4 Major Scales and Keys

Using the half steps and whole steps we learned about in Chapter 2, we will discover a new scale called the major scale. From the major scale, we will learn about major keys and their key signatures.

4.1 DIATONIC SCALE

In Chapter 2, we learned that a scale was a convenient way to organize notes alphabetically from one pitch to another pitch an octave away. The chromatic scale used all twelve keys on the keyboard by using a combination of chromatic and diatonic half steps.

- Recall that a half step is the smallest distance between two keys on the piano. Half steps can be chromatic (same note name, such as D and D

) or diatonic (different note name, such as D and E

) or diatonic (different note name, such as D and E ).

). - Two half steps create a whole step.

There are other scales in addition to the chromatic scale, but only the chromatic scale uses chromatic steps. All other scales are diatonic scales, which have several characteristics:

- Diatonic scales use only diatonic half steps and diatonic whole steps. In other words, diatonic scales do not contain any chromatic half steps or whole steps.

- Diatonic scales must use each letter name once and only once.

- Diatonic scales cannot skip a letter name.

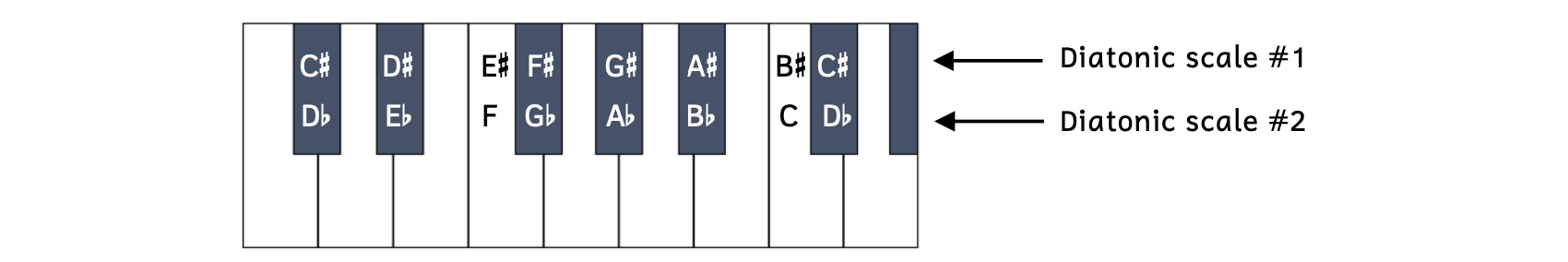

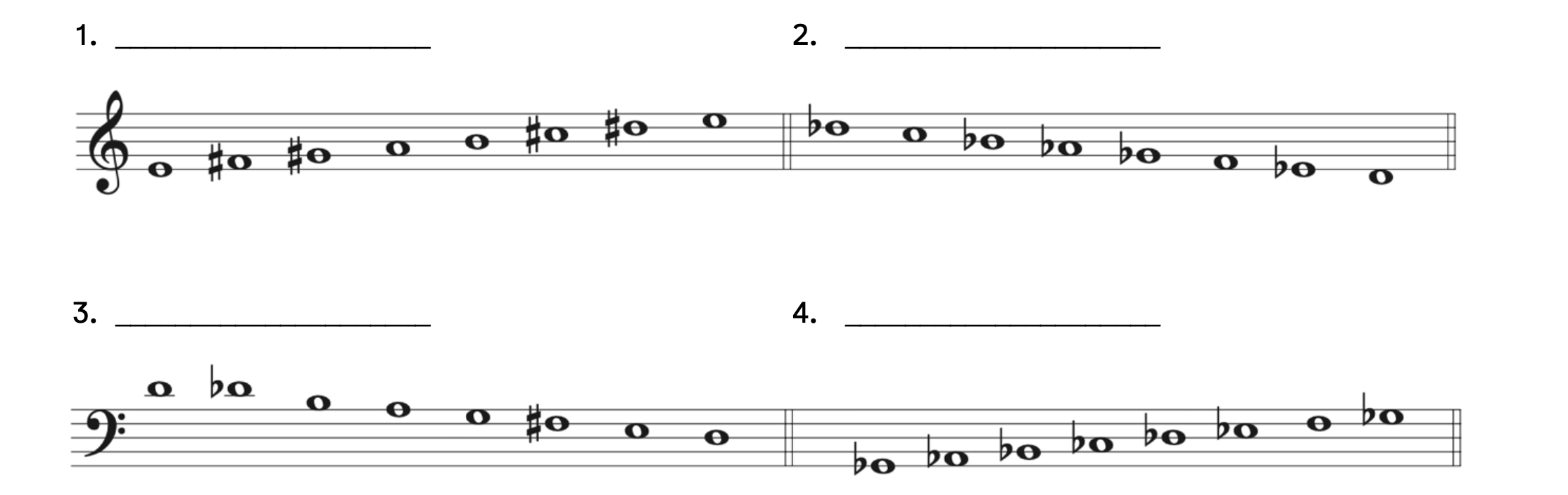

Observe the diatonic scales in Example 4.1.

Example 4.1. Diatonic scales

Notice how both diatonic scales above contain the same keys on the keyboard. However, because you must use every letter name once and only once, the scales use different sets of pitches.

- Look at the first two keys on the keyboard:

- If the first note is C

, the second note must be D-something, since we cannot use C again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the second note is D

, the second note must be D-something, since we cannot use C again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the second note is D .

. - If the first note is D

, the second note must be E-something, since we cannot use D again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the second note is E

, the second note must be E-something, since we cannot use D again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the second note is E .

. - While the second note in the first collection was D

, it is incorrect to call the second note D

, it is incorrect to call the second note D in the second collection; you must call it E

in the second collection; you must call it E .

.

- If the first note is C

- Look at the last two keys on the keyboard:

- If the last note is C

, the penultimate (second-to-last) note must be B-something, since we cannot use C again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the penultimate note is B

, the penultimate (second-to-last) note must be B-something, since we cannot use C again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the penultimate note is B .

.

- Although it seems like C would be much easier to read than B

, in the context of scales, it is easier to read the penultimate note as B

, in the context of scales, it is easier to read the penultimate note as B . It would be incorrect to write B

. It would be incorrect to write B as C, no matter how much you think it is better.

as C, no matter how much you think it is better.

- Although it seems like C would be much easier to read than B

- If the last note is D

, the penultimate note must be C-something, since we cannot use D again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the penultimate note is C.

, the penultimate note must be C-something, since we cannot use D again and we cannot skip a letter name. Therefore, the penultimate note is C.

- If the last note is C

Diatonic Scale

Unlike chromatic scales, which used all twelve keys on the keyboard, diatonic scales can only use each letter name once. As a result, diatonic scales only use diatonic steps and have seven different notes.

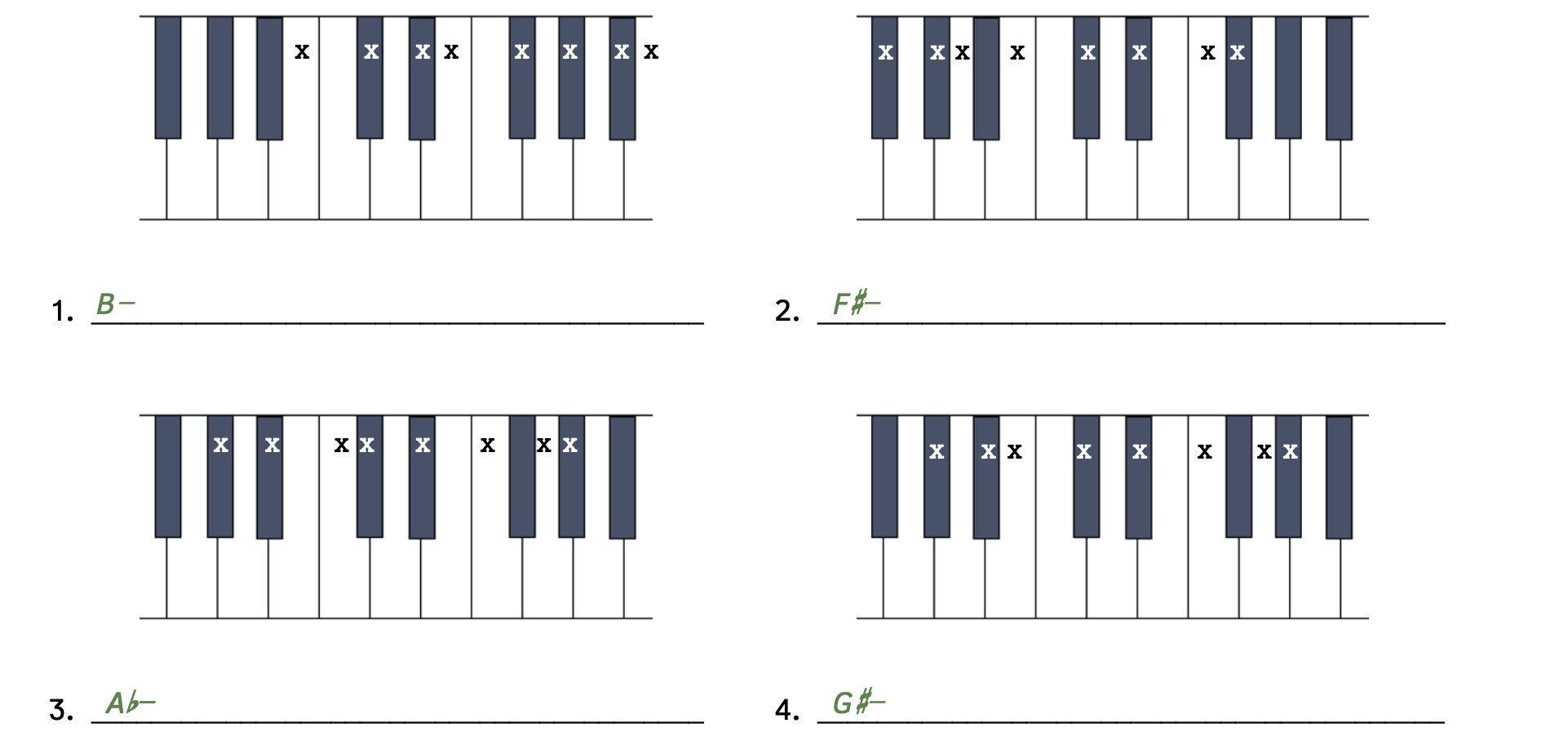

Practice 4.1. Writing Diatonic Scales

Directions:

- Write the diatonic scales indicated by the selected notes on the keyboard as note names in the spaces below. Be sure to use each letter name once and only once. See Example 4.1 for a sample.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) F

3) A

4) G

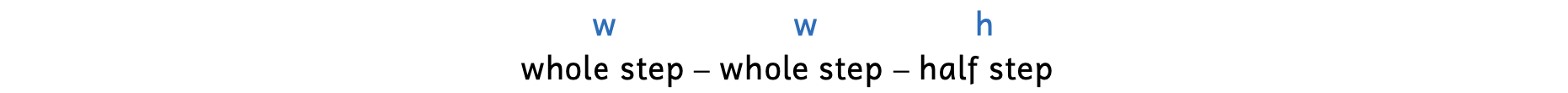

4.2 TETRACHORDS

“Tetra” comes from the Greek meaning “four” and tetrachords refer to a collection of four notes that are melodic, meaning that each note is played one at a time. The major tetrachord consists of the following pattern: whole step (w) – whole step (w) – half step (h).

In order to create major tetrachords, write notes diatonically (i.e., write each letter name once and only once) while adding the appropriate accidentals.

Note that each letter name is only used once and letter names cannot be skipped. For example, the second note in the major tetrachord from F![]() must be G

must be G![]() and not A

and not A![]() .

.

If you have been to a baseball game, you may have heard the major tetrachord performed by the organist, as everyone cheers, “charge!”

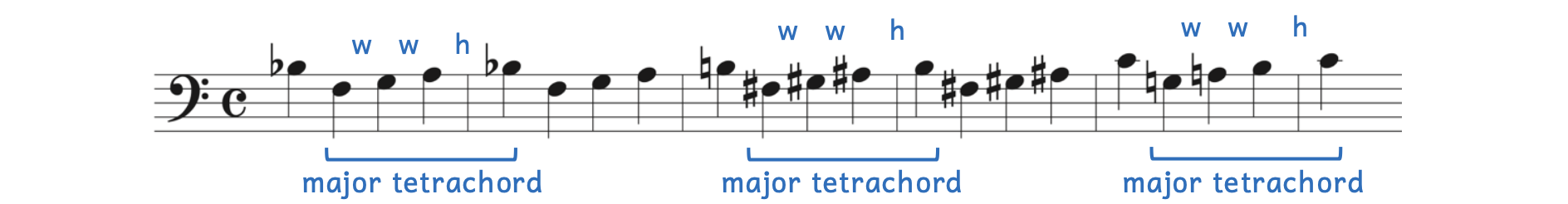

Example 4.2.1. Major tetrachord: Baseball Cheer

In Example 4.2.1, there are three major tetrachords. Each labeled major tetrachord is a half step higher than the previous.

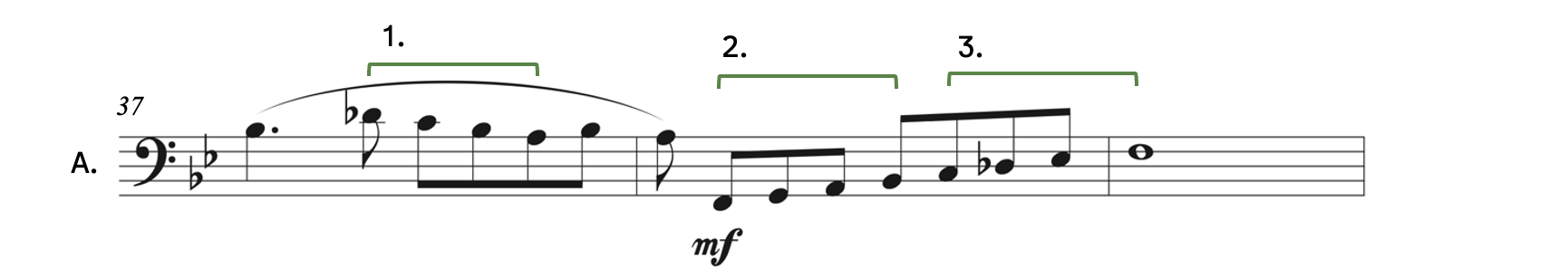

The major tetrachord is not uncommon in music. Krumpholtz uses the major tetrachord four times in Example 4.2.2.

Example 4.2.2. Major tetrachord: Krumpholtz[1], “The Favorite Air of Robin Adair”

Although Krumpholtz uses the major tetrachord G-A-B-C four times in Example 4.2.2, the major tetrachord is not as obvious as the baseball cheer in Example 4.2.1 because Krumpholtz varies each occurrence.

- In the first system, notes immediately preceding (measures 1-2) or following (measures 3-4) decorate the major tetrachord.

- In the second system, the major tetrachord appears in two different octaves.

Major Tetrachord

The major tetrachord consists of four notes using the following diatonic steps: whole step – whole step – half step.

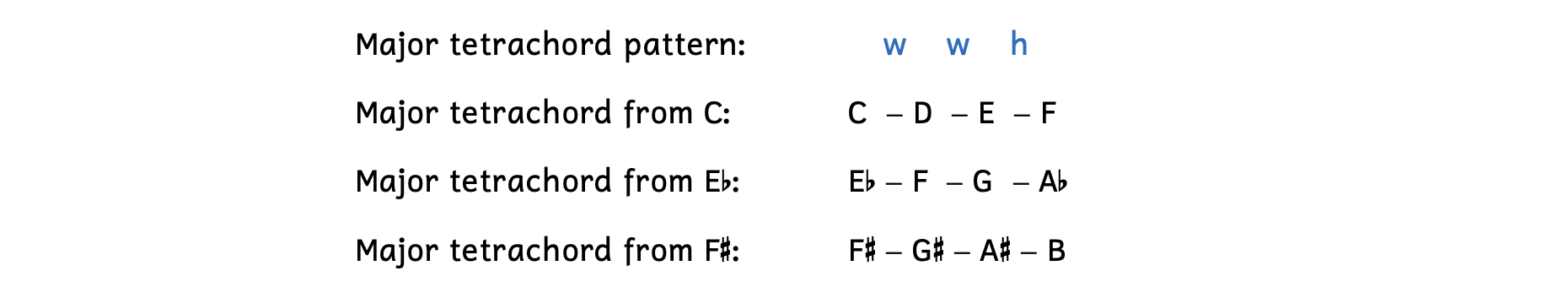

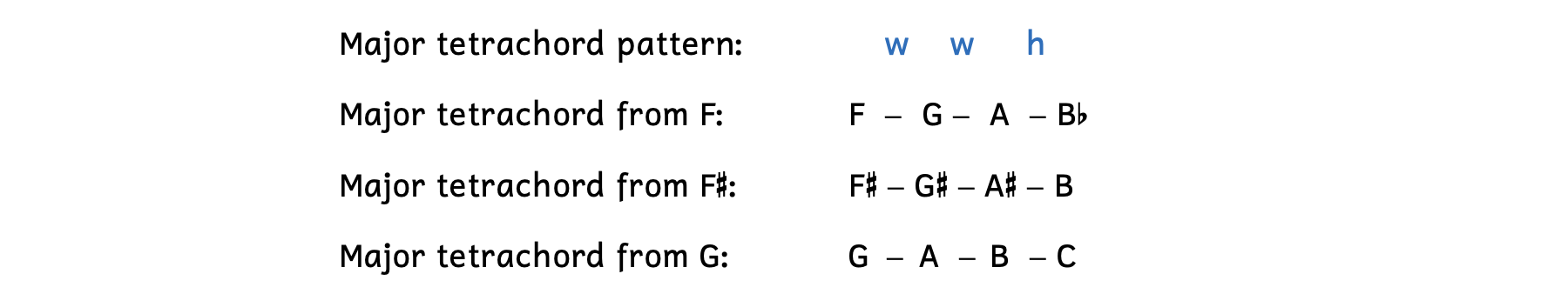

Practice 4.2A. Writing Major Tetrachords

Directions:

- Based on the given first note, fill in the blanks to complete major tetrachords.

- Write “w” to indicate whole steps and “h” to indicate half steps.

- You may use the keyboard below for help.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) E – F

3) G

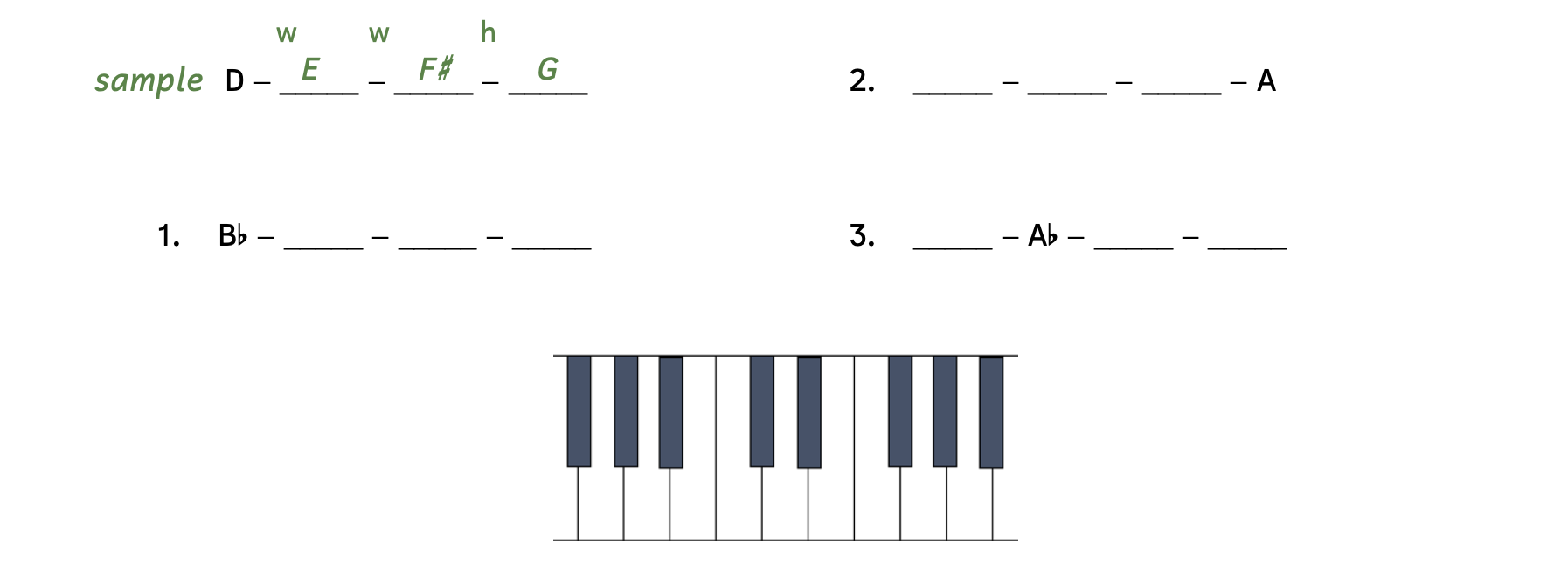

Practice 4.2B. Identifying Major Tetrachords

Directions:

- Identify the given tetrachords as either “major” or “X” if it is not a major tetrachord.

