6 Minor Scales and Keys

In Chapter 4, we learned about the major mode. In this chapter, we learn about the other mode most often used: the minor mode.

6.1 INTRODUCTION

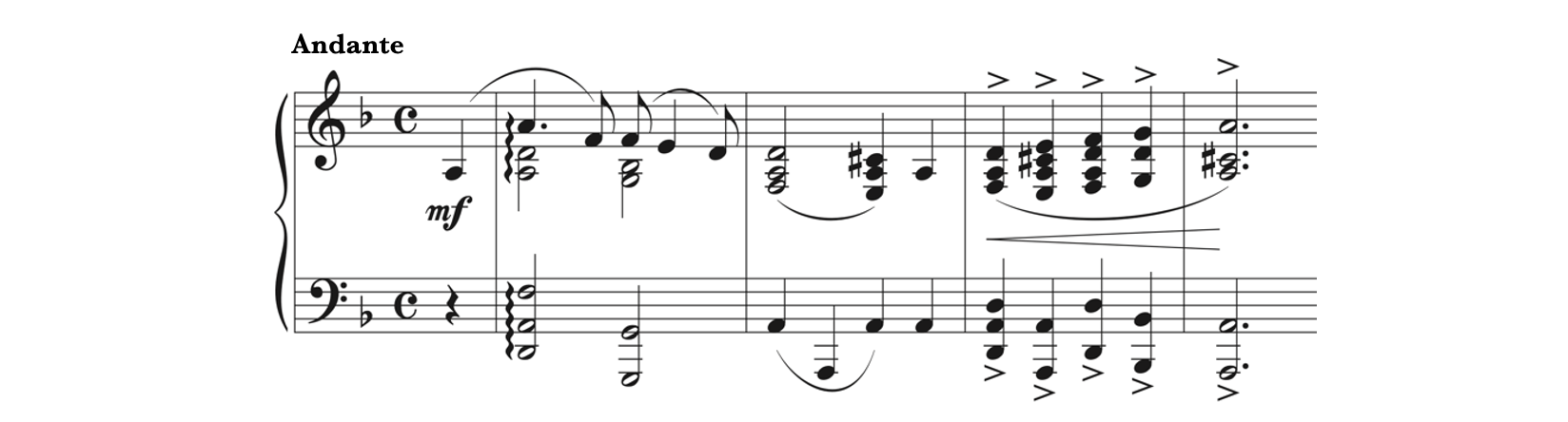

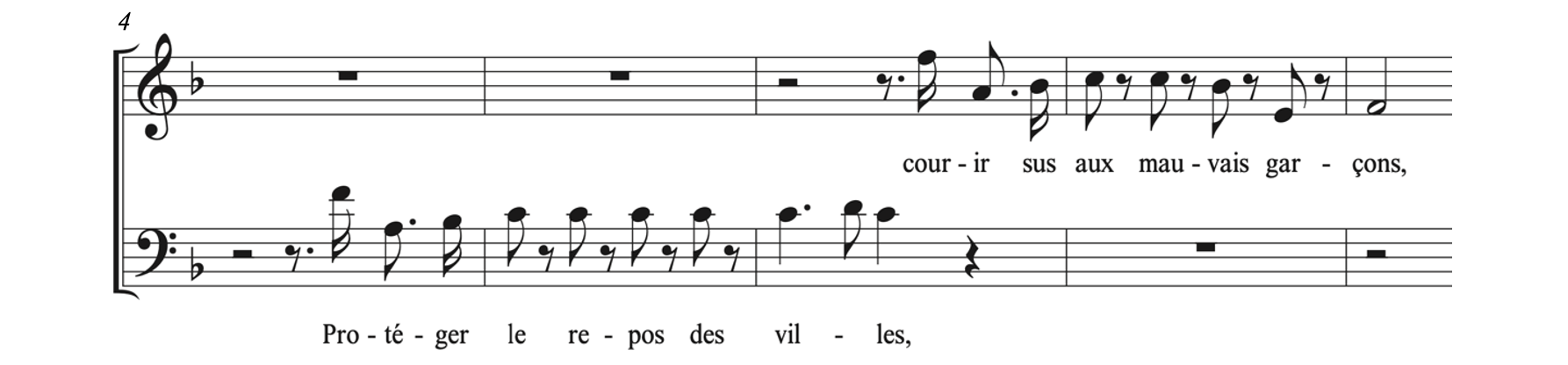

Listen to “Dingy, Dingy, Little Star” in Example 6.1.

Example 6.1. “Dingy, Dingy, Little Star”

What do you notice about “Dingy, Dingy, Little Star”? Aurally and visually, how does it compare to “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star?”

- “Dingy, Dingy” sounds gloomy.

- Although the tonal center appears to be C, there are two flats. C major has no sharps or flats.

