5 Compound Meters

Now that you are familiar with beats and divisions within simple meters, we will learn about the role they play within compound meters.

5.1 INTRODUCTION

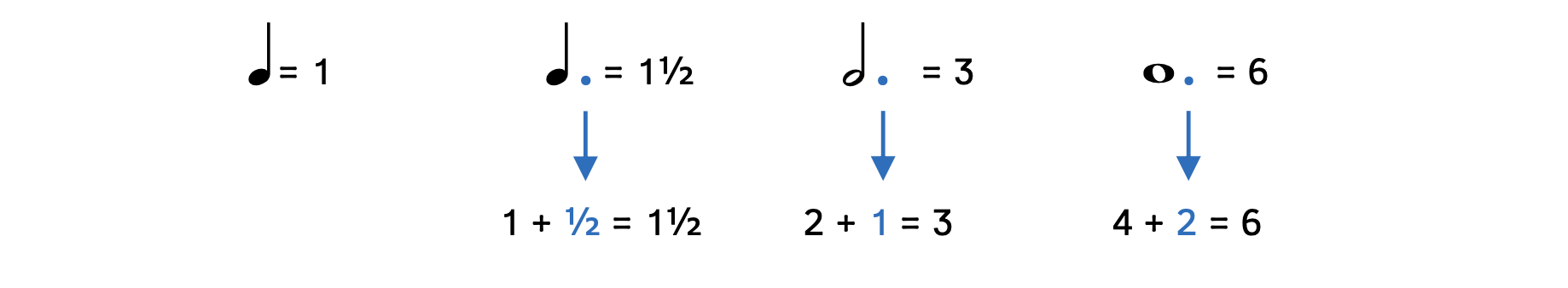

In Chapter 1, we learned that a dot after a note adds half the value of the note.

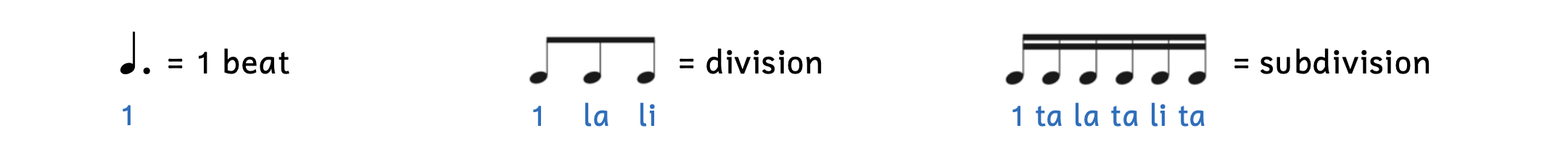

Example 5.1.1. Dotted notes

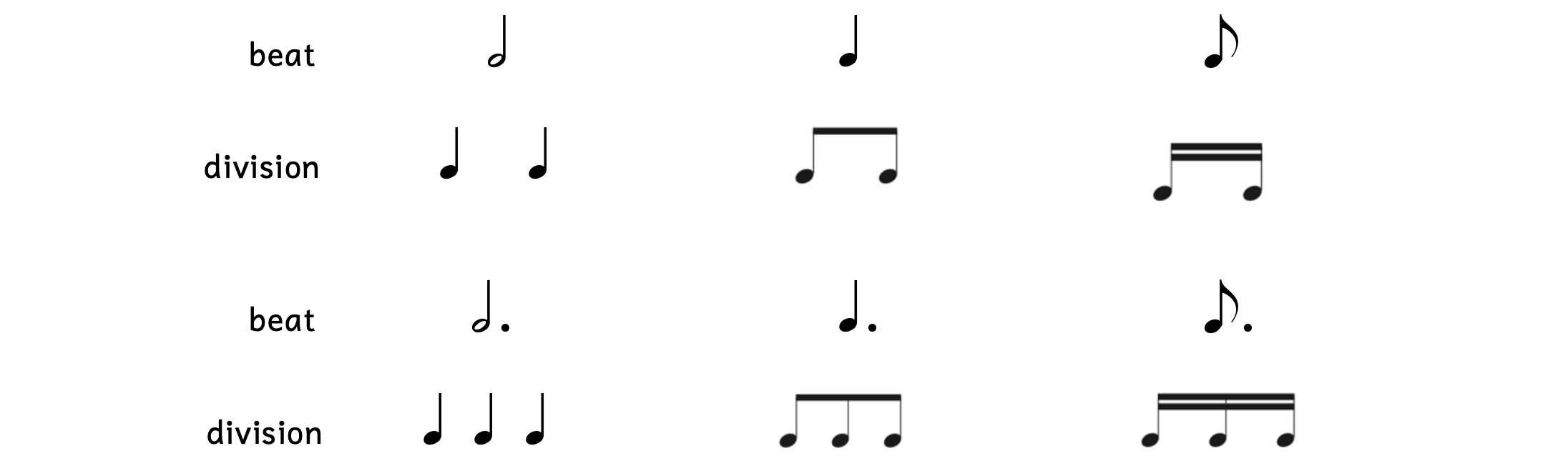

In Chapter 2, we learned that any note can equal one beat. If the note does not have a dot, it evenly divides into two; if the note is dotted, it equally divides into three.

Example 5.1.2. Divisions

In Chapter 3, we learned about simple meters: where the beat is a note without a dot and the beat divides evenly into two. In this chapter, we learn about compound meters, where the beat is a dotted note that divides equally into three.

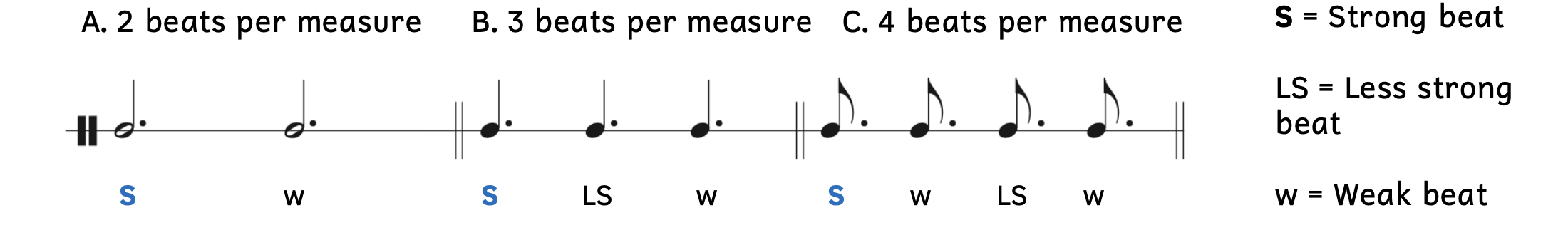

Just as with simple meters, not all beats are created equal, and beats that fall on the first beat are stronger than the others.

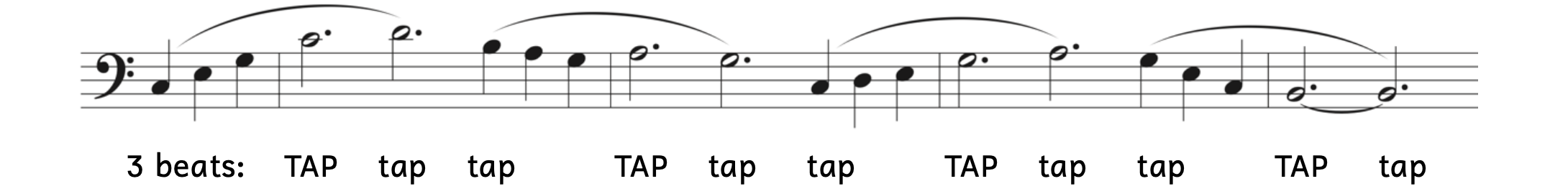

Example 5.1.3. Weighted beats

In Example 5.1.3, the downbeats are marked by the blue S’s.

- Example 5.1.3A:

- The dotted half note gets one beat and there are two beats per measure.

- When there are two beats per measure, the downbeat is strong (S) and the second beat is weak (w).

- Example 5.1.3B:

- The dotted quarter note gets one beat and there are three beats per measure.

- When there are three beats per measure, the downbeat is strong, the second beat is less strong (LS), and the third beat is weak.

- Example 5.1.3C:

- The dotted eighth note gets one beat and there are four beats per measure.

- Notice that the dotted eighth notes are not beamed together. This is because each dotted eighth note is equal to one beat. We only beam them when they combine to create one beat.

- When there are four beats per measure, the downbeat is strong, the third beat is less strong, and the second and fourth beats are weak.

Strong beats are accented while weak beats are unaccented. Tap your foot while listening to the next three examples.