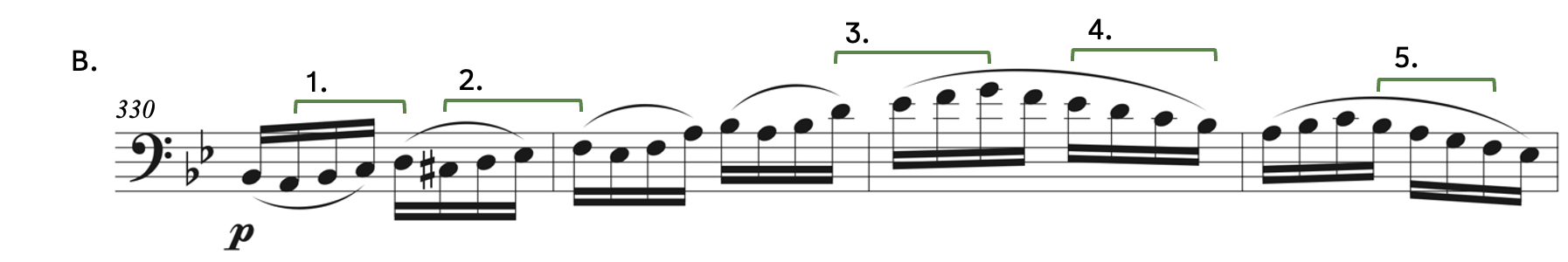

Farrenc[2], Cello Sonata, Op. 46, i – Allegro moderato

Farrenc, Cello Sonata, Op. 46, iii – Finale. Allegro

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

A2) major

A3) X

B1) X

B2) X

B3) X

B4) major

B5) major

4.3 MAJOR SCALES

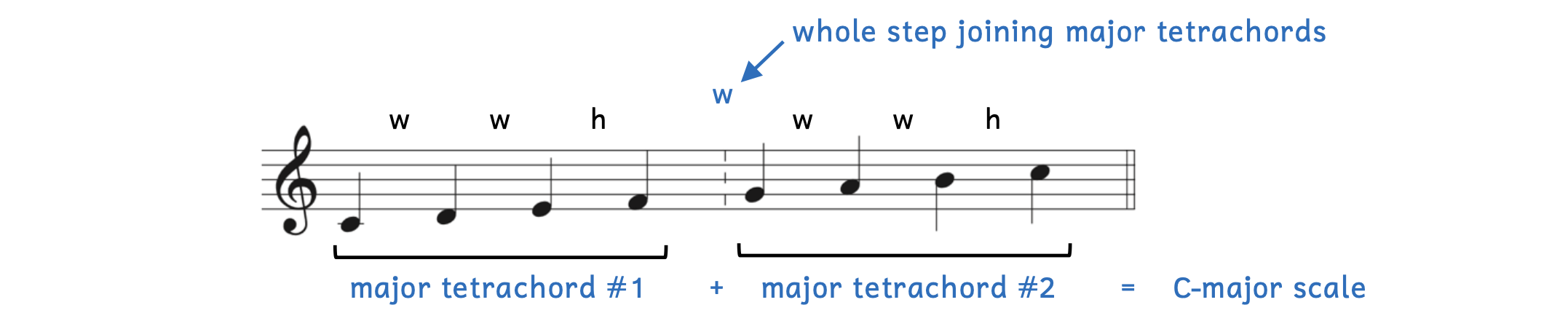

When we take a major tetrachord and write another major tetrachord joined by a whole step, what results is a major scale.

Example 4.3.1. Major scale

- Major tetrachord #1 consists of C-D-E-F (whole-whole-half).

- Major tetrachord #2 consists of G-A-B-C (whole-whole-half).

- When the two tetrachords are joined by a whole step, what results is a major scale.

- The example above is called a C major scale because C is the first and last note of the scale.

Although the major scale itself is not a very tuneful melody, we often find the major scale to create emphasis, give rise to tension, or add filler as in Examples 4.3.2 and 4.3.3.

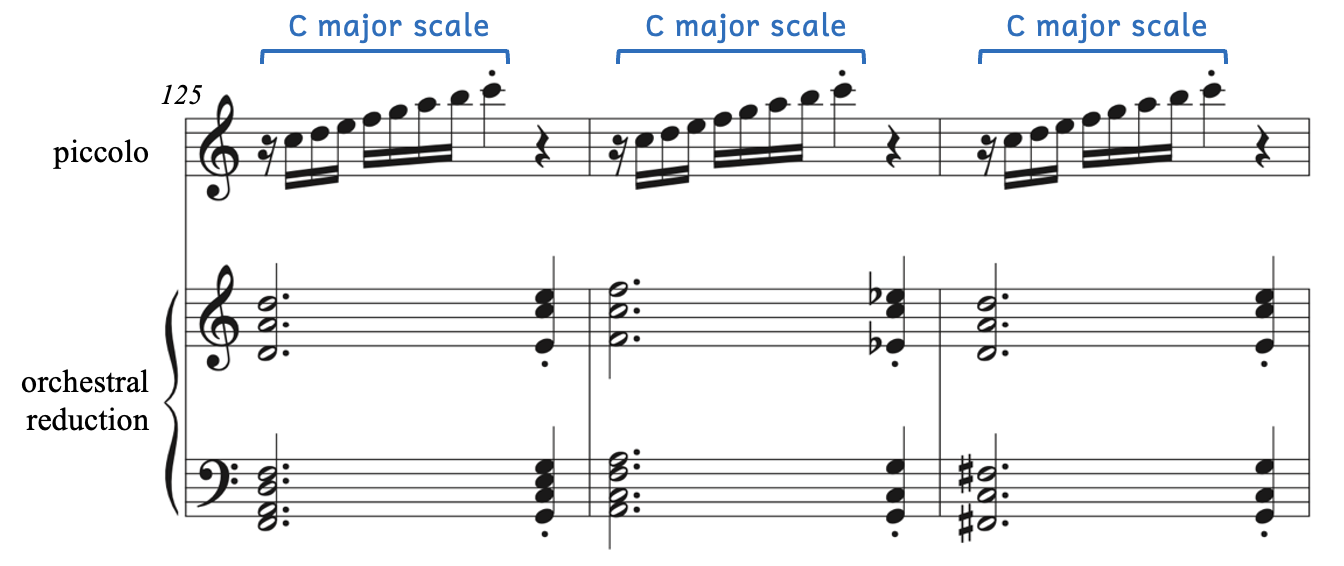

Example 4.3.2. Major scale: Beethoven[3], Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67, iv – Allegro

The orchestra has the main melody in Example 4.3.2. However, the piccolo’s repeated ascending C major scale adds to the excitement. The descending major scale can be used the same way.

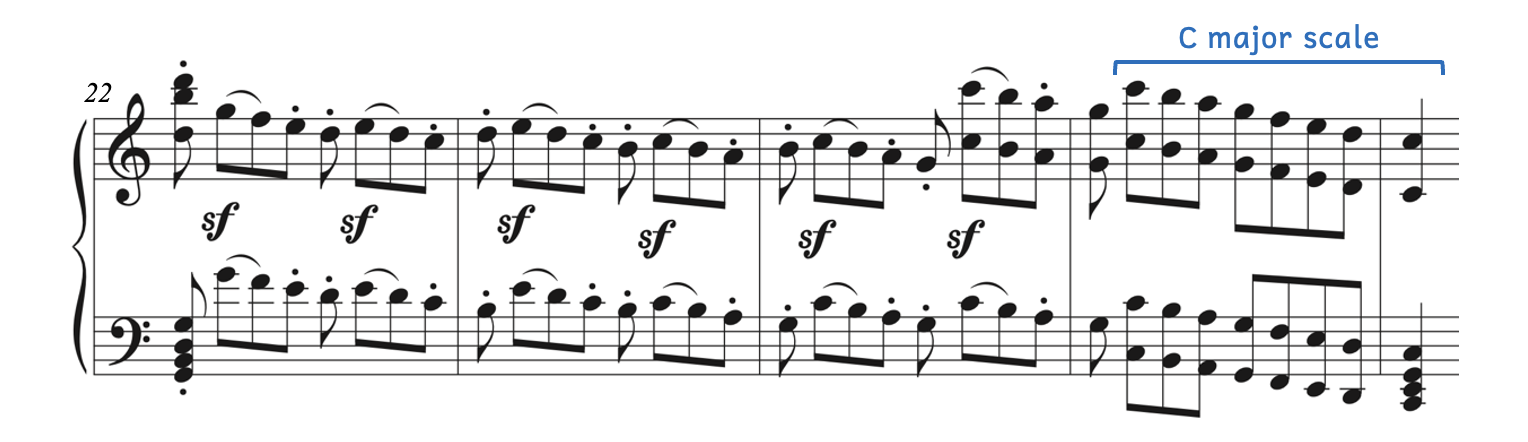

Example 4.3.3. Descending major scale: Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67, iv – Allegro

Listen to Example 4.3.3 and how the energy builds and climaxes at the end of the descending C major scale.

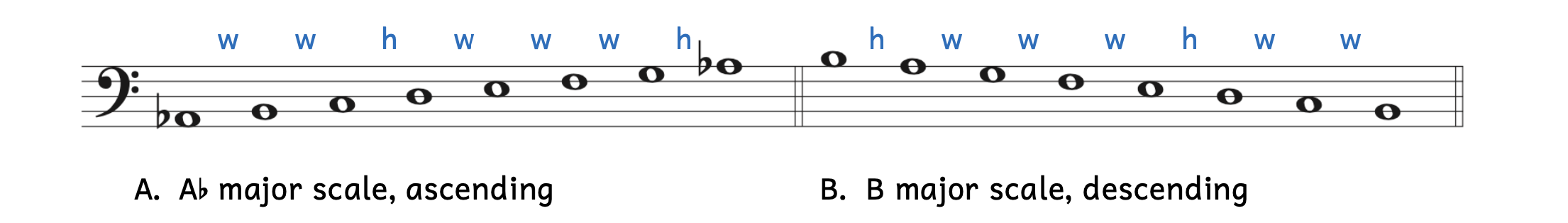

For major scales, you can either think of two major tetrachords separated by a diatonic whole step, or you can think of the entire pattern of diatonic half steps and diatonic whole steps:

- Option 1: Two major tetrachords separated by a whole step:

- whole – whole – half :: whole :: whole – whole – half

- Option 2: The entire major scale pattern:

- whole – whole – half – whole – whole – whole – half

As musicians, you will be asked to write, identify, and perform ascending and descending major scales. For descending scales, be sure to use the pattern in reverse order.

Steps to Writing a Major Scale

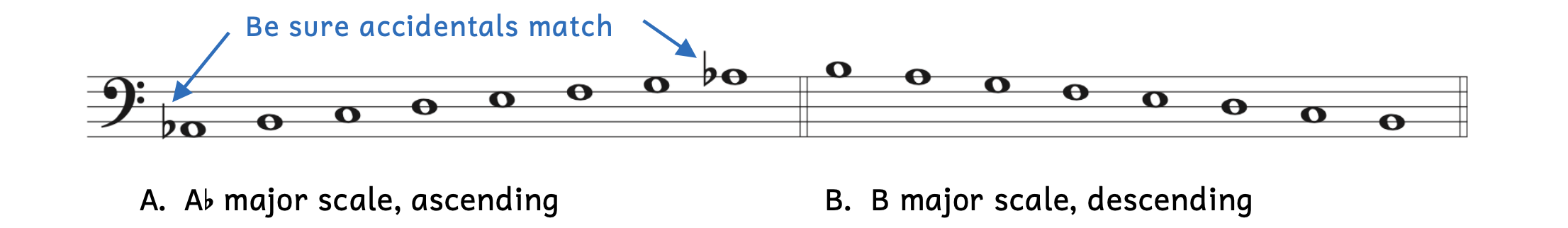

Step one: Write in all the notes diatonically: write each note once and only once in ascending or descending order (alternate line–space or space–line). Do not skip any notes and be sure that the first and last notes are the same notes with the same accidentals.

Example 4.3.4. Step one

Step two: Write in the pattern of whole steps and half steps. Do not forget that for descending major scales, the pattern must go in reverse.

Example 4.3.5. Step two

Step three: Add accidentals. Major scales will only contain sharps or flats—never both.

Example 4.3.6. Step three

Writing Major Scales

- Write in all the note names diatonically (once and only once) in ascending or descending order.

- Write in the pattern of whole steps and half steps: whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half.

- Add accidentals. Major scales will only contain sharps or flats–never both.

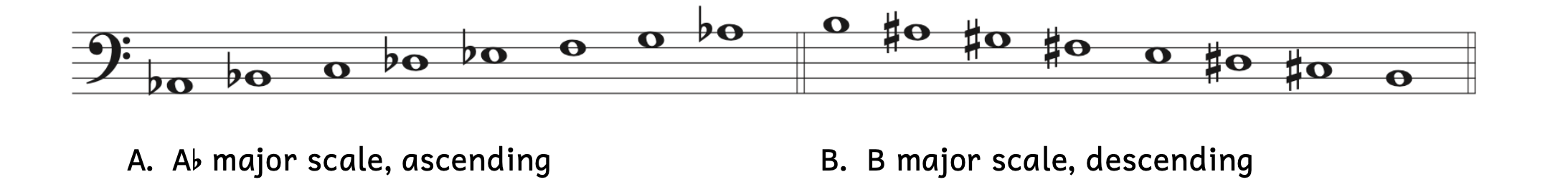

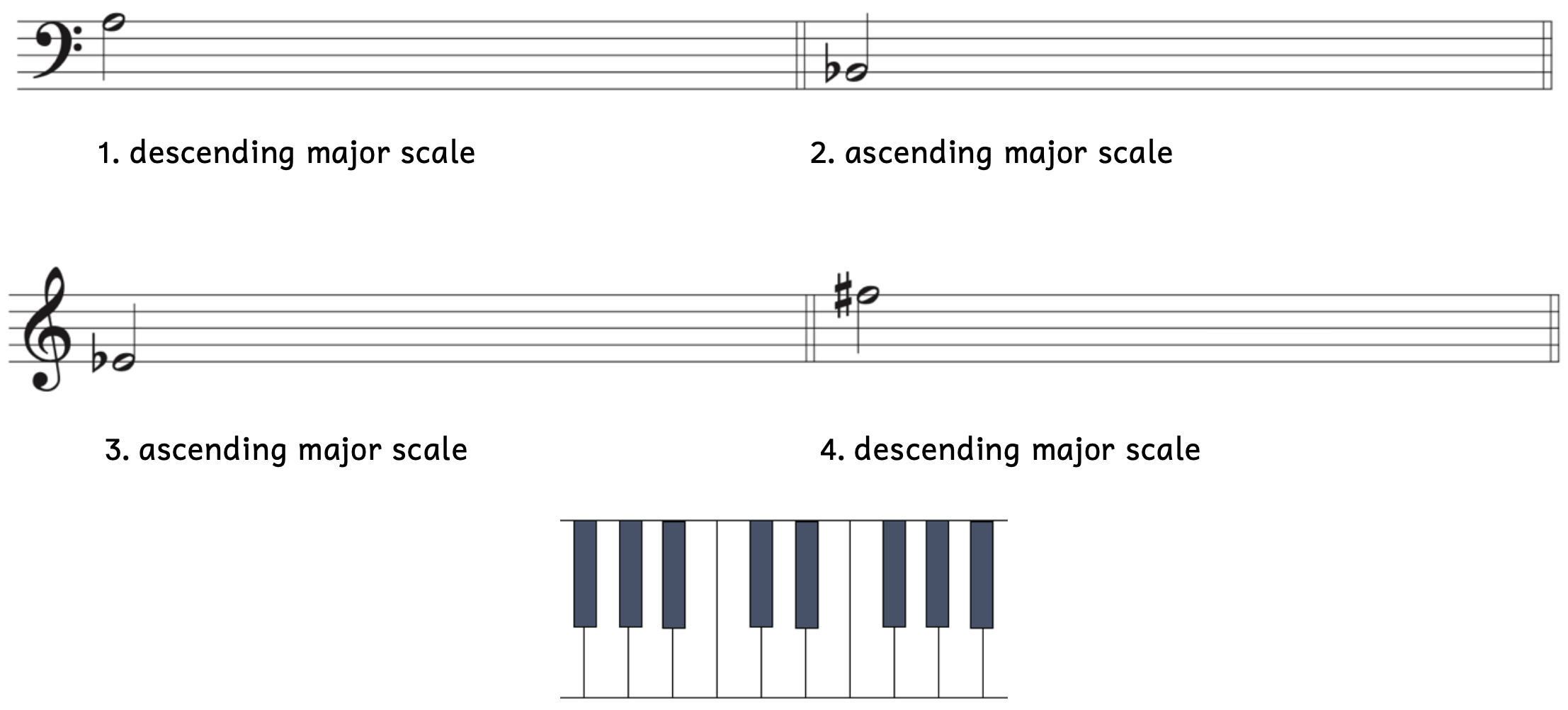

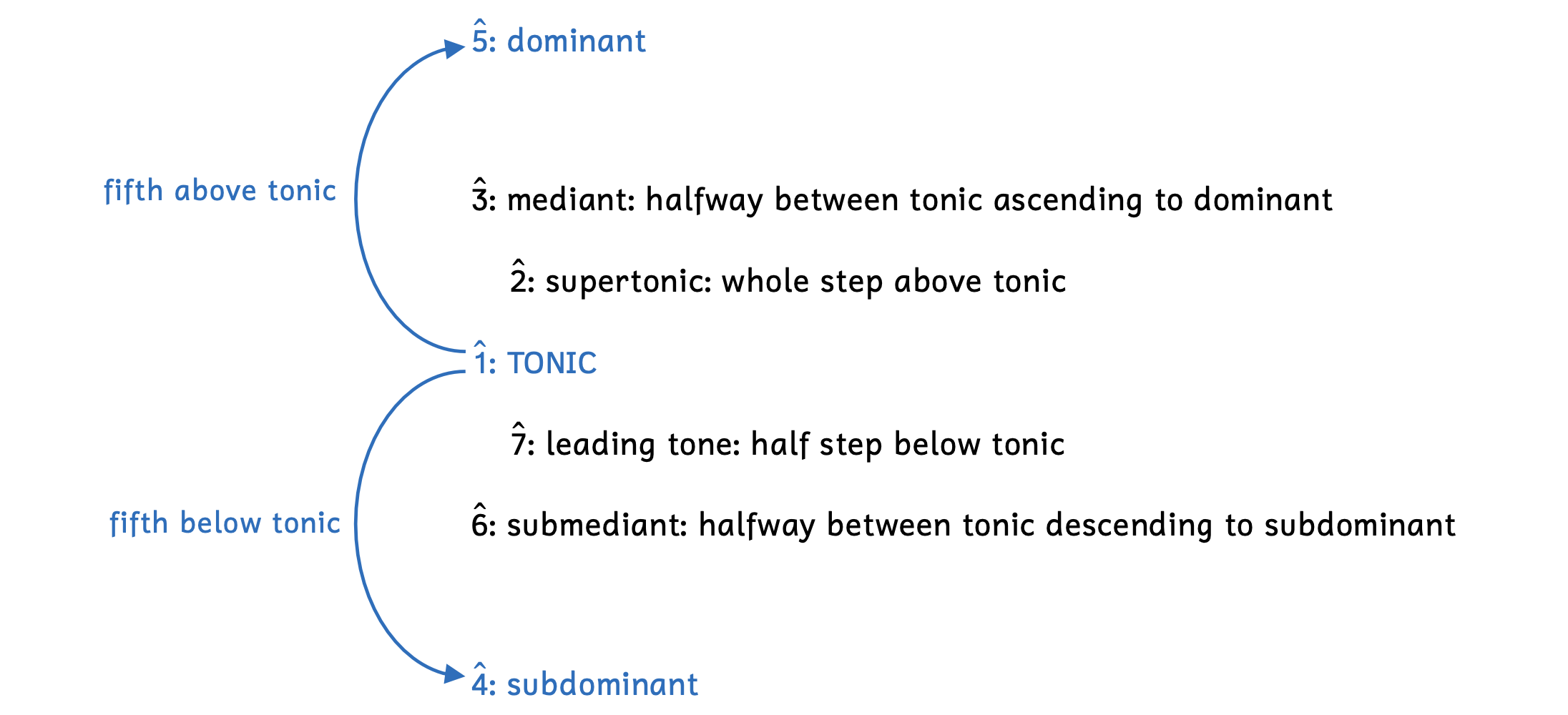

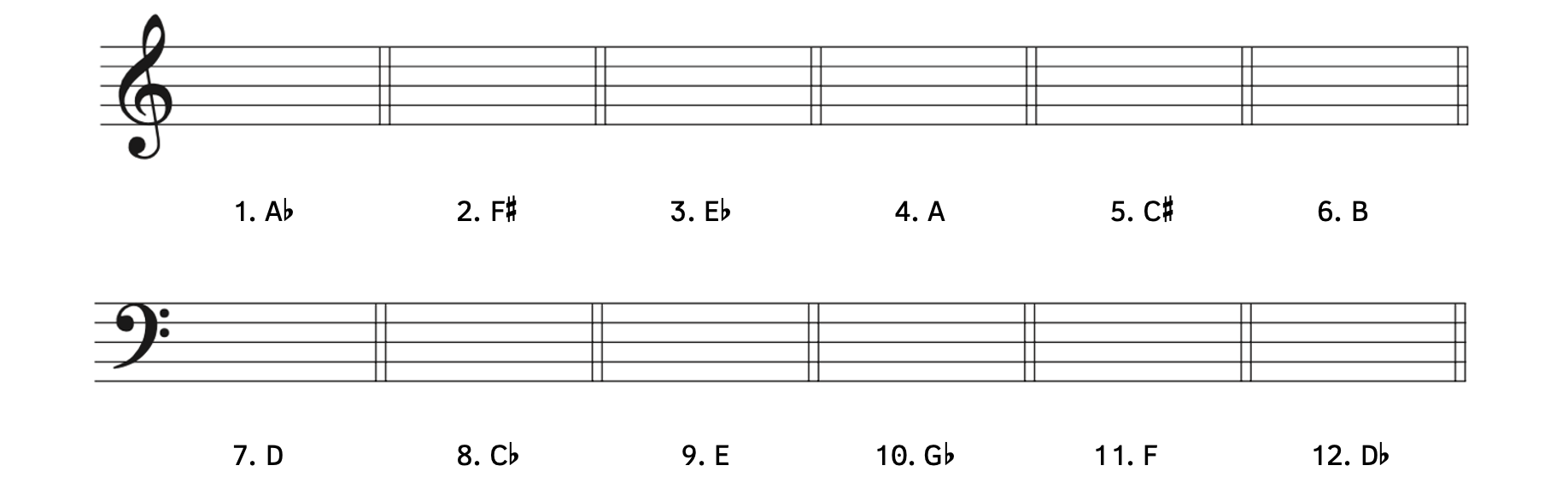

Practice 4.3A. Building Major Scales by Step Pattern

Directions:

- Construct the following major scales on the staff using half notes. Be aware of stem direction.

