10 Transposing Instruments

Now that you have learned about intervals, we will learn about how to read and write for transposing instruments—instruments whose written pitch differs from their concert pitch.[1] We will also learn about the four different types of texture.

10.1 INTRODUCTION

The instruments we have seen in musical examples until now have all been instruments in C (or C instruments). For instruments in C, the note musicians see and perform is the same note we hear. Some instruments in C include the piano, all strings (e.g., violin, viola, and cello), flutes, oboes, bassoons, and percussion instruments. When you play a C on the violin, we hear a C.

One version of Farrenc’s Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello is written for three C instruments (Example 10.1.1).

Example 10.1.1. Instruments in C: Farrenc[2], Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 44, iii – Minuetto. Allegro

Because the violin, cello, and piano are instruments in C, every note you see (called written pitch) is the same as what you hear (called concert pitch).

Farrenc composed the trio for either violin or clarinet. Now observe Example 10.1.2. What do you notice about the key signatures of the different instruments?

Example 10.1.2. Key signatures: Farrenc, Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 44, iii – Minuetto. Allegro

The key signature for the clarinet is different. The clarinet’s key signature has one flat, while the cello’s and piano’s key signatures have three flats. How is this possible?

Now look at the clarinet’s opening pitch compared to the pitches occurring at the same time in the cello and piano.

- The clarinet’s pitch is A.

- The cello’s pitches are E-flat, B-flat, and G.

- The piano’s pitches are E-flat, G, and B-flat.

Notice that the clarinet’s A is unlike the other notes. Indeed, if you were to hold out E-flat, G, and B-flat, then play A on the piano, it would sound out of place. Listen to what this would sound like:

The reason why the clarinet’s key signature and pitch do not match the other instruments is because the clarinet in B-flat is not an instrument in C, but rather, a transposing instrument. Transposing instruments are those whose music on the printed page (written pitch) and actual sound (concert pitch) are different.

Refer back to Example 10.1.2. Because the clarinet in B-flat is a transposing instrument, the clarinet’s A does not sound like A: it sounds like G. This time, compare this G to the notes in the cello and piano: E-flat, G, and B-flat. The clarinet’s G now fits in with the other instruments. Now listen to what this would sound like:

In addition, if we compare the clarinet’s part in Example 10.1.2 to the violin’s part in Example 10.1.1, we see that the two instruments are playing the same concert pitches. Both begin on G4.

You may wonder why there are transposing instruments. Part of it has to do with history, but much has to do with ease for performers.

- When instrumentalists learn a fingering for an instrument, they can transfer the same fingering to other instruments in its family.

- For example, someone playing the clarinet in B-flat would generally use the same fingerings when playing not only the clarinet in A, but also the clarinet in C, the clarinet in D, and the clarinet in E-flat. Without transposing instruments, clarinetists would be expected to learn different fingerings for each instrument. Imagine how difficult it would be to play four types of pianos where the pattern of white keys and black keys differed on each one.

- Using transposing instruments lessens the need for pitches on the extreme ends of a staff—it reduces the necessity for multiple ledger lines. This is similar to using an appropriate clef for how high or low notes sound.

Transposing instruments do not create any extra work for the performers: musicians play what they see, but a different sound comes out. However, transposing instruments create extra work for the analyst (you) as well as the composer (you).

Instruments in C Versus Transposing Instruments

- Instruments in C: Instruments in which the note you see (written pitch) is the note you hear (concert pitch).

- Transposing instruments: Instruments in which the note you see is not the note you hear.

10.2 READING TRANSPOSING INSTRUMENTS

Now that we know what transposing instruments are, we must learn how to interpret them. For this, we use our knowledge of intervals.

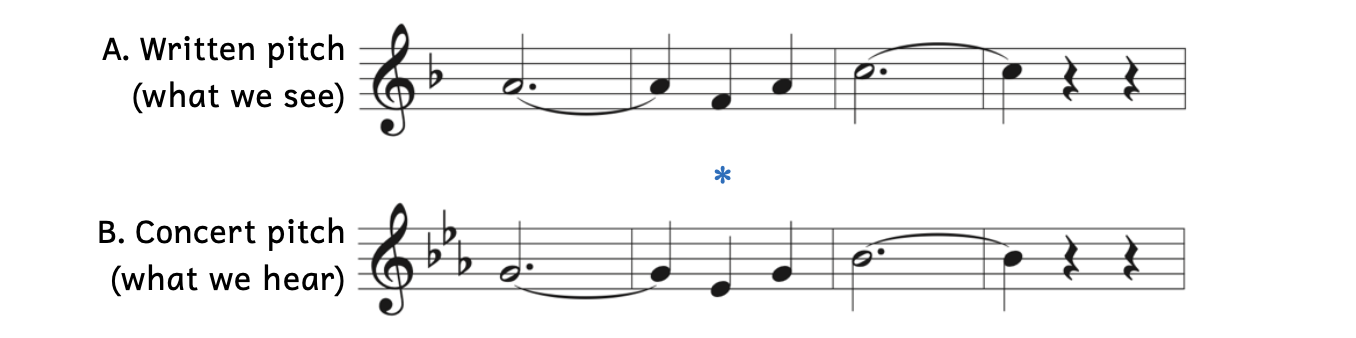

If a clarinet in B-flat plays C4, you will hear B-flat3 (and not C4). This means that for every pitch in the clarinet’s part, you will hear a note that is a major second lower. Returning to the Farrenc trio, we can now put the clarinet’s concert pitches below the written pitches to compare.

Example 10.2.1. Written pitch versus concert pitch for the clarinet in B-flat from Example 10.1.2

Every concert pitch is a major second lower than every written pitch. Every pitch is also the same as the violin’s part from Example 10.1.1, which is an instrument in C.

You cannot use enharmonic equivalents for transposing instruments. For example, the pitch marked with an asterisk in Example 10.2.1A is an F. A major second below F is E-flat (shown in Example 10.2.1B) and not D-sharp. This is because the interval is a major second below and as we learned with intervals, the number must be precise. D-sharp is a diminished third below F. Moreover, recall that the other instruments were playing E-flat, G, and B-flat: D-sharp does not make sense with these notes.

To help us figure out concert pitches for transposing instruments, we can use a transposing instrument chart template (Example 10.2.2).

Example 10.2.2. Transposing instrument chart template

- Example 10.2.2A:

- In this row, you write the note that you see, also known as the written pitch.

- Always write “C” in the first box because transposing instruments are named based on the note that sounds when they play C.

- Hint: “See” and “C” are homophones–C will always be in the first row of the first column.

- Example 10.2.2B:

- In this row, you write the note that you hear, also known as the concert pitch.

- In the second column, always write the key of the transposing instrument. For example, for a trumpet in B-flat, write “B-flat” and for a horn in F, write “F.”

- The concert pitch is the note you hear. A trumpet in B-flat is called a trumpet in B-flat because when they play C, you hear B-flat.

- Example 10.2.2 Column 2:

- Figure out the interval from C down to the concert pitch and write the interval in the box.

- Most instruments sound lower than their written pitch. Although you can use the inversion and flip the descending interval into an ascending one, it is better (and correct) to get into the right habit of writing the precise transposition.

- Later, we will learn about instruments whose concert pitch is higher than their written pitch.

Example 10.2.3 shows why a transposing instrument chart is not necessary for instruments in C, such as the flute, cello, or piano.

Example 10.2.3. Transposing instrument chart for instruments in C

Because instruments in C have the same concert pitch and written pitch, there is no need to use a transposing instrument chart. Now we will create a transposing instrument chart for a clarinet in B-flat (Example 10.2.4).

Example 10.2.4. Transposing instrument chart for clarinet in B-flat

- Example 10.2.4A:

- In the top column, always write “C” because it refers to the note you see and the note C. This is easy to remember because of the homophones.

- In the bottom of this column, always write the key of the transposing instrument because this is the note we hear when the instrument plays C. Since the instrument is a clarinet in B-flat, we write “B-flat” in this box.

- Example 10.2.4B:

- Figure out the relationship from C to B-flat to find the interval transposition: B-flat is a major second lower than C. Write “down M2” in this box.

- Although B-flat is also a minor seventh above C, the sound of the clarinet in B-flat is a major second below C. It is best to learn the exact transpositions of the most common instruments. If it helps, write C4 in the first box and B-flat3 in the second box.

- A shortcut to find a major second lower is that the concert pitch sounds a whole step lower. Just be aware that it must be a major second and not a diminished third (or augmented unison).

- Figure out the relationship from C to B-flat to find the interval transposition: B-flat is a major second lower than C. Write “down M2” in this box.

- Example 10.2.4C:

- In this column, it shows that you see a B-flat in the clarinet’s part. Because the clarinet in B-flat sounds a major second lower, the note you would hear is an A-flat.

- This is where students most commonly make an error: They will accidentally think that if a clarinet in B-flat plays B-flat, you hear a C. Remember to always keep C in the “See (C)” column when creating the template.

- Example 10.2.4D:

- In this column, it shows that you see an E in the clarinet’s part. Because the clarinet in B-flat sounds a major second lower, the note you would hear is a D.

- Example 10.2.4E:

- In this column, it shows that you see a G-sharp in the clarinet’s part. Because the clarinet in B-flat sounds a major second lower, the note you would hear is an F-sharp (and not a G-flat).

For all transposing instruments, the instrument’s name tells you the key of the instrument. For example, in addition to the clarinet in B-flat, there is also a clarinet in A. Compare the transposing instrument chart for the clarinet in B-flat (Example 10.2.4) to the clarinet in A (Example 10.2.5).

Example 10.2.5. Transposing instrument chart for the clarinet in A

- Example 10.2.5A:

- Next to “See (C),” write “C” as always.

- Next to “Hear,” write the name of the transposing instrument. For a clarinet in A, you would write “A” under the “Hear” column.

- Example 10.2.5B:

- From these two notes, figure out the relationship to determine the interval transposition: A is a minor third below C.

- Although A is also a major sixth above C, the sound of the clarinet in A is a minor third below C. It is best to learn how to identify descending intervals quickly. If it helps, write C4 in the first box and B-flat3 in the second box.

- A shortcut for a minor third lower is that it is the relative minor.

- From these two notes, figure out the relationship to determine the interval transposition: A is a minor third below C.

- Example 10.2.5C:

- In this column, it shows that you see a B-flat in the clarinet in A’s part. Because the clarinet in A sounds a minor third lower, the note you would hear is a G.

- Example 10.2.5D:

- In this column, it shows that you see an E in the clarinet in A’s part. Because the clarinet in A sounds a minor third lower, the note you would hear is a C-sharp.

- Example 10.2.5E:

- In this row, it shows that you see a G-sharp in the clarinet in A’s part. Because the clarinet in A sounds a minor third lower, the note you would hear is an E-sharp.

- Once again, you cannot use enharmonic equivalents for transposing instruments. No matter how much you think writing F is easier or better than writing E-sharp, F would be incorrect because it is not a minor third below G-sharp but instead an augmented second.

There are many transposing instruments, but as a music theory textbook, we cannot cover each one in detail. Instead, this chapter will help you with the steps to finding the concert pitches for instruments based on their name (e.g., saxophone in E-flat). As already mentioned, although there are some transposing instruments whose concert pitches sound higher than their written pitches, the concert pitches of the most common instruments sound lower. Example 10.2.6 shows several of the most common transposing instruments in addition to the clarinet in B-flat.

Example 10.2.6. Other common transposing instruments

- Example 10.2.6A:

- Like the clarinet, there are different types of trumpets. Also like the clarinet, the trumpet in B-flat is the most common one. If you see “trumpet” without a key following its name, you can assume that it refers to a trumpet in B-flat.

- The concert pitch of the trumpet sounds a major second below the written pitch.

- Example 10.2.6B:

- When you only see “saxophone,” it is assumed to be the alto saxophone in E-flat.

- The concert pitch of the saxophone sounds a major sixth below the written pitch.

- Example 10.2.6C:

- When you only see “horn,” it is assumed to be the horn in F.

- The concert pitch of the horn sounds a perfect fifth below the written pitch.