The fact that the music sounds gloomy and its tonal center does not match its major key signature tells us that this example is in the minor mode. Like the major mode, the minor mode has a distinct collection of pitches that revolve around a tonal center. Unlike the major mode, the pattern of steps that make up the collection is different.

6.2 NATURAL MINOR SCALE

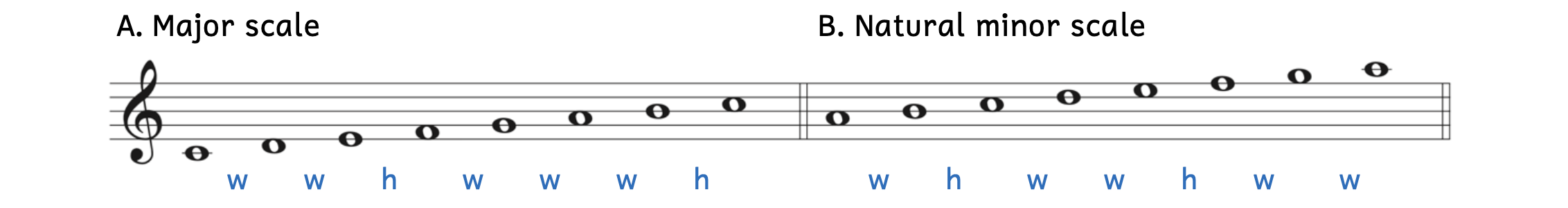

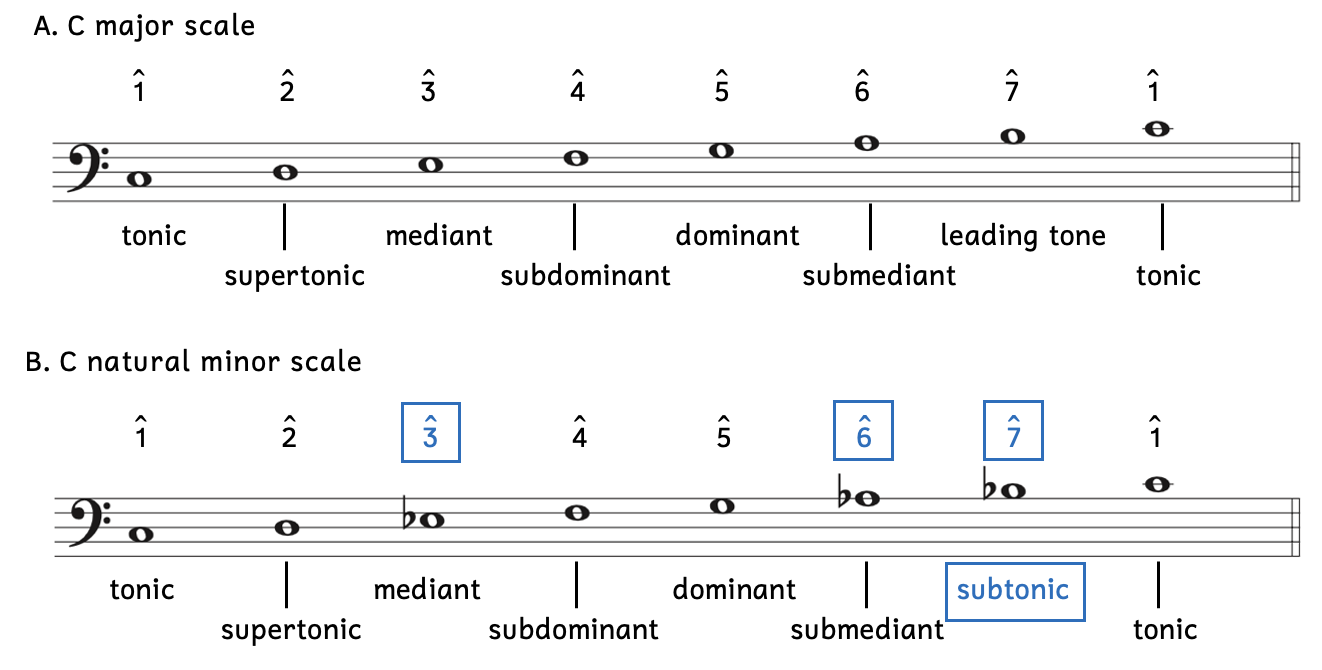

The minor mode is based on the natural minor scale which uses a completely different pattern than the major scale.