- First write in all the pitches diatonically so you do not repeat or skip any note names. Then add accidentals.

- If it helps, write in “w” for whole steps and “h” for half steps.

- You may use the keyboard below for help.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 4.3B. Identifying Major Scales

Directions:

- Identify the given scales as either “major” or “X” if it is not a major scale.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) X

3) X

4) major

4.4 SCALE DEGREES

Because the pattern of whole steps and half steps is the same for every major scale, every note is exactly the same distance apart between different major scales. For example, the third note in every major scale is exactly two whole steps away from the first note. To make this relationship clear, we use scale degree numbers and scale degree names.

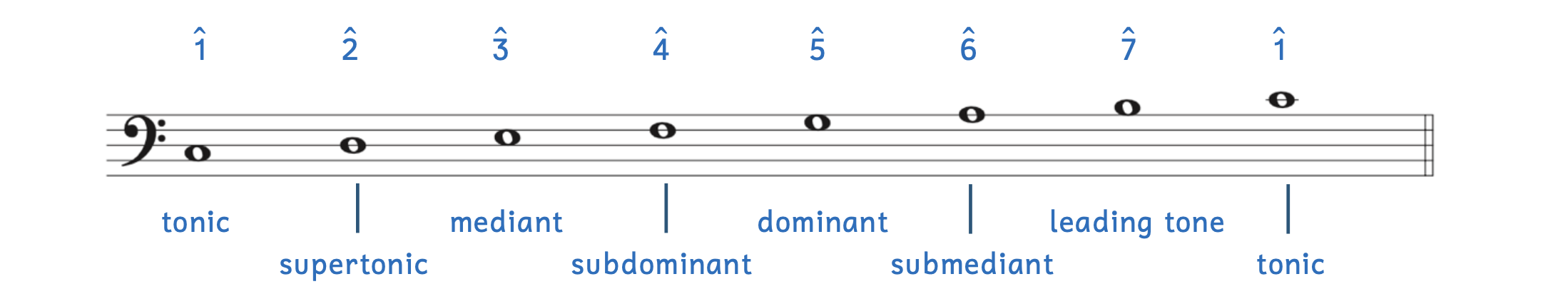

Example 4.4.1. Scale degrees in a C-major scale

Scale degree numbers tell us which member of the major scale a particular note is. Scale degree numbers are Arabic numerals with a caret (^) written above, as shown in Example 4.4.1. We say, “Scale degree three.”

- Notice that the last scale degree number is not

. Instead, it repeats

. Instead, it repeats  . This is because they are the same note name.

. This is because they are the same note name.

Scale degree names also tell us which member of the major scale a particular note is. Scale degree names and numbers are synonymous. The supertonic is always ![]() and vice versa.

and vice versa.

- The tonic (

) begins and ends the major scale.

) begins and ends the major scale. - The supertonic (

) gets its name because it is a whole step above the tonic (e.g., superscript is writing above the regular text).

) gets its name because it is a whole step above the tonic (e.g., superscript is writing above the regular text). - The mediant (

) is halfway between the tonic ascending to the dominant.

) is halfway between the tonic ascending to the dominant. - The subdominant (

) is a fifth below the tonic (e.g., subscript is writing below the regular text).

) is a fifth below the tonic (e.g., subscript is writing below the regular text). - The dominant (

) is a fifth above the tonic.

) is a fifth above the tonic. - The submediant (

) is halfway between the tonic descending to the subdominant.

) is halfway between the tonic descending to the subdominant. - The leading tone (

) gets its name because it is a diatonic half step below the tonic. It leads to the tonic. This book often abbreviates the leading tone as LT.

) gets its name because it is a diatonic half step below the tonic. It leads to the tonic. This book often abbreviates the leading tone as LT.

We are familiar with whole steps and half steps, but we have not yet learned about fifths. A fifth is the distance between a note and another note five note names away.

- For example, a fifth above C is G because there are five note names from C to G (C-D-E-F-G). The dominant is a fifth above the tonic, so the dominant of C is G.

- The subdominant is a fifth below the tonic. If we count five note names below C, we get F (C-B-A-G-F). Therefore, the subdominant of C is F.

A visualization of the scale degree names may be helpful.

Example 4.4.2. Scale degrees

Sometimes students struggle with remembering scale degree names. However, if you use a diagram such as Example 4.4.2, it may be easier to memorize scale degree names.

- The dominant is a fifth above the tonic.

- The mediant is halfway between the tonic ascending to the dominant.

- The subdominant is a fifth below the tonic.

- The submediant is halfway between the tonic descending to the subdominant.

- A step away from the tonic:

- The supertonic is a whole step above the tonic.

- The leading tone is a half step below the tonic.

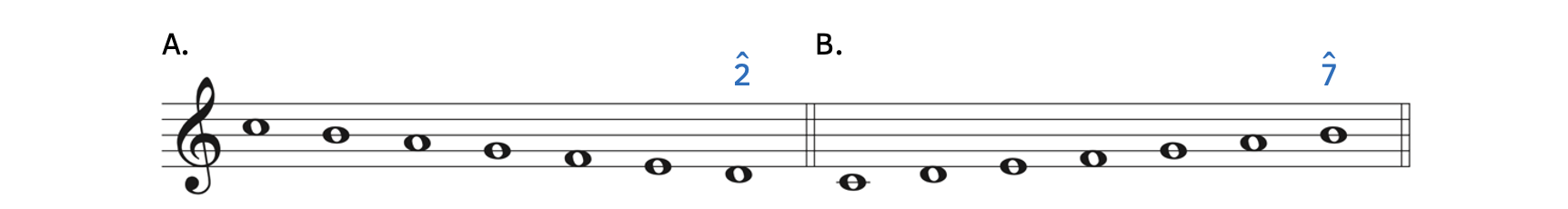

The last two bullet points describe scale degrees that are a step away from the tonic. Being only a step away from the tonic, the supertonic and leading tone have a strong pull to the tonic. As shown by the diagram in Example 4.4.2, the tonic is the focal point. Indeed, the C major scale is so named because its tonic is C. We can hear the musical pull to the tonic when we stop short before arriving to the tonic. Listen to Example 4.4.3—do you hear how strongly the music wants to reach the tonic?

Example 4.4.3. Pull to tonic: stopping short

- The descending C major scale stops short on the supertonic (

).

). - The ascending C major scale stops short on the leading tone (

).

).

The next two examples illustrate the pull to tonic.

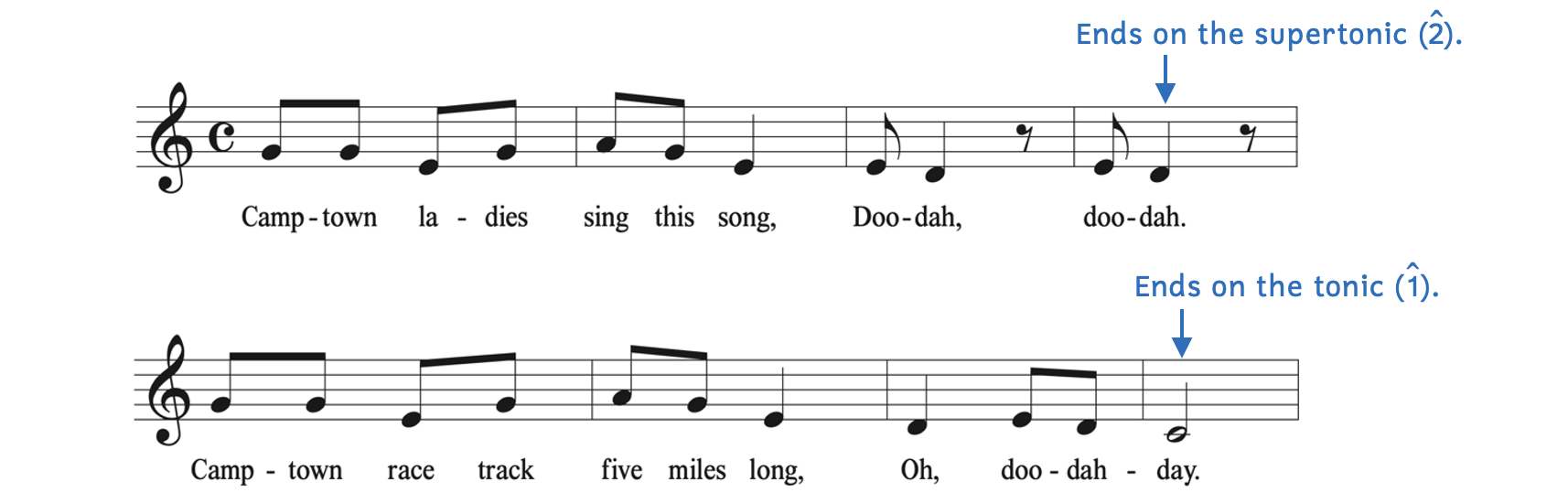

Example 4.4.4. Pull to tonic: Foster[4], “Camptown Races”

- The first system ends on the supertonic (

). The music does not sound conclusive, as we yearn for tonic.

). The music does not sound conclusive, as we yearn for tonic. - The second system ends on the tonic (

). The music finally sounds complete.

). The music finally sounds complete.

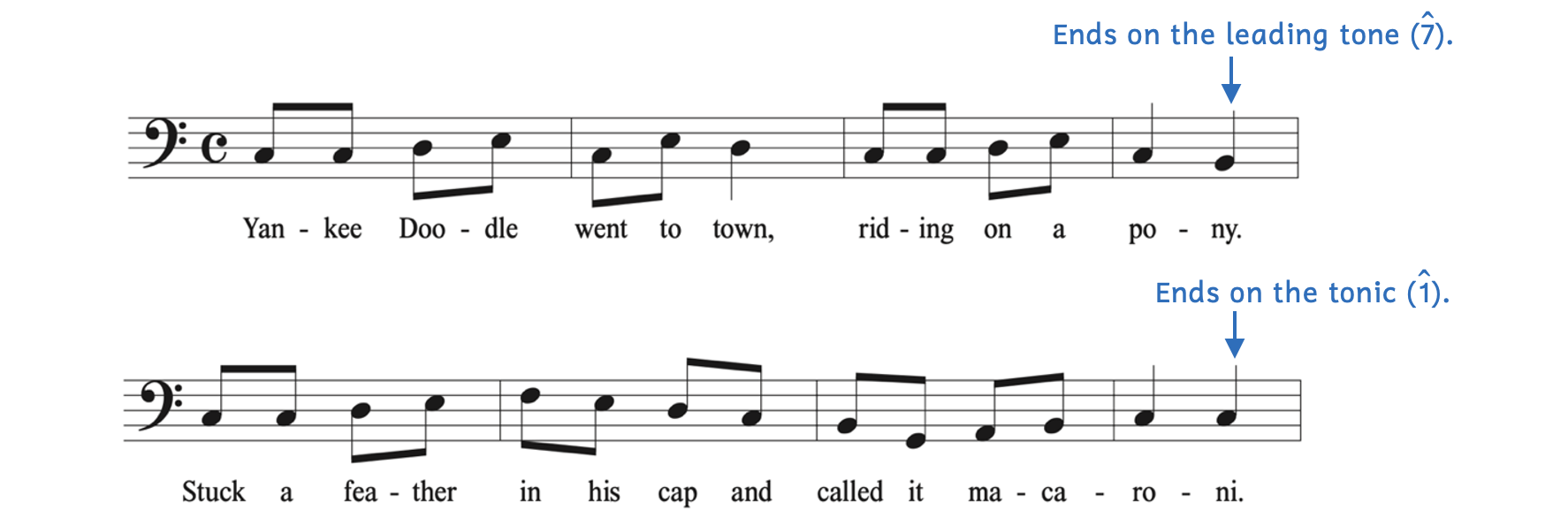

Example 4.4.5. Pull to tonic: “Yankee Doodle”

- The first system ends on the leading tone (

). The music does not sound conclusive, as we yearn for tonic.

). The music does not sound conclusive, as we yearn for tonic. - The second system ends on the tonic (

). The music finally sounds complete.

). The music finally sounds complete.

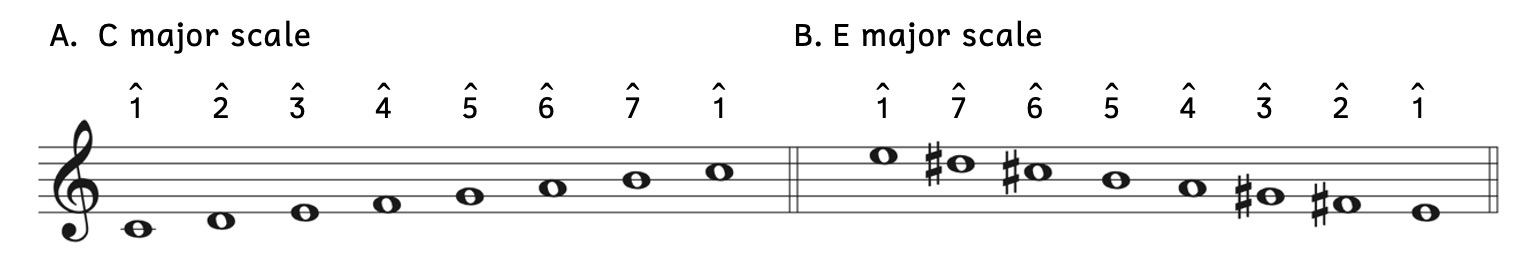

Compare the scale degrees in the next two major scales.

Example 4.4.6. Comparing scale degrees

- Scale degree numbers are based on the ascending scale, not the order in which they appear.

- The second note in Example 4.4.6B is

, and not

, and not  .

.

- The second note in Example 4.4.6B is

- The same note varies in scale degree depending on the scale.

- A is

in the C major scale (Example 4.4.6A), but is

in the C major scale (Example 4.4.6A), but is  in the E major scale (Example 4.4.6B).

in the E major scale (Example 4.4.6B).

- A is

In aural training, you may learn solfège (e.g., do–re–mi) to help you sing. Scale degrees are the same thing as solfège, but are used in music theory.[5]

Scale Degrees

Each member of a major scale has a scale degree number and scale degree name. The scale degrees help show the relationship between notes within the major scale, and the relationship between different major scales.

Practice 4.4. Scale Degrees in Major Scales

Directions:

- Answer the following questions based on the given major scale. First write in the scale degree numbers to help.

- Which note is the tonic?

- Which note is the dominant?

- Which note is

?

? - Which note is

?

? - What scale degree number is B?

- What scale degree number is E

?

? - Why is

called the subdominant?

called the subdominant? - Why is

called the leading tone?

called the leading tone? - Why is

called the mediant?

called the mediant? - Why is

called the supertonic?

called the supertonic?

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) C

3) D

4) G

5)

6)

7) fifth below tonic

8) leads to tonic

9) halfway between tonic ascending to dominant

10) whole step above tonic

4.5 MAJOR KEYS

A major scale is not only an organized way to write notes in alphabetical order. More importantly, the major scale is an organized way of telling us the contents of a musical key, which combines the tonal center and mode.

- The tonic is the tonal center. It is a note that tells us where “home” is; the music gravitates around the tonal center and does not feel complete unless we end at home. The tonal center can be any pitch, such as C, F

, or G

, or G .

. - The mode tells us the collection of pitches used based on a tonal center. The most common modes are the major mode and minor mode. Since the major mode and minor mode contain different notes, they sound different. The major mode is often associated with happy music, while the minor mode is often associated with sad music.

- The key combines the tonal center and mode (e.g., F

major or F

major or F minor). As you will learn later in this chapter, not every tonal center can have keys in both major and minor (e.g., you can have the key of G

minor). As you will learn later in this chapter, not every tonal center can have keys in both major and minor (e.g., you can have the key of G major but not G

major but not G minor).

minor).

Ideally, you will be able to hear a musical example and tell if it is in major or minor. Examples 4.5.1. and 4.5.2 are two famous classical works that are in major keys.

Example 4.5.1. Major key: Mozart[6], Eine kleine Nachtmusik, K. 525, i – Allegro

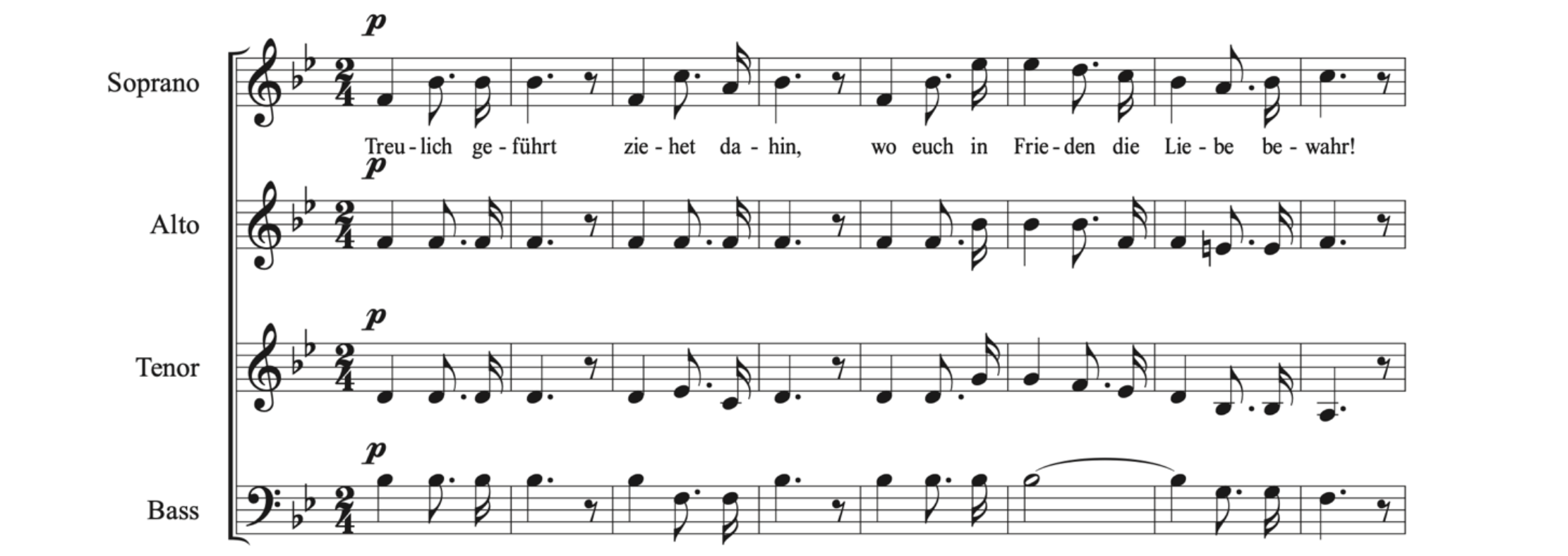

Example 4.5.2. Major key: Wagner[7], Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin, Act III, Scene i – Mässig bewegt[8]

Can you hear that the music in Examples 4.5.1 and 4.5.2 are in major (i.e., are “happy”)? If you are not able to do so yet, do not fret. Understanding, writing, and hearing music all take time and practice. We will even learn how you can recognize if a piece is in major without having to listen to it.

We can figure out a major key by its major scale.

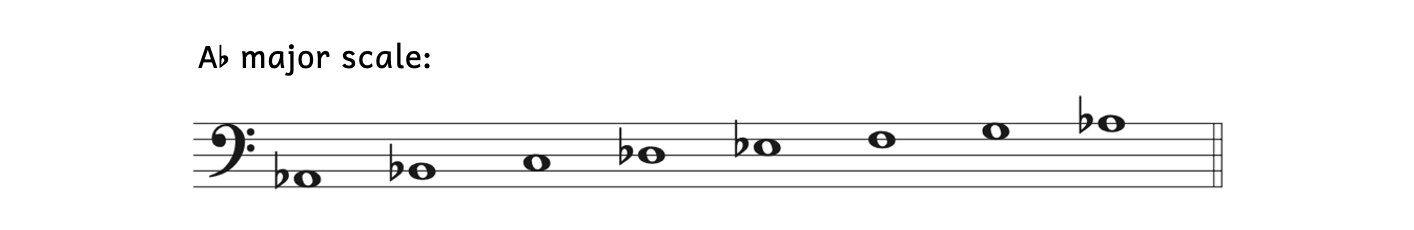

Example 4.5.3. From scale to key

The pitch collection combined with the tonal center tells us the key.

- If we have a piece of music that centers around A

with four flats, it is in the key of A

with four flats, it is in the key of A major.

major.

- The tonal center is A

because A

because A is the tonic.

is the tonic. - The mode is major because the notes create an A

major scale.

major scale. - Together, they make up the key of A

major.

major.

- The tonal center is A

- Although five flats appear in the A

major scale, there are only four different flats (A

major scale, there are only four different flats (A , B

, B , D

, D , E

, E ) since the first and last flat apply to A

) since the first and last flat apply to A s.

s. - This means that if a piece is in the key of A

major, every time you see A, B, D, or E, they will be A

major, every time you see A, B, D, or E, they will be A , B

, B , D

, D , or E

, or E .

.

Look at the example below, which shows the end of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” in the key of A![]() major.

major.

Example 4.5.4. “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” with accidentals

- When we last saw “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” it was in the key of C major (Example 3.9.5). There were no sharps or flats.

- In Example 4.5.4, the tonal center is A

because it ends on A

because it ends on A . Although ending on the tonal center is not a requirement, it often occurs.

. Although ending on the tonal center is not a requirement, it often occurs.

- More importantly, listen to the example—do you hear how it sounds like the end when we reach the ending? This is because we have arrived at the tonal center.

- The four flats (A

, B

, B , D

, D , E

, E ) tell us that we are in the major mode. We know this because the A

) tell us that we are in the major mode. We know this because the A major scale has four flats.

major scale has four flats.

- All the flats found in the A

major scale appear in this example. However, this is not a requirement.

major scale appear in this example. However, this is not a requirement.

- All the flats found in the A

- Therefore, the tonal center of A

+ the major scale (four flats) = the key of A

+ the major scale (four flats) = the key of A major.

major.