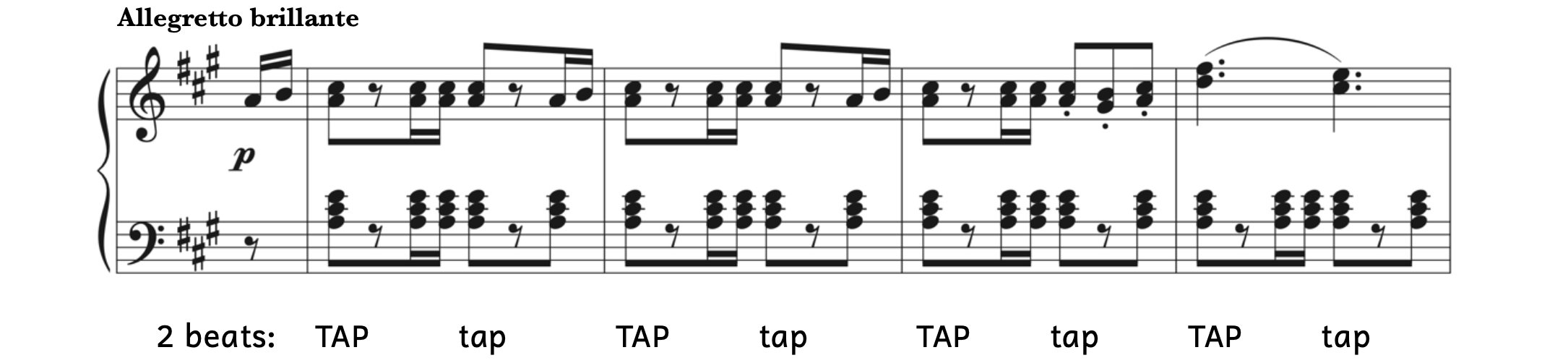

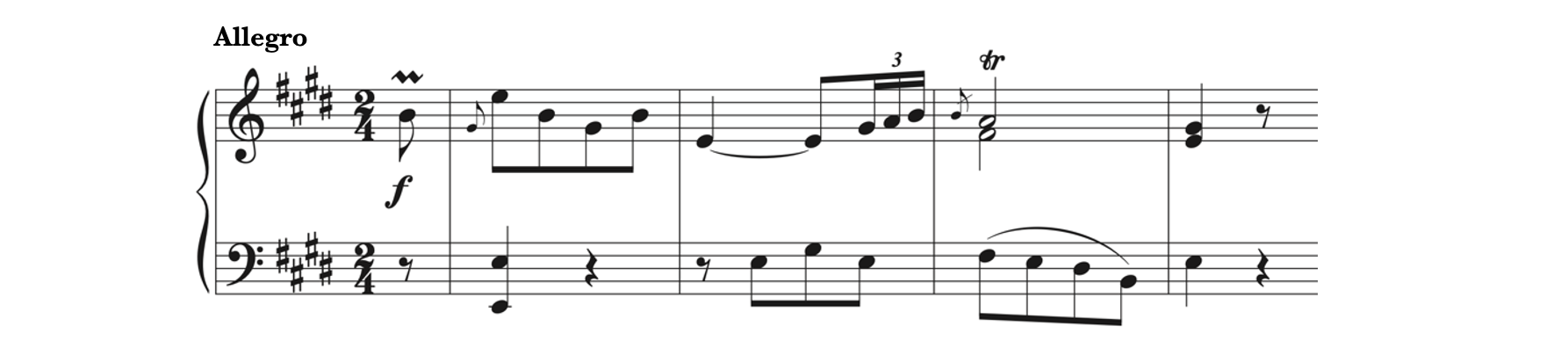

Example 5.1.4. Two beats per measure: Suppé[1], Light Calvary, Overture

- Example 5.1.4 is in A major and begins with an anacrusis.

- Remember that an anacrusis is not a complete measure, but only a note (or notes) that lead into the downbeat of the first measure. This is made clear by the rest in the bass clef. Normally, an entire measure of rest would require a whole rest. However, the rest is an eighth rest to accompany the two sixteenth notes in the treble clef.

- After the anacrusis, there are two beats per measure since you would tap your foot twice per measure. As usual, the downbeat is stronger than the second beat.

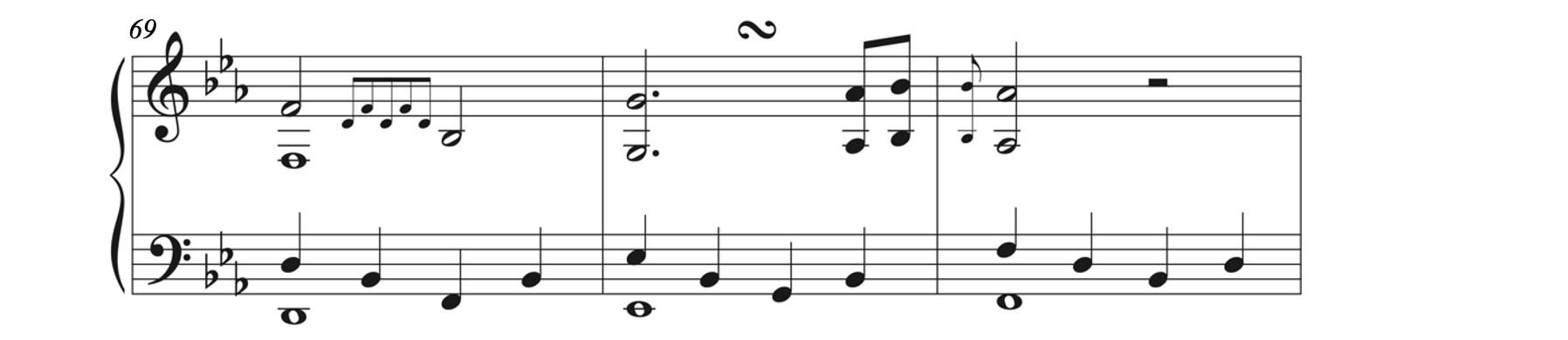

Example 5.1.5. Three beats per measure: “Morning Has Broken”

- Example 5.1.5 is in C major and also begins with an anacrusis.

- The pattern with the anacrusis repeats for each measure (instead of each beat, as in Example 5.1.4) and there are three beats per measure.

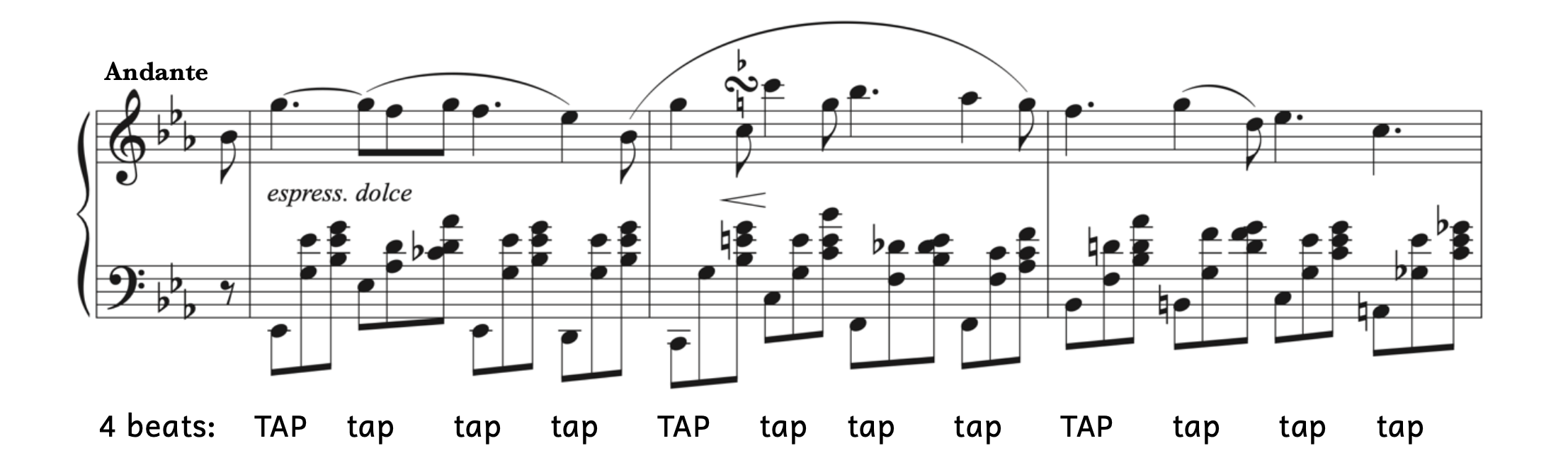

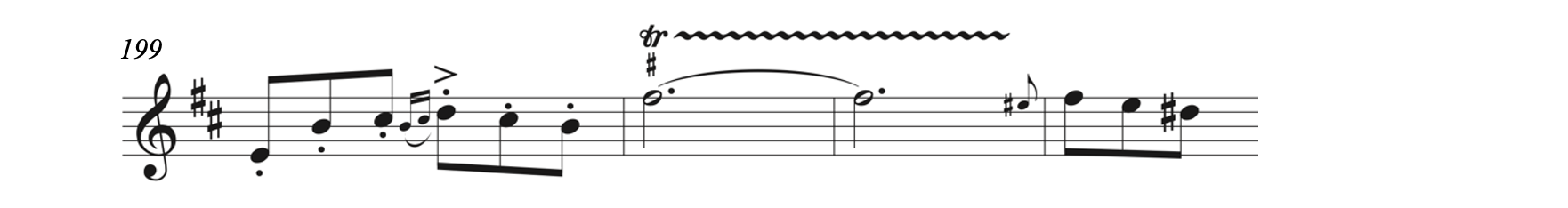

Example 5.1.6. Four beats per measure: Chopin[2], Nocturne, Op. 9, No. 2

- Example 5.1.6 begins in E

major. After the initial anacrusis, there are four beats per measure.

major. After the initial anacrusis, there are four beats per measure. - Due to the slow tempo of Chopin’s Nocturne, the divisions can be clearly heard and one may mistakenly tap their foot twelve times per measure.

Compound Meter

Compound meters have beats that are dotted notes and equally divide into three.

5.2 TIME SIGNATURES

Any dotted note can equal one beat, but the dotted half note, dotted quarter note, and dotted eighth note are most common. Beats are organized into groups with bar lines and groups of two, three, and four are most common.

Like simple meters, time signatures for compound meters are also two numbers above one another but the numbers require an entirely different interpretation.

Recall that for simple meters, the top number refers to how many beats per measure. The bottom number refers to what type of note get the beat. Most commonly, the top number is 2, 3, or 4 and the bottom number is 2, 4, or 8. This is not how the time signatures for compound meters are interpreted.

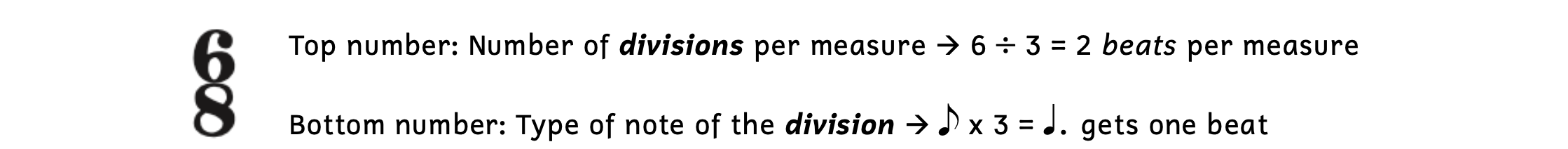

Example 5.2.1. Time signature for compound meters

- The top number of time signatures for compound meters refers to how many divisions (not beats) per measure.

- Since divisions for dotted notes are always in groups of three, we divide the top number by three to find how many beats there are per measure.

- In 6/8, the 6 means there are six notes in the division.

- Three notes in the division equals one beat, so six notes in the division equals two beats per measure.

- In other words, 6 divided by 3 = 2.

- There are most commonly two, three, or four beats per measure, so the top number will be 6 (two beats per measure), 9 (three beats per measure), or 12 (four beats per measure).

- Students often incorrectly say there are six beats per measure. This is wrong because there are six divisions per measure, but only two beats per measure.

- The bottom number of time signatures for compound meters refers to the type of note the division is (not the beat).

- For dotted notes, three divisions equal one beat, so we multiply the bottom note value by three to figure out what type of note gets one beat.

- In 6/8, the 8 means that the eighth note is the division (not the beat). To find the beat, we can add three eighth notes together (to equal a dotted quarter note) or multiply the eighth note by three (to equal a dotted quarter note).

- The dotted half note, dotted quarter note, and dotted eighth note are most commonly equal to one beat, so the bottom number is usually 4 (dotted half note beat), 8 (dotted quarter note beat), or 16 (dotted eighth note beat).