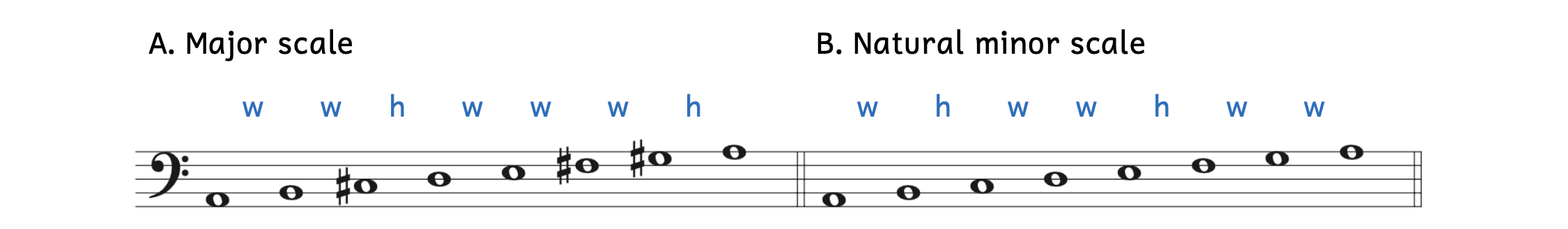

- Major scale: whole – whole – half – whole – whole – whole – half

- Natural minor scale: whole – half – whole – whole – half – whole – whole

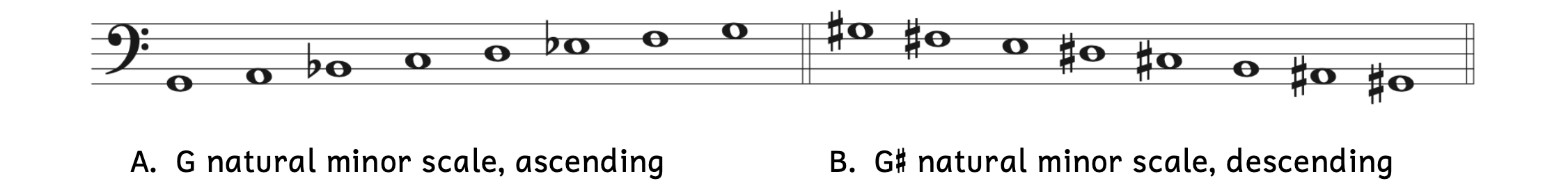

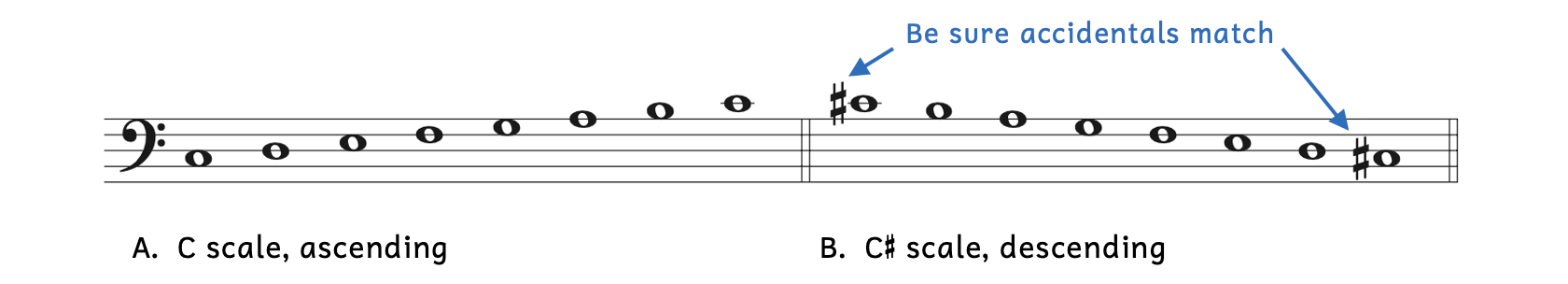

Example 6.2.1. Scales

Because the pattern is different, the natural minor scale has its own distinct sound. Notice that the scale is called the “natural minor scale,” and not simply the “minor scale.” This is because there are three different types of minor scales. We will learn about the other two later in this chapter.

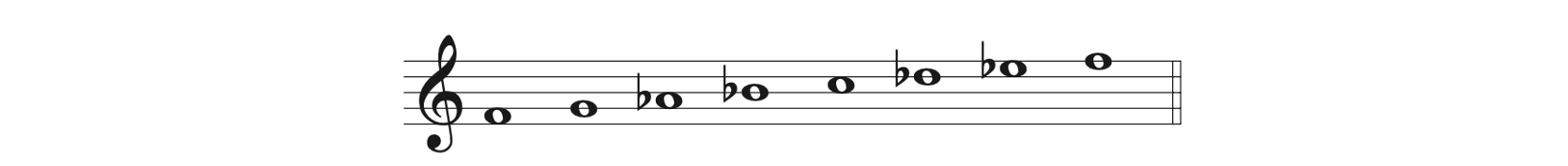

You will be asked to write (and perform) ascending and descending natural minor scales. The directions are the same for ascending and descending scales.