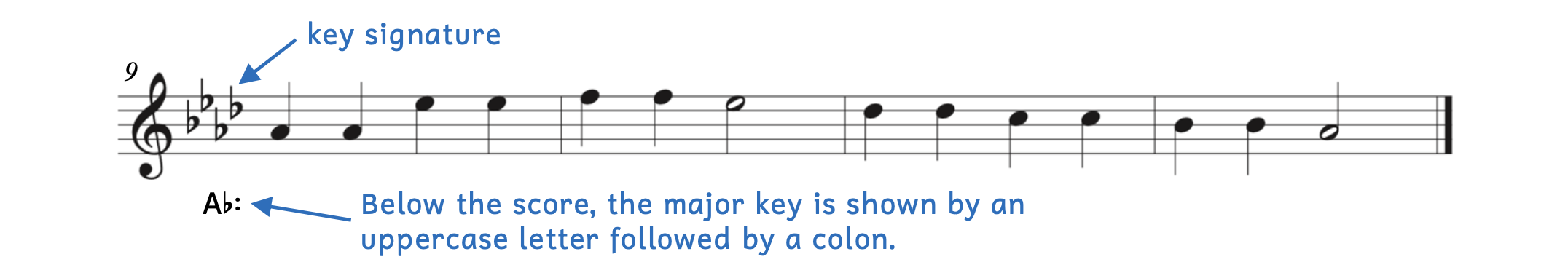

Rather than constantly writing and rewriting accidentals within the score, musicians use key signatures to simplify writing (and reading) music. A key signature is the group of flats or sharps located at the start of every system of music. The following example shows Examples 4.5.4 rewritten with a key signatures instead of accidentals. Example 4.5.5 sounds exactly the same as Example 4.5.4.

Example 4.5.5. “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” with a key signature

The key signature tells us which notes always have accidentals. For musicians, seeing the key signature once at the beginning is much easier than reading numerous accidentals.

When we wrote the A![]() major scale, it contained four flats. Therefore, the key signature of A

major scale, it contained four flats. Therefore, the key signature of A![]() major has four flats: Every B, E, A, and D will be B

major has four flats: Every B, E, A, and D will be B![]() , E

, E![]() , A

, A![]() , and D

, and D![]() unless there is a different accidental.

unless there is a different accidental.

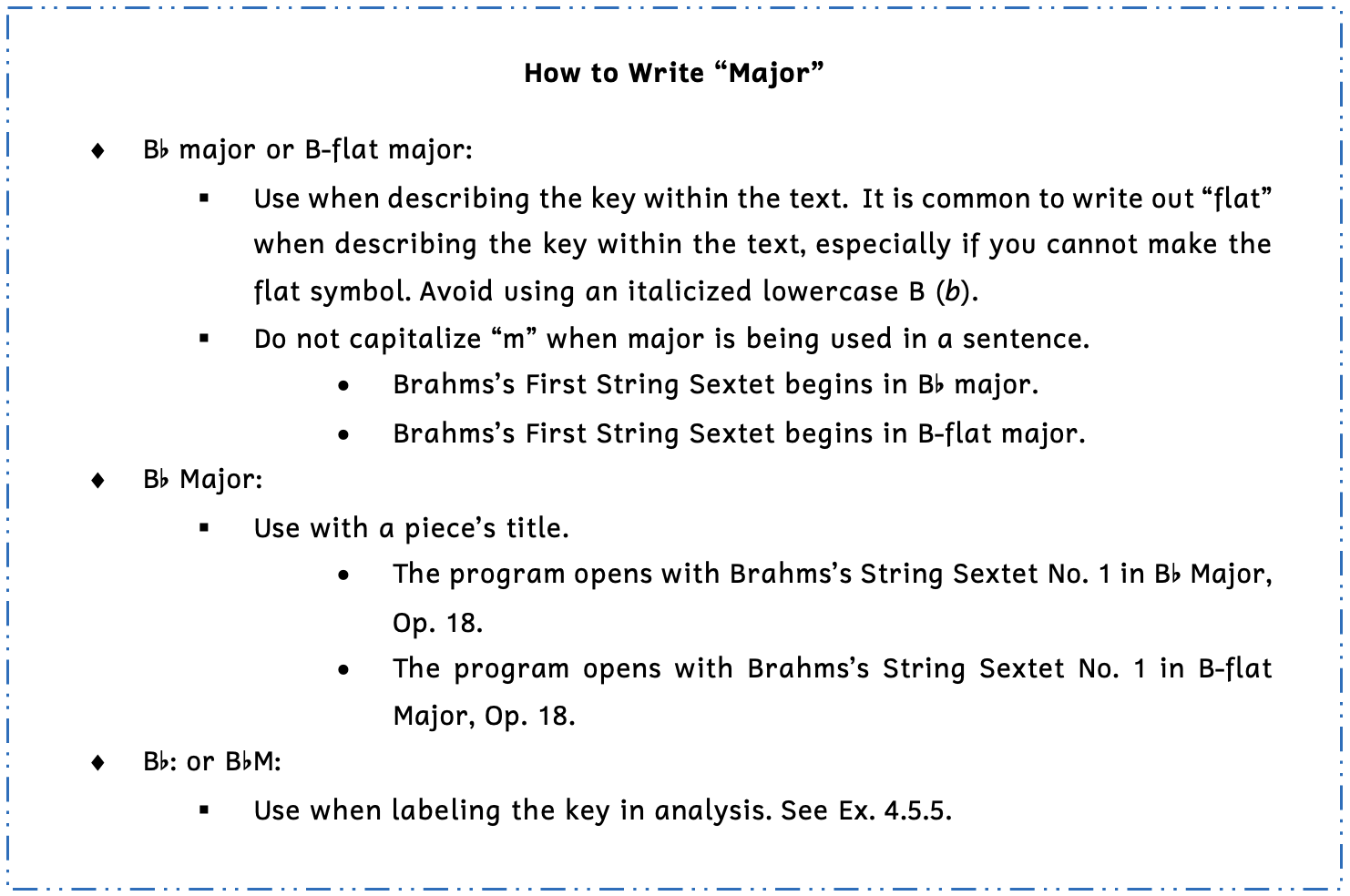

To label the major key, write an upper-case letter of the tonic (e.g., A![]() ) followed by a colon. Alternatively, you can also write an upper-case M after the tonic (e.g., A

) followed by a colon. Alternatively, you can also write an upper-case M after the tonic (e.g., A![]() M).

M).

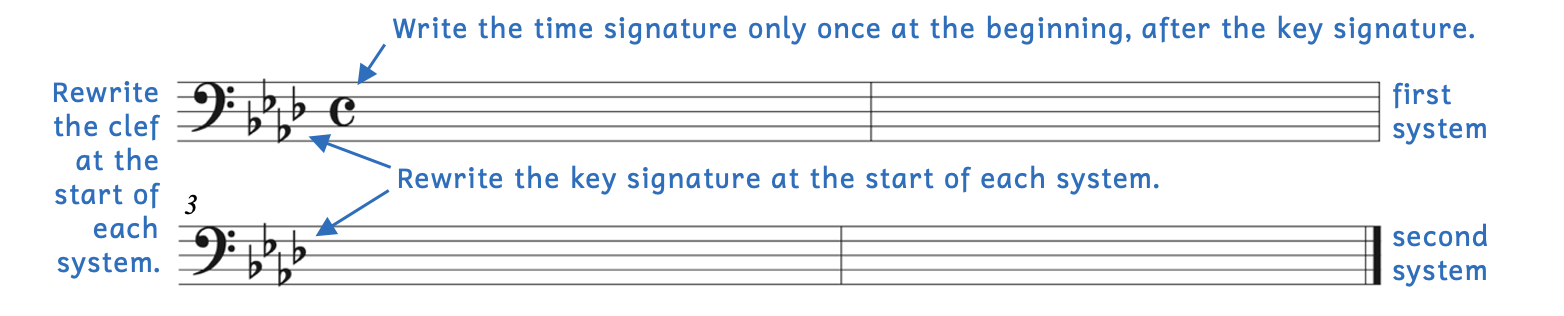

Unlike time signatures, key signatures are rewritten at the start of each system.

Example 4.5.6. Key signature versus time signature

- Each system must begin with a clef.

- The key signature appears immediately after the clef and each system must have the key signature (if there is one).

- The time signature only appears at the start of the composition or when the time signature changes. Do not rewrite the time signature at the start of each system.

- The order of appearance is clef, key signature, time signature. It may help you to memorize the order by remembering that the names are in alphabetical order (C – K – T).

Unlike accidentals, which were localized, key signatures are globalized. This means that with a key signature of A![]() major, all Bs are B

major, all Bs are B![]() .

.

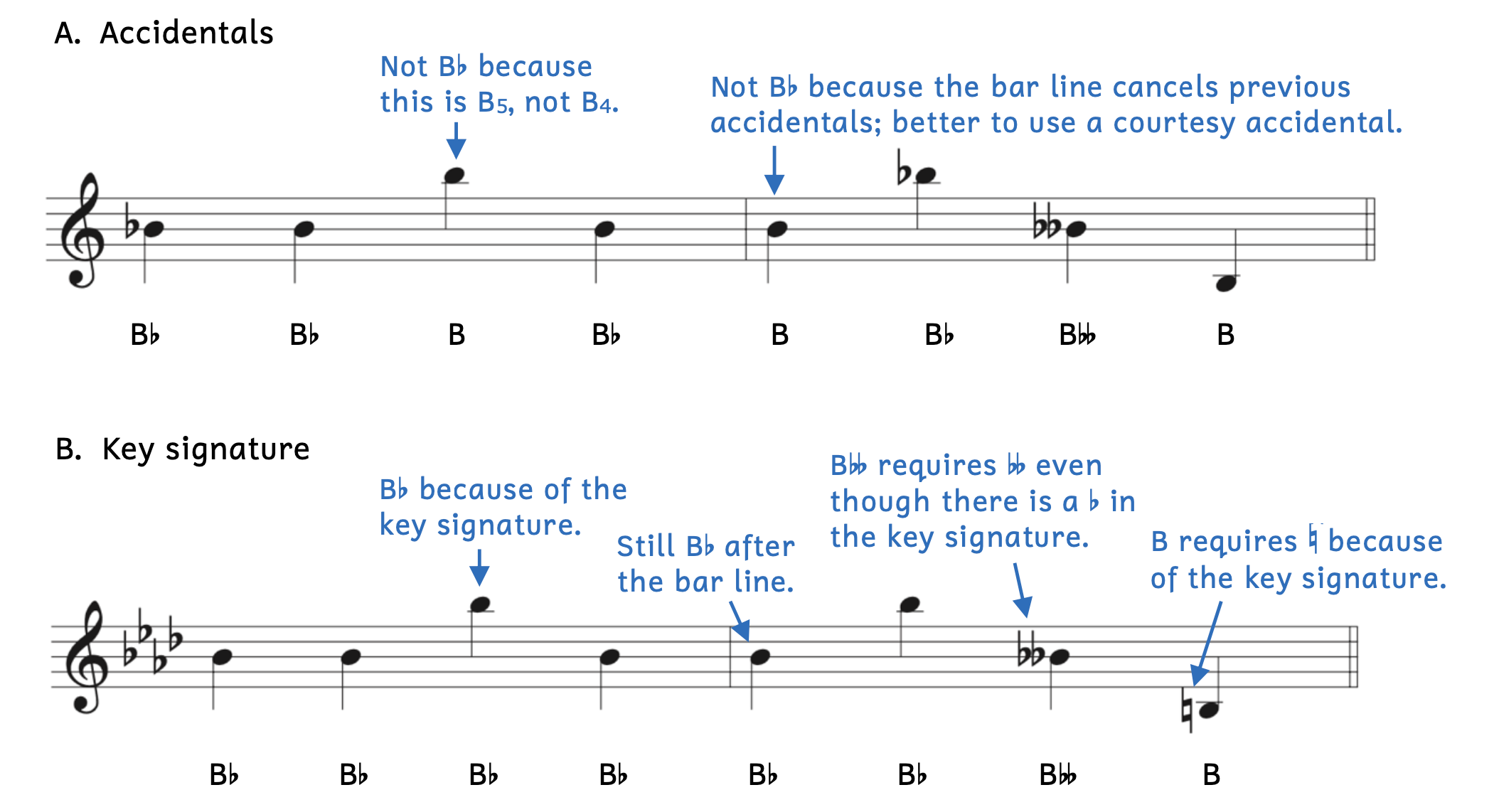

Example 4.5.7. Accidentals versus key signatures

Notice some important differences between accidentals versus key signatures.

- Accidentals (Example 4.5.7A):

- The third note is B (not B

) because the flat on the previous note only applied to B

) because the flat on the previous note only applied to B 4.

4. - The note after the bar line is B (not B

) because even though it is B

) because even though it is B 4, the bar line cancels previous accidentals.

4, the bar line cancels previous accidentals.

- The third note is B (not B

- Key signatures (Example 4.5.7B):

- The third note is B

because the key signature says all Bs are B

because the key signature says all Bs are B s.

s. - The note after the bar line is B

because bar lines make no difference: the key signature says all Bs are B

because bar lines make no difference: the key signature says all Bs are B s.

s. - The penultimate note requires a double flat when the desired note is B

. Sometimes students think adding a flat lowers B

. Sometimes students think adding a flat lowers B to B

to B ; however, adding a flat would only make the note B

; however, adding a flat would only make the note B .

. - The last note requires a natural sign if the desired note is B.

- The third note is B

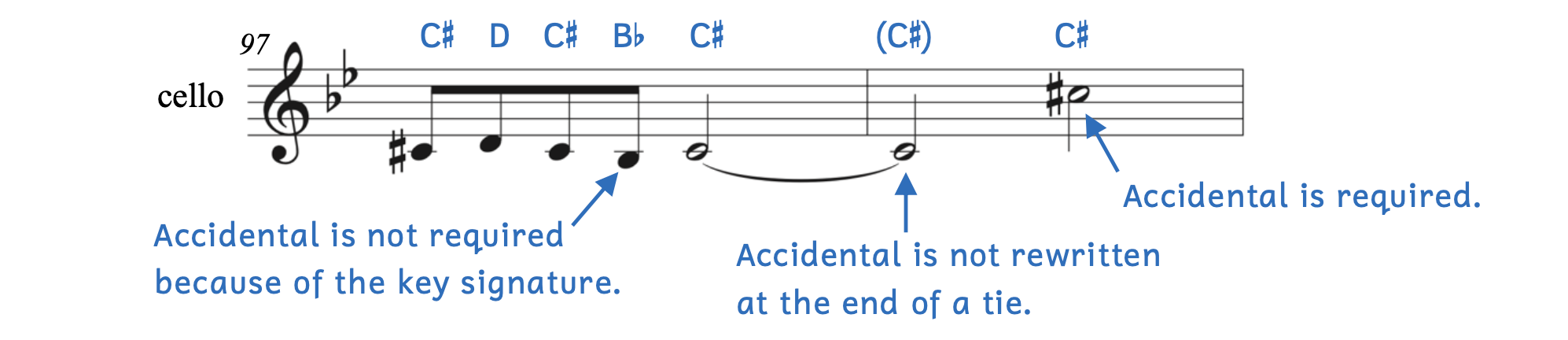

Example 4.5.8 illustrates how accidentals work within a key signature, as well as how they work with ties. The pitches are shown above the cello’s part.

Example 4.5.8. Accidentals and key signature: Bosmans[9], Impressions for Cello and Piano, I. Cortège

- The key signature shows that there are two flats in this key: every B and E are automatically flatted.

- There is a sharp on the downbeat of measure 97, resulting in a C

. The other two Cs are also C

. The other two Cs are also C because the accidental continues within the bar.

because the accidental continues within the bar. - The B

in measure 97 does not have an accidental because B

in measure 97 does not have an accidental because B is in the key signature.

is in the key signature. - The C

across the bar line is tied, making the note on the downbeat of m. 98 also C

across the bar line is tied, making the note on the downbeat of m. 98 also C . An accidental is unnecessary because of the tie.

. An accidental is unnecessary because of the tie. - On the second half of measure 98, C

returns and requires an accidental for several reasons.

returns and requires an accidental for several reasons.

- The previous bar line canceled the previous natural sign.

- The C is in another octave (C5 instead of C4).

Accidentals Versus Key Signatures

- Accidentals are localized, meaning that they only apply to a specific octave designation and do not last past the bar line.

- Key signatures are global, meaning notes have the accidental in any octave designation and despite any bar lines.

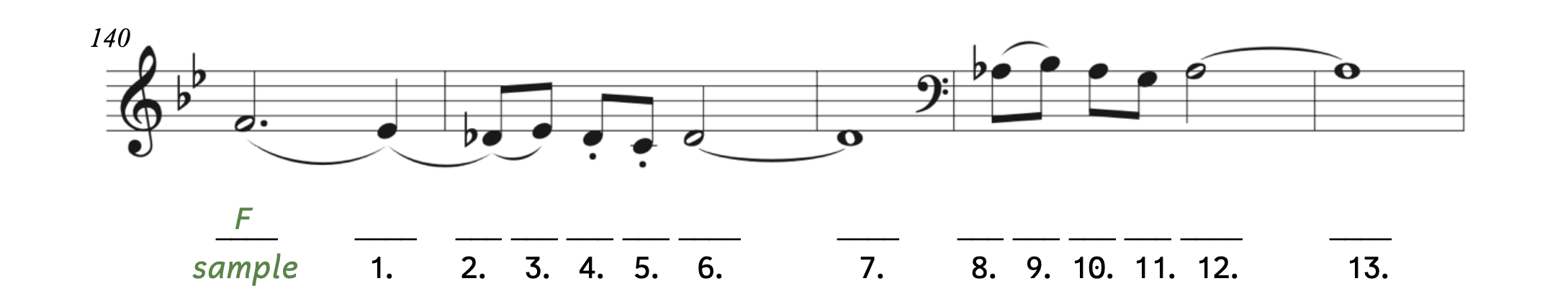

Practice 4.5A. Identifying Pitches with a Key Signature

Directions:

- Identify the pitches on the staff in the blanks below.

Bosmans, Impressions for Cello and Piano, I. Cortège

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) D

3) E

4) D

5) C

6) D

7) D

8) A

9) B

10) A

11) G

12) A

13) A

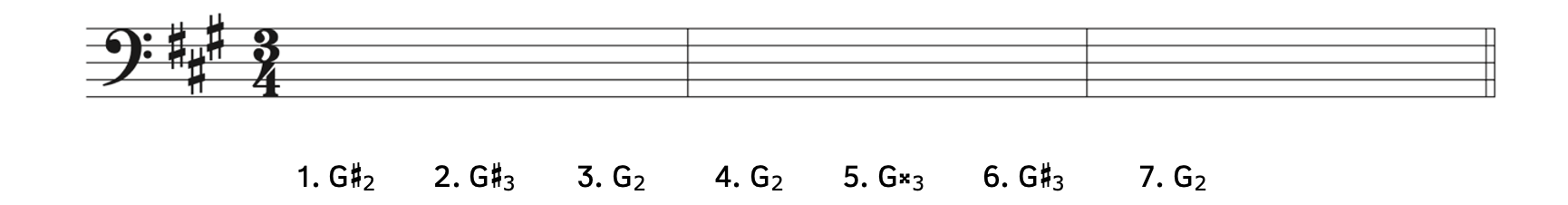

Practice 4.5B. Writing Pitches with a Key Signature

Directions:

- Write the given pitches using correct rhythm.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

4.6 MAJOR KEY SIGNATURES WITH FLATS

Accidentals in key signatures must appear in a specific order and they must be placed on specific locations within the staff. Identifying and writing key signatures quickly is one of the biggest hurdles for students. However, if you are able to quickly identify and write all the major and minor key signatures, music theory will be much easier for you. Key signatures will have either flats or sharps, not both. We will begin with major key signatures with flats.

Flats in major (and minor) key signatures always appear in this order:

One of the easiest ways to remember the order of flats is that it spells “BEAD” followed by “GCF” (“Greatest Common Factor”). You can also use other mnemonics to help you memorize the order of flats, such as “Before Eating A Donut Get Coffee First.” Ultimately, you need to just simply memorize the order of flats.

The order of flats is very important. For example, if there are three flats, the following statements will always be true:

- The three flats are always B

, E

, E , and A

, and A .

. - The three flats will never be other pitches. For example, they will never be B

, E

, E , and D

, and D .

. - The three flats will never be in any other order. For example, they will never be B

, A

, A , then

, then  .

.

Once you have the order of flats memorized, you need to learn their exact placement on the grand staff. Each flat sits on a specific line or space in the treble clef and in the bass clef. For instance, the first flat is always written on B4 in the treble clef and B2 in the bass clef. It is incorrect to write them anywhere else.

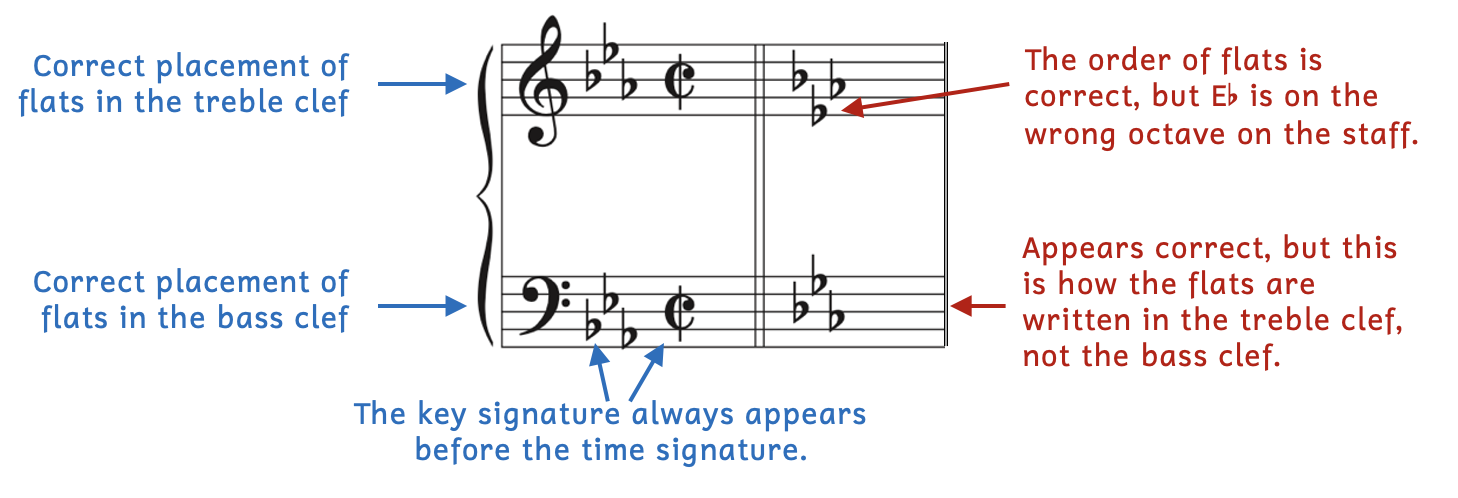

The major key with three flats is E-flat major. Example 4.6.1 illustrates correctly- and incorrectly-written key signatures.