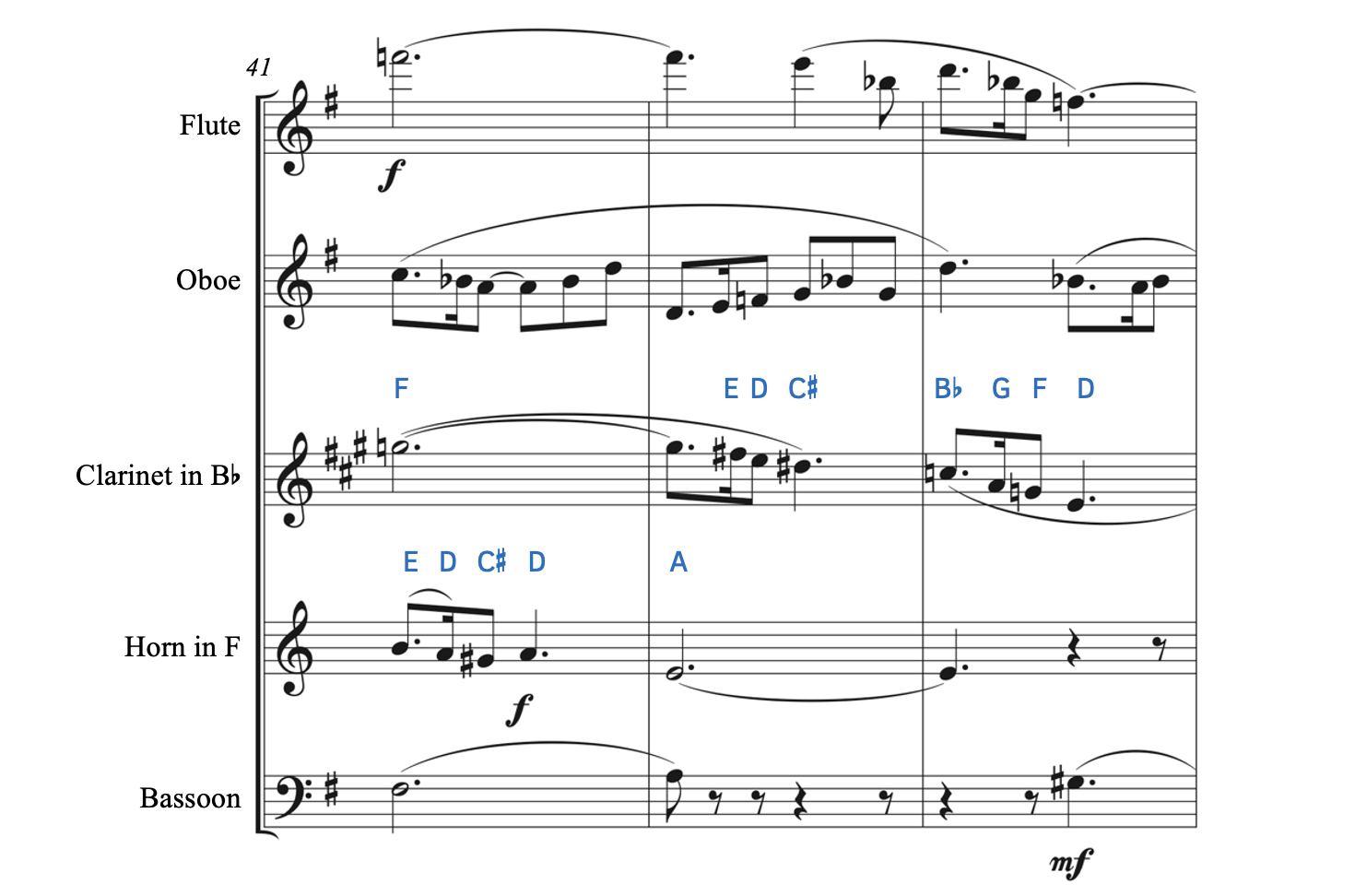

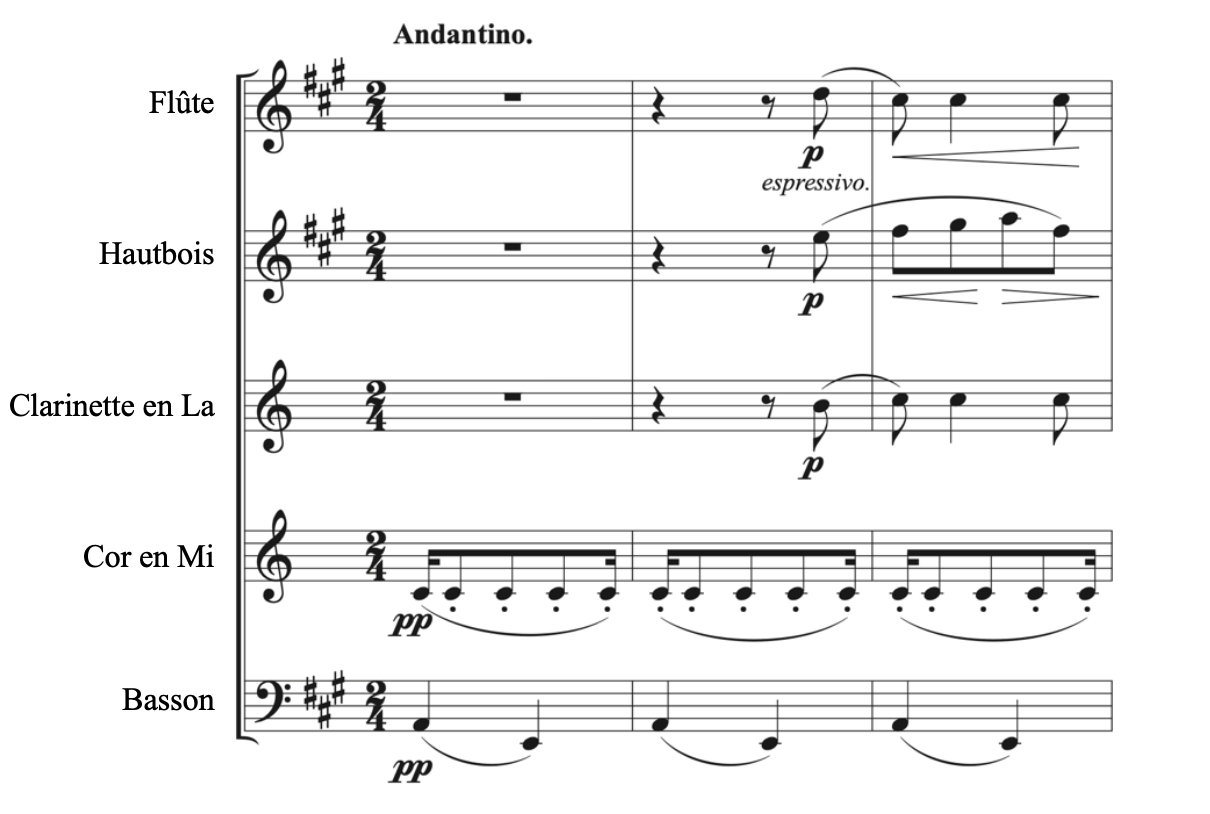

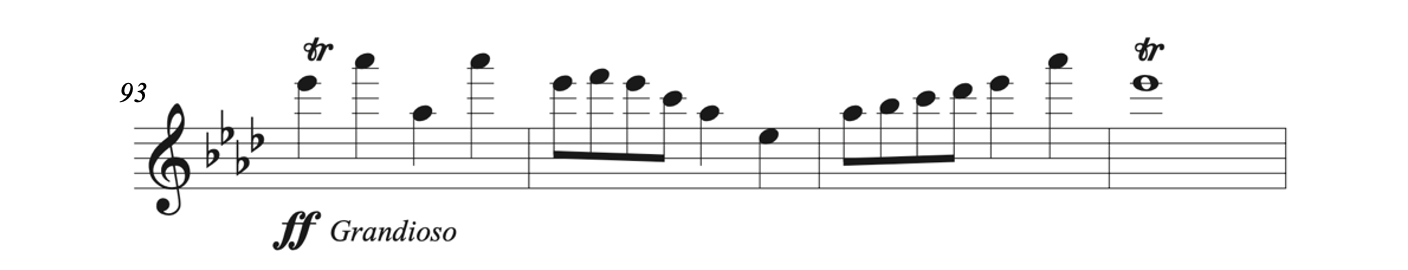

Beach’s Pastorale Wind Quintet includes two transposing instruments (Example 10.2.7).

Example 10.2.7. Transposing instruments: Beach[3], Pastorale Wind Quintet

We can immediately tell that the clarinet in B-flat and the horn in F are transposing instruments for two reasons:

- The names themselves (“in B-flat” and “in F”) tell us that these are not instruments in C. Therefore, they are transposing instruments.

- The key signatures are different from those instruments in C (i.e., the flute, oboe, and bassoon). Because the key signatures are different, we know these are transposing instruments.

Recall that the written pitches are the notes you read on the page, and the concert pitches are the notes you hear. In Example 10.2.7, the concert pitches are shown above the written pitches for the clarinet and horn.

- The concert pitches for the clarinet’s part sound a major second lower.

- The concert pitches for the horn’s part sound a perfect fifth lower.

Reading Transposing Instruments

- The name of the instrument tells you what the concert pitch is (e.g., a clarinet in B-flat means that when the clarinet plays C, you hear B-flat).

- Many transposing instruments will sound below their written pitch.

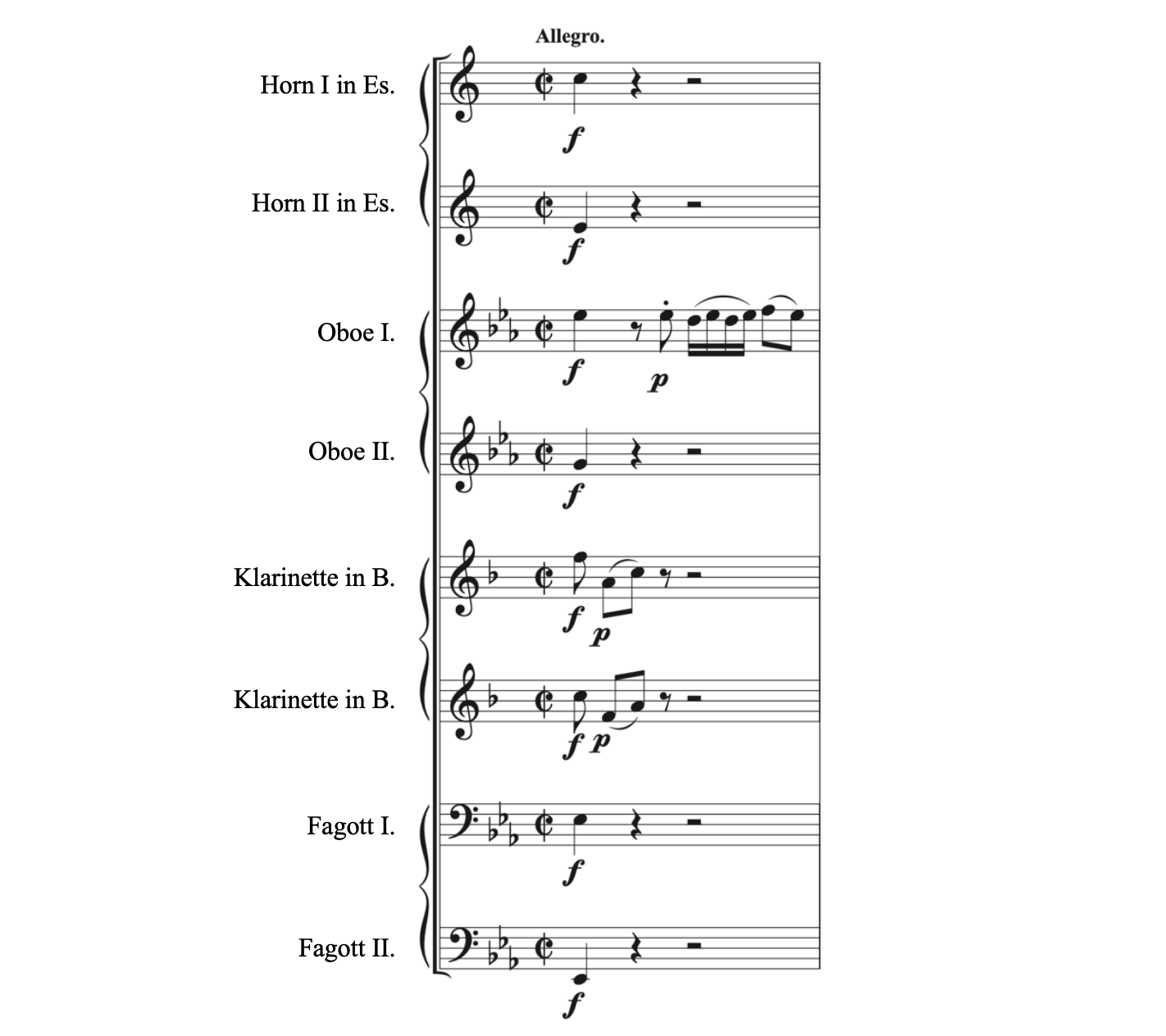

Many scores are written in other languages. In particular, they may be in German, French, or Italian. Observe the instruments listed in Beethoven’s Wind Octet (Example 10.2.8).