In one symbol, Example 5.2.1 tells us that there are two dotted-quarter-note beats in one measure.

Shortcut: Finding the Beat for Compound Time Signatures

A shortcut to finding what note gets one beat in compound meters is to think of the next higher-value note than the bottom number of the time signature and add a dot.

- If the bottom number is 16, it means the dotted eighth note gets the beat.

- If the bottom number is 8, it means the dotted quarter note gets the beat.

- If the bottom number is 4, it means the dotted half note gets the beat.

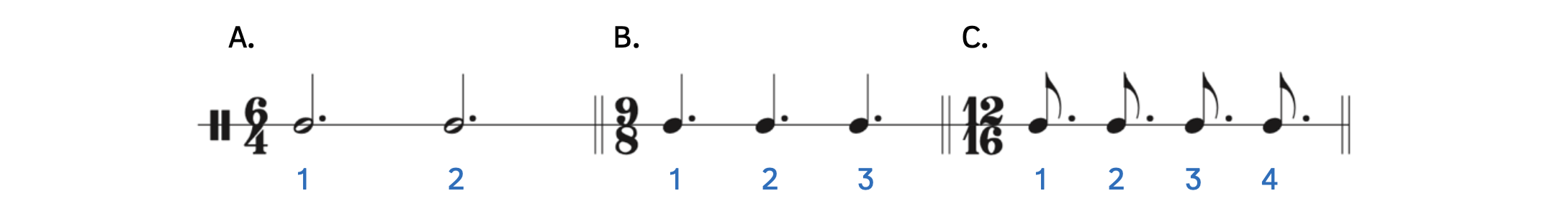

If we take the same models from Example 5.1.3 and add time signatures, we get Example 5.2.2.

Example 5.2.2. Added time signatures

- Example 5.2.2A: The time signature tells us there are two dotted-half-note beats per measure.

- Divide the top number 6 by three: there are two beats per measure (not six).

- The bottom number 4 represents a quarter note. Thus, the dotted half note gets one beat because the half note is the next higher note value.

- Example 5.2.2B: The time signature tells us there are three dotted-quarter-note beats per measure.

- Divide the top number 9 by three: there are three beats per measure (not nine).

- The bottom number 8 represents an eighth note. Thus, the dotted quarter note gets one beat because the quarter note is the next higher note value.

- Example 5.2.2C: The time signature tells us there are four dotted-eighth-note beats per measure.

- Divide the top number 12 by three: there are four beats per measure (not twelve).

- The bottom number 16 represents a sixteenth note. Thus, the dotted eighth note gets one beat because the eighth note is the next higher note value.

Recall that the rhythm syllables to count divisions of three (i.e., compound meters) are different than those to count simple meters.

Example 5.2.3. Dotted beat rhythm number system

We can take what we learned about divisions and subdivisions and fill these measures with different rhythms.

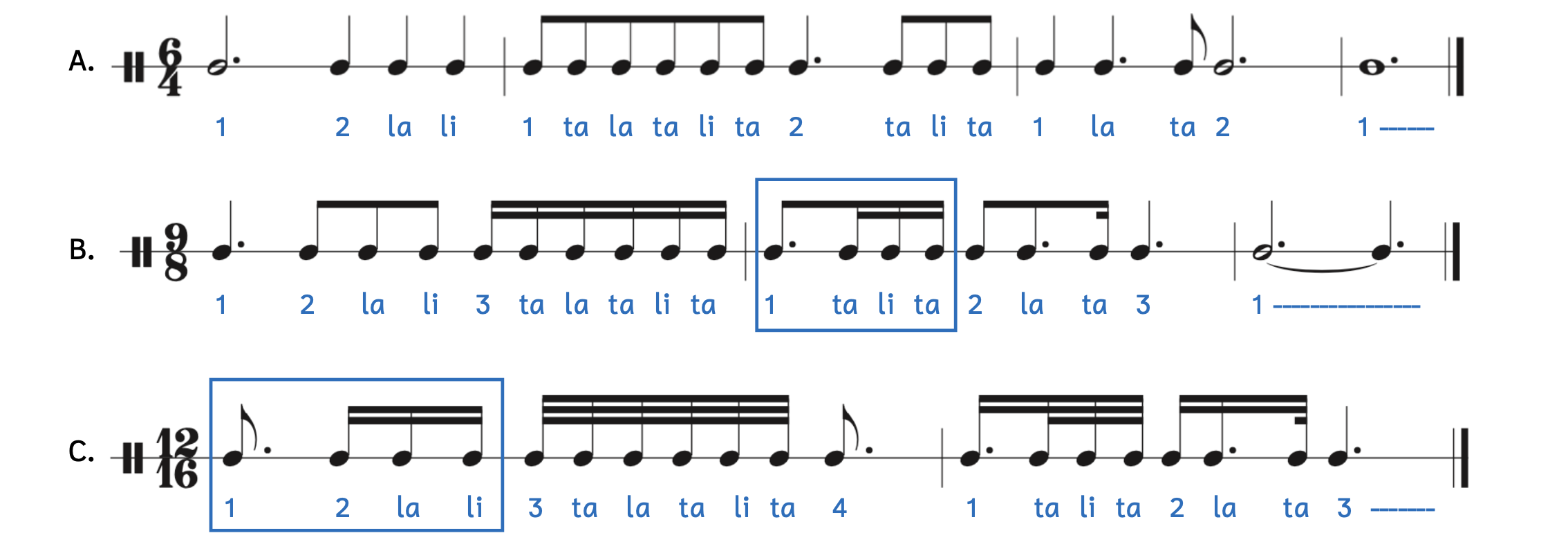

Example 5.2.4. Rhythms

- Example 5.2.4A:

- Since the division is three quarter notes, the dotted half note equals one beat and the subdivision is six eighth notes.

- In measure 2, there are six eighth notes beamed together. Because there are six notes beamed together, we immediately know that this is a subdivision and not a division.

- In measure 3, we cannot beam “1 la – ta” because the quarter note does not have a flag.

- In measure 4, the final note ends on the strong downbeat. There are dashes after the rhythm syllable “1” because it is held out beyond beat 2.

- Example 5.2.4B:

- Since the division is three eighth notes, the dotted quarter note equals one beat and the subdivision is six sixteenth notes.

- Notice how helpful the beaming is to distinguish beats.

- Since there are only three dotted-quarter-note beats per measure, we cannot end with a dotted whole note (because that would equal four dotted quarter notes). Instead, a dotted half note falls on the downbeat and ties to a dotted quarter note to fill the final measure.

- Example 5.2.4C:

- Since the division is three sixteenth notes, the dotted eighth note equals one beat and the subdivision is six thirty-second notes.

- The first eighth note is not beamed to the next three sixteenth notes because a dotted eighth note is equal to one beat.

- Compare the two boxed areas in Example 5.2.4. The note values are the same (dotted eighth note + three sixteenth notes), but because the note values of the beat differ, they are written (and counted) differently.

- This example does not end on the downbeat, but on beat 3. This is okay because beat 3 is still a strong beat (but less strong than the downbeat).

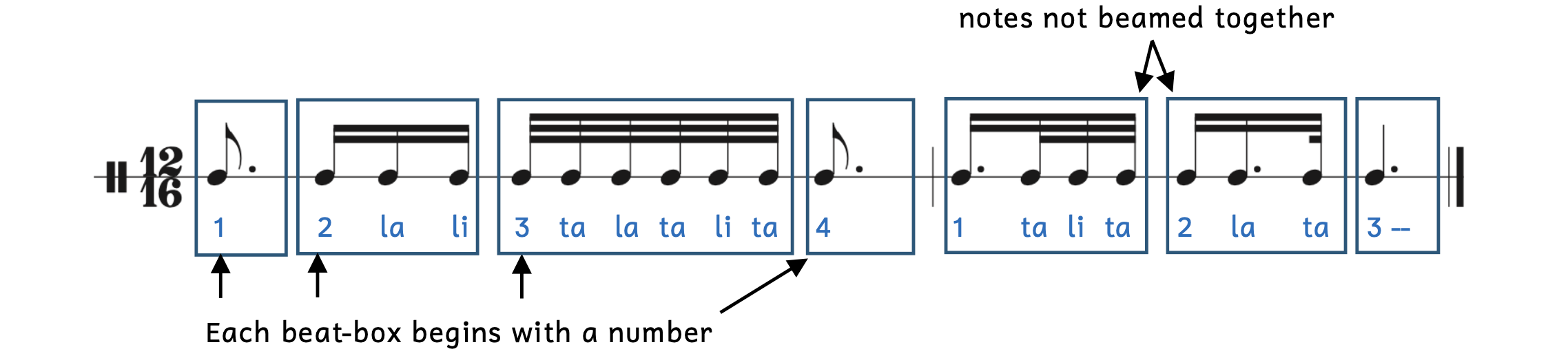

When writing rhythms correctly within a time signature, many students find it helpful to box each beat, then write the beaming correctly within each beat.

Example 5.2.5. Beat-boxes

When we box rhythm into separate beat-boxes, the ability to read music quickly becomes much easier.

- Each box represents a beat and each box begins with a number.

- Notice how there are no beams across beat-boxes.

Remember that rests are the same as notes, but represent silence. Any notes can be substituted with its equivalent rest.

Unlike simple meters, there are no time signatures in compound meter that have their own symbol.

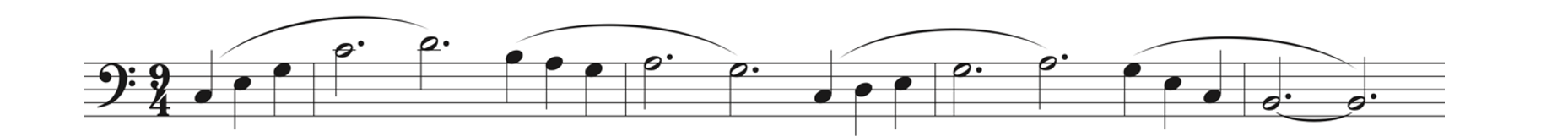

Let us return to Examples 5.1.4, 5.1.5, and 5.1.6 and see which time signatures are used.