Example 4.6.1. Key signature for E-flat major

First, notice the parts that are correctly written (in blue).

- The key signature is correctly written on the staff in both the treble clef and bass clef.

- The key signature always appears before the time signature. An easy way to remember the order is that alphabetically, the word “key” comes before the word “time.”

Now, focus on the second measure, which shows two of the most common key signature errors students make (in red).

- In the treble clef, the order of flats is correct, but E

, which should be written at E

, which should be written at E 5, is written incorrectly at E

5, is written incorrectly at E 4.

4. - In the bass clef, the key signature is perfectly written for treble clef. Based on the bass clef, the placement of the flats here say that the three flats are D

, G

, G , and C

, and C .

.

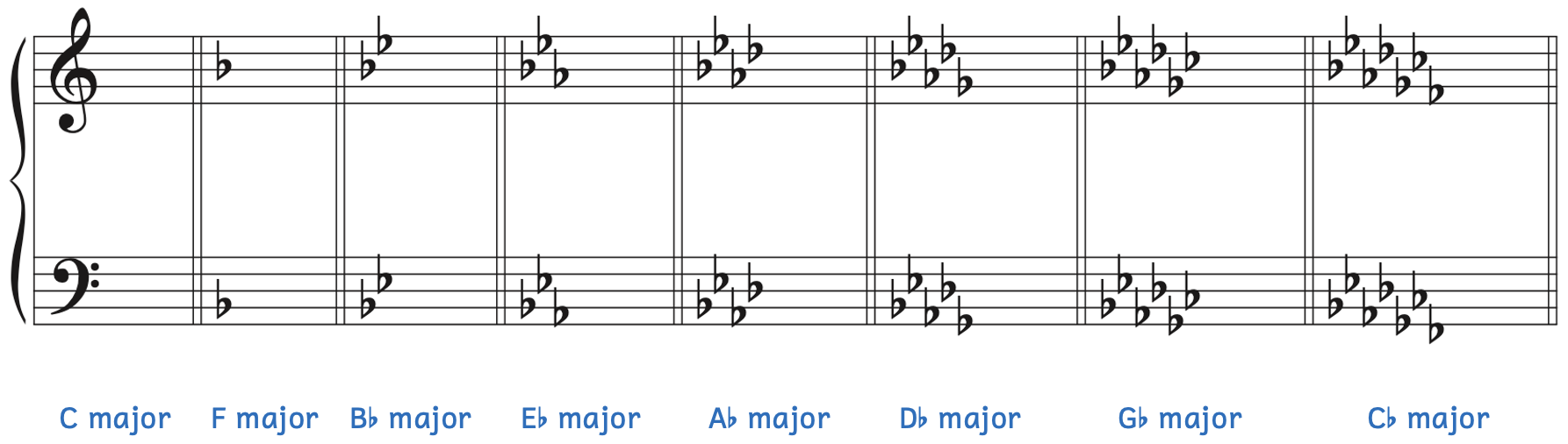

Since there are seven different note names, there can be a maximum of seven flats in a key signature. The example below shows all the major key signatures with flats.

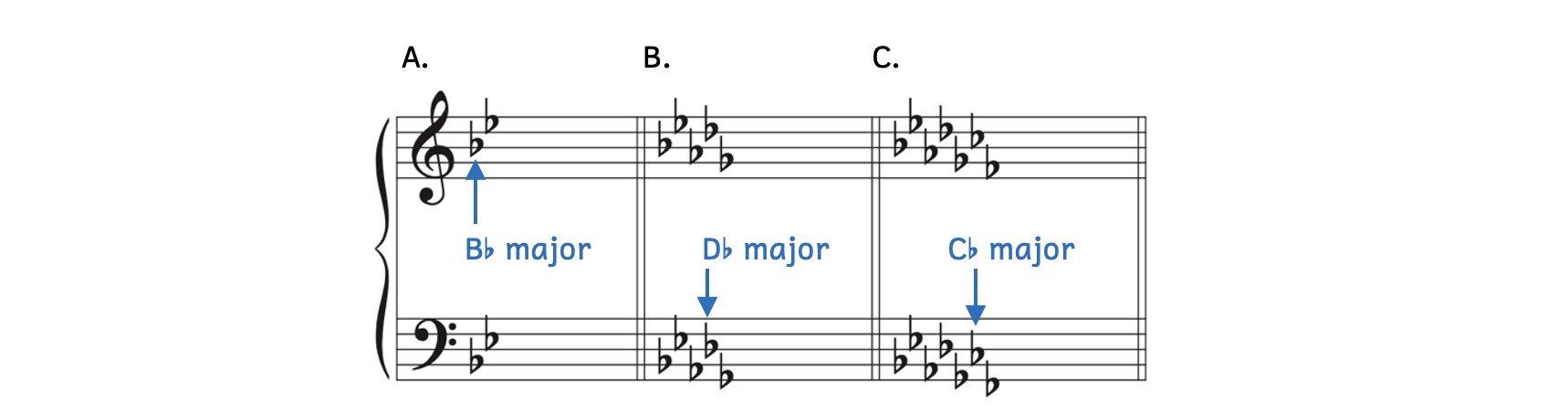

Example 4.6.2. Major key signatures from zero to seven flats

There are several clues that can help you quickly memorize the major key signatures with flats:

- C major has zero flats while C

major has seven flats.

major has seven flats. - All the major keys with flats have a flatted tonal center except for F (e.g., B

major and G

major and G major).

major).

- In other words, all keys with flats have “flat” in their names except for F major.

- Notice the pattern of flats: flats alternate up–down to create descending pairs.

- Treble clef begins on B

4 and the pattern is up–down.

4 and the pattern is up–down. - Bass clef begins on B

2 and the pattern is the same: up–down.

2 and the pattern is the same: up–down. - For C

major, the pattern of flats is 2+2+2+1.

major, the pattern of flats is 2+2+2+1.

- Treble clef begins on B

One of the best ways to practice memorizing the correct placement of key signatures on the staff is to be able to write C![]() major quickly by memory. If you can write all seven flats correctly in both treble clef and bass clef, writing fewer flats should be a cinch.

major quickly by memory. If you can write all seven flats correctly in both treble clef and bass clef, writing fewer flats should be a cinch.

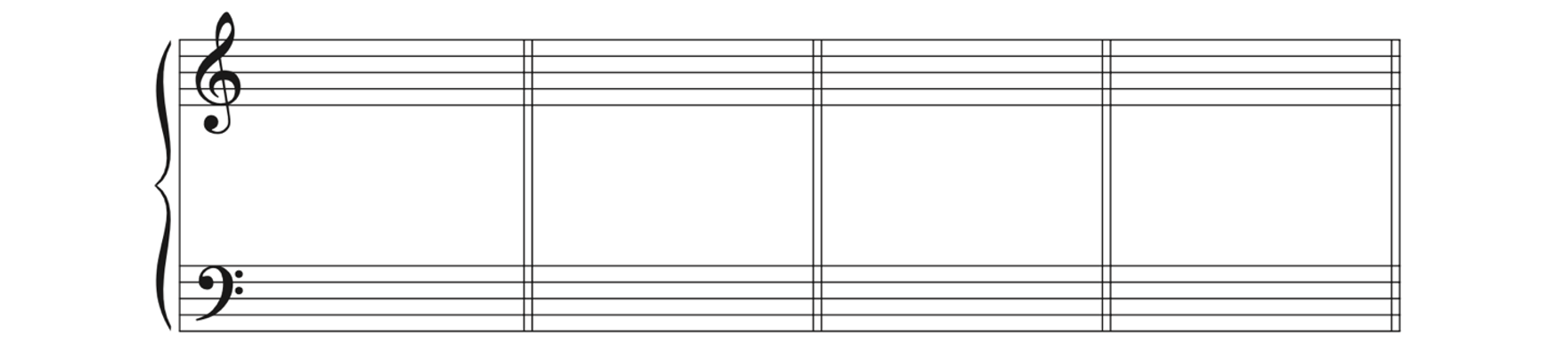

Practice 4.6A. Writing the C-Flat Major Key Signature

Directions:

- Write the key signature for C

major until you are able to do so quickly and by memory.

major until you are able to do so quickly and by memory.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Until you memorize all seven major key signatures with flats, you can use a shortcut. With the exception of F major, the shortcut is that the key is the penultimate (second-to-last) flat.

Example 4.6.3. Penultimate flat = key

- Example 4.6.3A: The penultimate flat is B

, so the key is B

, so the key is B major.

major. - Example 4.6.3B: The penultimate flat is D

, so the key is D

, so the key is D major.

major. - Example 4.6.3C: The penultimate flat is C

, so the key is C

, so the key is C major.

major.

- Sometimes students call this B major because B and C

are enharmonically equivalent (i.e., the same key on the piano). However, calling it B major would be incorrect since the first flat in the key signature is B

are enharmonically equivalent (i.e., the same key on the piano). However, calling it B major would be incorrect since the first flat in the key signature is B . It would be impossible for B major to have any flats since the first flat is always B

. It would be impossible for B major to have any flats since the first flat is always B .

.

- Sometimes students call this B major because B and C

The reason why we could not use the shortcut for F major is because F major only has one flat, so there is no penultimate flat.

Now we will put together everything we have learned to figure out the key of a musical example.

Example 4.6.4. Finding the key: Szymanowska[10], March No. 5

When figuring out the key of a given musical example, follow these steps:

- Listen to the example: Does it sounds like it’s in major (happy)?

- Yes, Example 4.6.4 sounds like it is in major.

- Look at the key signature.

- The key signature has two flats, which is the key of B

major.

major.

- The key signature has two flats, which is the key of B

- Look at the first lowest note.

- The first lowest note is B

.

.

- The first lowest note is B

- Look at the last lowest note.

- The last lowest note is B

.

.

- The last lowest note is B

In Example 4.6.4, all four steps point to B![]() major. Using the first lowest note and the last lowest notes are not always reliable, but are more dependable when put together with the other steps.

major. Using the first lowest note and the last lowest notes are not always reliable, but are more dependable when put together with the other steps.

Strategies for Major Key Signatures with Flats

- Memorize the order of flats: B

– E

– E – A

– A – D

– D – G

– G – C

– C – F

– F

- Memorize the key signatures for all the major keys with flats.

- Be able to quickly identify major keys by their key signatures. The penultimate flat is the key.

- Be able to quickly write the key signature for C

major for treble clef and bass clef. If you can write the key signature for all seven flats, then you can write all the major key signatures with flats.

major for treble clef and bass clef. If you can write the key signature for all seven flats, then you can write all the major key signatures with flats.

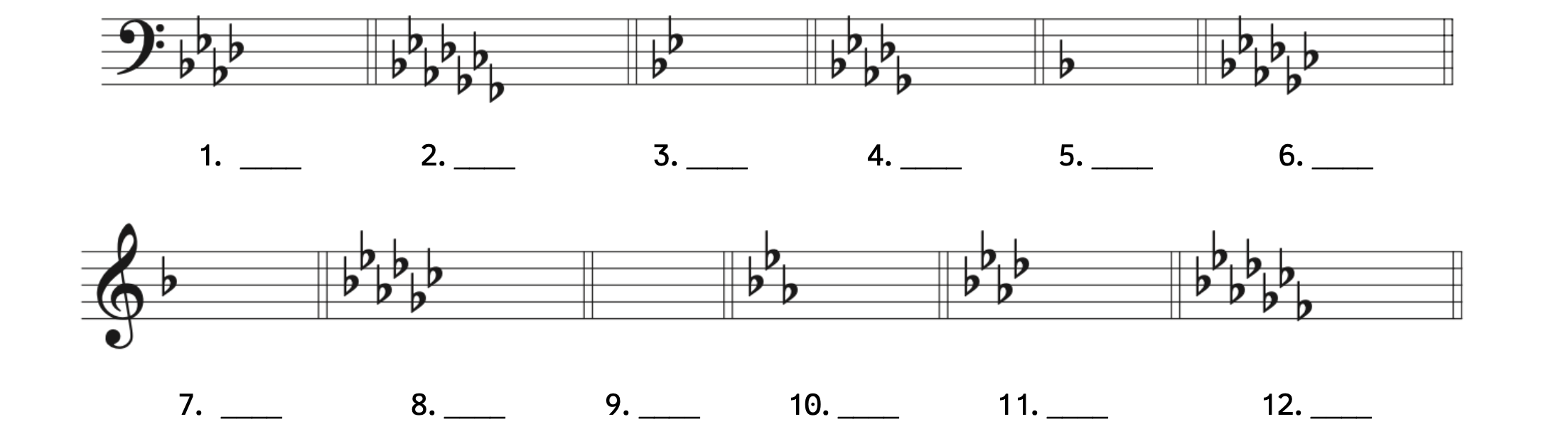

Practice 4.6B. Identifying Major Key Signatures with Flats

Directions:

- Identify the major keys. For major keys, you only need to write an uppercase letter (e.g., F).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) C

3) B

4) D

5) F

6) G

7) F

8) G

9) C

10) E

11) A

12) C

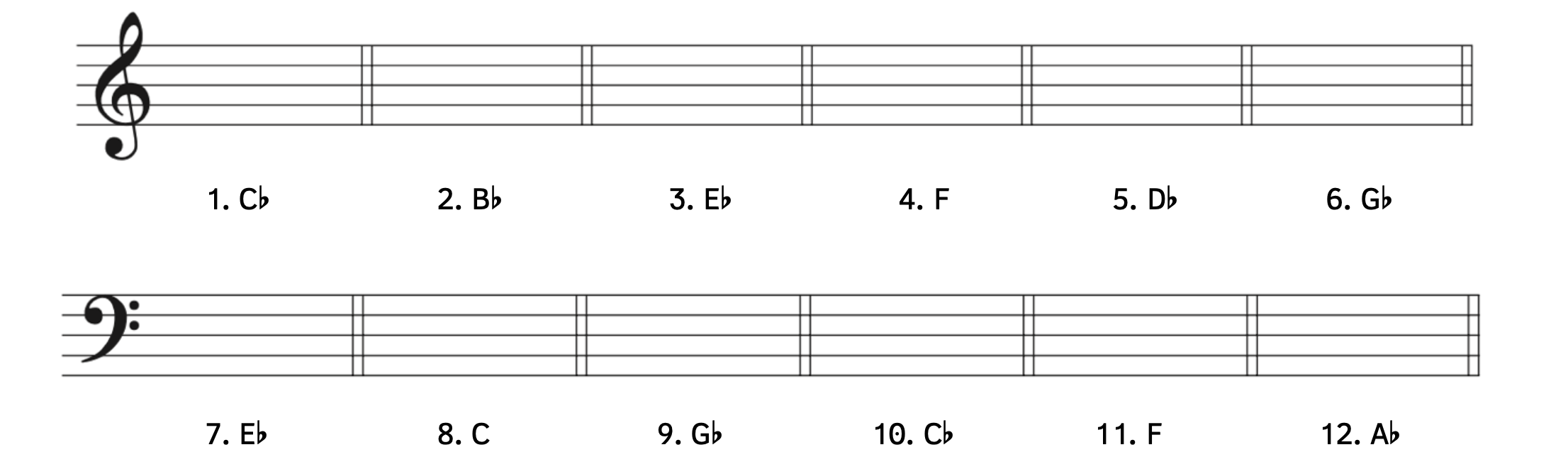

Practice 4.6C. Writing Major Key Signatures with Flats

Directions:

- Write the given key signatures on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

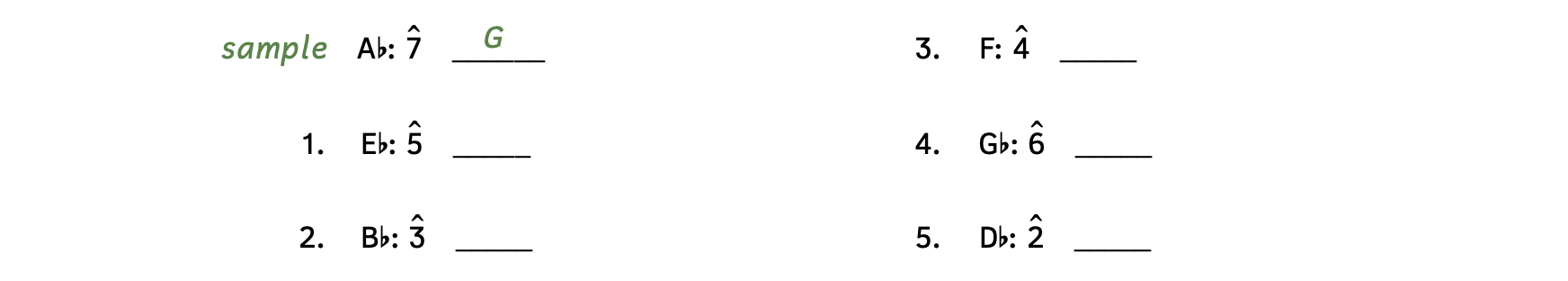

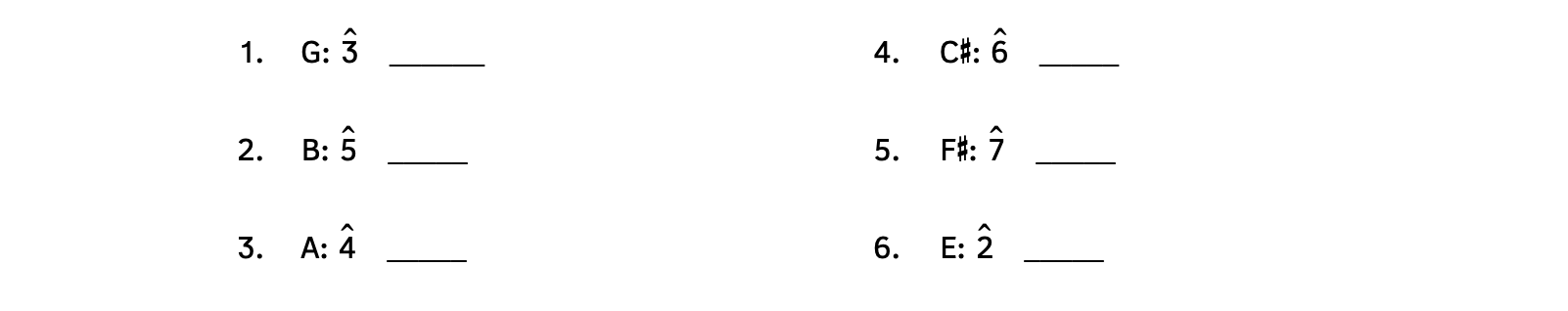

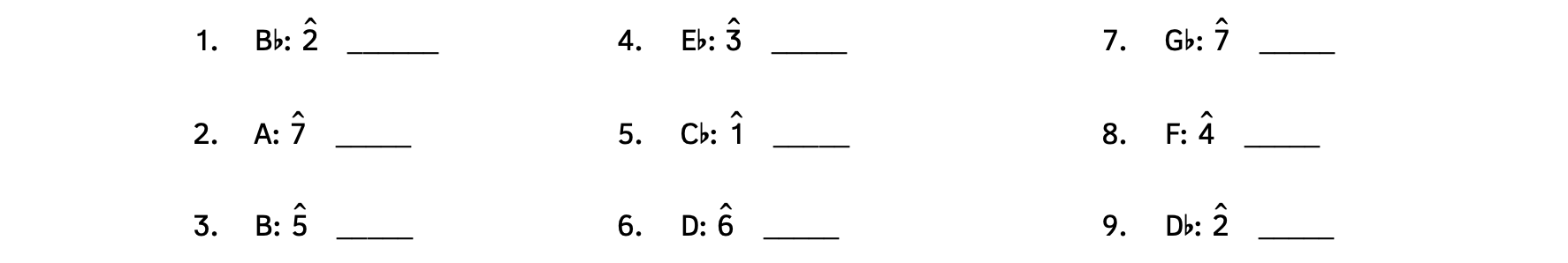

Practice 4.6D. Identifying Pitches by Scale Degrees in Major Flat Keys

Directions:

- In the given keys, write the pitch of the given scale degree number.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) D

3) B

4) E

5) E

4.7 MAJOR KEY SIGNATURES WITH SHARPS

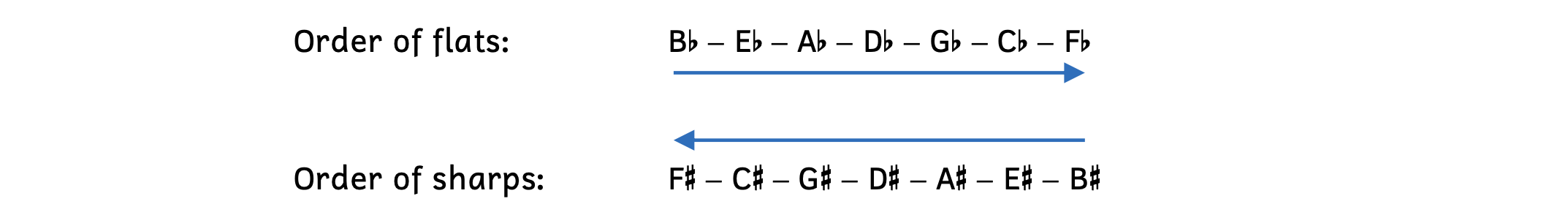

Just as flats in key signatures must appear in a specific order and must be placed on specific locations within the staff, so must sharps in key signatures. Sharps in major (and minor) key signatures always appear in this order:

One of the easiest ways to remember the order of sharps is that it is the order of flats backwards.

