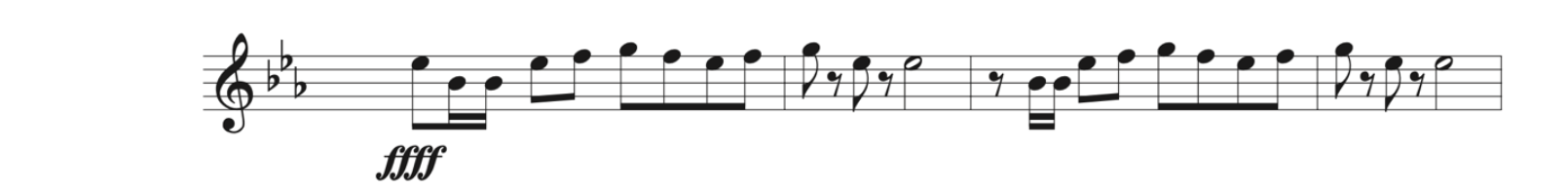

Practice 3.8. Transposing Rhythms Across Time Signatures

Directions:

- Transpose the rhythms into the given time signatures. For a sample, see Example 3.8.

- Keep all pitches, articulations, and dynamics.

1. Tchaikovsky, “Russian Dance,” The Nutcracker

2. Bach, “Crucifixus,” Mass in B Minor, BWV 232

Click here to watch the tutorial.

3.9 TEMPO MARKINGS

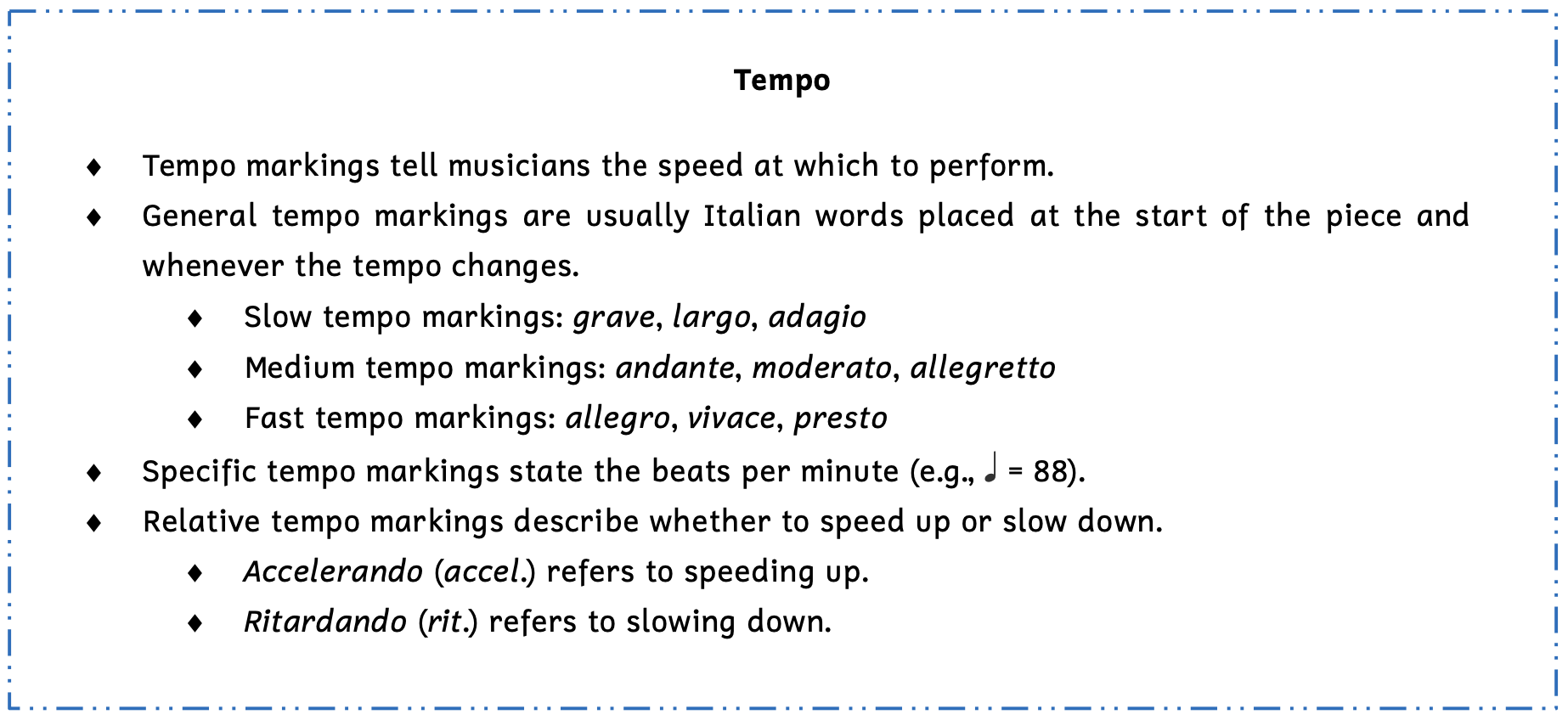

In Chapter 1, we learned about articulation marks: symbols that tell musicians how to perform specific notes. In Chapter 2, we learned about dynamics: symbols that tell musicians at what volume (how soft or how loud) to perform specific sections. Since Chapter 3 is about meter and rhythm, this final section will focus on tempo, the speed at which music is performed. Tempo markings tell the musician how fast or slow to perform. There are three ways to convey the desired speed:

- General tempo marking: Often an Italian term (e.g., allegro) that give us a general sense of how fast or slow to perform.