Steps to Writing a Natural Minor Scale

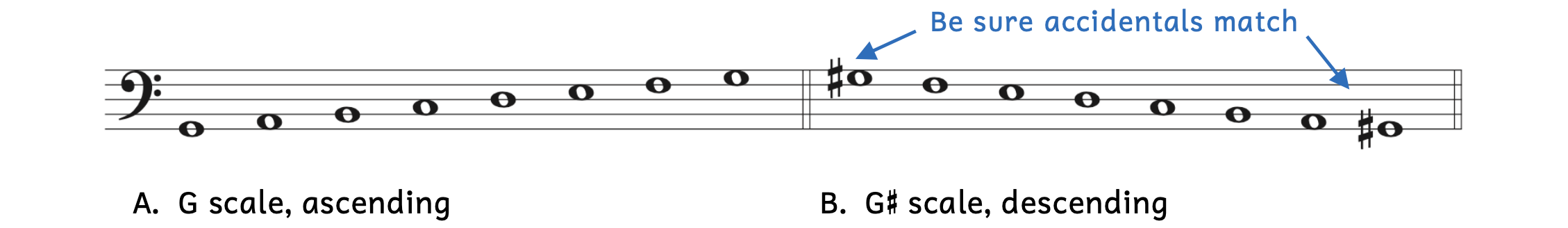

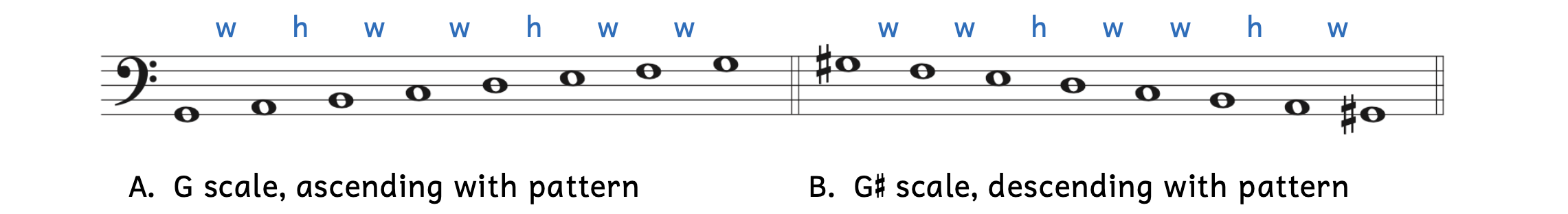

Step one: Write in all the notes diatonically. That is, write each note once and only once in ascending or descending order (alternate line–space or space–line). Do not skip any notes, and be sure that the first and last notes are the same notes with the same accidentals.

Example 6.2.2. Step one

Step two: Write in the pattern of whole steps and half steps. Do not forget that for descending natural minor scales, the pattern must go in reverse order.

Example 6.2.3. Step two

Step three: Add accidentals. Natural minor scales will only contain sharps or flats—never both.

Example 6.2.4. Step three

Writing Natural Minor Scales

- Write in all the note names diatonically (once and only once) in ascending or descending order.

- Write in the pattern of whole steps and half steps: whwwhww.

- Add accidentals. Natural minor scales will only contain sharps or flats–never both.