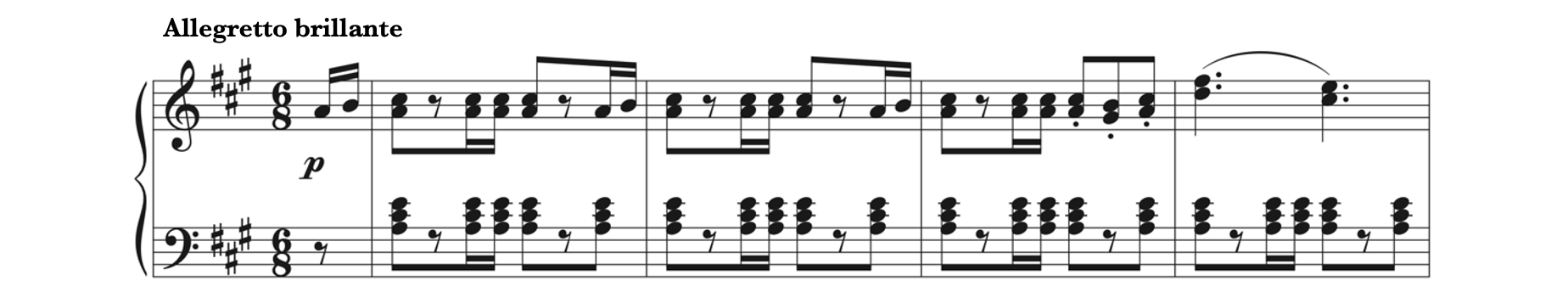

Example 5.2.6. Suppé, Light Calvary, Overture

Recall that we only tapped our foot twice per measure (Example 5.1.4). This results in a dotted quarter note equaling one beat and the division of three eighth notes. Therefore, the time signature is 6/8.

Example 5.2.7. “Morning Has Broken”

In Example 5.1.5, we discovered that we tapped our foot three times per measure in “Morning Has Broken” (Example 5.2.7). Because there are three beats per measure, a dotted half note gets one beat. As a result, the time signature is 9/4.

Example 5.2.8. Chopin, Nocturne, Op. 9, No. 2

In Example 5.1.6, we established that despite the slow tempo, we tapped our foot four times per measure. This gives rise to a dotted-quarter-note beat. Thus, as shown in Example 5.2.8, the time signature is 12/8.

Compound Time Signatures

The top number: Divide by three to find how many beats per measure.

- 6 means two beats per measure

- 9 means three beats per measure

- 12 means four beats per measure

The bottom number: Multiply by three to find what type of note gets the beat.

- 4 means a dotted half note gets one beat

- 8 means a dotted quarter note gets one beat

- 16 means a dotted eighth note gets one beat

Although it is possible to have different numbers on the top or on the bottom, these are the most common ones.

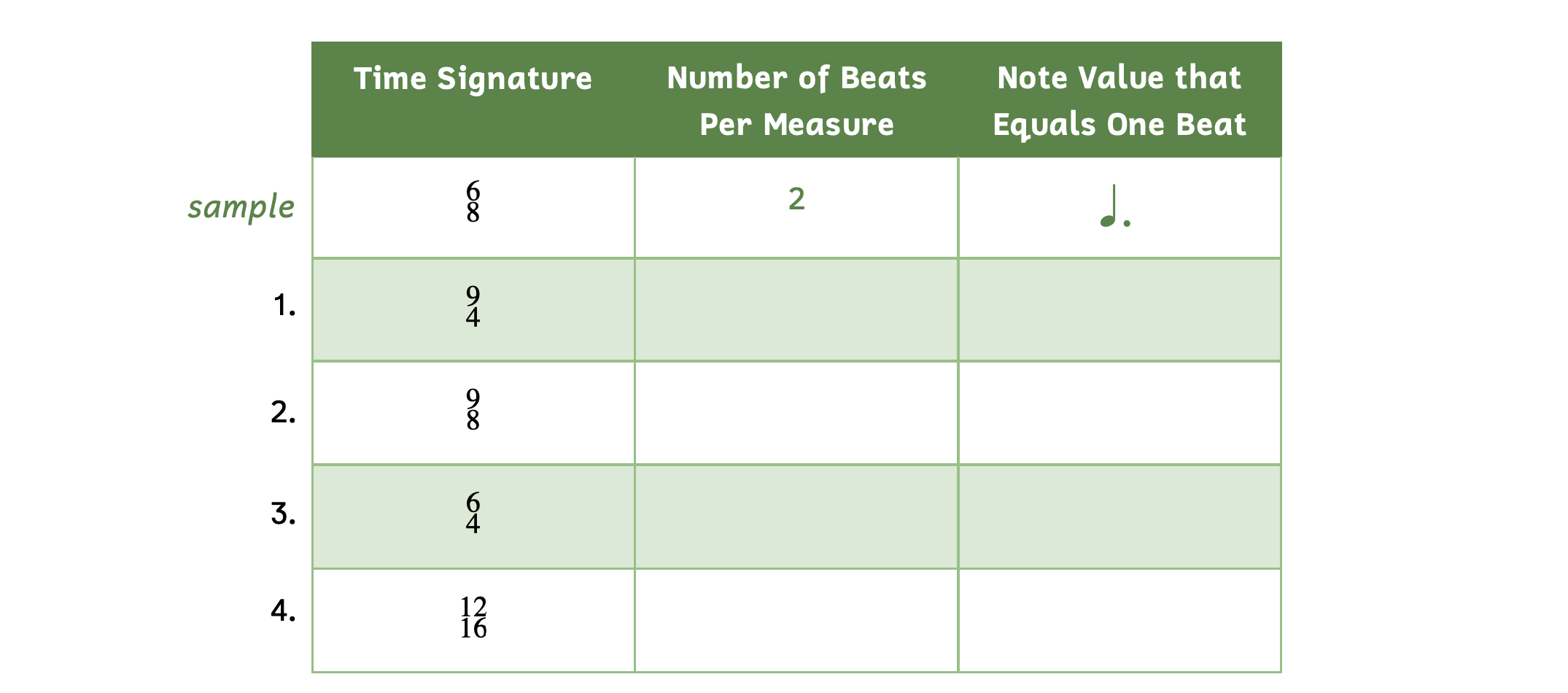

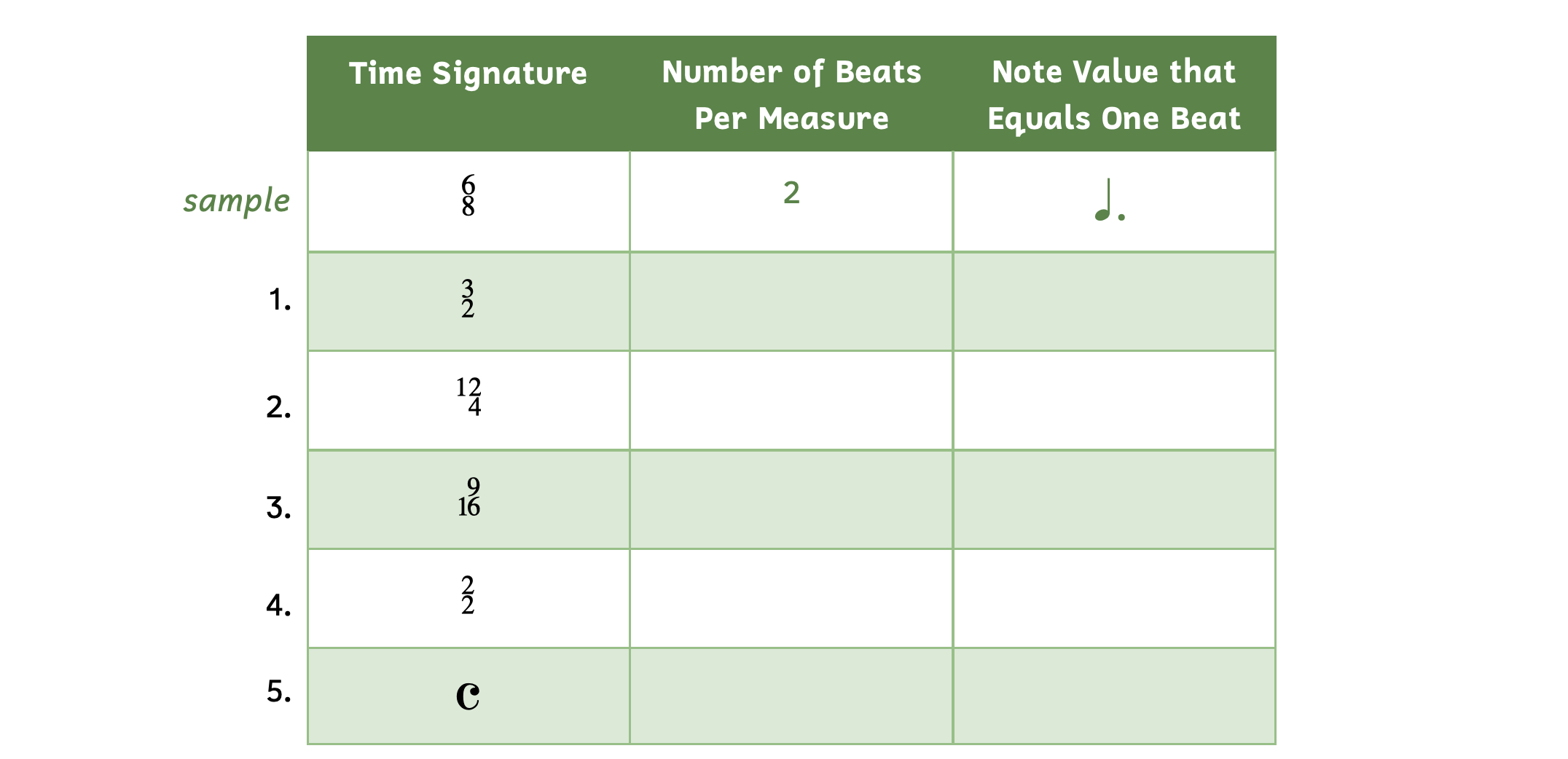

Practice 5.2A. Interpreting Compound Time Signatures

Directions:

- Complete the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) There are 3 beats per measure. The dotted quarter note receives one beat.

3) There are 2 beats per measure. The dotted half note receives one beat.

4) There are 4 beats per measure. The dotted eighth note receives one beat.