- Specific tempo marking: Beats per minute and/or metronome mark that tells us exactly how fast or slow to perform.

- Relative tempo marking: Usually Italian terms (e.g., ritardando) that say whether to slow down or speed up.

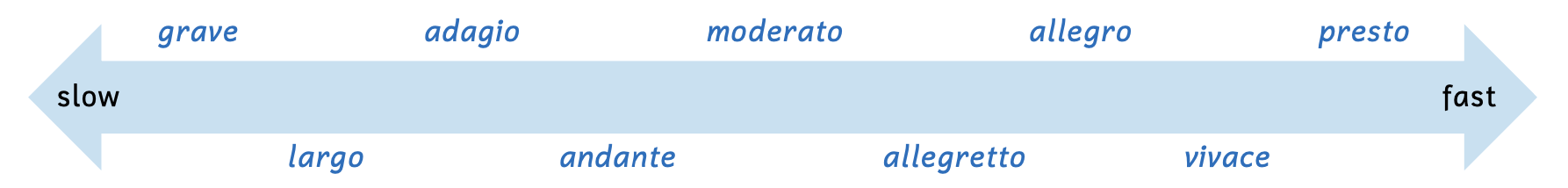

General tempo markings are not always in Italian, but often are. These tempo markings are found at the beginning of the piece, and can also be found whenever the music changes tempo. There are too many different tempo marks to name here; however, Example 3.9.1 shows the most common ones.

Example 3.9.1. Tempo markings

The spectrum above shows various tempo markings from the slowest to the fastest. Just as we thought of piano as soft and forte as loud, we can simply think of adagio as slow and allegro as fast. These are considered general tempo markings because one musician’s interpretation of allegretto may be quite different than another’s. However, the difference between adagio and allegro should be clear.

Since the details of articulation, dynamics, and tempo are outside the scope of this theory book, it is recommended that you take note whenever you encounter a new term. We already encountered two examples of general tempo marks in this chapter.

Example 3.9.2. Tempo marking: Mayer, Violin Sonata, Op. 19, iii – Adagio

In Example 3.9.2, the tempo marking is Adagio, which means slowly. Notice that in the name of the piece, it ends with the movement number followed by the tempo marking. This technique is also used when listing movements in program notes.

Dynamics used mezzo– and –issimo to imply “moderate” and “more.” Tempo markings use moderato and molto to mean the same thing. For example, allegro moderato is not quite as quick as allegro while molto vivace is very fast. Composers can also use words such as prestissimo, which is even faster than presto. Other words may be used to supplement tempo markings, such as maestoso.

Example 3.9.3. Tempo marking: Park, Violin Sonata, Op. 13, No. 1, i – Andante Maestoso

In Example 3.9.3, the tempo marking is Andante Maestoso, which means majestically slow.

Specific tempo markings say how fast or slow the beat is by explicitly displaying how many beats per minute or by using metronome marks. For example, the music may say [quarter note] = 152, where there are 152 quarter notes per minute.

The specific tempo marking can also say M.M. [quarter note] = 152. M.M. stands for Mälzel’s Metronome. The music can even use both a general and specific tempo marking (e.g., Allegro [quarter note] = 152).

Example 3.9.4. Specific tempo marking: Röntgen-Maier[13], Violin Sonata in B Minor, iii – Allegro molto vivace

- Both a general and specific tempo marking are used in the score, but only the general tempo marking is used in the title of the movement.

- The general tempo marking uses more detailed words: Allegro molto vivace.

- To highlight that this movement should sound fast, Röntgen-Maier writes the beats per minute as a half note, rather than a quarter note, which is what should get the beat in 2/4.[14]

- Notice the use of slurs versus ties in measure 7.

- Notice the use of an accent mark versus crescendo/diminuendo marks in measure 7.

Relative tempo marks are similar to the gradual dynamics we learned: crescendo and diminuendo. For tempo, the most common terms are accelerando (speed up) and ritardando (slow down).

Example 3.9.5. Relative tempo marks: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”

- The tempo is moderato, or a quarter-note beat equaling 92.

- In measure 10, the music becomes much faster (molto accelerando).

- At measure 11, the original tempo resumes (a Tempo).

- On beat 3 of measure 11, the music begins to slow down (ritardando) and get softer (diminuendo) until the end (al fine).

Practice 3.9A. Ordering Tempo Markings

Directions:

- Arrange the following tempo markings from slowest to fastest by writing their name onto the spectrum arrow below.