Example 10.2.8. Instruments in German: Beethoven[4], Wind Octet, Op. 103, i – Allegro

While most instruments, such as the Klarinette, are obvious cognates, Fagotto may appear unfamiliar. Fagotto refers to the bassoon.

There are several important things to remember when looking at a score in German.

- B refers to B-flat.

- This is often confusing to students, but if you remember that the clarinet is most commonly in B-flat (and not in B), this should help.

- Trompete in B in English is trumpet in B-flat.

- H refers to B.

- There are very few instruments in B, so it is unlikely that you will see an instrument in B.

- You may see “H” when it refers to the key of a piece. For example, Bach’s Mass in B Minor in German is Messe in H-Moll (Moll is the German word for minor).

- Es refers to E-flat.

- With the exception of B-flat, all other flatted notes in German add -s or -es.

- When the letter is a vowel, -s is added. For example, Schubert’s Mass in A-flat major in German is Messe in As-Dur (Dur is the German word for major).

- When the letter is a consonant, -es is added. For example, Schubert’s Impromptu in Ges-Dur is in G-flat Major.

- All sharped notes in German add -is. For example, Pejačević’s Sinfonie in Fis-Moll is her Symphony in F-sharp Minor.

- With the exception of B-flat, all other flatted notes in German add -s or -es.

This list above may seem overwhelming. The most important things to remember for transposing instruments in German is that German B refers to B-flat and Es refers to E-flat.

In the Romance languages (e.g., French, Italian, and Spanish), the names of transposing instruments use solfège. In particular, they use fixed do. Recall that with fixed do, solfège syllables are always affiliated with pitch names:

- C = do (can also use ut)

- D = re

- E = mi

- F = fa

- G = sol

- A = la

- B = si

There are a few differences from the solfège we learned in earlier chapters.

- Rather than using the solfège syllable do, composers will sometimes use ut.

- English: Trumpet in C

- French: Trompette en do (or ut)

- Italian: Tromba in ut (or do)

- Instead of ti, the syllable si is exclusively used.

- English: Horn in B

- French: Cor en si

- Italian: Corno in si

- For keys with flats, add the flat symbol after the solfège.

- English: Clarinet in B-flat

- French: Clarinette en si[flat symbol]

- Italian: Clarinetto in si[flat symbol]

One easy way to tell the difference between French and Italian is that “en” is French and “in” is Italian.

Compare how different the instruments are listed in a French score (Example 10.2.9) as opposed to a German score (Example 10.2.8).

Example 10.2.9. Instruments in French: Pfeiffer[5], Pastorale, Op. 71

Three of the instruments on the French score are cognates (Flûte, Clarinette, and Basson). The Cor is a horn and the Hautbois refers to the oboe. Based on the instruments’ names and the different key signatures, we see there are two transposing instruments.

- The Clarinette en La refers to the clarinet in A.

- The Cor en Mi refers to the horn in E.

For transposing instruments whose pitch name includes an accidental, such as the clarinet in B-flat, the accidental (not the word) is generally added to the solfège syllable (Example 10.2.10).

Example 10.2.10. Si-flat: Verdi[6], La forza del destino, Act III, Scene 8

In Example 10.2.10, the clarinet is the only transposing instrument. How do we know?

- The key signatures do not match with the other C instruments, such as the voice or violin.

- The name itself says “Clarinetto in Si-flat” (Clarinet in B-flat).

It may be easy to confuse French and Italian, since they both use solfège for the keys of transposing instruments. One easy way to tell the difference is that Italian uses “in” and French uses “en.” For example, French is “Clarinette en Si-flat” and Italian is “Clarinetto in Mi-flat”.

Example 10.2.11 shows the names of the most common transposing instruments in German, Italian, and French.

Example 10.2.11. Transposing instruments in different languages

Example 10.2.12 shows the keys of transposing instruments in other languages that you may come across when analyzing music.

Example 10.2.12. Keys of transposing instruments in other languages

There are many great books, websites, and resources that go into detail about all the different instruments, their names in various languages, and their transpositions.[7] The goal of this section is to be an introduction to figuring out basic transposing instruments.

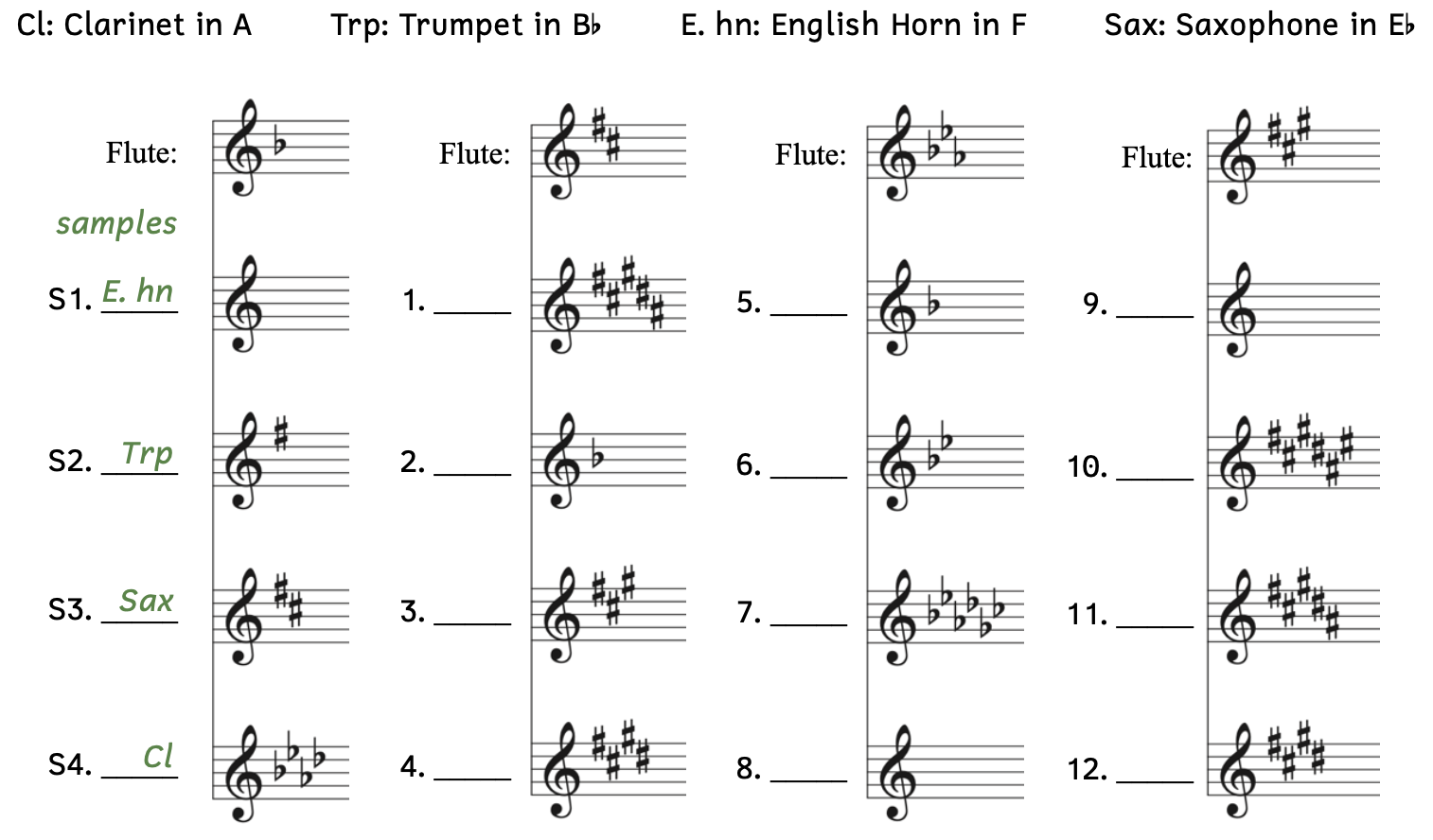

Practice 10.2A

Directions:

- Fill in the transposing instrument charts.

Sample. Clarinet in B-flat

1. Clarinet in A

2. Trumpet in B-flat

3. Saxophone in E-flat

4. Horn in F

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Practice 10.2B

Directions:

- In the second column, write the language of the instrument (German, French, or Italian).

- In the third column, write the name of the instrument and its key in English.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Practice 10.2C

Directions:

- Write the concert pitches above the written pitches on the score.

Chrétien[8], Quintette pour Flûte, Hautbois, Clarinette, Cor, et Basson

10.3 KEY SIGNATURES

Recall that the trumpet in B-flat is the most common type of trumpet. Because of this, the trumpet is sometimes listed as simply “trumpet.” Similarly, the clarinet in B-flat may also be labeled as only “clarinet.” When this is the case, you may need to rely on the key signature. As you learned, you can quickly identify transposing instruments on a score because their key signatures will not match with the other instruments. Compare the key signatures for the clarinet and the other C instruments in Example 10.3.1.

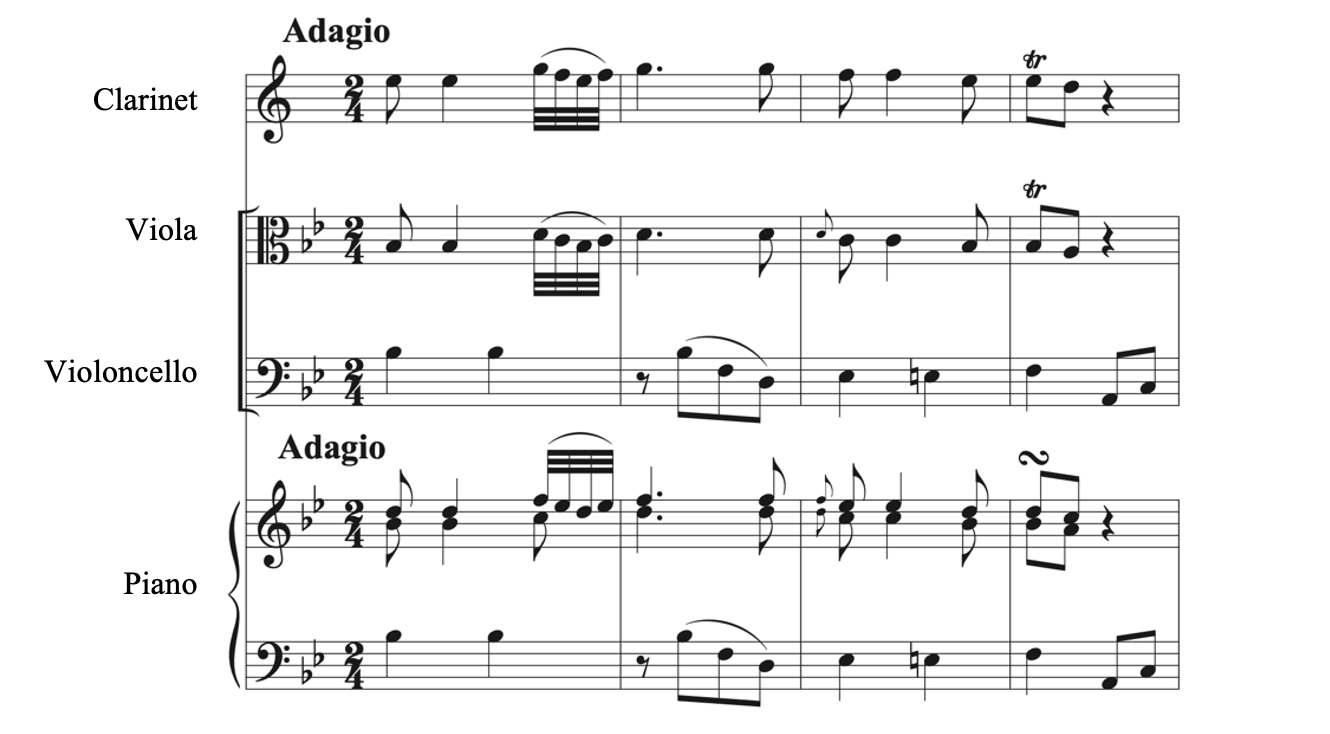

Example 10.3.1. Key signatures: Amalia[9], Divertimento, Adagio

The clarinet is a transposing instrument because its key signature is different. How do we know in what key the clarinet is? Is it a clarinet in B-flat or A, or even a different key? Take it step by step:

- The piano, viola, and cello are all instruments in C. Based on their parts, the key is B-flat major.