You can also use other mnemonics to help you memorize the order of sharps, such as “Fat Cats Get Drunk And Eat Birds.” Ultimately, you need to just memorize the order of sharps.

The order of sharps tells us that if there are six sharps, they are always F![]() , C

, C![]() , G

, G![]() , D

, D![]() , A

, A![]() , and E

, and E![]() in that order. Once you have the order of sharps memorized, you need to learn their exact placement on the grand staff. Each sharp sits on a specific line or space in the treble clef and in the bass clef. For example, the first sharp is always written on F5 in the treble clef and F3 in the bass clef. It is incorrect to write them anywhere else.

in that order. Once you have the order of sharps memorized, you need to learn their exact placement on the grand staff. Each sharp sits on a specific line or space in the treble clef and in the bass clef. For example, the first sharp is always written on F5 in the treble clef and F3 in the bass clef. It is incorrect to write them anywhere else.

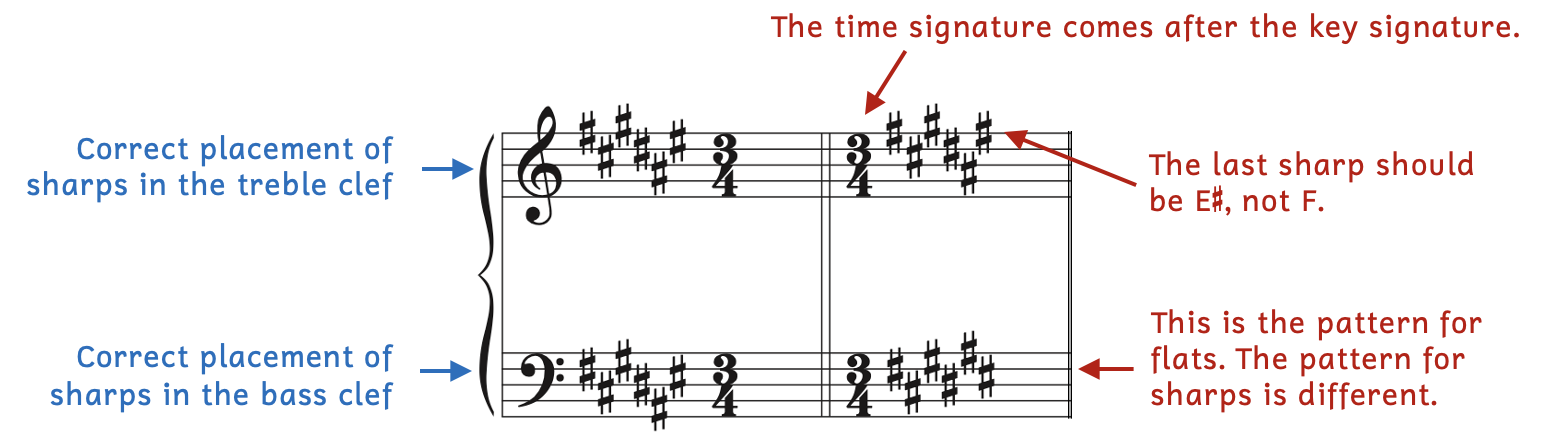

The major key with six sharps flats is F![]() major. Example 4.7.1 illustrates correctly- and incorrectly-written key signatures.

major. Example 4.7.1 illustrates correctly- and incorrectly-written key signatures.

Example 4.7.1. Key signature for F-sharp major

The first measure shows the key signature correctly written (in blue). The second measure illustrates some of the most common key signature errors students make (in red):

- The time signature always comes after the key signature. Remember that the word “key” comes before the word “time” alphabetically.

- In the treble clef, the last sharp is E

, not F. Sometimes students think it is easier to write F, but that is incorrect.

, not F. Sometimes students think it is easier to write F, but that is incorrect.

- F

is already the first sharp in the key signature.

is already the first sharp in the key signature. - The enharmonic equivalent of E

is actually F

is actually F , and not F

, and not F .

.

- F

- In the bass clef, the key signature is written in pairs, as if for treble clef. The pattern for key signatures with sharps is different.

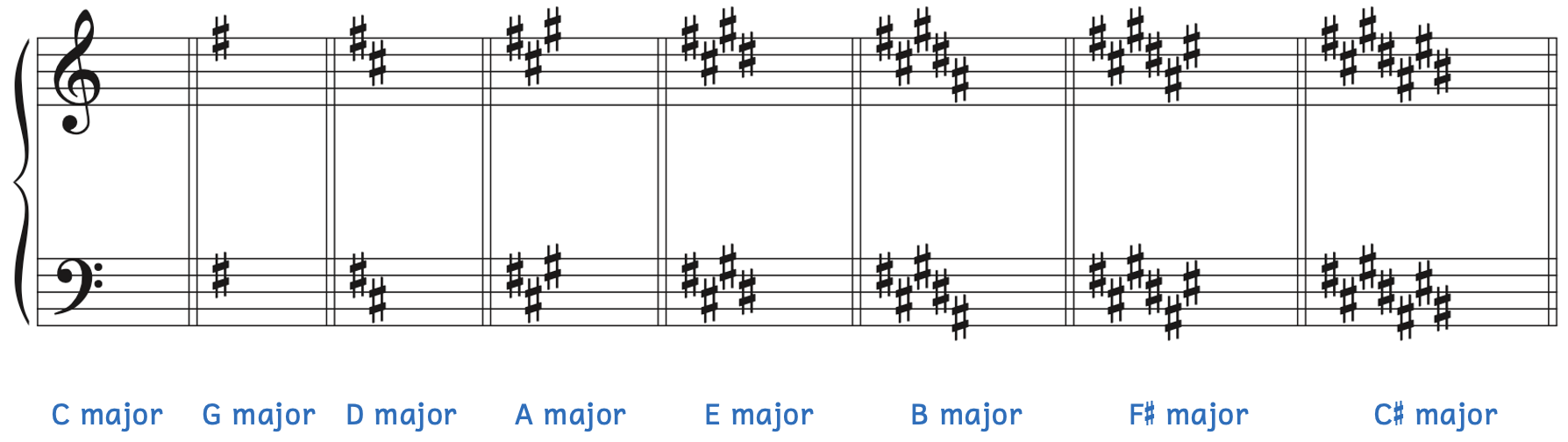

Since there are seven different note names, there can be a maximum of seven sharps in a key signature. The example below shows all the major key signatures with sharps.

Example 4.7.2. Major key signatures from zero to seven sharps

There are several clues that can help you quickly memorize the major key signatures with sharps:

- C major has zero sharps while C

major has seven sharps.

major has seven sharps. - All the major keys with sharps do not have a sharped tonal center except for F

and C

and C major (e.g., G major and B major).

major (e.g., G major and B major).

- In other words, none of the keys with sharps have “sharp” in their names except for F

major and C

major and C major.

major.

- In other words, none of the keys with sharps have “sharp” in their names except for F

- The pattern of sharps is different than the pattern of flats.

- The treble clef begins on F

5 and the bass clef begins on F

5 and the bass clef begins on F 3.

3. - The pattern begins down–up, but is then followed by down–down–up.

- For C

major, the pattern of sharps is 2+3+2.

major, the pattern of sharps is 2+3+2.

- The treble clef begins on F

One of the best ways to practice memorizing the correct placement of key signatures on the staff is to be able to write C![]() major quickly by memory. If you can write all seven sharps correctly in both treble clef and bass clef, writing fewer sharps should be easy.

major quickly by memory. If you can write all seven sharps correctly in both treble clef and bass clef, writing fewer sharps should be easy.

Practice 4.7A

Directions:

- Write the key signature for C-sharp major until you are able to do so quickly and by memory.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

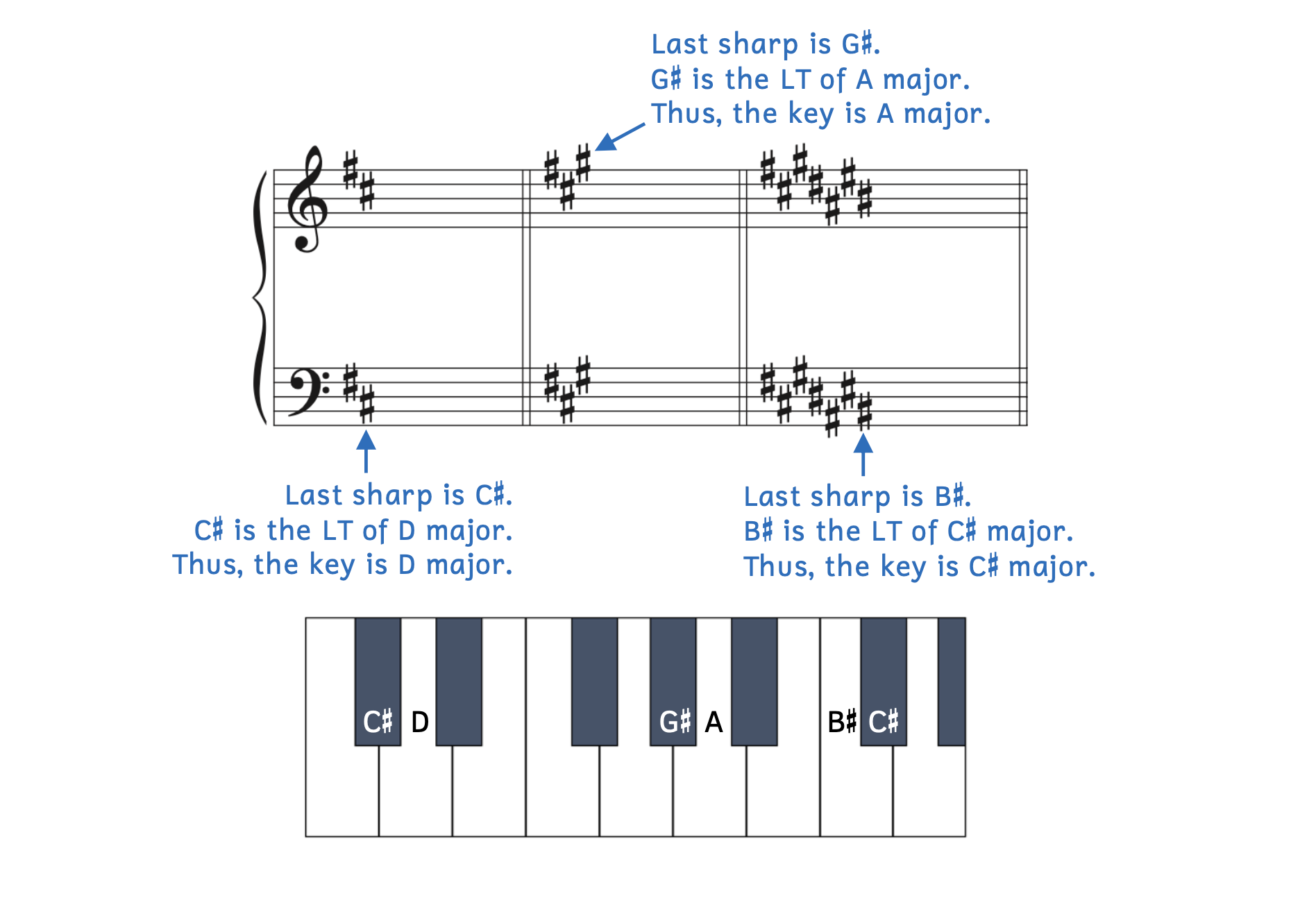

Until you memorize all seven major key signatures with sharps, you can use a shortcut. For all the major keys with sharps, the last sharp is a diatonic half step below the tonic. In other words, the last sharp is the leading tone (LT) of the key.

Example 4.7.3. Last sharp = leading tone

- In the first measure, the last sharp is C

. C

. C is a diatonic half step below D, so the key is D major.

is a diatonic half step below D, so the key is D major. - In the second measure, the last sharp is G

. G-sharp is the leading tone of A major, so the key is A major.

. G-sharp is the leading tone of A major, so the key is A major. - In the final measure, the last sharp is B

. B

. B is a diatonic half step below C

is a diatonic half step below C , not C. Therefore, the key is C

, not C. Therefore, the key is C major.

major.

- Remember that every note in C

major has a sharp.

major has a sharp.

- Remember that every note in C

Apply the steps we learned in the last section to figure out the key of a musical example.

Example 4.7.4. Find the key: Szymanowska, March No. 3[11]

- Listen to the example: Does it sounds like it’s in major (happy)?

- Yes, Example 4.7.4 sounds like it is in major.

- Look at the key signature.

- The key signature has two sharps, which is the key of D major.

- Look at the first lowest note.

- The first lowest note is A.

- Look at the last lowest note.

- The last lowest note is D.

In Example 4.7.4, step 3 does not agree with D major. However, if we look at the music, the first lowest note (A) is an anacrusis. We know that the anacrusis leads into the downbeat and the downbeat is much stronger. If we take the downbeat into consideration instead, we see that the first lowest note is actually D. Example 4.7.4 is in D major.

Strategies for Major Key Signatures with Sharps

- Memorize the order of sharps: F

– C

– C – G

– G – D

– D – A

– A – E

– E – B

– B

- Memorize the key signatures for all the major keys with sharps.

- Be able to quickly identify major keys by their key signature. The last sharp is the leading tone of the key.

- Be able to quickly write the key signature for C

major for the treble clef and bass clef. If you can write the key signature for all seven sharps, then you can write all the major key signatures with sharps.

major for the treble clef and bass clef. If you can write the key signature for all seven sharps, then you can write all the major key signatures with sharps.

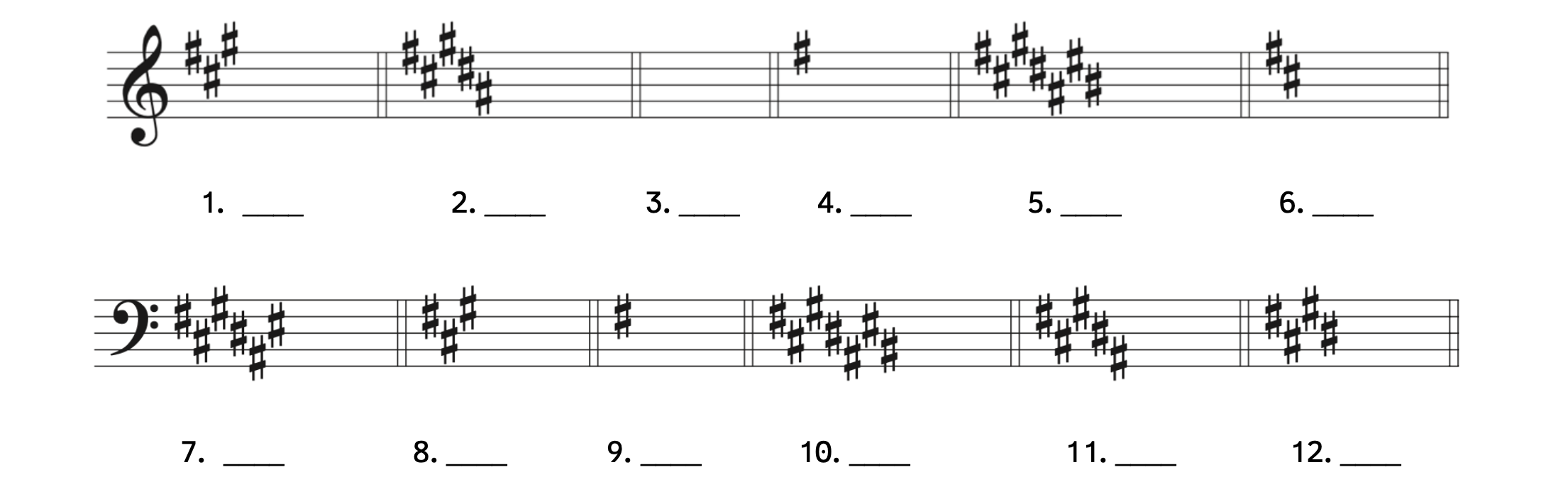

Practice 4.7B. Identifying Major Key Signatures with Sharps

Directions:

- Identify the major keys. For major keys, you only need to write an uppercase letter (e.g., G).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) B

3) C

4) G

5) C

6) D

7) F

8) A

9) G

10) C

11) B

12) E

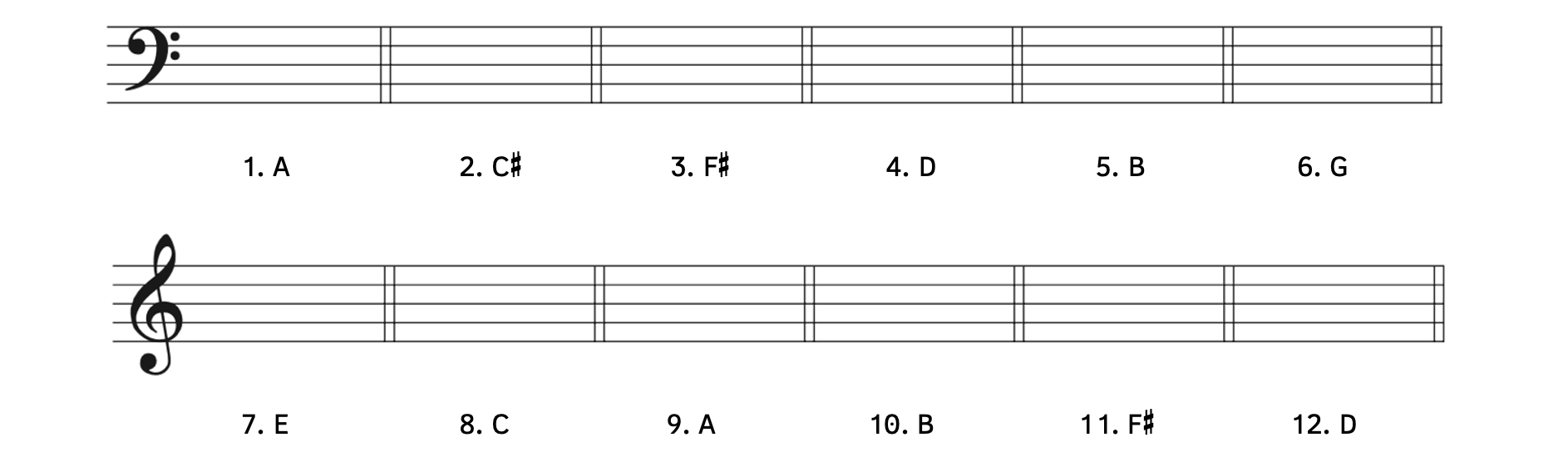

Practice 4.7C. Writing Major Key Signatures with Sharps

Directions:

- Write the given key signatures on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

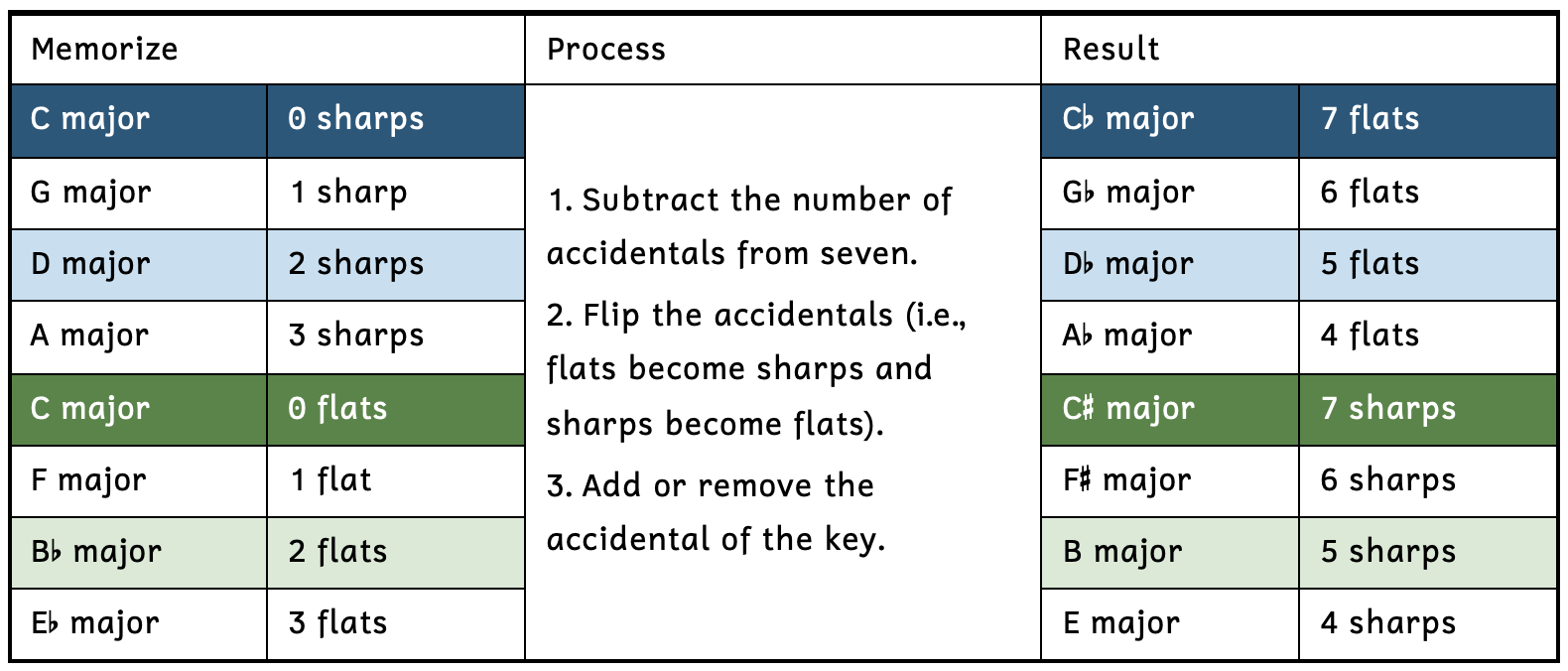

Practice 4.7D. Identifying Pitches by Scale Degrees in Major Sharp Keys

Directions:

- In the given keys, write the pitch of the given scale degree number.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) F

3) D

4) A

5) E

6) F

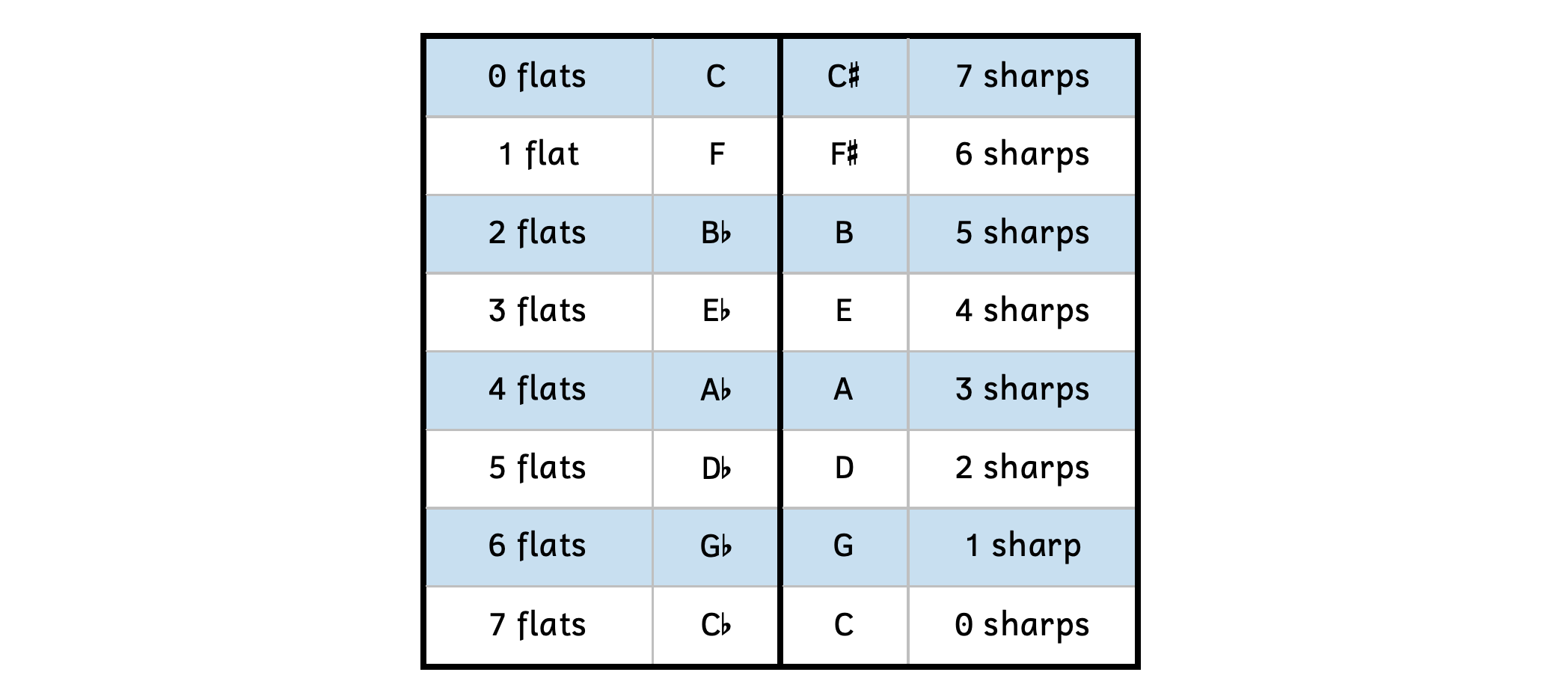

Notice the pattern between major keys with flats and major keys with sharps.