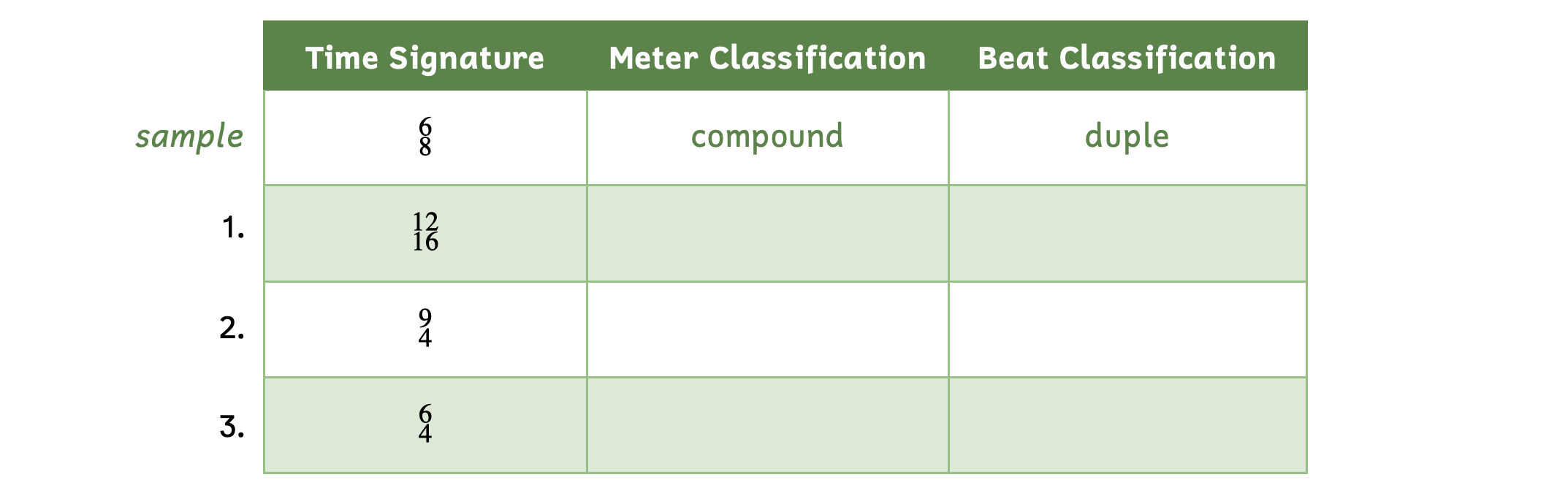

Practice 5.2B. Assigning Time Signatures in Compound Meters

Directions:

- Listen to the following melodies and write the most likely time signature onto the staff.

1. Ignore the anacrusis. Wagner[3], Die Walküre, “Ride of the Valkyries,” Act III, Scene i

2. Ignore the anacrusis. Gounod[4], Funeral March of a Marionette

3. Mozart[5], Requiem, Lacrimosa

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) 6/8

3) 12/8

5.3 METER AND BEAT CLASSIFICATIONS

We learned that a simple meter is a meter classification where the beat evenly divides into two. When the top number of a time signature is 2, 3, or 4, it tells us the meter is simple and that there are two, three, or four beats per measure. Having two, three, or four beats per measure refers to a beat classification of duple, triple, or quadruple. We combine meter and beat classifications to describe time signatures.

We do the same with compound meters. The meter classification of a dotted-note beat that divides equally into three is compound. When the top number of a compound time signature is 6, 9, or 12, the beat classification tells us it is compound and that there are two, three, or four beats per measure: duple, triple, or quadruple.

Example 5.3. Meter and beat classification

Notice that the bottom number of the time signature does not matter when we refer to meter and beat classifications.

- Top number 6 = compound duple

- Top number 9 = compound triple

- Top number 12 = compound quadruple

Refer back to Examples 5.2.6-5.2.8:

- Example 5.2.6: Suppé’s Overture is in compound duple because the time signature is 6/8.

- Example 5.2.7: “Morning Has Broken” is in compound triple because of the 9/4 time signature.

- Example 5.2.8: Chopin’s Nocturne is in compound quadruple because the time signature is 12/8.

Meter and Beat Classification

If the top number of a time signature is 6, 9, or 12, the meter and beat classification is compound duple, compound triple, or compound quadruple, respectively.

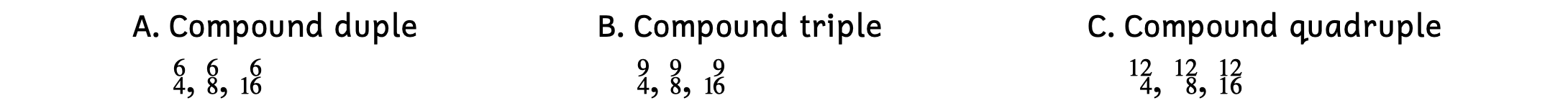

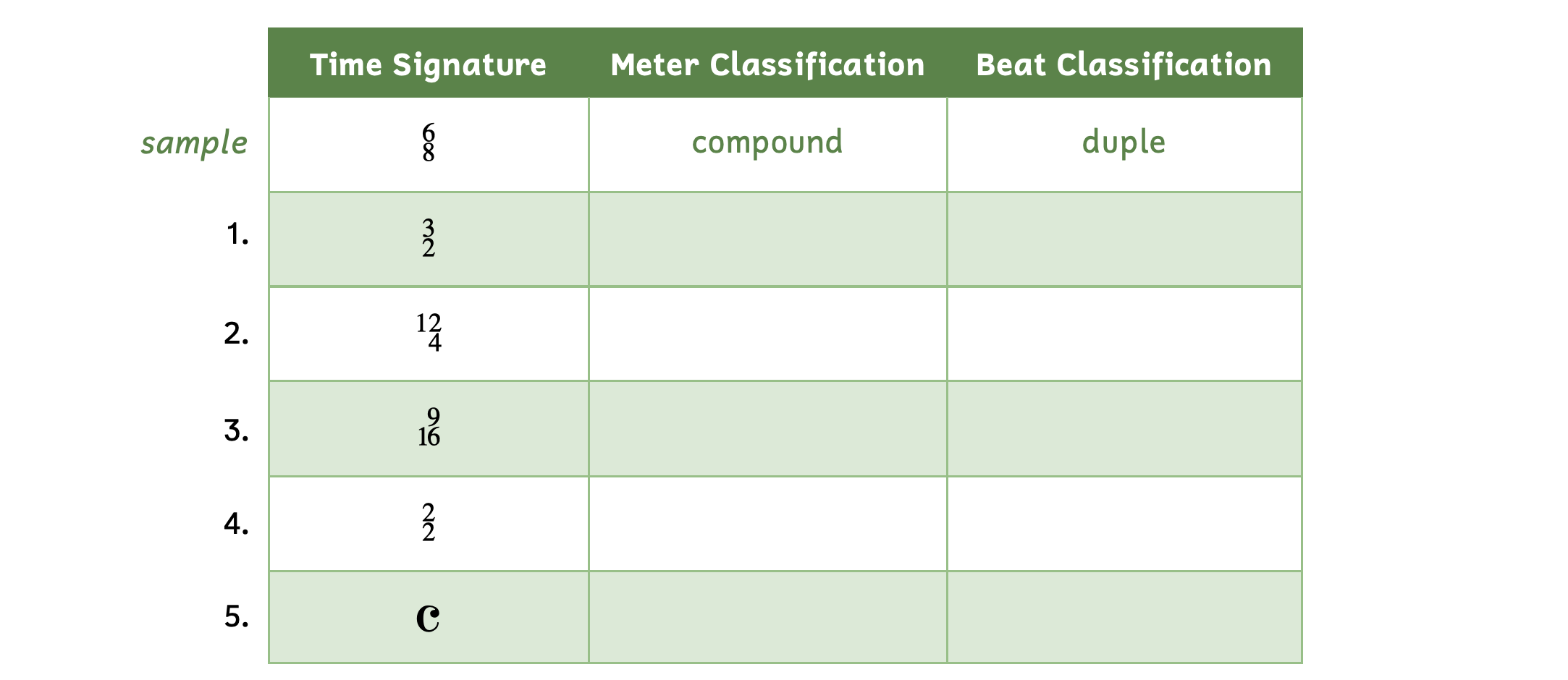

Practice 5.3. Classifying Compound Time Signatures

Directions:

- Fill in the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) compound triple

3) compound duple

5.4 SIMPLE V. COMPOUND METERS

Now that we have learned about simple meters (Chapter 3) and compound meters, let us review by placing them side by side.

- What makes the meter simple or compound?

-

- Simple: Beat is a note without a dot that is evenly divided into two.

- Compound: Beat is a dotted note that is equally divided into three.

- Top number of the time signature:

-

- Simple: Top number is 2, 3, or 4 and refers to the number of beats per measure.

- Compound: Top number is 6, 9, or 12 and refers to the number of divisions per measure. To find the number of beats, divide the top number by three.

- Bottom number of the time signature:

-

- Simple: Bottom number is a note value (usually 2, 4, or 8) and refers to what type of note gets one beat.

- Compound: Bottom number is a note value (usually 4, 8, or 16) and refers to what type of note get the division.

- To find the note that gets the beat, go to the next higher note value and add a dot.

- How do you know when a time signature is simple or compound?

-

- Look at the top number:

- If the top number is 2, 3, or 4, it is simple.

- If the top number is 6, 9, or 12, it is compound.

- Look at the top number:

- How do you know when the music you are listening to is simple or compound?

-

- One technique you can use is while you are tapping your foot to the beat, tap your finger along with the division.

- If you can tap your finger evenly twice per beat, the meter is simple.

- If you can tap your finger evenly three times per beat, the meter is compound. In addition, compound meters often create a swinging feel.

- One technique you can use is while you are tapping your foot to the beat, tap your finger along with the division.

Let us return to “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” and figure out the time signature.

Example 5.4.1. Finding the time signature: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”

- We immediately know “Twinkle, Twinkle” is in a simple meter because there are no dotted notes and no divisions of three.

- Be careful, however, because dotted notes do exist in simple meters. When you encounter a dotted note in simple meters, it either has a longer duration (e.g., dotted half note) or it will be paired with a note half the note’s value (e.g., dotted eighth note + sixteenth note).

- Once we establish it is simple, we need to figure out how many beats there are per measure.

- There are clearly four quarter notes per measure, so the time signature could be 4/4.

- However, we see from the pattern of notes (two repeated Cs, two repeated Gs, etc.) that the first note of each pair is stronger than the next. This would imply that the quarter note is not the beat, but the division. In that case, the time signature would be 2/2. Either time signature would be acceptable since in 4/4, beats 1 and 3 are stronger beats.

Observe how “Twinkle, Twinkle” would appear in a compound meter.

Example 5.4.2. “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” in compound meter

- We immediately know Example 5.6.2 is in a compound meter because there are dotted note beats and divisions of three.

- Since the dotted quarter note gets the beat, this means the division is made of three eighth notes. Therefore, the bottom number of this compound time signature would be 8.

- Based on the dotted quarter note beat, we also discover there are two beats per measure.

- In compound meters, when there are two beats per measure, the top number is 6. Therefore, the time signature would be 6/8.

Simple Versus Compound Meters

- Look at the top number of the time signature: 2, 3, or 4 means it is a simple meter and 6, 9, or 12 means it is a compound meter.

- Look for the beat and division: If you see a dotted-note beat and divisions of three, it is compound.