- The clarinet’s part has no sharps or flats, which belongs to C major.

- C is a major second above B-flat.

- Because the clarinet’s written part is a major second higher, this means that the clarinet’s concert pitch is a major second lower. Therefore, the clarinet in this example is a clarinet in B-flat because B-flat is a major second lower than C.

For the clarinet, when we found the concert pitch based on the written pitch, we transposed a major second lower. To find the key signature, we need to go in the opposite direction: a major second higher. This is because every note needs to be written a major second higher in order to sound a major second lower.

Let us practice finding the key of transposing instruments based on their key signatures. If the key is F major, how can we tell what keys instruments are in based only on their key signatures (Example 10.3.2)?

Example 10.3.2. Finding the key of transposing instruments

- Example 10.3.2A:

- The key signature is G major.

- Example 10.3.2B:

- The key signature is B-flat major.

- Because B-flat is a minor third above G, the transposing instrument is a minor third below C, which is A.

- Therefore, this is the key signature for an instrument in A.

- Example 10.3.2C:

- The key signature is D major.

- Because D is a perfect fifth above G, the transposing instrument is a perfect fifth below C, which is F.

- Therefore, this is the key signature for an instrument in F.

- Example 10.3.2D:

- The key signature is that of E major.

- Because E is a major sixth above G, the transposing instrument is a major sixth below C, which is E-flat.

- Therefore, this is the key signature for an instrument in E-flat.

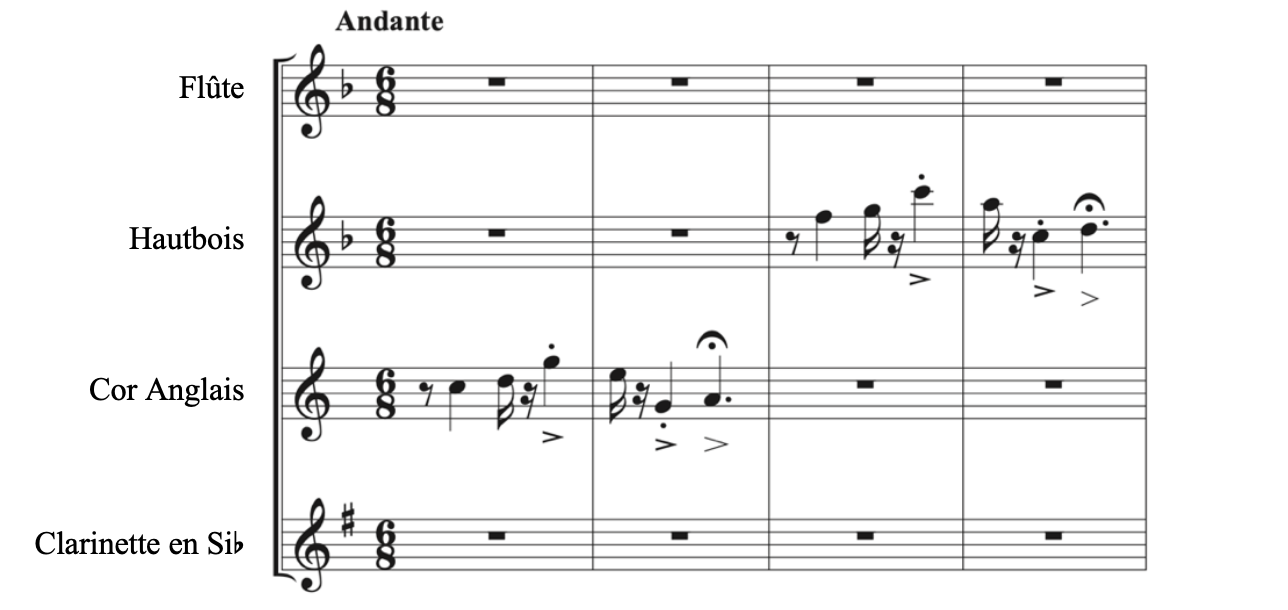

Most transposing instrument will include the transposition in their name (e.g., horn in E-flat). However, occasionally you will see a transposing instrument that does not give you the transposition in its name. You will know it is a transposing instrument because the key signature does not match, so you will need to figure out the transposition (unless you have the transposition memorized for that instrument). See the English horn’s (Cor Anglais) part in Example 10.3.3.

Example 10.3.3. English horn: Berlioz[10], Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14, iii – Scene aux champs – Andante (In the Country)

Assuming you do not know the transposition for the English horn, let’s use the key signature to figure it out.

- We know that the flute and oboe (hautbois) are instruments in C. Their key signature has one flat, which is F major.

- The English horn’s key signature has no sharps or flats, which is C major. The relationship between F and C is that C is a perfect fifth above F.

- Since notes in the English horn must be written a perfect fifth higher than C, this means that the English horn must be transposed a perfect fifth lower. Therefore, the English horn is in F, where notes sound a perfect fifth lower than written.

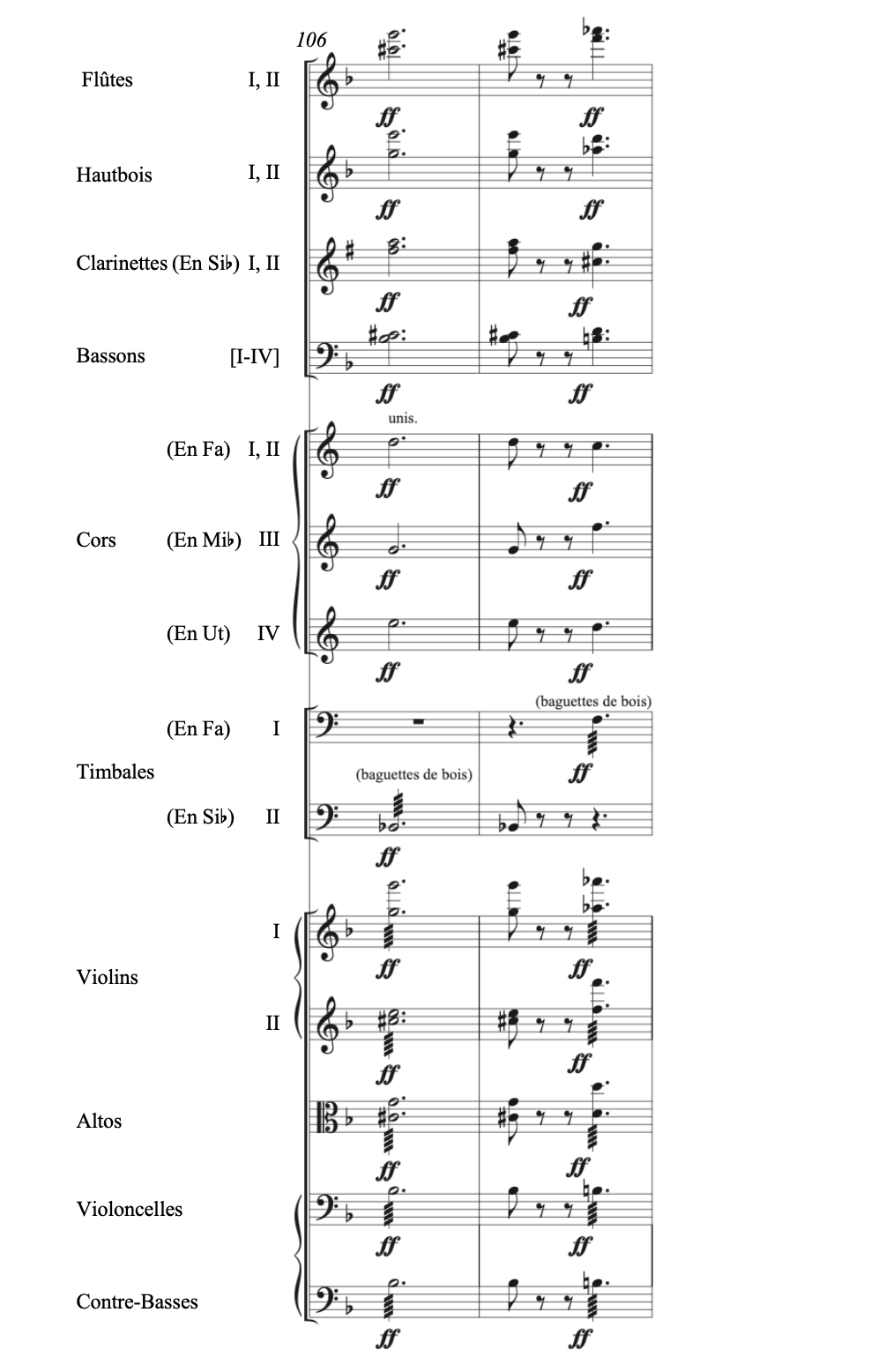

Sometimes the key signature is of no help. Historically, different horns used various crooks to produce sound. As a result, the horn’s part often omits any key signature. While Example 10.3.3 only showed the woodwinds, we now look at the entire score a little later in the same movement (Example 10.3.4).

Example 10.3.4. Complete score: Berlioz, Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14, iii – Scene aux champs – Andante (In the Country)

- The woodwinds (flutes, oboes, clarinets in B-flat, and bassoons) are bracketed together at the top of the score.

- All the instruments with the key signature of one flat (D minor) are instruments in C.

- The clarinets in B-flat sound a major second lower than written, so their key signature must be a major second above D minor (i.e., E minor).

- The horns are bracketed together.

- Notice that none of the parts for horns have key signatures.

- Horns I and II are in F (Fa); Horn III is in E-flat (Mi-flat); and Horn IV is in C (Ut).

- There are two timpani: one tuned to F (Fa) and one tuned to B-flat (Si-flat).

- The strings are bracketed at the bottom of the score.

- Although the strings include three different clefs, they are all instruments in C (as you can tell by the key signatures).

Even though the horns are transposing instruments, you cannot tell by the key signature. Instead, for the horns, rely on their names (e.g., horn in F).

In Example 10.3.4, it may appear that the cellos (Violoncelles) and double basses (Contre-Basses) are playing in unison. Although the double bass is an instrument in C, it is a transposing instrument in that its concert pitch is an octave lower than its written pitch. This is due to convenience, as writing their concert pitch would often require multiple ledger lines. There are several instruments in C whose concert pitch is either an octave lower or an octave higher (Example 10.3.5).

Example 10.3.5. Transposing instruments in C

- Example 10.3.5A: The double bass, also called the contrabass, sounds an octave lower than written.

- Example 10.3.5B: The guitar’s part is written in treble clef and sounds an octave lower than written.

- Example 10.3.5C: The celeste, or celesta, is also called a bell-piano and sounds an octave higher than written.

- Example 10.3.5D: The piccolo, a small-sized flute, sounds an octave higher than written.