Example 4.7.5. Major keys comparison

- Reading across, the letter names of the keys are the same, but one has an accidental.

- e.g., F and F

or D

or D and D

and D

- e.g., F and F

- The number of accidentals equals seven.

- e.g., 1 flat + 6 sharps or 5 flats + 2 sharps

- C is the only note name that appears three times.

- C major = 0; C

major = 7 flats; C

major = 7 flats; C major = 7 sharps

major = 7 sharps

- C major = 0; C

- F is the only flat key without “flat” in its name.

If you understand this pattern, you can focus on only memorizing major keys with three accidentals as a starting point (Example 4.7.6).

Example 4.7.6. Memorizing up to three accidentals

In order to use this tip, you must know which keys have sharps and which keys have flats.

- If you memorize that D major has two sharps:

- 7 – 2 = 5

- Flip the accidentals: 5 flats

- Add or remove the accidental of the key: D becomes D

- The new key cannot be D

major because there is no such key as D

major because there is no such key as D major, and the new key signature has flats.

major, and the new key signature has flats.

- The new key cannot be D

- Therefore, if D major has two sharps, D

major has five flats.

major has five flats.

- If you memorize that F major has one flat:

- 7 – 1 = 6

- Flip the accidentals: 6 sharps

- Add or remove the accidental of the key: F becomes F

- The new key cannot be F

major because there is no such key as F

major because there is no such key as F major, and the new key signature has sharps.

major, and the new key signature has sharps.

- The new key cannot be F

- Therefore, if F major has one flat, F

major has six sharps.

major has six sharps.

- If you memorize that E

major has three flats:

major has three flats:

- 7 – 3 = 4

- Flip the accidentals: 4 sharps

- Add or remove the accidental of the key: E

becomes E

becomes E

- The new key cannot be E

major because there is no such key as E

major because there is no such key as E major.

major.

- The new key cannot be E

- Therefore, if E

major has three flats, E major has four sharps.

major has three flats, E major has four sharps.

You can also use this method when identifying key signatures.

- If you are given six flats, but cannot remember the key.

- 7 – 6 = 1

- Flip the accidentals: 1 sharp

- G major has one sharp. Now add or remove the accidental of the key: G becomes G

.

.

- The key cannot be G

major because there is no such key as G

major because there is no such key as G major, and the given key signature has flats.

major, and the given key signature has flats.

- The key cannot be G

- Therefore, six flats is the key of G

major because G major has one sharp.

major because G major has one sharp.

- If you see five sharps, but cannot remember the key.

- 7 – 5 = 2

- Flip the accidentals: 2 flats

- B

major has two flats. Now add or remove the accidental of the key: B

major has two flats. Now add or remove the accidental of the key: B becomes B.

becomes B.

- The key cannot be B

major because there is no such key as B

major because there is no such key as B major.

major.

- The key cannot be B

- Therefore, five sharps is the key of B major because B

major has two flats.

major has two flats.

Although you can use this tip when you are starting out, your goal is to confidently know all the major key signatures without any tricks or steps.

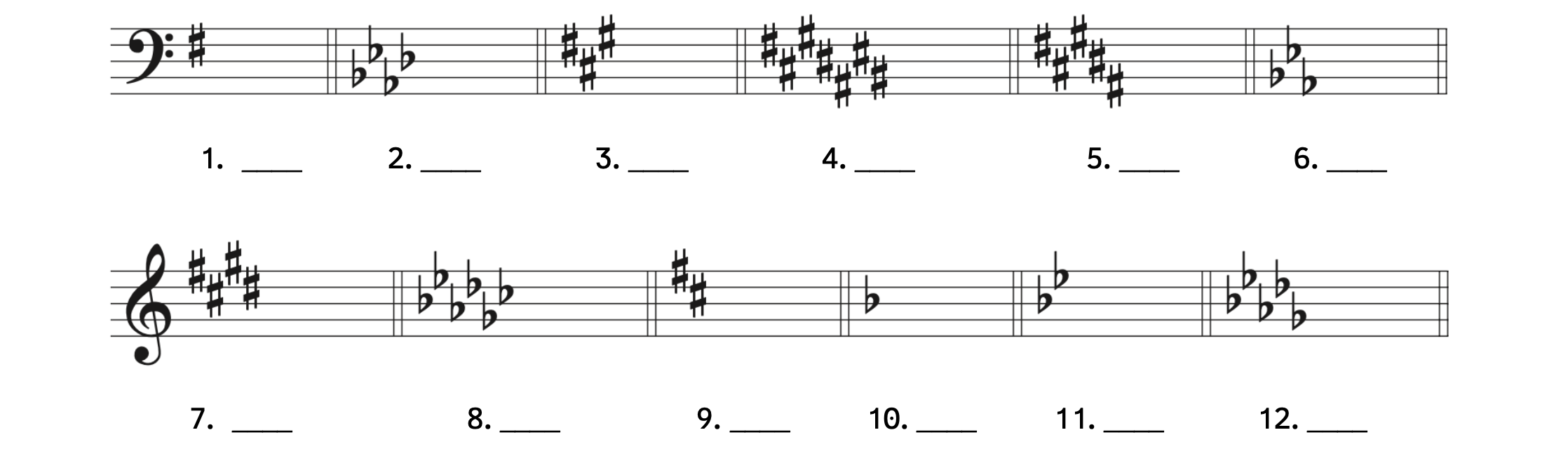

Practice 4.7E. Identifying Major Key Signatures

Directions:

- Identify the major keys. For major keys, you only need to write an uppercase letter (e.g., E).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) A

3) A

4) C

5) B

6) E

7) E

8) G

9) D

10) F

11) B

12) D

Practice 4.7F. Writing Major Key Signatures

Directions:

-

Write the given key signatures on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 4.7G. Identifying Pitches by Scale Degrees in Major Keys

Directions:

- In the given keys, write the pitch of the given scale degree number.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) G

3) F

4) G

5) C

6) B

7) F

8) B

9) E

4.8 CIRCLE OF FIFTHS

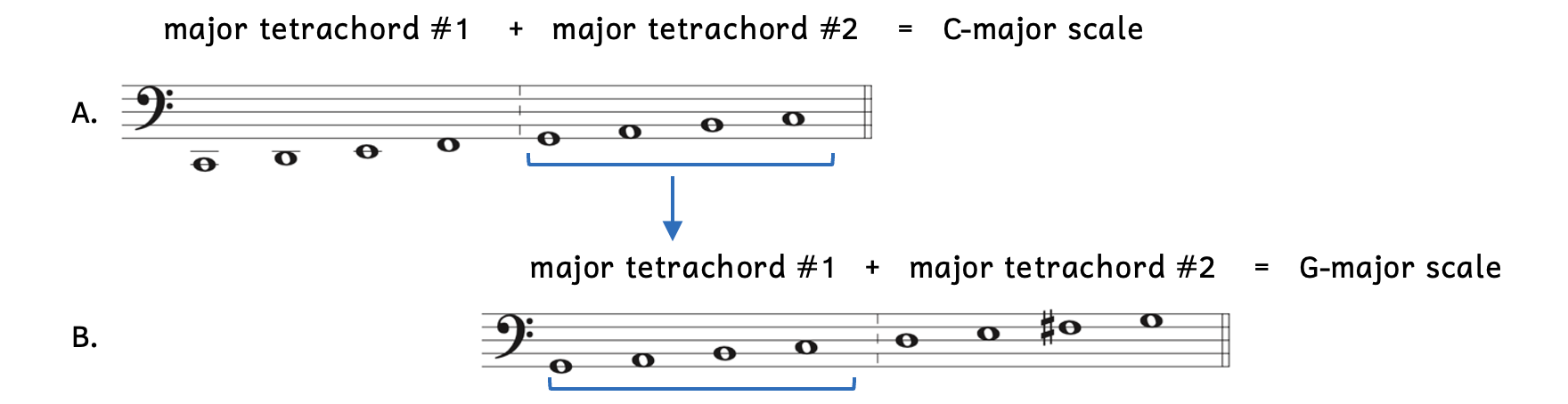

Recall that we can create major scales by writing two major tetrachords with a whole step in between. Notice what happens when we use the second major tetrachord of a C major scale as the first major tetrachord of another major scale. It creates the G major scale (Example 4.8.1).

Example 4.8.1. Forming a new major scale

- Example 4.8.1A:

- Major tetrachord #1 begins on C. After a whole step, major tetrachord #2 begins on G and ends on C.

- The result is a C major scale.

- There are no accidentals in the C major scale, thus the key of C major has no sharps or flats.

- Example 4.8.1B:

- Major tetrachord #2 from Example 4.8.1A now becomes major tetrachord #1.

- Major tetrachord #1 begins on G, which is a fifth higher than Example 4.8.1A’s major tetrachord #1. After a whole step, major tetrachord #2 begins on D and ends on G.

- The result is a G major scale.

- There is one sharp (F

) in the G major scale, thus the key of G major has one sharp.

) in the G major scale, thus the key of G major has one sharp.

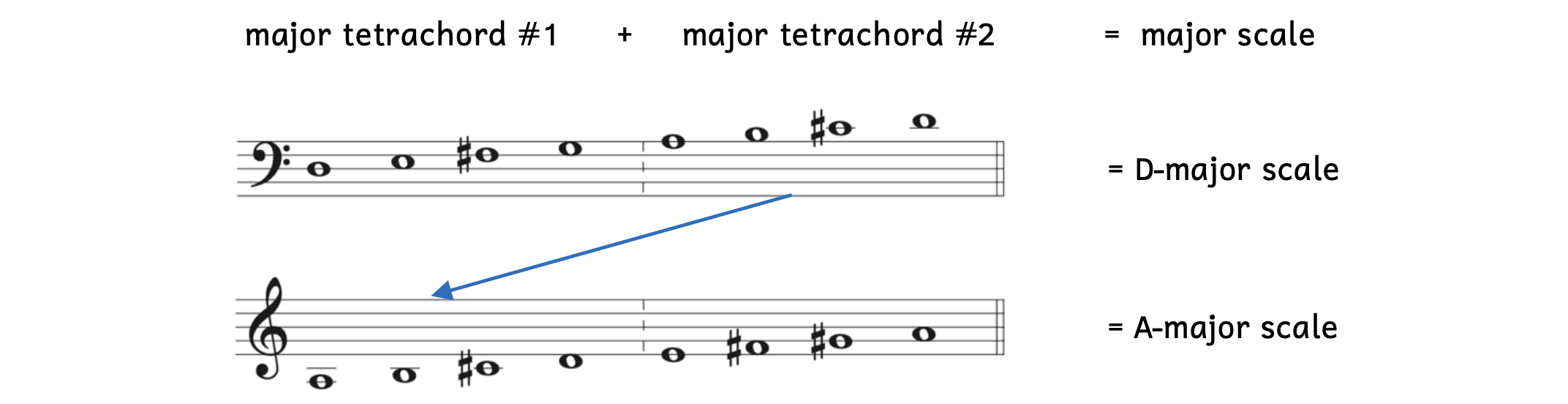

We can continue this pattern by making Example 4.8.1B’s major tetrachord #2 into a major tetrachord #1 to create a D major scale, and so on (Example 4.8.2).

Example 4.8.2. Continuation of Example 4.8.1

Each new major scale is a fifth higher and contains one more sharp. In fact, we can continue this pattern until we return to C major. Each new scale will be a fifth higher than the previous. This important relationship can be illustrated by the circle of fifths.

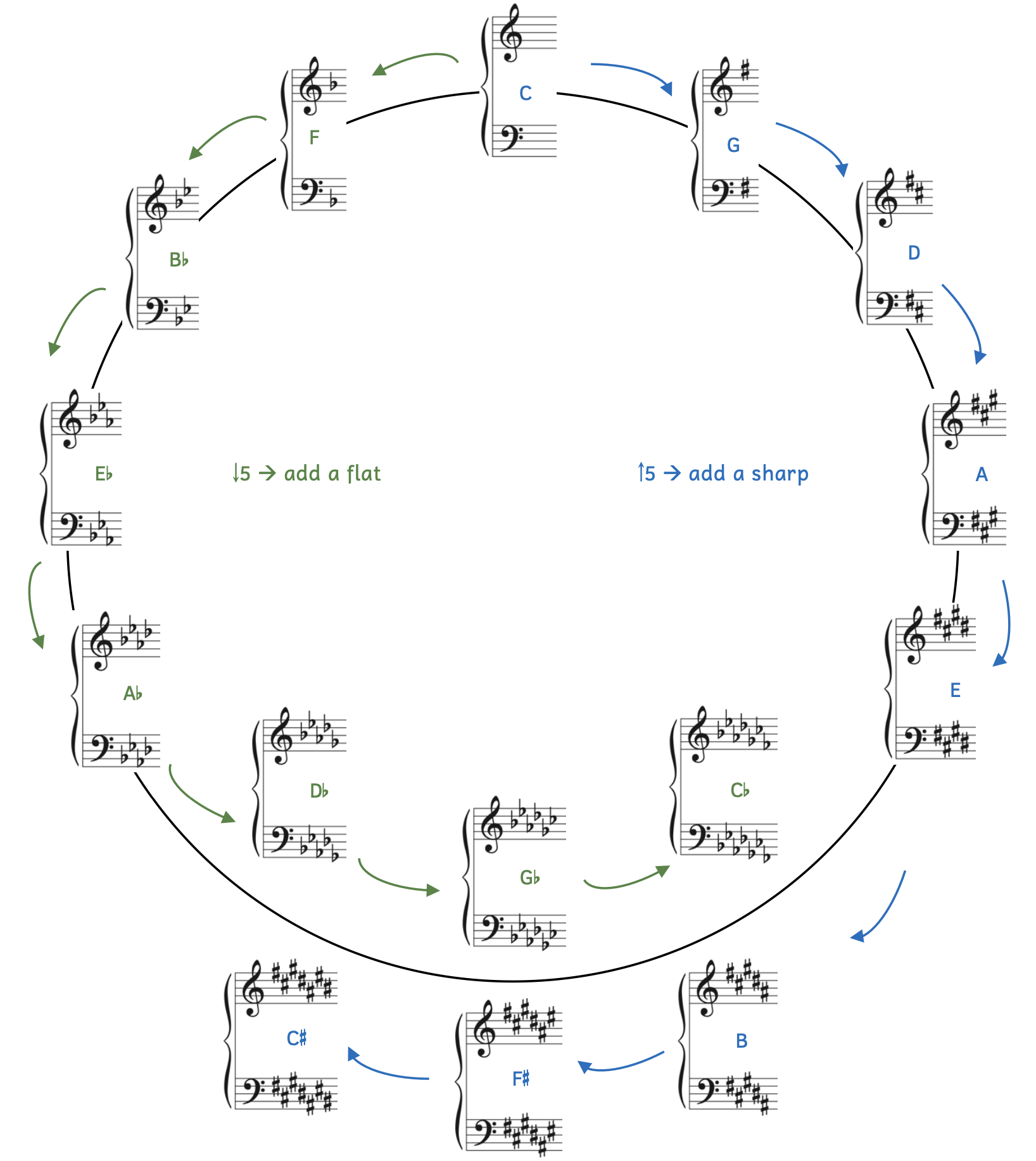

Example 4.8.3. Circle of fifths

There is a wealth of information in the circle of fifths.

- Moving clockwise from C:

- Each key is a fifth higher.

- A fifth above E is B.

- Each key adds a sharp.

- E major has 4 sharps and B major has 5 sharps.

- C (no sharps, no flats) moves clockwise to C

major (7 sharps).

major (7 sharps).

- Each key is a fifth higher.

- Moving counterclockwise from C:

- Each key is a fifth lower.

- A fifth below E

is A

is A .

.

- A fifth below E

- Each key adds a flat.

- E

major has 3 flats and A

major has 3 flats and A major has 4 flats.

major has 4 flats.

- E

- C (no sharps, no flats) moves counterclockwise to C

major (7 flats).

major (7 flats).

- Each key is a fifth lower.

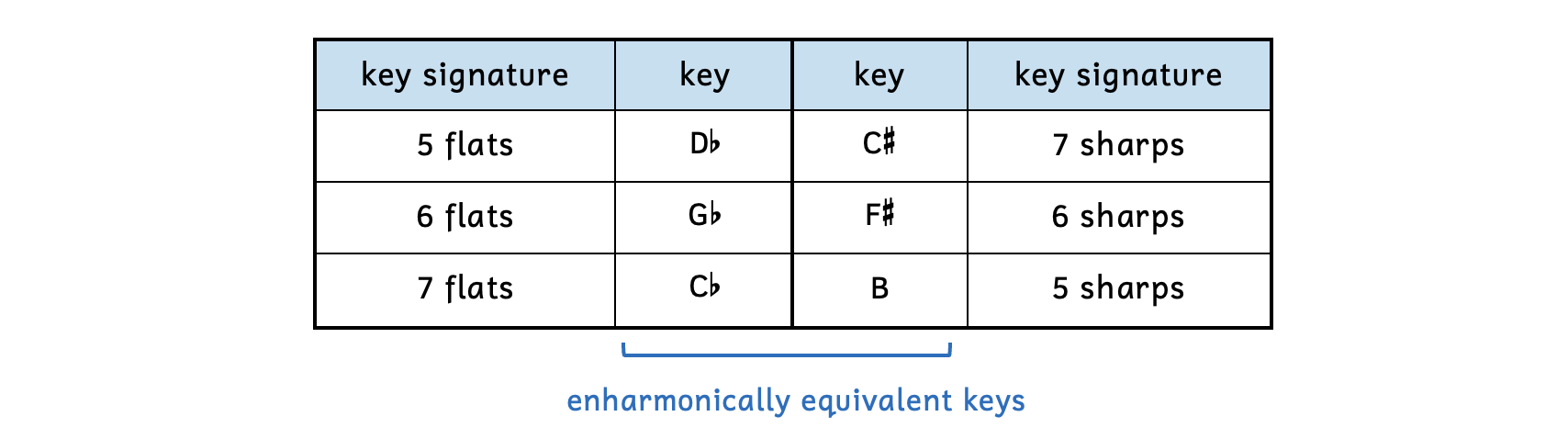

There are three keys on the bottom of the circle of fifths that have two keys. This is because these keys are enharmonically equivalent keys.

Example 4.8.4. Enharmonically equivalent keys

D![]() is enharmonically equivalent to C

is enharmonically equivalent to C![]() so the key of D

so the key of D![]() major is also enharmonically equivalent to the key of C

major is also enharmonically equivalent to the key of C![]() major. However, since D

major. However, since D![]() must have flats (because its tonic is D

must have flats (because its tonic is D![]() ) and C

) and C![]() must have sharps (because its tonic is C

must have sharps (because its tonic is C![]() ), D

), D![]() has five flats and C

has five flats and C![]() has seven sharps. You can refer back to Example 4.1 to see how every member of these keys are enharmonically equivalent.

has seven sharps. You can refer back to Example 4.1 to see how every member of these keys are enharmonically equivalent.