- Listen for the division: Compound meters divide into three and often create a swinging feel.

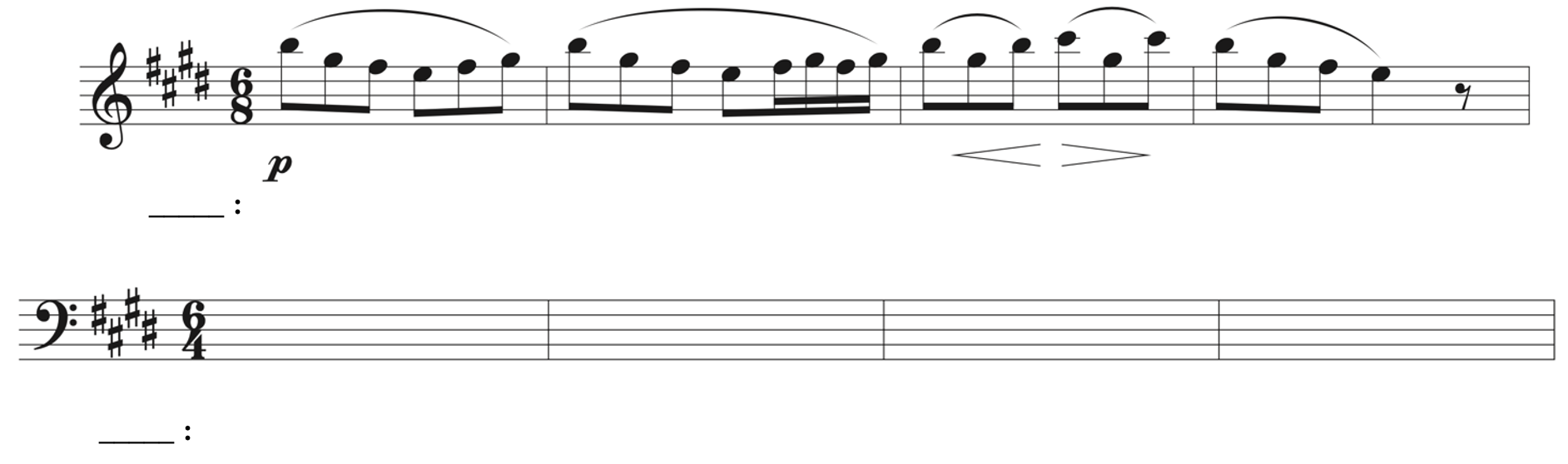

Practice 5.4A. Choosing Time Signatures

Directions:

- Look for clues in the following examples and write what you think the time signature would be.

- Under the musical example, write the key.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) Time signature is common time (or 4/4). Key is E major.

3) Time signature is 3/4. Key is B major.

Practice 5.4B. Interpreting Time Signatures

Directions:

- Complete the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) There are 4 beats per measure. The dotted half note equals one beat.

3) There are 3 beats per measure. The dotted eighth note equals one beat.

4) There are 2 beats per measure. The half note equals one beat.

5) There are 4 beats per measure. The quarter note equals one beat.

Practice 5.4C. Classifying Time Signatures

Directions:

- Complete the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) compound quadruple

4) simple duple

5) simple quadruple

5.5 THE AMBIGUOUS “3”

We learned that the top number of simple meters tells us how many beats are in each measure (e.g., 2, 3, or 4). Observe the following example in simple triple.

Example 5.5.1. Farrenc[6], Trio for Flute, Cello, and Piano, ii – Andante

Although there are dotted notes, the dotted eighth notes are paired with and beamed with a sixteenth note to form one beat. The quarter note equals one beat and there are three beats per measure (clearly seen in measure 3), resulting in a simple triple meter. The Andante tempo emphasizes the triple meter, as you would tap your foot three times per measure. The time signature of 3/4 confirms the simple triple meter.

Now listen to Example 5.5.2, which also appears to be in simple triple.

Example 5.5.2. Farrenc, Trio for Flute, Cello, and Piano, iii – Scherzo. Vivace

How many times per measure did you tap your foot while listening to Example 5.5.2? Most likely, you only tapped your foot once per measure since the tempo (Vivace) is so fast. In instances like this, 3/8 is not a simple meter, but a compound meter.

The top number of compound meters tells us how many divisions are in each measure. Since compound meters have divisions of three, the top number is always divisible by three (e.g., 6, 9 or 12). However, the number 3 is also divisible by three.

If we divide the top number 3 by three, it implies the time signature is compound and that there is only one beat per measure, making the meter and beat classification compound single.

Deciding when a time signature with the top number 3 is simple or compound can be challenging. If Example 5.5.2 were played slightly slower, one may tap their foot three times per measure, making the example simple triple.

The Ambiguous “3”

Depending on the tempo, time signatures with the top number of 3 can either be simple triple or compound single.

Practice 5.5. Identifying Simple Triple or Compound Single

Directions:

- Would you perform the following examples as simple triple or compound single? Write your answer in the blank.

- Below the musical example, write the key.

1. Wieck Schumann[7], Three Preludes and Fugues, Op. 16, Fugue No. 2: ______________________________

2. Wieck Schumann, Caprice, Op. 2, No. 8: ______________________________

3. Wieck Schumann, Caprice, Op. 2, No. 2: ______________________________

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) compound single – E

3) compound single – D major

5.6 TRANSPOSITION: RHYTHM

Some students are most comfortable writing and reading compound meters where the dotted quarter note is the beat. However, when the beat is a dotted half note or dotted eighth note, they sometimes struggle. One strategy those students can utilize is using rhythmic transposition to temporarily think of the time signature where a dotted quarter note equals a beat. Transposition is when you change all notes equally by the same proportion. Compare the examples below.

Example 5.6. Rhythmic transposition

We know all the notes in Examples 5.6A, B, and C are proportionally equal because the rhythm syllables are the same.

There is an easy shortcut for doubling or halving dotted notes:

- To double a dotted note, write a dotted note of the next higher value (e.g., doubling a dotted quarter note is a dotted half note).

- To halve a dotted note, write a dotted note of the next smaller value (e.g., halving a dotted quarter note is a dotted eighth note).

Rhythmic Transposition

When transposing rhythms, compare note values of the beats and apply that same proportion to the new time signature.

Practice 5.6. Transposing Melodies and Time Signatures

Directions:

- Transpose the rhythms into the given time signature and key signature.

- Fill in the blanks with the correct major key.

- Keep all pitches, articulations, and dynamics.

1. Grieg[8], Peer Gynt, “Morning Mood”

2. “Home on the Range”

Click here to watch the tutorial.

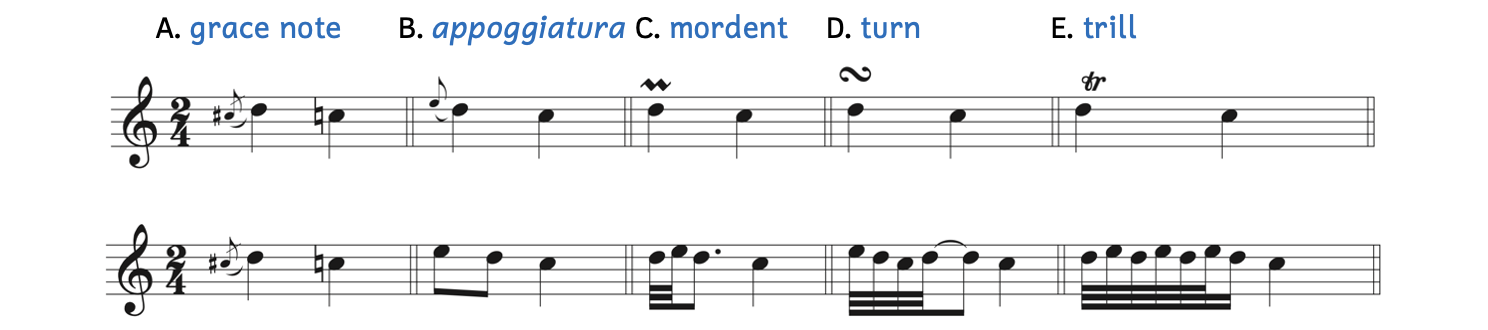

5.7 ORNAMENTS

In this chapter, you may have noticed some unfamiliar symbols (see Example 5.2.8 and Practice 5.2B.2). These unfamiliar symbols are called musical ornaments. A musical ornament, or embellishment, is an added note or notes that decorates the main note. It can be represented by a small note or by a symbol.

There are more ornaments than the ones in Example 5.7.1 and ornaments have changed meaning throughout the centuries. In this chapter, we will only cover these five ornaments and the most common ways to perform them.

Example 5.7.1. Ornaments

The first line in Example 5.7.1 shows how the ornaments appear and the second line shows how the ornaments are to be performed.

- Example 5.7.1A: The grace note, also known as the acciaccatura, comes from the Italian word “acciaccare,” which means “to crush.” The grace note is a small note with a slash that is written before a note that falls on a beat. The grace note is to be played quickly and right before the main note falls on the beat. There can be more than one grace note before the main note, but in those cases, there is usually no slash on the small notes.

- Example 5.7.1B: The appoggiatura looks like a grace note, but there is no slash. It is to be performed very differently than the grace note. The small note falls on the beat and is half the duration of the next main note. There can be more than one appoggiatura before the main note.

- Example 5.7.1C: The mordent has several variations. The mordent can fall before the beat or on the beat. If there is a vertical line through the middle of the mordent, it becomes a lower mordent where the notes in Example 5.7.1C would be D-C-D instead of D-E-D.

- Example 5.7.1D: The turn also has several variations. Like the mordent, it can fall before the beat or on the beat. Also like the mordent, if there is a line through the middle of the turn, the turn first descends then ascends. Example 5.7.1D would be C-D-E-D instead of E-D-C-D.

- Example 5.7.1E: The trill can vary in duration and can even continue for multiple measures. Trills repeat alternating notes.

We will now look at some ornaments in context.

Example 5.7.2. Ornaments: Martinez[9], Piano Sonata in E Major, i – Allegro

- Example 5.7.2 begins with a mordent, which would be played B–C

–B.

–B. - In measure 1, the appoggiatura indicates that the G

falls on the downbeat, and the G

falls on the downbeat, and the G and E are played as two sixteenth notes.

and E are played as two sixteenth notes. - The grace note in measure 3 occurs before the downbeat and the trill on the A lasts the entire measure.

- The number “3” in measure 2 represents a triplet, which we will learn about in a later chapter.

Example 5.7.3. Ornaments: Martinez, Piano Sonata in A Major, i – Allegro

- Example 5.7.3 begins with a lower mordent, which would be played A–G

–A. The lower mordent has a vertical line in the middle of it (compare to the mordent in Example 5.7.2).