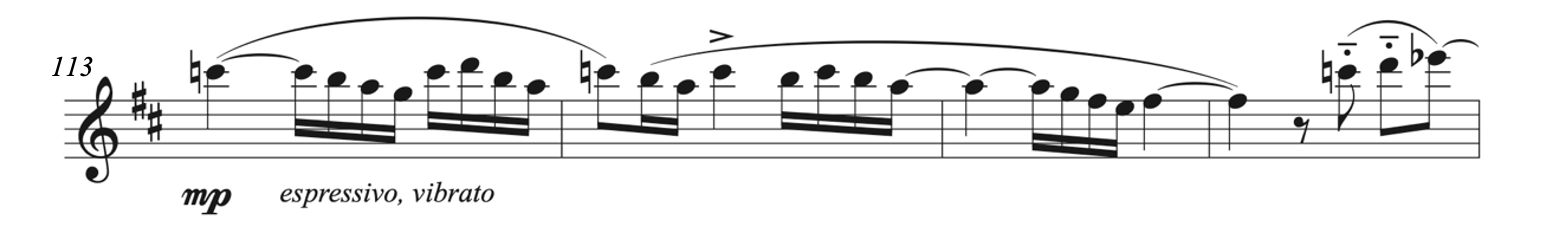

Instruments in C that transpose an octave higher or lower due often do so due to convenience. Take for instance, the piccolo’s solo in Example 10.3.6.

Example 10.3.6. Piccolo: Sousa[11], “The Stars and Stripes Forever”

The first written pitch is E-flat6 but its concert pitch is an octave higher: E-flat7. Imagine how many ledger lines it would require to write this part. Or how cluttered it would appear to constantly write 8va above everything. The fact that the piccolo always sounds an octave higher than its written pitch is indeed a convenience.

As you can see, many of the things we learned in earlier chapters are necessary in order to understand transposing instruments. You will find that as we learn more about music theory, these fundamentals will not go away. Be sure to continually brush up on the fundamentals including key signatures and intervals.

Transposing Instruments: Key Signatures

- Transposing instruments have a different key signature than instruments in C.

- You can use the key signature to figure out the transposition interval of the transposing instrument.

- The key signature will be in the opposite direction of how you figured out the concert pitch.

- One exception to using the key signature is the horn. The horn usually does not have any sharps or flats and you will need to rely on the instrument’s name to figure out the transposition interval.

Practice 10.3A

Directions:

- Based on the given key signatures for an instrument in C, fill in the blanks with the correct key for transposing instruments.

Practice 10.3B

Directions:

- Match the transposing instruments to their correct key signatures based on the key signature of the flute, which is an instrument in C. The instruments do not appear in the order of a typical score.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

10.4 WRITING FOR TRANSPOSING INSTRUMENTS

When finding the concert pitch for a transposing instrument, we determined the interval from C to the key of the transposing instrument and applied it to all the written pitches. For example, because the interval from C to B-flat is a major second lower, we transposed every written pitch down a major second to find the concert pitches for the trumpet in B-flat.

When writing for transposing instruments, we must apply the same interval, but in the opposite direction: In order to hear notes a major second lower, we must write the pitches a major second higher. For example, imagine that we want the violin and the trumpet in B-flat to play the following example in unison (Example 10.4.1).

Example 10.4.1. Violin example

- Because the trumpet in B-flat’s concert pitch is a major second lower than its written pitch, we must go in the opposite direction to find its written pitch based on its concert pitches.

- Transpose every note a major second higher to determine the written pitches for the trumpet in B-flat to play in unison with the violin (Example 10.4.2):

- The first note is a concert G4 and a major second higher than G is A. Therefore, the trumpet’s written pitch is A4.

- The second note is a concert B-flat4 and a major second higher than B-flat is C. Therefore, the trumpet’s written pitch is C5.

- The last note is a concert F-sharp4 and a major second higher than F-sharp is G-sharp. Therefore, the trumpet’s written pitch is G-sharp4.

Example. 10.4.2. Violin and trumpet in B-flat in unison

Always double check your work:

- “Trumpet in B-flat” means that when they play C, you hear B-flat. Therefore, the concert pitch is a major second lower than the written pitch.

- A major second below A is G.

- A major second below C is B-flat.

- A major second below G-sharp is F-sharp.

We will apply the same technique when writing the key signature for transposing instruments. Imagine that a piece of music is in D major. What would the key signature be for a clarinet in A? Follow these steps:

- The clarinet in A’s concert pitch sounds a minor third lower than its written pitch.

- Therefore, its written pitch must be a minor third higher.

- A minor third above D is F.

- The key signature for a clarinet in A would be that of F major in order to sound like D major (Example. 10.4.3).

Example 10.4.3. Key signature of a clarinet in A for the key of D major.

Now imagine that the key signature of a flute (an instrument in C) is E minor. What would the key signature for a tenor saxophone in B-flat be? Use the same steps as if the key were in major.

- B-flat is a major second lower than C.

- Therefore, its written pitch must be a major second higher.

- A major second above E is F-sharp.

- The key signature for a tenor saxophone in B-flat would be that of F-sharp minor in order to sound like E minor (Example. 10.4.4).

Ex. 10.4.4. Key signature of a tenor saxophone in B-flat for the key of E minor

Although identifying the key signature for the tenor saxophone in B-flat uses the same steps as the clarinet in B-flat and the trumpet in B-flat, there is an important difference when writing for the tenor saxophone. The tenor saxophone in B-flat actually sounds a major ninth, or compound major second, lower (P8 + M2) than its written pitch.

In Example 10.3.5, we saw that although the double bass and guitar are instruments in C, they sound an octave lower. Similarly, some instruments (especially with words like “bass” or “baritone”) also sound an octave lower (Example 10.4.5).

Example 10.4.5. Transposing instruments that sound more than an octave lower

- Example 10.4.5A: The tenor saxophone is in B-flat, but does not sound a major second lower than its written pitch. Instead, it sounds a major ninth (compound major second) lower.

- Example 10.4.5B: The baritone saxophone is in E-flat, but does not sound a major sixth lower than its written pitch. Instead, it sounds a compound major sixth (one octave plus major sixth) lower.

- Example 10.4.5C: Like the tenor saxophone, the bass clarinet in B-flat sounds a major ninth (one octave plus a major second) lower when written in the treble clef.

- In the bass clef, the bass clarinet in B-flat sounds only a major second lower than written.

Imagine that we want the cello and the baritone saxophone to play the following example in unison (Example 10.4.6).

Example 10.4.6. Cello example

First, let us figure out the key signature for the baritone saxophone in E-flat.

- E-flat (key of the baritone saxophone) is a major sixth lower than C.

- Therefore, its written pitch must be a major sixth higher.

- A major sixth above F (key of Example 10.4.6) is D.

- The key signature for a baritone saxophone in E-flat would be that of D major in order to sound like F major.

Next, follow the steps to determine the written pitches for the baritone saxophone.

- Because the baritone saxophone in E-flat’s concert pitch is a compound major sixth lower than its written pitch, we must go in the opposite direction to find its written pitch based on its concert pitches.

- Transpose every note a compound major sixth higher to determine the written pitches for the baritone saxophone in E-flat to play in unison with the cello (Example 10.4.7):

- The first note is a concert F3 and a major sixth higher than F3 is D4. However, to make it a compound major sixth, we must add an octave to it, making it D5. Therefore, the baritone saxophone’s written pitch is D5.

- The second note is a concert C-sharp3 and a compound major sixth higher than C-sharp3 is A-sharp4.

- The third note is a concert D3 and a compound major sixth higher than D3 is B4.

- The late note is a concert E-flat3 and a compound major sixth higher than E-flat3 is C5.

Example 10.4.7. Cello and baritone saxophone in E-flat in unison

Always double check your work:

- “Baritone saxophone in E-flat” means that when they play C, you hear E-flat. Because it is a baritone instrument, the concert pitch is a compound major sixth lower than the written pitch.

- A compound major sixth below D5 is F3.

- A compound major sixth below A-sharp4 is C-sharp3.

- A compound major sixth below B4 is D3.

- A compound major sixth below C5 is E-flat3.

Notice that although the cello and baritone saxophone are playing in unison, the baritone saxophone’s part is written in the treble clef. This is because its concert pitch is a compound major sixth lower.

- Writing the baritone saxophone’s part in bass clef would require excessive ledger lines.

- You may wonder why the baritone saxophone’s part is not written in bass clef, where it only transposes down a major sixth (as opposed to in treble clef, where it transposes down a compound major sixth). This would require that saxophonists would need to be fluent in reading in another clef.

Some instrumentalists are expected to be read fluently in more than one clef. We saw this in Example 10.4.5, where the bass clarinet is written using two different clefs.

- In the treble clef, the concert pitch sounds a major ninth lower.

- In the bass clef, the concert pitch sounds a major second lower.

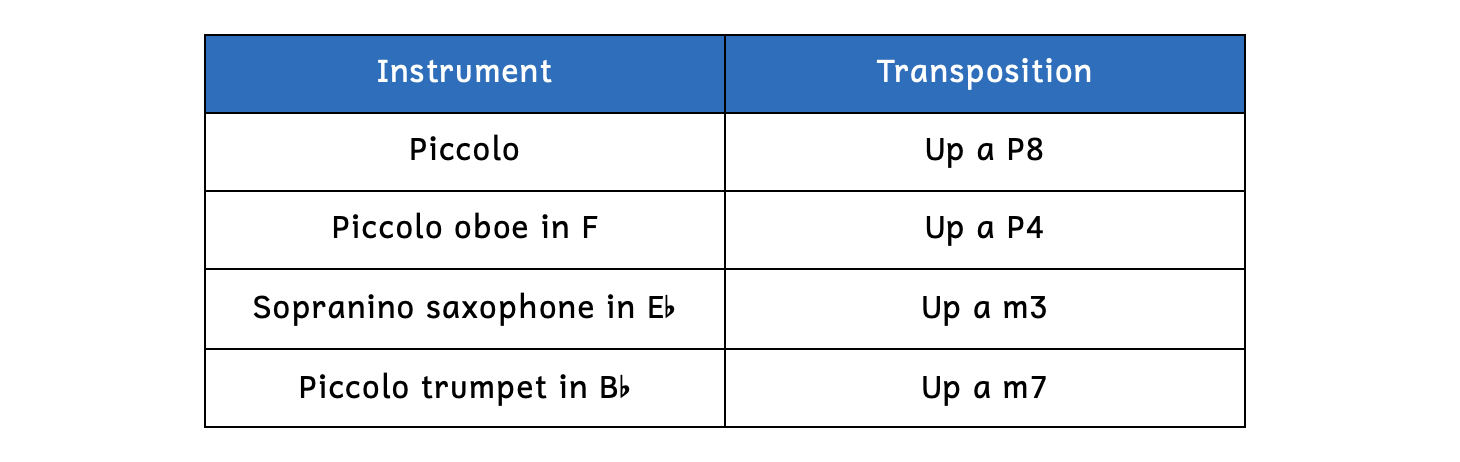

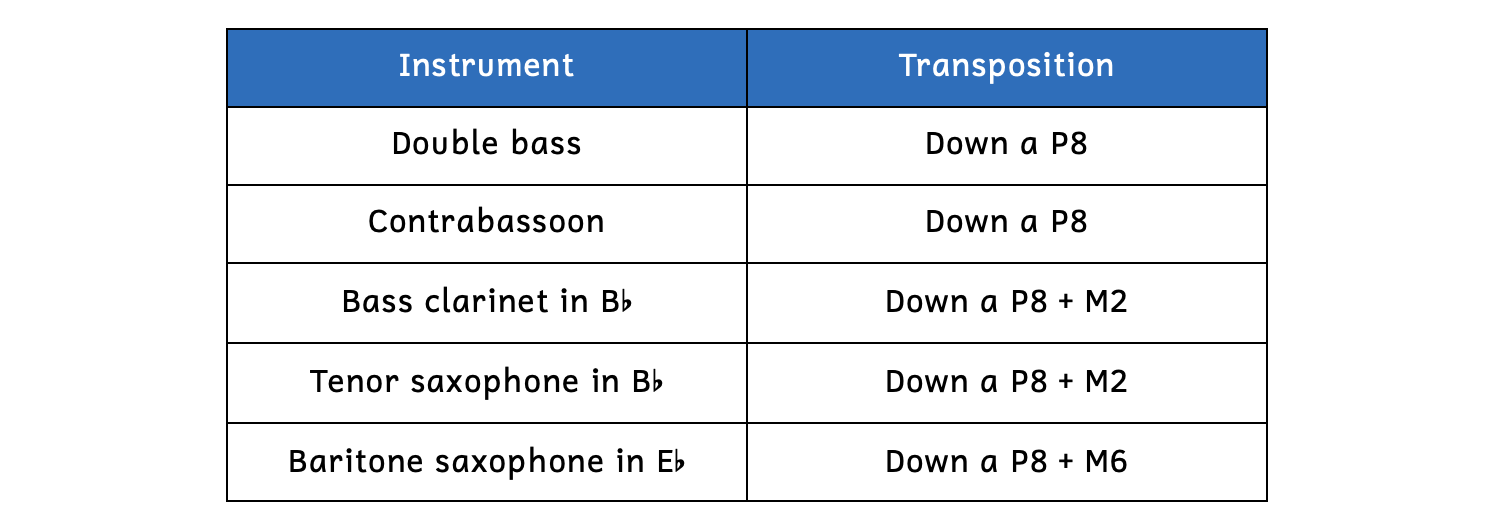

In addition to the instruments already mentioned in this chapter, there are additional less common instruments. For example, there are at least ten different types of trumpets. You are not required to know all the different types of trumpets, but should be familiar with the most common band instruments and the interval of their transpositions (Example 10.4.8).