If we continue along the circle of fifths beyond C![]() major, the next key a fifth above would be G

major, the next key a fifth above would be G![]() major. However, G

major. However, G![]() major does not exist. Instead, the next key after C

major does not exist. Instead, the next key after C![]() major is A

major is A![]() major, which exists and is an enharmonically equivalent key to G

major, which exists and is an enharmonically equivalent key to G![]() major. Therefore, the circle of fifths still continues from C

major. Therefore, the circle of fifths still continues from C![]() major to A

major to A![]() major, with A

major, with A![]() major being enharmonically equivalent.

major being enharmonically equivalent.

Although there is a wealth of information in the circle of fifths, sometimes students depend on it rather than simply memorizing key signatures. Indeed, I have often witnessed students wasting five precious minutes of exam time recreating the entire circle of fifths. It is more beneficial as musicians for you to take the time now to memorize the fifteen major key signatures as quickly as possible.

Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths is a graphic representation of how all the major keys are built by moving up or down by five. Each key either gains a sharp (clockwise) or gains a flat (counterclockwise).

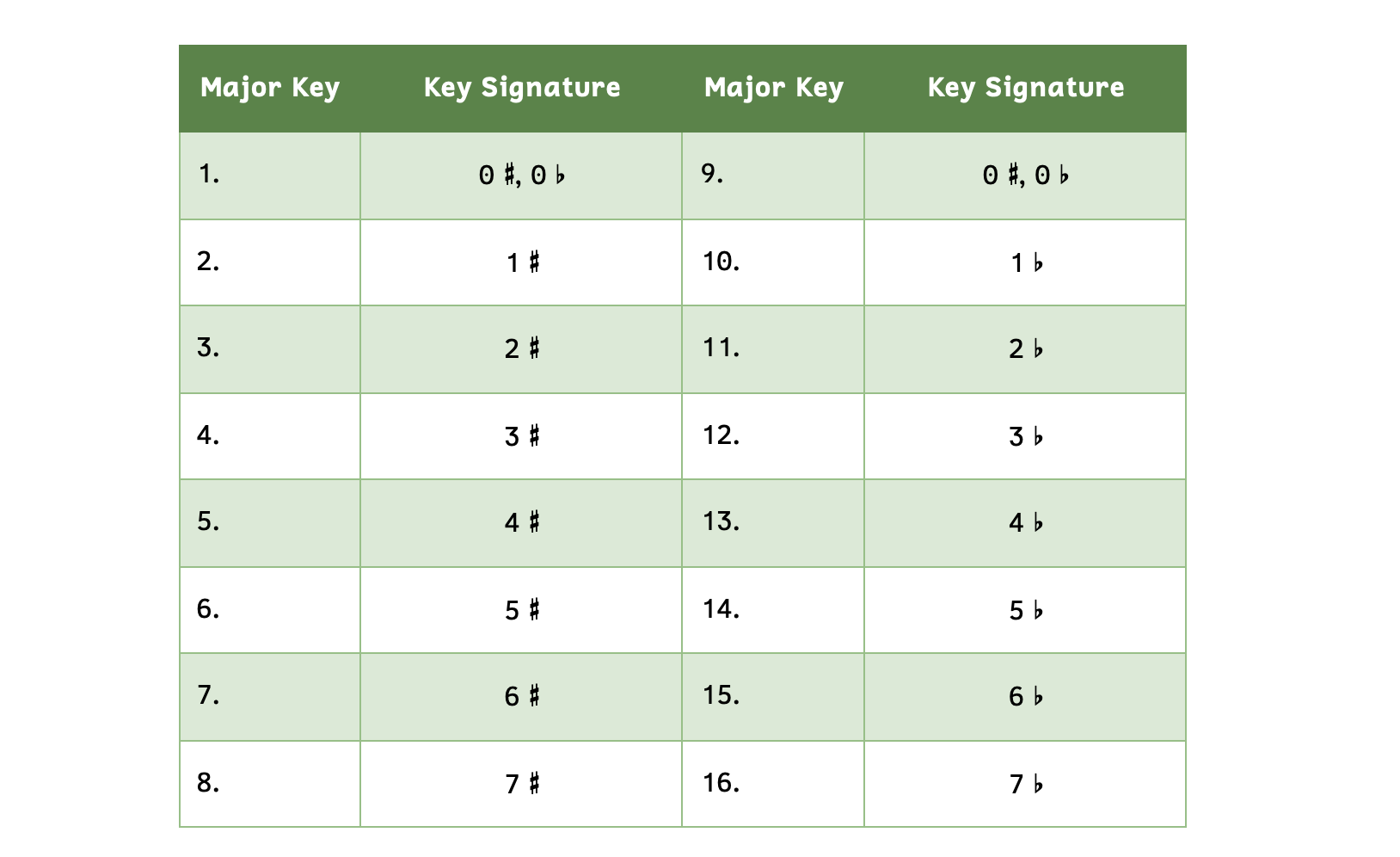

Practice 4.8

Directions:

- Using the circle of fifths, fill in the table. If you do not need the circle of fifths and already have the key signatures memorized, even better.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

2) G

3) D

4) A

5) E

6) B

7) F

8) C

9) C

10) F

11) B

12) E

13) A

14) D

15) G

16) C

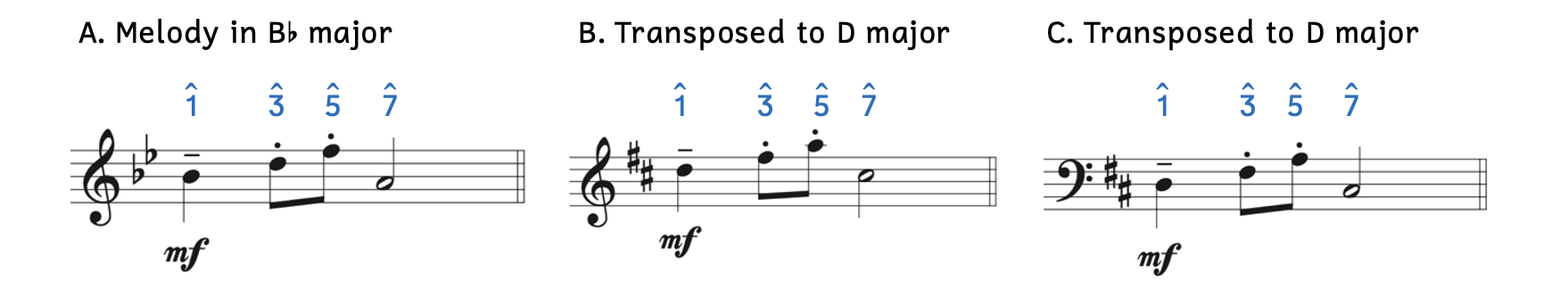

4.9 TRANSPOSITION: MELODIC

We already learned about rhythmic transposition when we rewrote a rhythm by the same proportion to fit in a different time signature. There is also melodic transposition, when you write or perform the same melody in a different key. Suppose you are playing the flute with a vocalist. The piece is in B![]() major, but the melody is too low for the singer. The vocalist is easily able to change keys using solfège, but for instrumentalists, it is not as easy unless you are fluent in key signatures. Since all major scales contain the same series of whole steps and half steps, you can easily transpose melodies by using scale degree numbers.

major, but the melody is too low for the singer. The vocalist is easily able to change keys using solfège, but for instrumentalists, it is not as easy unless you are fluent in key signatures. Since all major scales contain the same series of whole steps and half steps, you can easily transpose melodies by using scale degree numbers.

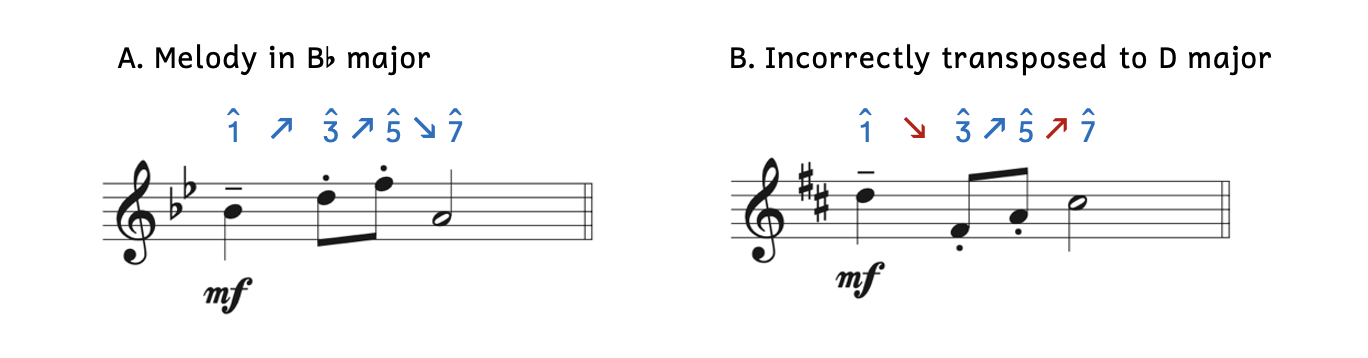

Example 4.9.1. Steps to melodic transposition

- Example 4.9.1A: First figure out the key the original melody is in and write scale degree numbers above.

- Example 4.9.1B: Transposing requires two steps.

- Write the clef and key signature of the new key. Rewrite the same scale degree numbers as the original melody above the blank staff.

- Write the correct pitches on the staff, making sure the rhythm, dynamics, and articulation marks are the same.

- Example 4.9.1C: You can transpose higher or lower. Here, the melody has been transposed over an octave lower and requires a change of clef.

- Notice that stem direction will change depending on placement on the staff.

An important thing to remember when transposing is that melodic contour matters. Melodic contour is the direction the melody ascends or descends. If the original melody leaps up from ![]() to

to ![]() , you cannot leap down. Listen to Examples 4.9.1A and B and how they sound the same. Now listen to Examples 4.9.2A and B.

, you cannot leap down. Listen to Examples 4.9.1A and B and how they sound the same. Now listen to Examples 4.9.2A and B.

Example 4.9.2. Incorrect transposition

The reason why Example 4.9.2B sounds so different is because the melodic contour is not correct (shown with red arrows).

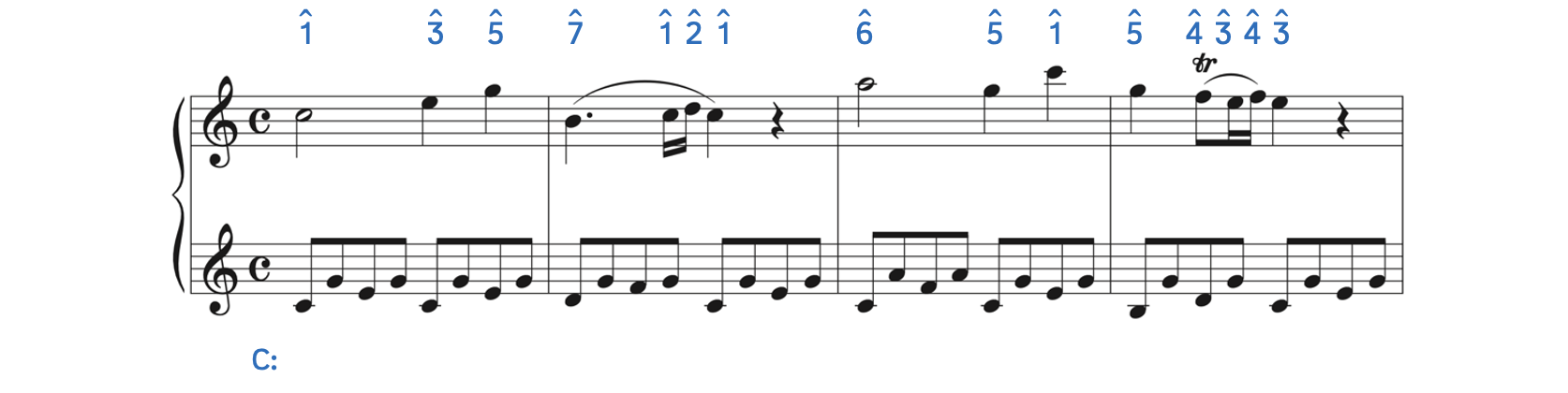

Composers will often repeat the same melody but in another key to give it variety. Example 4.9.3 illustrates the music from Example 4.9.1 in C major and F major.

Example 4.9.3. Melodic transposition: Mozart, Piano Sonata No. 16 in C Major, K. 545, i – Allegro

A. Original melody in C major

B. Transposed melody in F major

- Example 4.9.3.A:

- The original melody is in C major.

- Scale degree numbers are shown above the melody.

- Example 4.9.3B:

- The melody reappears at measure 42. However, this time it is in F major.

- Although the key signature does not change, there are two ways to see that this is no longer in C major.

- By writing the same scale degree numbers, you can see that

is now F.

is now F. - If you look at the music, every B has a flat. Therefore, even though the key signature does not have a flat, we know we are in F major because F major has one flat.

- By writing the same scale degree numbers, you can see that

Melodic Transposition

Melodic transposition is the act of rewriting music in a different key. Be sure to maintain the melodic contour, rhythm, articulation marks, and dynamics.

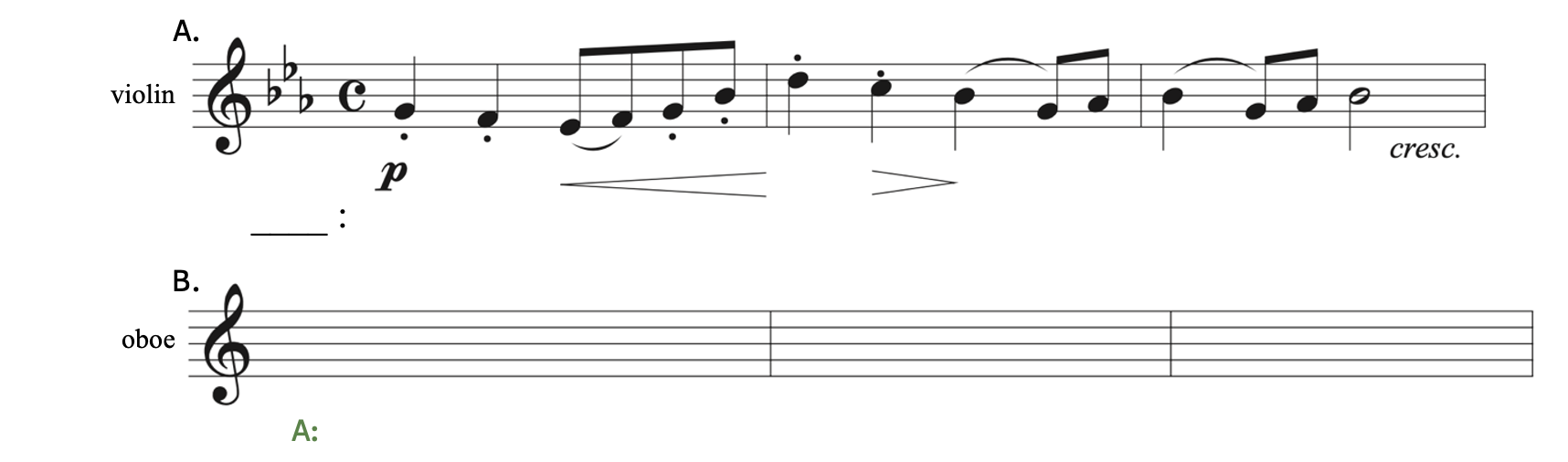

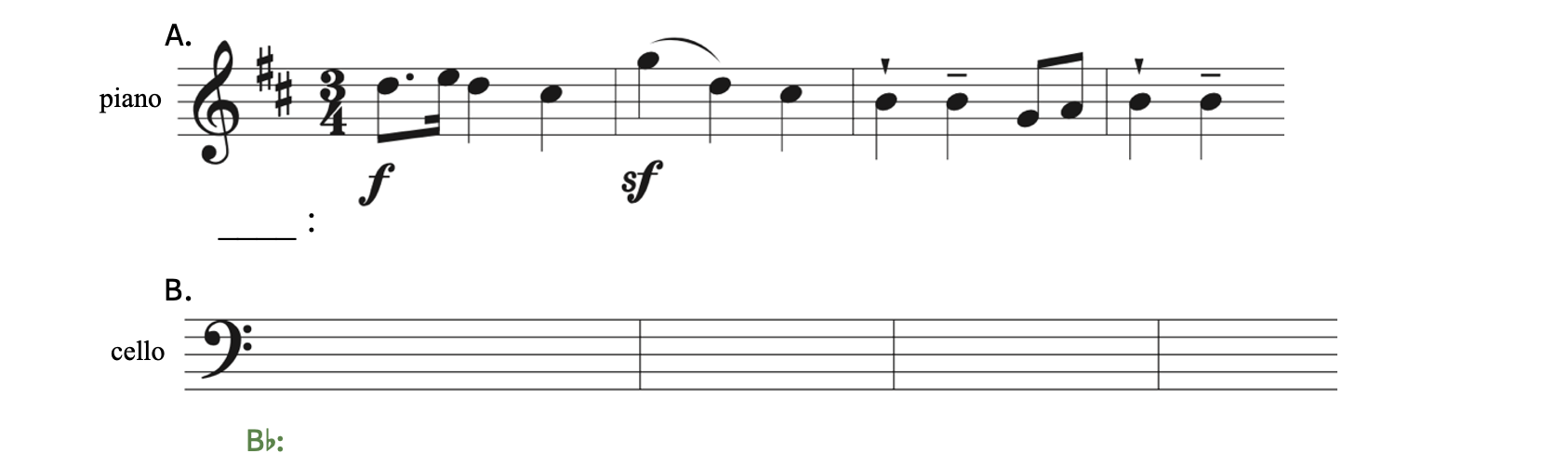

Practice 4.9

Directions:

- For A, write the key of the example, then write the scale degree numbers above the given melody.

- For B, write the key signature of the new key and add the same scale degree numbers above.

- Write the melody in the new key and add all appropriate musical symbols.

- Munktell[12], Violin Sonata, i – Allegro non tanto, vigoroso

2. Munktell, Violin Sonata, ii – Moderato energico

Click here to watch the tutorial.

SUMMARY

-

-

- A major tetrachord consists of three diatonic steps: whole – whole – half. [4.1]

- A major scale is made of two major tetrachords joined by a diatonic whole step: whole – whole – half :: whole :: whole – whole – half. [4.2, 4.3]

- Scale degree numbers are numbers with carets that represent members of the scale. Scale degree names also represent members of the scale. [4.4]

: tonic

: tonic : supertonic

: supertonic : mediant

: mediant : subdominant

: subdominant : dominant

: dominant : submediant

: submediant : leading tone

: leading tone

- The collection of flats or sharps in any major scale can be reduced to a key signature. Flats and sharps in key signatures are global, meaning they apply to notes in every octave. [4.5]

- The flats in major key signatures always go in this order: B

– E

– E – A

– A – D

– D – G

– G – C

– C – F

– F . [4.6]

. [4.6]

- The penultimate flat in the key signature is the key.

- The exception is F major, which has one flat.

- The sharps in major key signatures always go in this order: F

– C

– C – G

– G – D

– D – A

– A – E

– E – B

– B . [4.7]

. [4.7]

- The last sharp in the key signature is the leading tone of the key.

- The circle of fifths is a diagram that shows the relationship between keys. [4.8]

- Moving clockwise, the key ascends by five and adds a sharp.

- Moving counterclockwise, the key descends by five and adds a flat.

- Melodic transposition is the act of rewriting a melody in a different key. [4.9]

-

TERMS

-

-

- circle of fifths

- diatonic scale

- enharmonically equivalent keys

- key

- key signature

- major scale

- major tetrachord

- melodic contour

- melodic transposition

- mode

- scale degree names

- tonic (

)

) - supertonic (

)

) - mediant (

)

) - subdominant (

)

) - dominant (

)

) - submediant (

)

) - leading tone (

)

)

- tonic (

- scale degree number

- tetrachord

- tonal center

-

- Anne-Marie Krumpholtz (1766-1813) was a French composer and harpist. ↵

- Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was a French composer. ↵

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was a German composer. ↵

- Stephen C. Foster (1826-1864) was an American composer known as “The Father of American Music.” ↵

- In later chapters, we will use solfège periodically to clarify ambiguous scale degree numbers. ↵

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was an Austrian composer. ↵

- Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was a German composer. ↵

- Not all tempo markings are in Italian. Wagner chooses German for the tempo marking. Mässig bewegt means "moderately moving." ↵

- Hanriëtte Bosmans (1895-1952) was a Dutch composer and pianist. ↵

- Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831) was a Polish composer and pianist. ↵

- Example 4.7.4 includes an unfamiliar articulation marking: rf. Rinforzando, which comes from the Italian “reinforcing” or “strengthening,” is similar to sforzando but not as accented. ↵

- Helena Munktell (1852-1919) was a Swedish composer. ↵

Scale that uses every letter name once and only once.

Collection of four notes.

When notes are sounded one at a time.

Four notes with the pattern whole - whole - half.

Scale with the pattern WWHWWWH. Major keys are based on their major scales.

Arabic numeral with a caret above it that says which member of a scale a note is.

Names of members of a scale ( or names of scale degree numbers).

^1. This is considered the "home." Scales begin and end with tonic.

^2. "Above tonic."

^3. Halfway between tonic (^1) and dominant (^5).

^4. Five below tonic.

^5. Five above tonic.

^6. Halfway between the tonic descending to the subdominant.

^7. Diatonic half step below tonic and "leads" to tonic.

A note that tells us where "home" is; the music gravitates around the tonal center and does not feel complete unless we end at home.

Tells us the collection of pitches used based on a center pitch. The major mode and minor mode are the most common modes.

Mode that is often associated with happy music; based on the major scale.

Mode that is often associated with sad music; based on the natural minor scale.

Tonal center and mode combined, such as C major.

Group of flats or sharps located at the start of every system that says what the key may be.

Graphic representation of how all the major and minor keys are built by moving up or down by fifths. Each key either gains a sharp (clockwise) or gains a flat (counterclockwise).

Keys that share the same pattern of white and black keys on the piano, but are spelled differently (e.g., G-flat and F-sharp major).

Changing all pitches by the same proportion; when you write or perform the same melody in a different key.

The direction the melody ascends or descends.