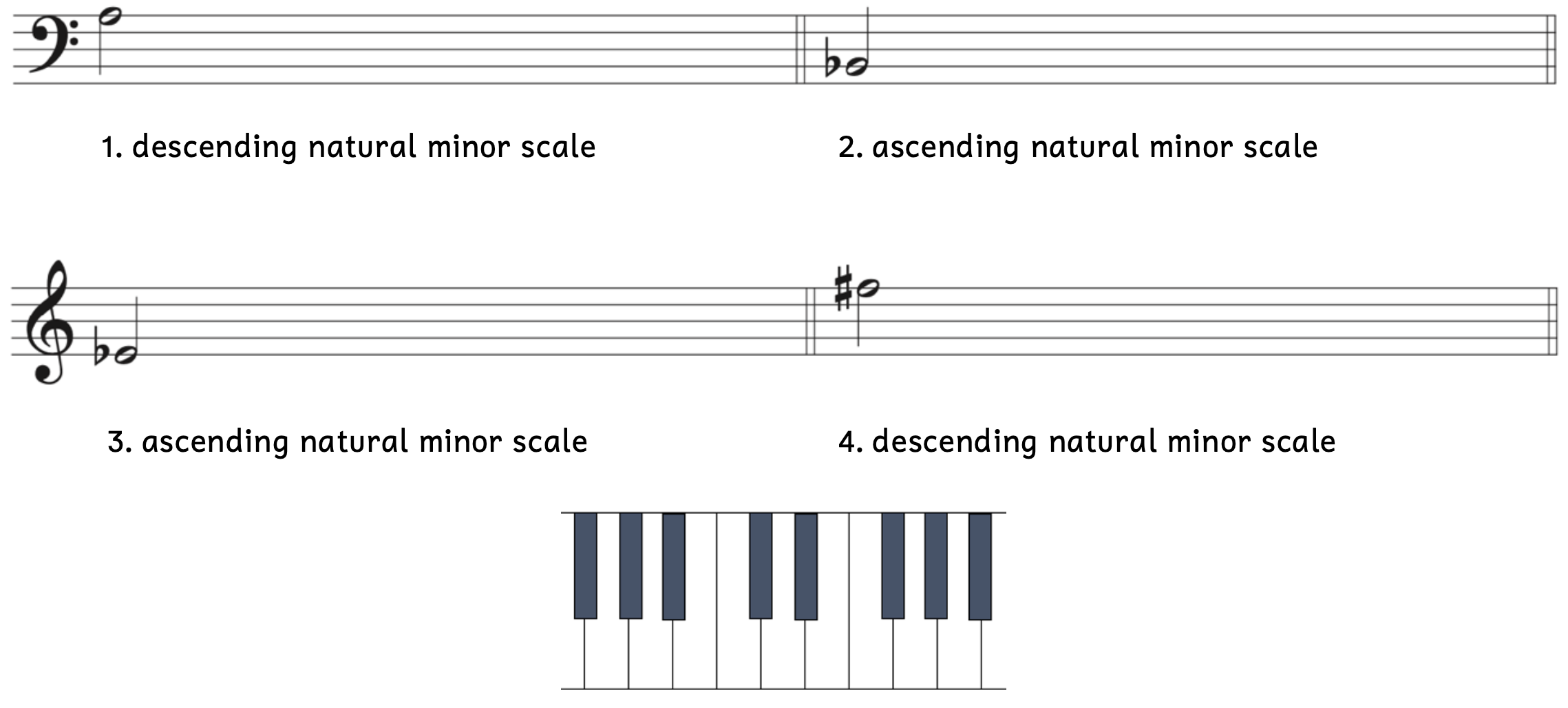

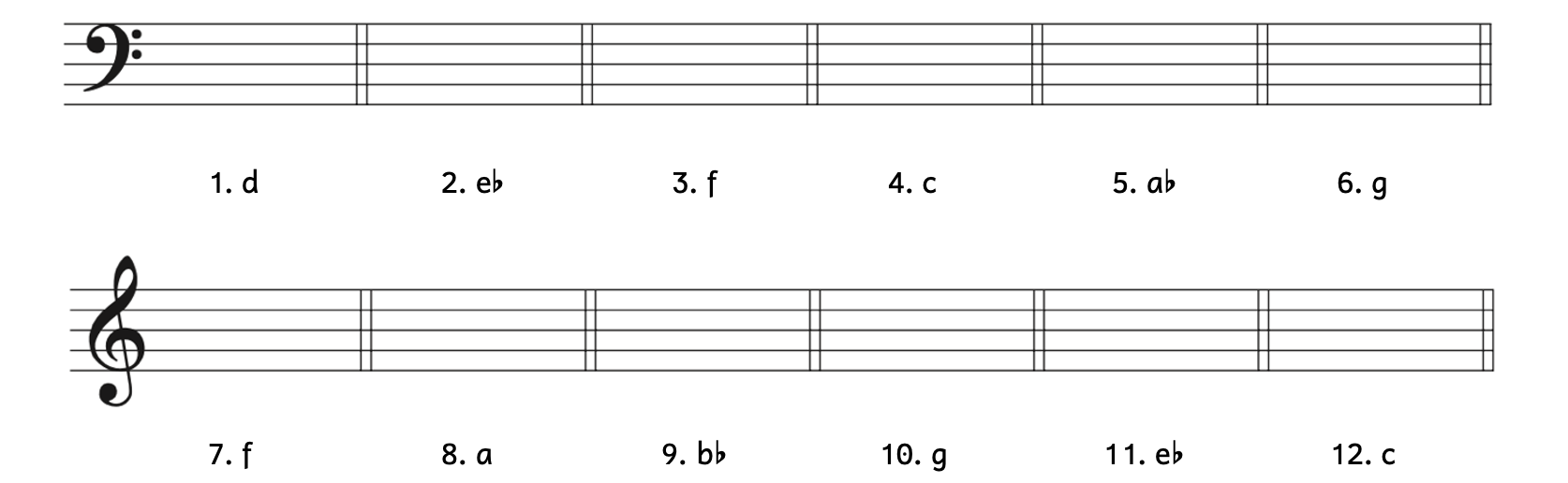

Practice 6.2. Building Natural Minor Scales by Step Pattern

Directions:

- Construct the following natural minor scales on the staff using half notes. Be aware of stem direction.

- First write in all the pitches diatonically so you do not repeat or skip any note names. Then add accidentals.

- If it helps, write in “w” for whole steps and “h” for half steps.

- You may use the keyboard below for help.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

6.3 MINOR KEYS

A natural minor scale is not only an organized way to write notes in alphabetical order. Just as the major scale, the natural minor scale is an organized way of telling us the contents of a musical key, which combines the tonal center and mode. We learned the following from Chapter 4:

- The tonic is the tonal center.