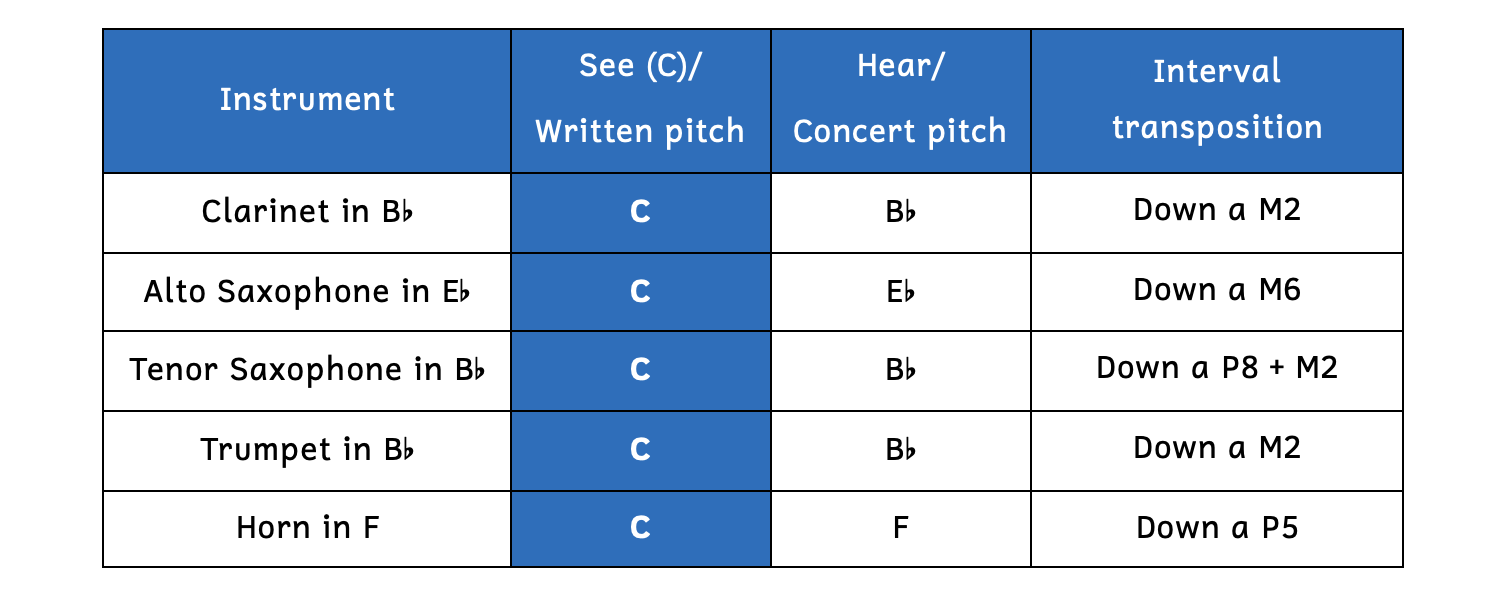

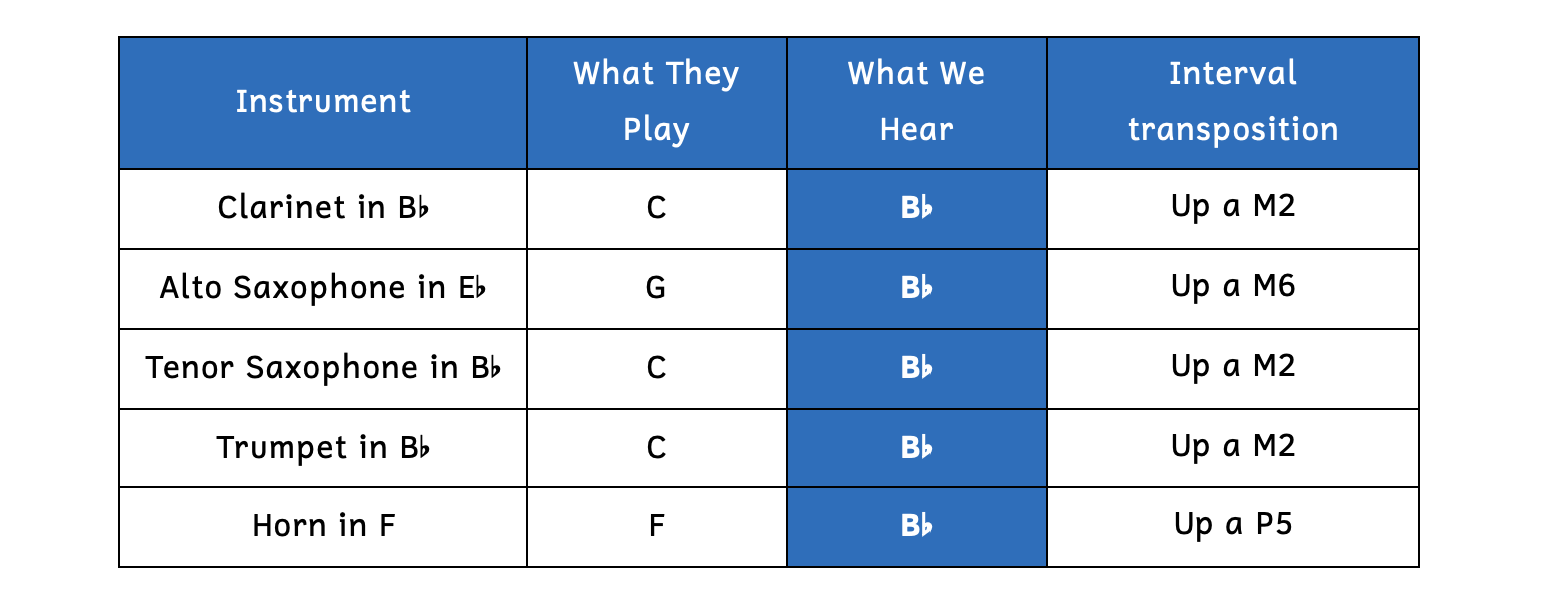

Example 10.4.8. Common band transposing instruments

If you ever played in a band, you may recall hearing the conductor asking for everyone to tune to concert B-flat. For the C instruments, such as the flutes, they will simply play B-flat. However, for all transposing instruments, they will need to play a different pitch. Example 10.4.9 shows the same instruments from Example 10.4.8, and what they would need to play to tune to B-flat.

Example 10.4.9. Tuning to concert B-flat

The chart in Example 10.4.9 shows us that for an alto saxophone to tune to B-flat, it must play a G (since their concert pitch sounds a major six lower). For the tenor saxophone, although their concert pitch sounds a major ninth lower, when tuning to a generic B-flat, it simply needs to play a C, which is a major second higher than B-flat.

Writing for Transposing Instruments

- Decide the relationship between the transposing instrument you are writing for and the concert pitch.

- When writing for this transposing instrument, you must write pitches at the same interval, but in the opposite direction (e.g., if the concert pitch is a major second lower than the written pitch, you must write a major second higher than the concert pitch).

- Once you establish the tonic, you can write in the key signature. Remember that some instruments like the horn often do not use a key signature.

Range and Register

What if you are asked to write “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” in A-flat major for a clarinet in B-flat and gave them Example 10.4.10?

Example 10.4.10. “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” for flute?

You would most likely have an angry flutist. First, the flutist may not be as comfortable with the bass clef. More importantly, Example 10.4.6 is out of range for the flute. A range is how low to how high a person can play an instrument or can sing.

Let’s look at the general range of a flute, which is approximately from C4 to C7 (Example 10.4.11).

Example 10.4.11. Range of a flute

Ranges vary depending on the musician (and textbook). A beginning student will have a smaller range, while advanced clarinets can reach beyond the notes shown above. When writing for any instrument or voice, it is always safest to avoid the extremes. For vocalists, the most common part of a range in a song is called the tessitura. It does not include the extremes.

A range is divided into registers. A register is a portion of the range based on high, middle, or low. Example 10.4.12 shows the different registers for a flute.

Example 10.4.8. Registers of a flute

- Example 10.4.12A: The low register of a flute is C4 to D-sharp5.

- Example 10.4.12B: The middle register of a flute is E5 to C-sharp6.

- Example 10.4.12C: The higher register of a flute is D6 to C7.

Range and register are not the same. While Example 10.4.11 illustrated the range of the flute, Example 10.4.12 showed the various registers. There are many websites that list the ranges of all the instruments.[12]

Range Versus Register

- The range of an instrument or voice refers to how high or low they can sound.

- The register of an instrument or voice refers to where in the range the music lies: low register, middle register, or high register.

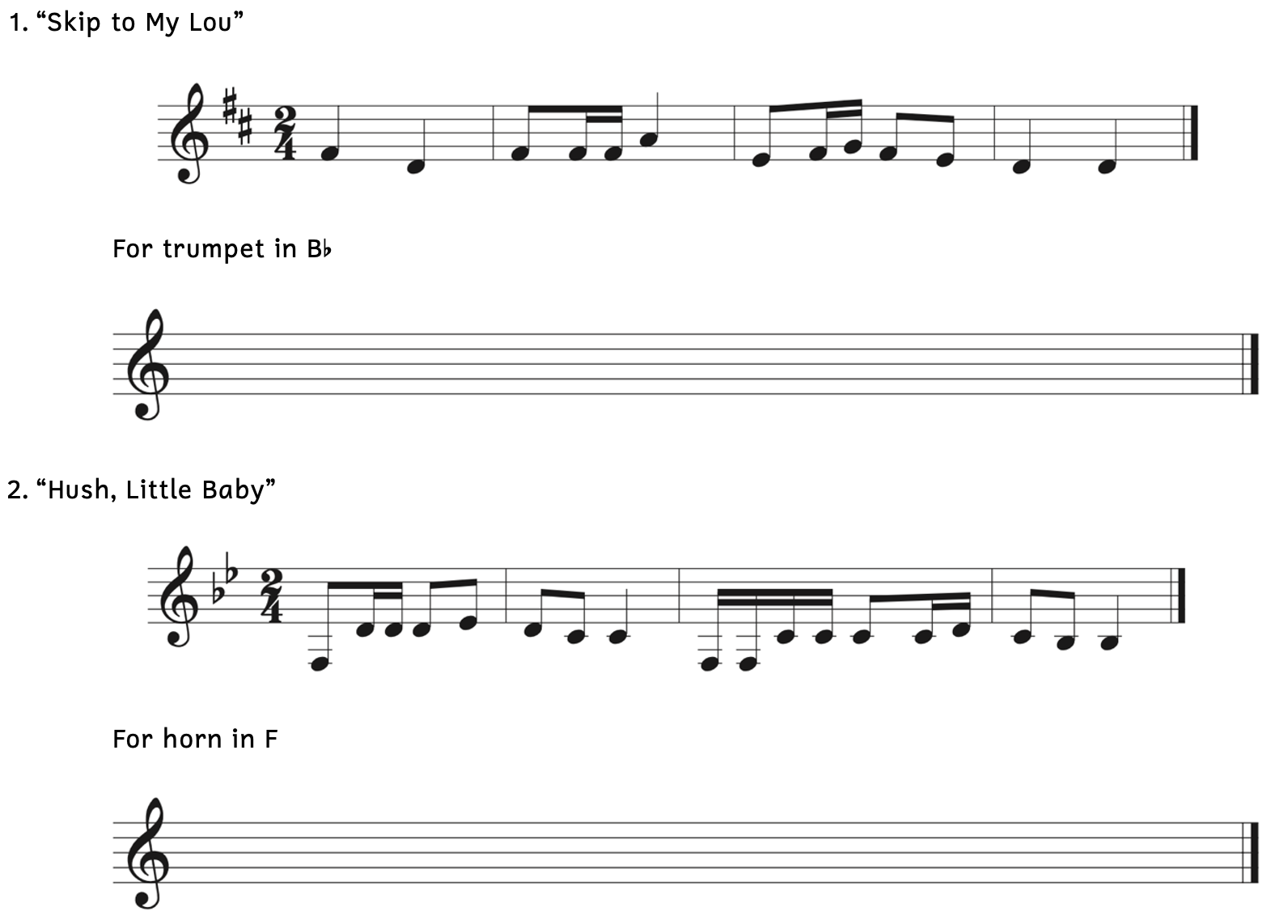

Practice 10.4A

Directions:

- Write the following melodies for the different transposing instruments, adding a key signature when necessary.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 10.4B

Directions:

- The key signature, pitches, and rhythm have been given for the violin.