–A. The lower mordent has a vertical line in the middle of it (compare to the mordent in Example 5.7.2). - In measure 2, the appoggiatura results in E performed as an eighth note that falls on the second beat.

- As a result, the trill only lasts for half a beat.

Earlier in this chapter, we came across a turn.

Example 5.7.4. Turn: Chopin, Nocturne, Op. 9, No. 2

The turn in measure 2 has a flat above it and a natural sign below. These accidentals apply to notes in the turn: the pitches are D![]() –C–B

–C–B![]() –C. Turns can also occur between notes.

–C. Turns can also occur between notes.

As mentioned earlier, there can be more than one grace note before a main note. One famous piece of music uses multiple graces notes.

Example 5.7.5. Grace notes: Mendelssohn[10], Spring Song

Example 5.7.5 includes numerous grace notes. However, because there is more than one grace note preceding each main note, the grace notes do not have slashes. They are still meant to be played like grace notes (and not appoggiaturas), so that all the little notes are performed before the main note, which falls on the beat.

Ornaments have changed meaning throughout the centuries; a mordent in 1750 may not be performed the same as a mordent in 1880. Moreover, individual performers may interpret ornaments differently. For the scope of this theory book, we will not go into detail about the many variations on how these symbols can be performed, but simply that they are decorations and do not alter the analysis. This section gives you the basics of five common musical ornaments.

Musical Ornaments

A musical ornament, or embellishment, is an added note or notes that decorates the main note. It can be represented by a small note or by a symbol

Practice 5.7. Identifying Musical Ornaments

Directions:

- Identify and label all musical ornaments.

- Briefly explain how each ornament should be performed.

1. Montgeroult[11], Piece for Piano, Op. 3, i – Adagio non troppo

2. Lang[12], Mazurka, Op. 49, No. 2

3. Röntgen-Maier[13], Violin Sonata in B Minor, i – Allegro

Click here to watch the tutorial.

5.8 ENDINGS

We have learned about three types of bar lines.

- Single bar line: Also known as simply “bar line,” the single bar line separates measures.

- Double bar line: With its two closely-placed fine bar lines, the double bar line is often used in examples and exercises to distinguish measures or sections from one another.

- Final double bar line: The final double bar line also has two closely-placed bar lines, but the first line is fine and the second is thick. It is used to mark the end of a piece or example.

In addition to the double bar line, repeat signs may be added to tell musicians to play specific sections (or an entire piece) again.

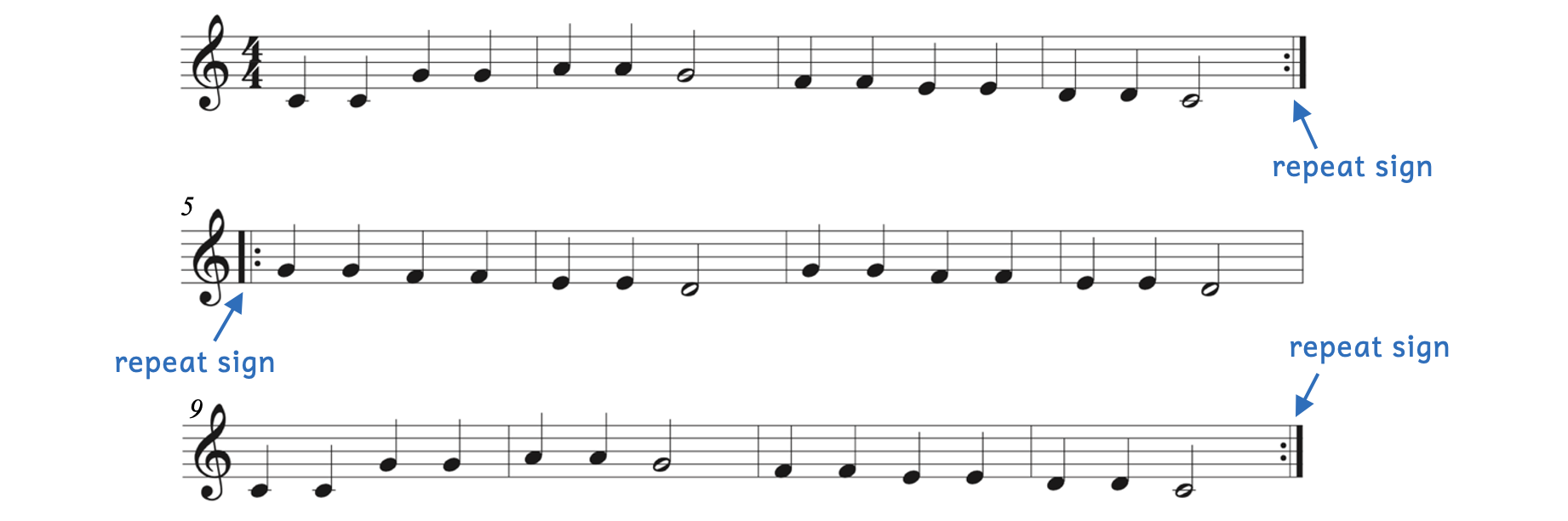

Example 5.8.1. Repeat signs

The repeat sign consists of two dots that sit in the second and third spaces of the staff. The dots lie within the inside of final double bar lines. Notice that at measure 5, the double bar lines are reversed, where the thicker line appears first.

Example 5.8.1 would be read like this:

- Read measure 1 to measure 4, then repeat measure 1 to measure 4.

- Read measure 5 to the end, then repeat measure 5 to the end.

Repeat signs can have a first and second ending.

Example 5.8.2. First and second endings

Example 5.8.2 would be read like this:

- Read measure 1 to measure 4, which is the first ending. Then return to the beginning.

- Read measure 1 to measure 3, then skip the first ending. Go directly to the second ending.

- There will be a total of eight measures.

Another common sign you may encounter is D. C. al Fine (da capo al fine). The words “da capo” mean “from the head” and “al fine” mean “to the end,” so you would go back to the beginning and stop at the final double bar line.

Example 5.8.3. D. C. al Fine

Example 5.8.3 would be read like this:

- Read measure 1 to measure 8, then return to the beginning (da capo).

- Read measure 1 to measure 4 (al fine).

There is no final double bar line at measure 8 because measure 8 is not the end: measure 4 is the end. There is only a double bar line at measure 8, and the final double bar line is at measure 4.

In addition to D. C. al Fine, you may also see D. S. al Fine (dal segno al fine). The words “dal segno” mean “from the sign,” so rather than returning back to the beginning, you return to the sign.

Example 5.8.4. D. S. al Fine

Example 5.8.4 would be read like this:

- Read measure 1 to measure 8, then return to the sign (segno).

- Read measure 3 to measure 4 (al fine).

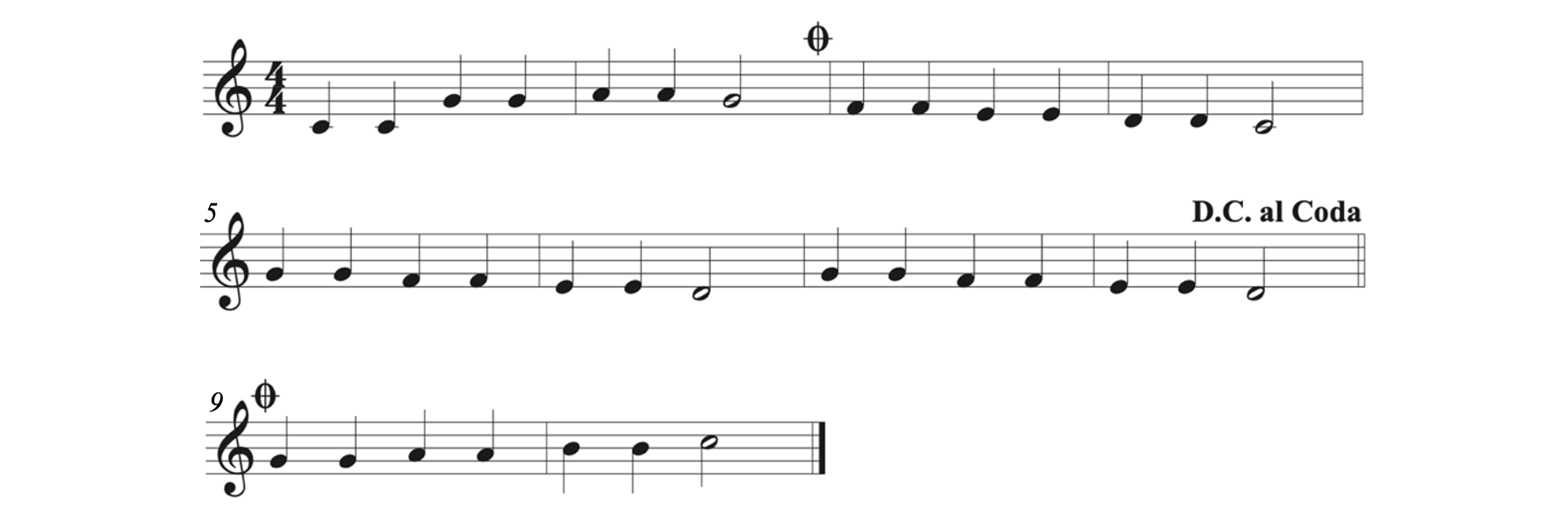

Another variation includes D. C. al Coda (da capo al coda). At D.C. al Coda, return to the beginning (da capo) until the coda sign (al coda). Then jump to the other coda sign until the end.

Example 5.8.5. D. C. al Coda

Example 5.8.5 would be read like this:

- Read measure 1 to measure 8, then return to the beginning (D.C.).

- Read measure 1 to measure 2, then jump to the coda sign (measure 9).

- Read measure 9 to measure 10.