- The mode tells us the collection of pitches used based on a tonal center. The most common modes are the major mode and minor mode.

- The key combines the tonal center and the mode.

We can figure out the minor key by its natural minor scale.

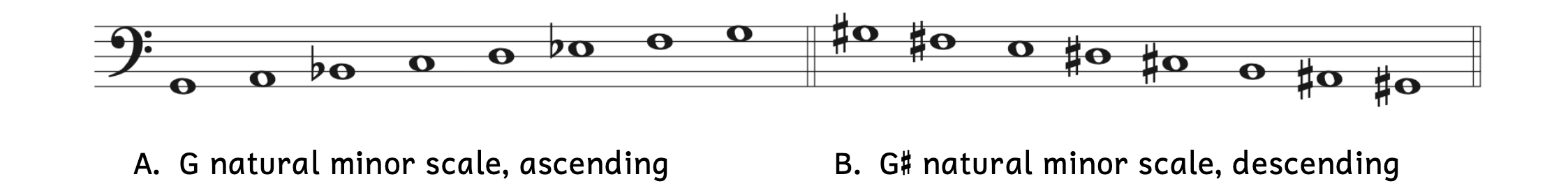

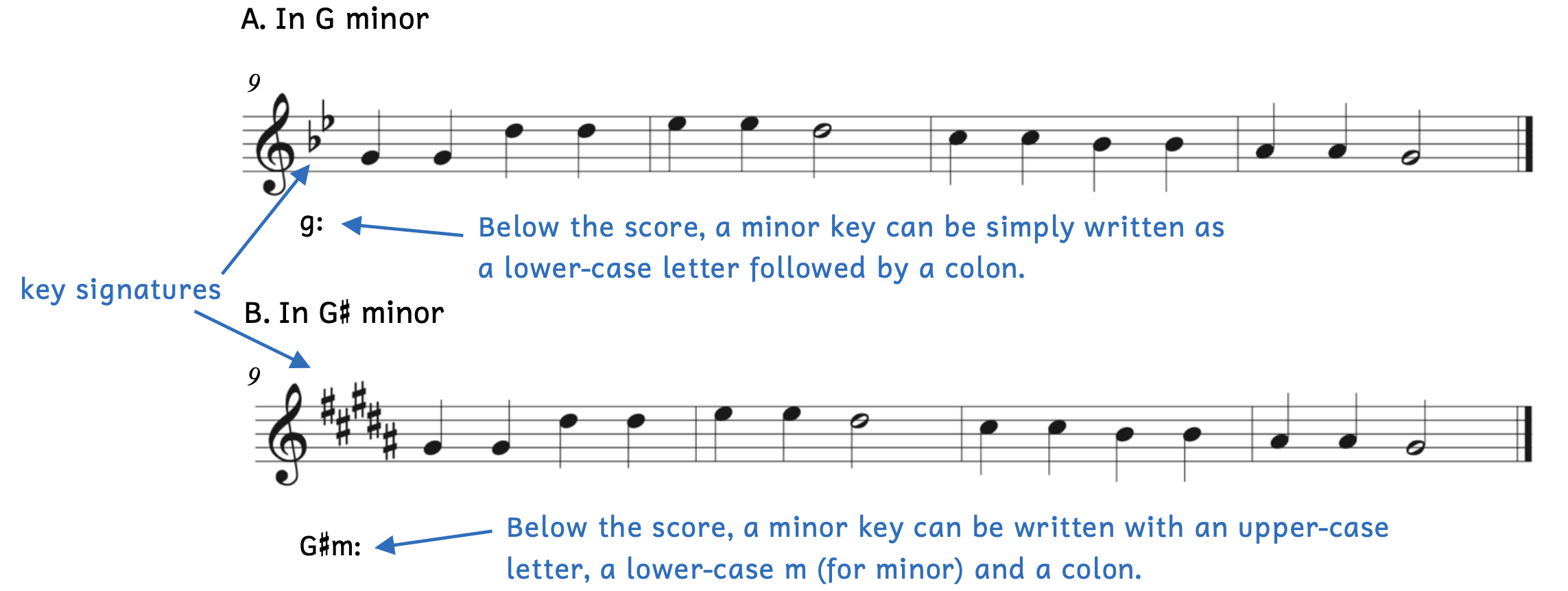

Example 6.3.1. Natural minor scales

The pitch collection combined with the tonal center tells us the key.

- Example 6.3.1A: If we have a piece of music that centers around G with two flats, it is in the key of G minor. This is because the G natural minor scale has two flats.

- Example 6.3.1B: If we have a piece of music that centers around G

with five sharps, it is in the key of G

with five sharps, it is in the key of G minor. This is because the G

minor. This is because the G natural minor scale has five sharps.

natural minor scale has five sharps.