- Write the key signatures for all the other instruments. The instruments are written in Italian.

- Using the same rhythm as the violin’s, write in the pitches as asked.

Farrenc, Nonet, Op. 38

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 10.4C

Directions:

- Based on the given key signatures for an oboe, which is an instrument in C, write the key signatures for the given transposing instruments.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

10.5 TEXTURE

In Example 10.3.5, Berlioz’s movement from Symphonie Fantastique began with an English horn followed by an oboe. Later, other instruments enter as more than one instrument perform at a time. In addition to instrumentation, composers can also create variety with musical texture (or simply texture). Texture refers to how many melodies are performed, and what else is happening at the same time. There are four different types of musical texture:

- Monophony

- Homophony

- Polyphony

- Heterophony

Monophony

The single use of the English horn followed by the oboe in Example 10.3.5 are examples of monophony. Monophony is when one (or all) instruments or voices perform the same melody at the unison or octaves. The clearest example of monophonic texture is when there is only one voice or line, such as in Example 10.5.1.

Example 10.5.1. Monophony: Opening melody from Mozart[13], Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor, K. 478, i – Allegro

Whether there is one violinist or one hundred violinists performing at the same time, it would still be considered monophony because there is one melody with the same pitches and the same rhythm.

Moreover, if a group of instruments or vocalists perform the melody in several octaves, it would still be considered monophony. Monophonic music can be quite dramatic, as seen in Example 10.5.2.

Example 10.5.2. Monophony: Opening from Mozart, Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor, K. 478, i – Allegro

In Example 10.5.2, four different instruments are playing in unisons or octaves covering three octaves. It is still considered monophonic because they all have the same melody in the same rhythm using the same notes (even though they are in different octaves).

At the start of this movement, three string instruments and the piano play forte, allegro, and in unison or octaves. The dynamic opening is quite energetic, as you can imagine four people, varying from children to adults, yelling at you in unison: “Duck! Cover your head!” This would make your heart race more than one person saying that to you.

If non-pitched percussion instruments (such as a drum set) were to join the ensemble, it would still be considered monophony, such as in Example 10.5.3.

Example 10.5.3. Monophony: “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” for clarinet, horn, and bass drum

In Example 10.5.3, the addition of the bass drum does not change the music from being monophonic because the percussion instrument is unpitched. However, if the percussion instrument was pitched (such as the marimba or steelpan) and if it played different pitches or a different rhythm, then the music would no longer be monophonic.

Although both the clarinet and horn are playing in unison in Example 10.5.4, it is likely that you are able to tell that there are two different instruments. There is probably a good chance you can even hear that the instruments are a clarinet and a horn. How is this possible, if the concert pitch for both instruments is B-flat4? This is due to timbre (pronounced “tam-bur”), which refers to the uniqueness of sounds. Timbre is also the reason why you can recognize whether it is your mom or your sister on the phone. Just as two people of the same height and build can have voices that are distinguishable, two instruments (such as two violins) can be distinguishable (although not as easily as two different instruments). Explaining timbre can be scientific and difficult to grasp in the scope of this theory textbook, so it is recommended that you watch a video to show how it works in action.[14]

Homophony

While monophony refers to a single melody (whether by one or many performers), homophony refers to a melody with accompaniment. Homophony is a type of musical texture in which there is one melody while other voices or instruments perform a subordinate role.

Example 10.5.4 is an example of homophony, as the violin in Rogers’s Violin Sonata begins with the melody while the piano plays an accompanimental role.

Example 10.5.4. Homophony: Rogers[15], Violin Sonata, Op. 25, i – Allegro

Listen to only the piano’s part in Example 10.5.4. Do you hear how it lacks a true melody? Indeed, its job is to support the more interesting melody in the violin. Since there is a melody (violin) and accompaniment (piano), this excerpt is homophonic.

Homophonic texture does not require two or more instruments or voices. In Example 10.5.5, homophony is achieved on the piano.

Example 10.5.5. Homophony: Price[16], “Ticklin’ Toes”

Although the left hand of the piano plays a more interesting part in Example 10.5.5 with its descending bass line than the piano’s part in Example 10.5.4, it is still secondary to the right hand’s melody. Therefore, Example 10.5.5 is homophonic.

Homophony can also occur when a melody is harmonized by other voices or instruments in the same rhythm. In other words, the other voices or instruments do not have the main melody but have different notes to support the melody, such as in Example 10.5.6.

Example 10.5.6. Homophony: Reichardt[17], “Weihnachten: Welche Morgenröten wallen” (“Christmas: What Dawns Wave”)

In Example 10.5.6, the four voices are singing different notes. However, Soprano #1 clearly has the melody. (For example, sing the melody in Alto #2 to compare.) Since there is one melody and the other voices serve as support, Example 10.5.6 is homophonic.

Music can alternate between monophony and homophony, as seen later in Mozart’s Piano Quartet (Example 10.5.7).

Example 10.5.7. Monophony and homophony: Mozart, Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor, K. 478, i – Allegro

Monophony and homophony alternate in the opening of Example 10.5.7. While one may think that when the piano performs alone, the texture is monophonic, it is quite the opposite in this example. The first two bars of both systems are monophonic (as explained in Example 10.5.2). When the piano plays by itself at the end of both systems, the right hand has the melody while the left hand has an accompanying role, creating a homophonic texture.

Polyphony

Sometimes more than one instrument or voice has the melody—imagine telling a story and someone else begins telling the same story (or a different story) while you are midway through your story. When more than one voice or instrument has the same melody overlapping one another, or different melodies occurpolyphonic at the same time, the texture is polyphonic, as in Casulana’s madrigal in Example 10.5.8. A madrigal is a secular polyphonic song for multiple voices without instruments. The text often plays a strong role, and its peak was during the Renaissance.

Example 10.5.8. Polyphony: Casulana[18], “Stavasi il mio bel sol” (“My Beautiful Sun Stood”)

- In Example 10.5.8, the melody first appears in Alto #2 but is soon joined by an independent melody in Alto #1.

- As soon as Alto #1 interrupts Alto #2, there is polyphony because there are two individual melodies.

- In measure 4, the Soprano enters with the same melody as Alto #2, but an octave higher.

The number of voices with simultaneous different melodies does not matter for polyphony: as long as there is more than one voice, it is polyphonic.

Polyphonic music does not need to literally include multiple voices; it can be multiple instruments or even a single instrument, as in the opening of Bach’s Fugue No. 6 (Example 10.5.9).

Example 10.5.9. Bach[19], Fugue No. 6 from Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, BWV 851

- The melody begins in the right hand of the piano. Recall that in a fugue, the opening melody is called the subject (see Chapter 9, Section 9).

- While the right hand is completing the end of the subject, the left enters with the same melody, transposed at the dominant (i.e., in the key of A minor instead of D minor). In a fugue, the second melody at the dominant is called the answer.

- Once the answer appears in the left hand, the melody in the right hand is no longer called the subject, but instead, the countersubject.

It is important to remember that Example 10.5.9 is polyphonic only because the melody in the first voice is still continuing when the melody in the second voice begins. Imagine if you are listening to someone tell a story about their first day of class and in the middle of their story, the person next to them starts telling their story about their first day of class. As you can imagine, it can be hard to concentrate on two people telling their stories at the same time. Similarly, polyphonic music can sound complex and confusing when done incorrectly.

Heterophony

The last type of texture is heterophony, which is when the same melody occurs simultaneously in different voices, but with alterations or embellishments. It is seldom used in Western music.

Example 10.5.10. Heterophony: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”

In Example 10.5.10, the top part has the basic melody. At the same time, the bottom part sings the melody with alterations or embellishments. When this occurs, the music has a heterophonic texture.

Musical Texture

- Monophony: One melody

- Can be a single instrument/voice or several/many instruments/voices in different octaves (as long as the notes and rhythm are the same)

- Can include non-pitched percussion

- Homophony: Melody and accomopaniment

- Polyphony: More than one melody at the same time (but not the same notes at the same time)

- Heterophony: A melody simultaneously occurring with an embellished version of the same melody.

Practice 10.5A

Directions:

- Identify the following excerpts from Zimmermann’s Suite Trio for Violin, Cello, and Piano as monophonic, homophonic, polyphonic, or heterophonic.

sample. IV – Air: Allegretto sostenuto e cantabile. Texture: Homophonic

1. I – Introduction et Allegro: Andante maestoso. Texture: __________

2. II – Canon à la 7ième: Allegretto grazioso. Texture: __________

3. III – Gavotte: Allegro ma non troppo. Texture: __________

4. V – Gigue. Allegro con spirito. Texture: __________

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Practice 10.5B

Directions:

- Add a second voice to “Frère Jacques” to create the given textures.

sample. Heterophony

1. Monophony

2. Homophony

3. Polyphony

Click here to watch the tutorial.

10.6 ANALYSIS: RAVEL, BOLÉRO

Ravel’s Boléro is a popular work for a large orchestra. Ravel was known for his orchestration skills. With a continuous percussive ostinato, Ravel cleverly moves the famous melody from instrument to instrument, taking advantage of the unique timbres of each. An ostinato is a when a rhythm or pitches are continually repeated. We can trace the two main melodies through the work, as the piece begins with simple monophony and gradually grows.

The first occurrence of the melody appears in the flute, which is an instrument in C (Example 10.6.1).

Example 10.6.1. Flute (Flûte) melody in Ravel[20], Boléro

The next appearance is in the clarinet in B-flat (Example 10.6.2).

Example 10.6.2. Clarinet in B-flat (Clarinette en Si-flat) in Ravel, Boléro

Because the clarinet in B-flat sounds a major second below its written pitch, Example 10.6.2 is written a major second higher than Example 10.6.1. Another appearance of the melody occurs in the oboe d’amore, which is an instrument in A (Example 10.6.3).

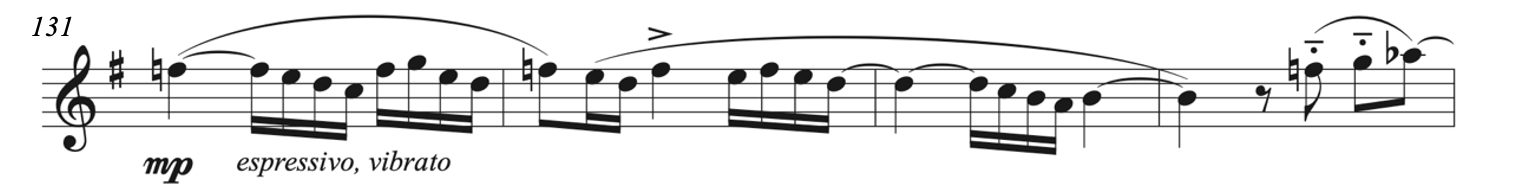

Example 10.67.3. Oboe d’amore (hautbois d’amour) in Ravel, Boléro

As an instrument in A, the oboe d’amore sounds a minor third below its written pitch. Example 10.6.3 is written a minor third higher than Example 10.6.1.

There is a second closely-related main melody in Boléro, which first appears in the bassoon (Example 10.6.4).

Example 10.6.4. Bassoon (basson) in Ravel, Boléro

Sharing the same key signature as the flute, the bassoon is another instrument in C. Notice that the bassoon’s part is in the tenor clef (which is not uncommon for the bassoon). However, the upper register of this example is quite high for the bassoon—the melody begins on B-flat4. This melody appears later in the clarinet in E-flat (Example 10.6.5).