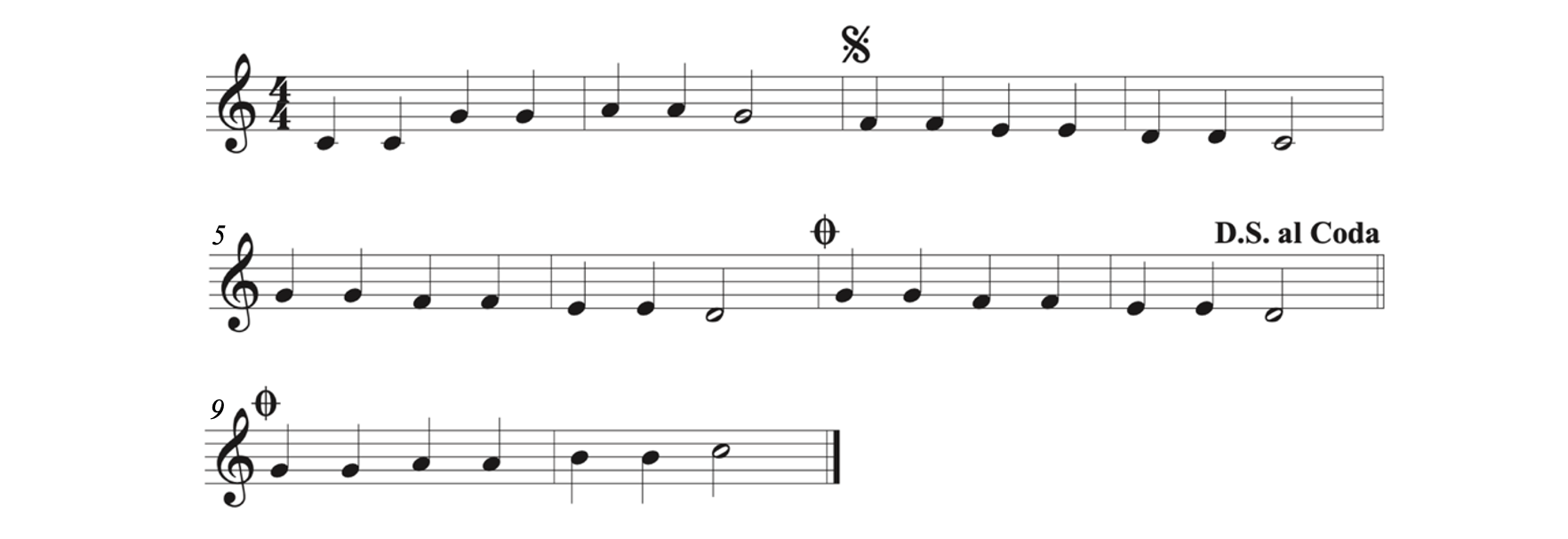

Both the segno and coda signs may be used in D. S. al Coda (dal segno al coda).

Ex. 5.8.6. D. S. al Coda

Example 5.8.6 would be read like this:

- Read measure 1 to measure 8, then return to the sign (measure 3).

- Read measure 3 to measure 6, then jump to the coda sign (measure 9).

- Read measure 9 to measure 10.

The variety of endings may seem confusing at first, but sometimes multiple pages of music are repeated and it is easier to simply add one of the labels from this section.

Endings

There are several different ways of ending in addition to reading straight through the music until the final double bar line, including repeat signs and descriptives words such as D.C. al Fine.

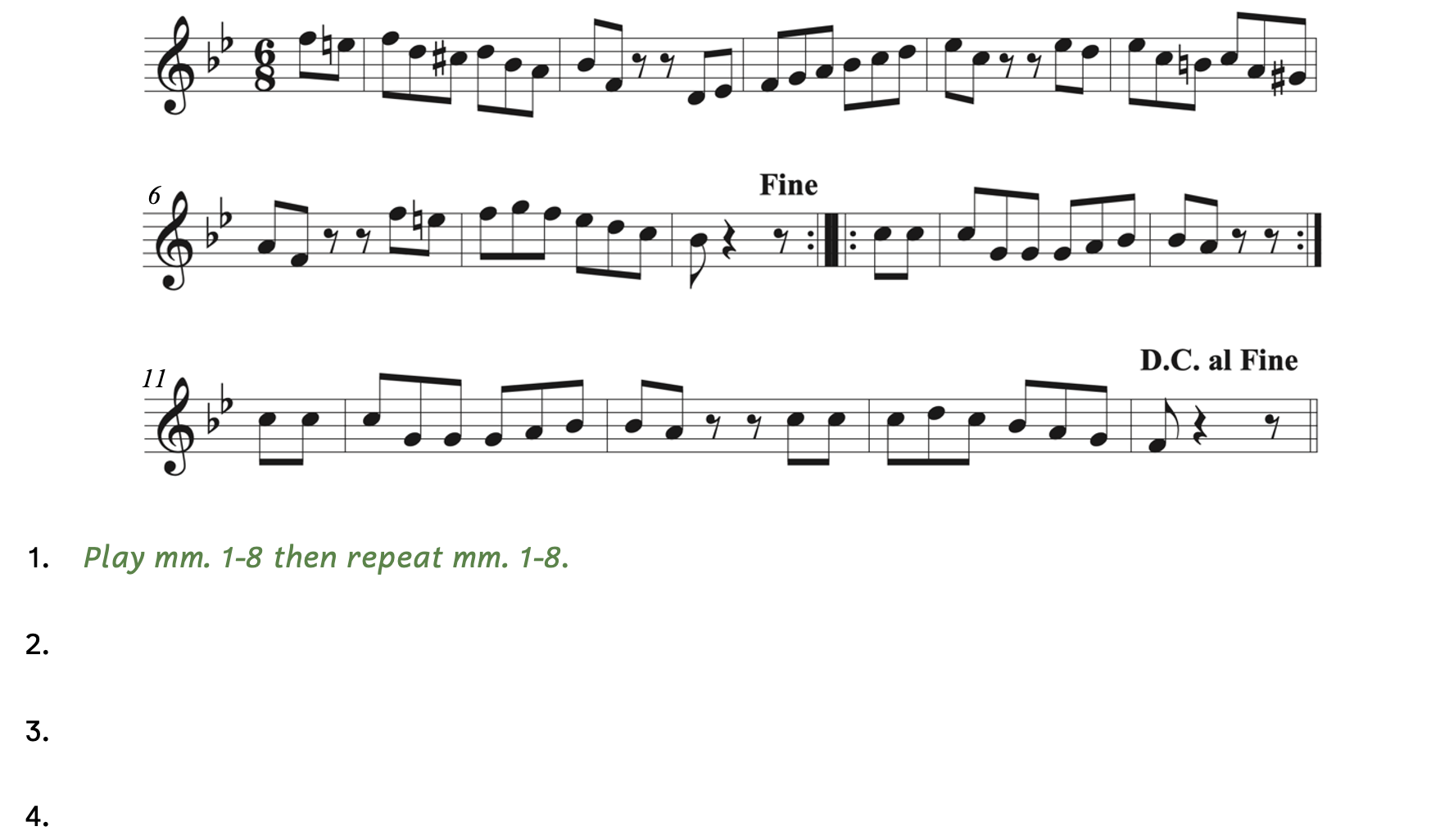

Practice 5.8. Navigating Repeats and Musical Direction

Directions:

- List how you would read the following example (see sample below).

- Remember that the anacrusis does not count as a measure.

“Jarabe Tapatio,” Mexican Hat Dance

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) Play measures 9-10 then repeat measures 9-10.

3) Play measures 11-14 then return to start.

4) Play measures 1-8 then repeat mm. 1-8 (repeat is optional).

SUMMARY

-

-

- Compound meters have a beat that is a dotted note and the beat is equally divided into three. [5.1]

- The time signature for compound meters has two numbers, one above the other. [5.2]

- The top number means how many divisions per measure, so divide the top number by three to find how many beats there are per measure. The top number can be 6, 9, or 12.

- The bottom number means what type of note gets the division, so the beat is the next higher note value with a dot. The bottom number is usually 4, 8, or 16, but can technically be any note value (e.g., 2).

- We combine beat and meter classifications to describe time signatures (e.g., compound triple). [5.3]

- When identifying simple or compound meters: [5.4]

- Visually: dotted-note beats and divisions of three indicate compound meters

- Aurally: compound meters have a swinging feel

- Time signatures with the number “3” can be simple triple or compound single. [5.5]

- Rhythmic transposition is when you reinterpret a time signature in another time signature where the note value of the beat differs. [5.6]

- To double the value of a dotted note, use the next higher note value with a dot.

- To halve the value of a dotted note, use the next lower note value with a dot.

- A musical ornament is an added note or notes that decorates the main note. There are five main types: [5.7]

- Grace note (or acciaccatura)

- Appoggiatura

- Mordent

- Turn

- Trill

- In addition to the final double bar line, there are other types of endings: [5.8]

- Repeat signs

- D. C. al Coda

- D. C. al Fine

- D. S. al Coda

- D. S. al Fine

-

TERMS

-

-

- appoggiatura

- compound meters

- D. C. al Coda (da capo al coda)

- D. C. al Fine (da capo al fine)

- D. S. al Coda (dal segno al coda)

- D. S. al Coda (dal segno al fine)

- grace note (acciaccatura)

- mordent

- ornament

- repeat sign

- first ending/second ending

- trill

- turn

-

- Franz von Suppé (1819-1895) was an Austrian composer. ↵

- Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) was a Polish composer and pianist. ↵

- Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was a German composer. ↵

- Charles Gounod (1818-1893) was a French composer. ↵

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was an Austrian composer. ↵

- Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was a French composer. ↵

- Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896) was a German composer and pianist. ↵

- Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. ↵

- Maria Anna Martinez (1744-1812) was an Austrian composer. ↵

- Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) was a German composer. ↵

- Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836) was a French composer. ↵

- Josephine Lang (1815-1880) was a German composer. ↵

- Amanda Röntgen-Maier (1853-1894) was a Swedish composer and violinist. ↵

Meter in which the dotted note is the beat and divides equally into three.

A time signature in which the beat is a dotted note and equally divides into three (compound) and there are two beats per measure (duple).

A time signature in which the beat is a dotted note and equally divides into three (compound) and there are three beats per measure (triple).

A time signature in which the beat is a dotted note and equally divides into three (compound) and there are two beats per measure (quadruple).

A time signature in which the beat is a dotted note and equally divides into three (compound) and there is one beat per measure (single).

An added note or notes that decorates the main note. It can be represented by a small note or by a symbol. Also called an embellishment.

Small decorative note that is played quickly and right before the main note falls on the beat.

A musical ornaments that appears as a tiny note without a slash. It usually means its value is half of the following main note.

A musical ornament that tells the musician to play an upper neighboring note (e.g., C-D-C) or a lower neighboring note (e.g., C-B-C).

A musical ornament that tells the musician to decorate the main note by approaching it from a step above, return to the main note, move a step below, then return to the main note.

A musical ornament that tells the performer to repeat alternating notes. The trill can vary in duration and can even continue for multiple measures.

Symbols that tell you to repeat a section or the entire piece.

Go back to the beginning and perform until the double bar line. Also da capo al fine.

Go back to the symbol and perform until the double bar line. Also dal segno al fine.

Return to the beginning, but when you reach the coda symbol, jump to the other coda symbol. Also known as Da capo al coda.

Go back to the sign, but when you reach the coda symbol, jump to the other coda symbol. Also dal segno al coda.