- allegro

- allegretto

- largo

- andante

- prestissimo

- presto

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Practice 3.9B. Choosing Tempo Markings

Directions:

- Listen to the following examples and write an appropriate tempo marking.

1. Rimsky-Korsakov[15], Flight of the Bumblebee

2. Verdi[16], “La donna è mobile,” Rigoletto, Act III

3. Bach, Air on a G String

4. Brahms[17], Hungarian Dance No. 5

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) Allegretto (moderato acceptable)

3) Adagio (andante acceptable)

4) Allegro (allegretto acceptable)

SUMMARY

-

-

- Meter is when beats are organized into regular groups of two, three or four, and where the downbeat always has the strongest accent. [3.1]

- The time signature is placed at the start of a piece of music after the clef. For simple meters, the numbers of the time signature refer to specific things. [3.2]

- The top number means how many beats per measure. It can be 2, 3, or 4.

- The bottom number means what type of note gets one beat. It is usually 2, 4, or 8, but can technically be any note value (e.g., 16).

- Common time is the same as 4/4.

- Cut time is the same as 2/2.

- We combine beat and meter classifications to describe time signatures (e.g., simple triple). [3.3]

- The whole rest literally means a whole measure of rest except in one situation. [3.4]

- Ties are curved lines that connect two of the same pitch and represent that the note should be held out and not resounded. [3.5]

- A dot after a note or rest means to add half the value of that note or rest. With each additional dot, add half the value of the dot. [3.6]

- An anacrusis (or upbeat or pickup) is an incomplete measure that begins the piece. The last measure is also incomplete and combined with the anacrusis, creates a complete measure. [3.7]

- The measure after the anacrusis is measure 1.

- Rhythmic transposition is when you reinterpret a time signature in another time signature where the beat differs. [3.8]

- Rhythmic transposition can be utilized in aural training.

- Tempo markings tell musicians how fast or slow to perform. [3.9]

- General tempo markings are usually in Italian and give a general sense of how fast or slow to perform.

- Specific tempo markings show the beats per minute and tells musicians exactly how fast or slow to perform.

- Relative tempo markings are usually in Italian and say whether to speed up (acclerando) or slow down (ritardando).

-

TERMS

-

-

- accelerando

- anacrusis

- beat classification

- common time

- cut time

- double-dotted note/rest

- downbeat

- meter

- meter classification

- pickup

- ritardando

- rhythmic transposition

- simple meter

- tempo

- tempo markings

- grave

- largo

- adagio

- andante

- moderato

- allegretto

- allegro

- vivace

- presto

- tie

- time signature

- transposition

- triple-dotted note/rest

- upbeat

-

- John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) was an American composer known as "The March King." ↵

- Johann Strauss II (1825-1899) was an Austrian composer known as "The Waltz King." ↵

- Stephen C. Foster (1826-1864) was an American composer known as "The Father of American Music." ↵

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) was a Russian composer. ↵

- Louise Bertin (1805-1877) was a French composer and poet. ↵

- Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was a German composer. ↵

- Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) was a British composer. ↵

- Emilie Mayer (1812-1883) was a German composer. ↵

- Pauline Viardot (1821-1910) was a French composer and mezzo-soprano. ↵

- Maria Hester Reynolds Park (1760-1813) was an English composer. ↵

- Amilcare Ponchielli (1834-1886) was an Italian composer. ↵

- Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) was an Italian composer. ↵

- Amanda Röntgen-Maier (1853-1894) was a Swedish violinist and composer. ↵

- Although this example begins in measure 5, the time signature and tempo marking have been added for convenience. ↵

- Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) was a Russian composer. ↵

- Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) was an Italian composer. ↵

- Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was a German composer. ↵

The accented first beat of a measure.

Regularly occurring pattern of strong beats and weak beats.

Meter where the beat evenly divides into two.

Two numbers at the beginning of a piece of music that says what gets one beat and how many beats per measure.

Simple or compound.

Duple, triple, or quadruple.

A curved line that connects two of the same pitches and holds out the note (i.e., the note is sustained and not resounded).

A note with two dots following it. The first dot represents half the value of the note, while the second dot represents half the value of the first dot.

A rest with two dots following it. The first dot represents half the value of the rest, while the second dot represents half the value of the first dot.

Notes and rests that have three dots. Each dot is worth half the value of the previous note or dot.

Incomplete measure that begins a piece. It is not considered measure 1. Also known as an upbeat or pickup.

Incomplete measure that begins a piece. It is not considered measure 1. Also known as an anacrusis or upbeat.

Incomplete measure that begins a piece. It is not considered measure 1. Also known as an anacrusis or pickup.

The act of changing all notes equally by the same proportion.

Changing all note and rest values equally by the same proportion.

The speed at which music is performed.

Markings that tell musicians how fast or slow to perform.

Speed up.

Slow down.

Symbol that looks like an upper-case C that also means 4/4.

Time signature that looks like an upper-case C with a vertical line running through it; same as 2/2.