Example 10.6.5. Clarinet in E-flat (Petite Clarinette en Mi-flat) in Ravel, Boléro

Because this is a petite clarinet (considered a sopranino member of the clarinet family), this clarinet actually sounds a minor third higher than its written pitch. Recall that the bassoon’s melody in Example 10.6.4 began high in its register on B-flat4. Similarly, Example 10.6.5 begins not at the unison with the bassoon, but an octave higher with G5.

The key signature for the clarinet in E-flat has three sharps because A major is a minor third below C (and the clarinet in E-flat sounds a minor third above C).

As previously mentioned, most, but not all, transposing instruments sound lower than the written pitch. Usually instruments that are the smallest member of an instrument family transpose higher. We learned earlier that the piccolo sounded an octave higher than written. These instruments are often labeled with words such as “soprano” or “piccolo.” Some examples are listed below (Example 10.6.6).

Example 10.6.6. Examples of transposing instruments that sound higher than written

On the other hand, instruments that are the largest member of an instrument family will sometimes transpose down by a compound interval (i.e., one octave plus the specified interval). We learned earlier that the double bass sounded an octave lower than written. These instruments are often labeled with words such as “contra” or “bass.” Some examples are listed below (Example 10.6.7).

Example 10.6.7. Examples of transposing instruments that sound an octave or more lower than written

As seen in Example 10.6.7, the tenor saxophone sounds more than an octave below its written pitch. Observe the tenor saxophone’s melody in Boléro (Example 10.6.8).

Example 10.6.8. Tenor saxophone in B-flat (Saxophone Tenor en Si-flat) in Ravel, Boléro

Although the first written pitch is C6, the concert pitch is a major ninth lower (a P8 + M2). Therefore, the note we hear is B-flat4.

Later, the second melody appears in a high-ranging saxophone. In the score, Ravel wrote the part for the sopranino saxophone in F, whose concert pitch would be a perfect fourth above its written pitch (Example 10.6.9).

Example 10.6.9. Sopranino saxophone in F (Saxophone Sopranino en Fa) in Ravel, Boléro

Although Ravel wrote the part for sopranino saxophone in F, there is actually no such instrument and scholars believe that Ravel made an error in the score. When the piece is performed today, it is usually played by a soprano saxophone in B-flat (Example 10.6.10).

Example 10.6.10. Soprano saxophone in B-flat in Ravel, Boléro

The soprano saxophone in B-flat sounds a major ninth higher (a P8 + M2). Because of the new key signature and pitches, Example 10.6.10 sounds exactly the same as Example 10.6.9.

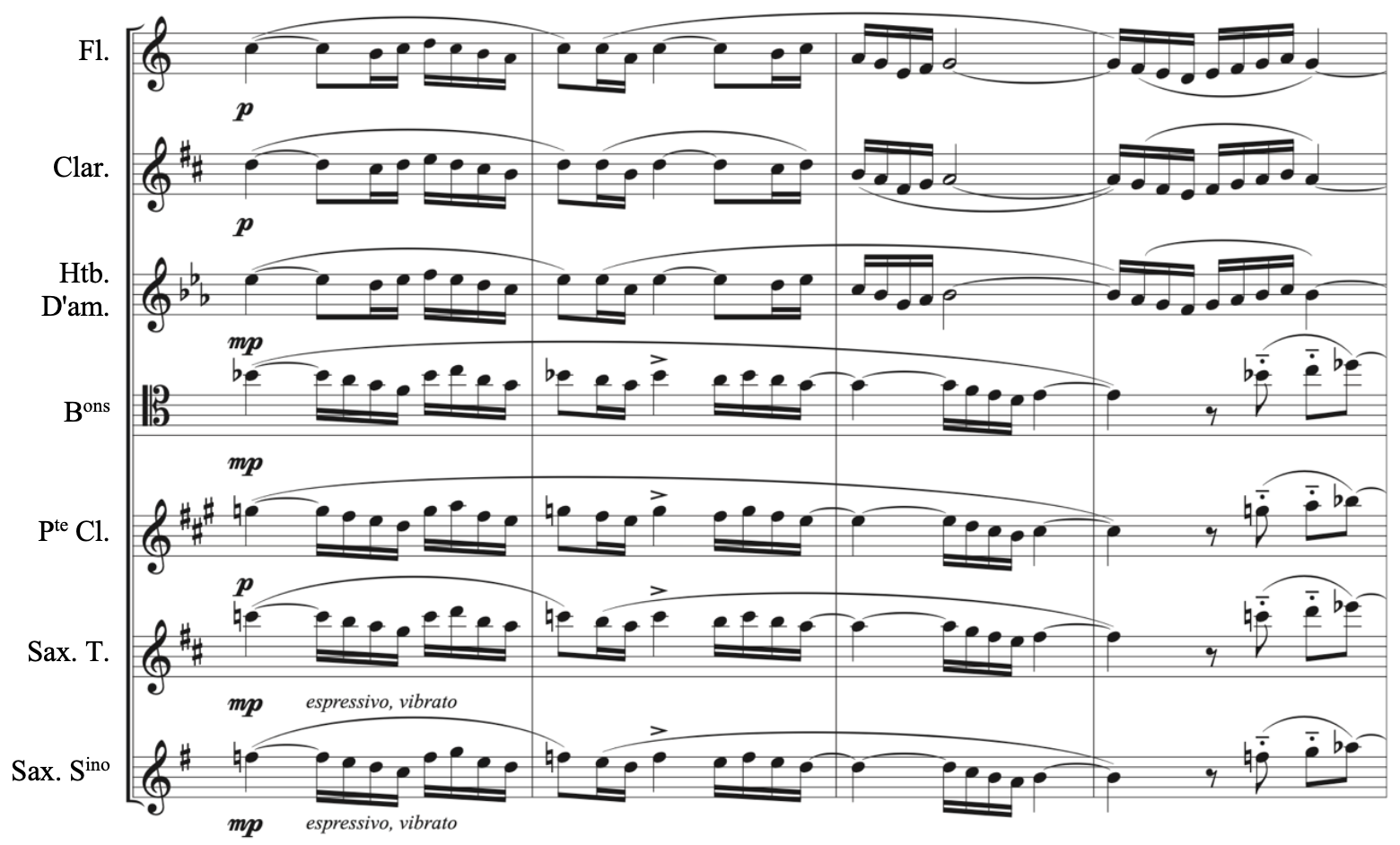

When we place all these instrumental openings side by side, we can see the wide range of transposing instruments (Example 10.5.11).

Example 10.5.11. Various instruments side by side in Boléro

- The flute, clarinet, and oboe d’amour have the same first melody and their concert pitches are in unison.

- The bassoon, petite clarinet, tenor saxophone, and sopranino saxophone have the same second melody.

- The bassoon, a C instrument, begins with B-flat4.

- The petite clarinet, being a “petite” instrument, sounds a third higher so begins with B-flat5.

- The tenor saxophone, being a “tenor” instrument, sounds a major ninth lower so begins with B-flat4.

- The sopranino saxophone in F, being a “sopranino” instrument, sounds a perfect fourth higher so begins with B-flat5.

Compare how, despite sounding the same (or an octave apart), each instrument’s part includes a different key signature. Looking at these instruments’ parts side by side gives us a better understanding of how transposing instruments work.

Listen to the entire movement without the score, and appreciate the various timbres and musical textures.

SUMMARY

-

-

- Instruments in C (or C instruments) are instruments whose written pitch (the note we see) is the same as their concert pitch (the note we hear). [10.1]

- Transposing instruments are instruments whose written pitch is not the same as their concert pitch. There are several ways to tell when an instrument is a transposing instrument. [10.1]

- The instrument’s name includes the key of the instrument (e.g., trumpet in B-flat).

- The key signature does not match with the other instruments in C.

- Transposing instruments help performers in that they allow musicians to learn one set of fingerings for a group of instruments and make reading music easier with fewer ledger lines. [10.1]

- To find the interval between a transposing instrument’s written pitch and concert pitch, it is helpful to construct a transposing instrument chart where the first column shows what you see/C and the second column shows what you hear. Remember that the first column always begins with C, the homophone of “see”. [10.2]

- In German, B means B-flat, H means B, and Es means E-flat. The Romance languages use solfège (e.g., cor en mi is horn in E and clarinette en si-flat is clarinet in B-flat). [10.2]

- Some instruments in C sound an octave higher or lower than their written pitch. [10.3]

- Comparing key signatures of transposing instruments to the key signature of instruments in C will tell you the key the instrument is in. Some instruments, such as the English horn, do not tell you the transposition. [10.3]

- The key signature is not reliable for the horn, who normally does not include any key signature. [10.3]

- When writing for transposing instruments, go in the opposite direction as when you found the concert pitch. [10.3]

- When writing music, always keep in mind the range (how high and low the instrument or voice can sound) and in what register (low, middle, or high) you want the music. [10.4]

- Musical variety can be created by using different timbres, which refers to the unique sound of each instrument or voice. [10.5]

- Musical variety can also be accomplished by different textures. [10.5]

- Monophony: one melody

- Homophony: one melody and accompaniment

- Polyphony: more than one melody

- Heterophony: simultaneous melodies, but with embellishments

- Ravel’s Boléro is well known for the different timbres by various instruments performing the same melody. [10.6]

-

TERMS

-

-

- concert pitch

- countersubject

- heterophony

- homophony

- instruments in C (or C instruments)

- madrigal

- monophony

- ostinato

- polyphony

- range

- register

- tessitura

- texture (or musical texture)

- timbre

- transposing instrument

- written pitch

-

- Special thanks to Dr. Brian Shelton and Dr. Caitlin Beare, for their help with transposing instruments. ↵

- Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was a French composer and pianist. ↵

- Amy Beach (1867-1944) was an American composer and pianist. ↵

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was a German composer. ↵

- Georges Jean Pfeiffer (1835-1908) was a French composer and pianist. ↵

- Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) was an Italian composer ↵

- Excellent resources include Charles Leinberger’s web page https://utminers.utep.edu/charlesl/transpose.html and Yale University’s web page https://web.library.yale.edu/cataloging/music/names-keys-french-german-italian-and-spanish. ↵

- Hedwige Chrétien (1859-1944) was a French composer. ↵

- Duchess Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1739-1807) was a German composer. ↵

- Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) was a French composer and author of Treatise on Instrumentation (1844). ↵

- John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) was an American composer known as "The March King." ↵

- Some websites include https://www.orchestralibrary.com/reftables/rang.html and https://music-comp.org/sites/default/files/resources/1/Instrument%20Range%20and%20Score%20Layout.pdf. ↵

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was an Austrian composer. ↵

- Some great videos include https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNKaIe3VTy4, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JsVqb6PAA1k, and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNKaIe3VTy4. ↵

- Clara Kathleen Rogers (1844-1931) was an English-born American composer. ↵

- Florence Price (1887-1953) was an African-American composer. ↵

- Louise Reichardt (1779-1826) was a German composer and choral conductor. ↵

- Magdalena Casulana (1544–1583) was an Italian composer. Her madrigals were the first to be published by a woman in Italy. ↵

- Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) was a German composer. ↵

- Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) was a French composer and pianist. ↵

Instruments whose written pitch and concert pitch are the same.

The notes one sees or performs.

The note one hears.

Instrument whose written pitch (what you see or perform) is different than its concert pitch (what you hear).

How high or how low an instrument can sound or a person can sing

the most common part of a range in a song for vocalists

Sections of a musical range divided into low, middle, and high

How many melodies are performed and what else is happening at the same time

How many melodies are performed and what else is happening at the same time

When one (or all) instruments or voices perform the same melody at the unison or octaves

The unique quality of a musical sound

A type of musical texture in which there is one melody while other voices or instruments perform a subordinate role.

When more than one voice or instrument has the same melody overlapping one another, or different melodies occur at the same time

A secular polyphonic song for multiple voices without instruments. The text often plays a strong role, and its peak was during the Renaissance.

Opening melody of a fugue.

Second appearance of the melody of a fugue that occurs at a perfect fifth away from the subject (first appearance of the melody).

The continuation of the subject's melody when the answer begins

When the same melody occurs simultaneously in different voices, but with alterations or embellishments. It is seldom used in Western music.

Continually repeated rhythm or notes

Texture of music in which multiple melodies occur simultaneously.