- Although there are six sharps in Example 6.3.1B, there are only five different sharps.

Ideally, you will be able to hear a musical example and tell if it is in major or minor. Example 6.3.2 and 6.3.3 are two famous classical works that are in minor keys.

Example 6.3.2. Minor key: Tchaikovsky[1], Swan Lake, Act I, No. 9, Finale

Example 6.3.3. Minor key: Bizet[2], L’Arlésienne Suite No. 1, I. Overture

Can you hear that the music in Examples 6.3.2 and 6.3.3 are in minor (i.e., are “sad”)? Even though one is slow and quiet while the other is fast and loud, they are both in minor. If you are not able to identify that they are in minor yet, do not fret. Understanding, writing, and hearing music all take time and practice. We will also learn how you can recognize if a piece is in minor without listening to it.

Just as in major, rather than constantly writing and rewriting accidentals within the score, musicians use key signatures to simplify writing (and reading) music in minor keys. A key signature is the group of flats or sharps located at the start of every system of music. Also like in major, we can figure out a minor key by its corresponding scale. The following examples show “Dingy, Dingy, Little Star” written with minor key signatures.

Example 6.3.4. “Dingy, Dingy, Little Star” with key signatures

The key signature tells us which notes always have accidentals. For musicians, seeing the key signature once at the beginning is much easier than reading numerous accidentals. Just as in major, accidentals in minor key signatures are globalized.

- Example 6.3.4A: At first glance, one may think the example is in B

major.

major.

- However, when we listen to the example, it sounds gloomy.

- The final double bar line tells us that the piece ends on G. When we write out the collection of pitches beginning and ending on G, we know that we are in G minor and not B

major.

major. - Below the staff, write the minor key with a lower-case letter (see Example 6.3.4A)

- Example 6.3.4B: Notice that the letters of the note names are the same in Examples 6.3.4A and B. However, because of the key signature, Example 6.3.4B is in G

minor, and not G minor.

minor, and not G minor.

- Below the staff, you can also write the key with an upper-case letter followed by a lower-case m (see Example 6.3.4B).

When writing sentences, always write out the word “minor” and capitalize the name of the key: G minor, not g minor.

Minor Keys

Minor keys share the same accidentals as the natural minor scale.

6.4 MINOR KEY SIGNATURES WITH FLATS

Like major key signatures, accidentals in minor key signatures must appear in a specific order and they must be placed on specific locations within the staff. Oftentimes, students will memorize major key signatures but not minor key signatures, which creates a disadvantage. If you are able to quickly identify and write all the major and minor key signatures, music theory will be much easier for you.

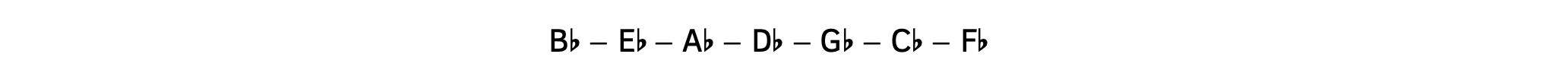

Key signatures will have either flats or sharps, not both. We will begin with minor key signatures with flats. Flats in minor key signatures always appear in the same order as they did in major:

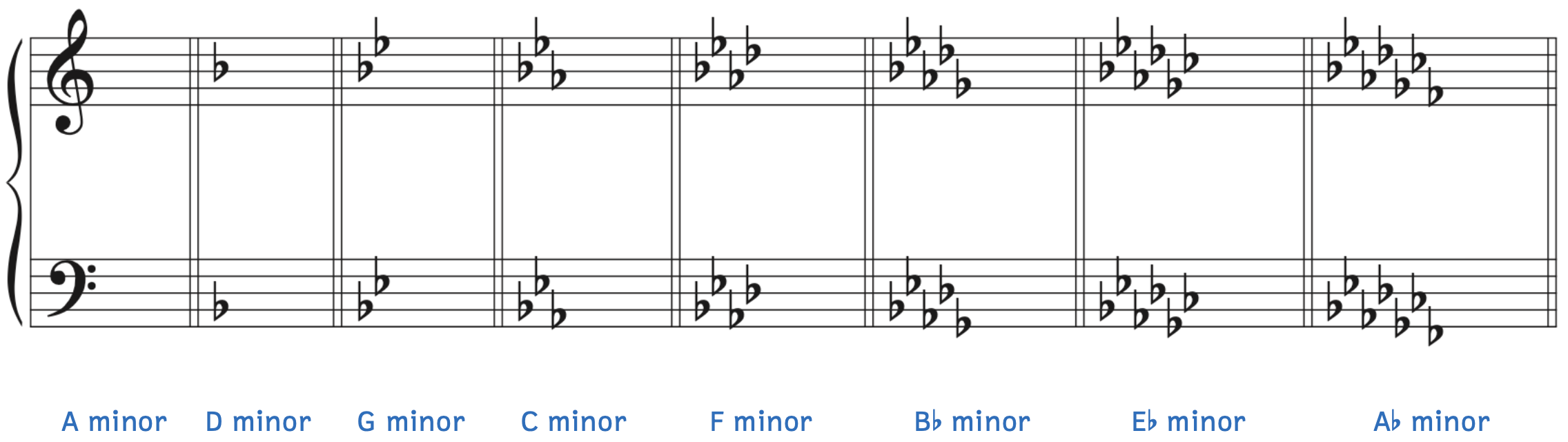

Fortunately, the placement of the flats in a key signature is exactly the same in major and minor. Since there are seven different note names, there can be a maximum of seven flats in a key signature. The example below shows all the minor key signatures with flats.

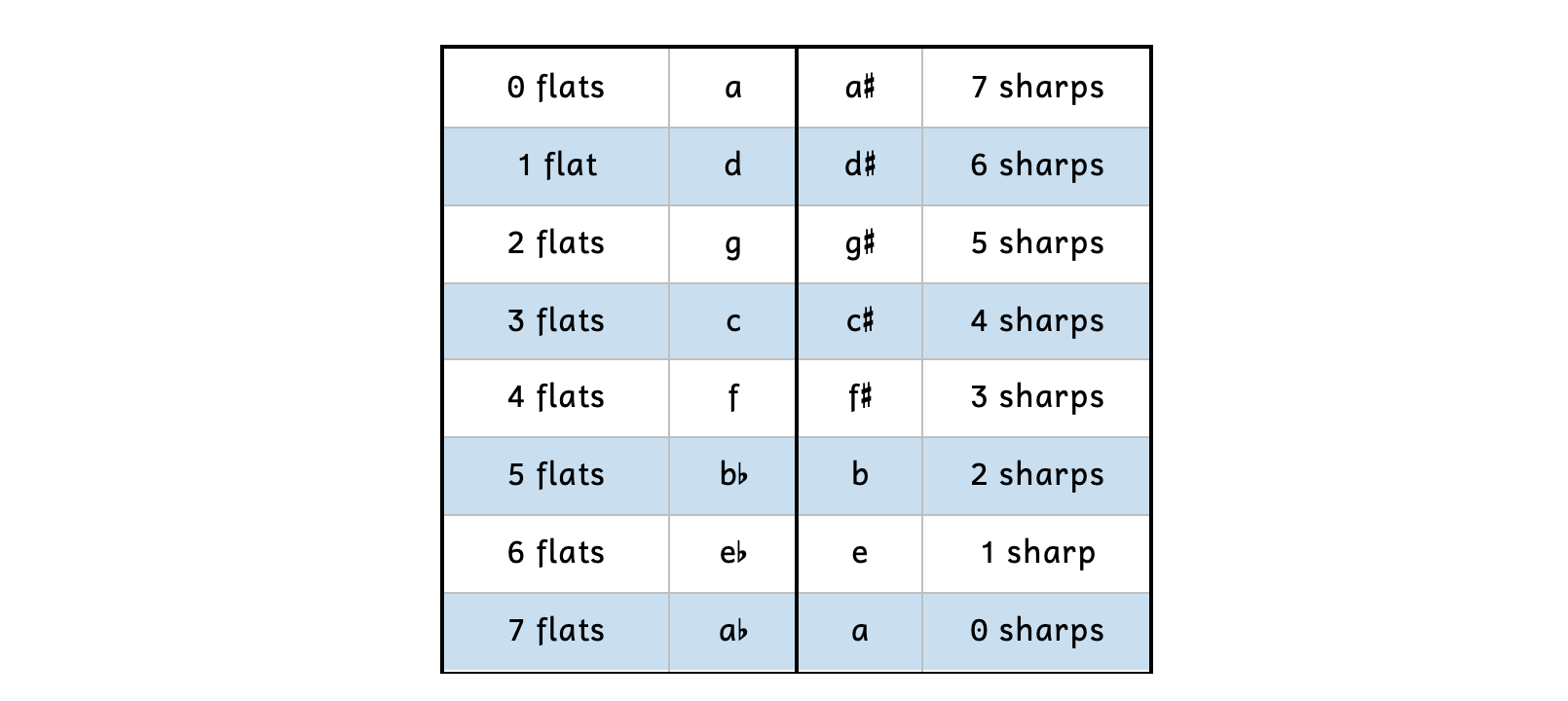

Example 6.4.1. Minor key signatures from zero to seven flats

Notice that A minor has zero flats while A![]() minor has seven flats. While we could look at the penultimate flat for major keys with flats, there is no easy shortcut for minor keys with flats.

minor has seven flats. While we could look at the penultimate flat for major keys with flats, there is no easy shortcut for minor keys with flats.

Now we will put together everything we have learned to figure out the key of a musical example in minor.

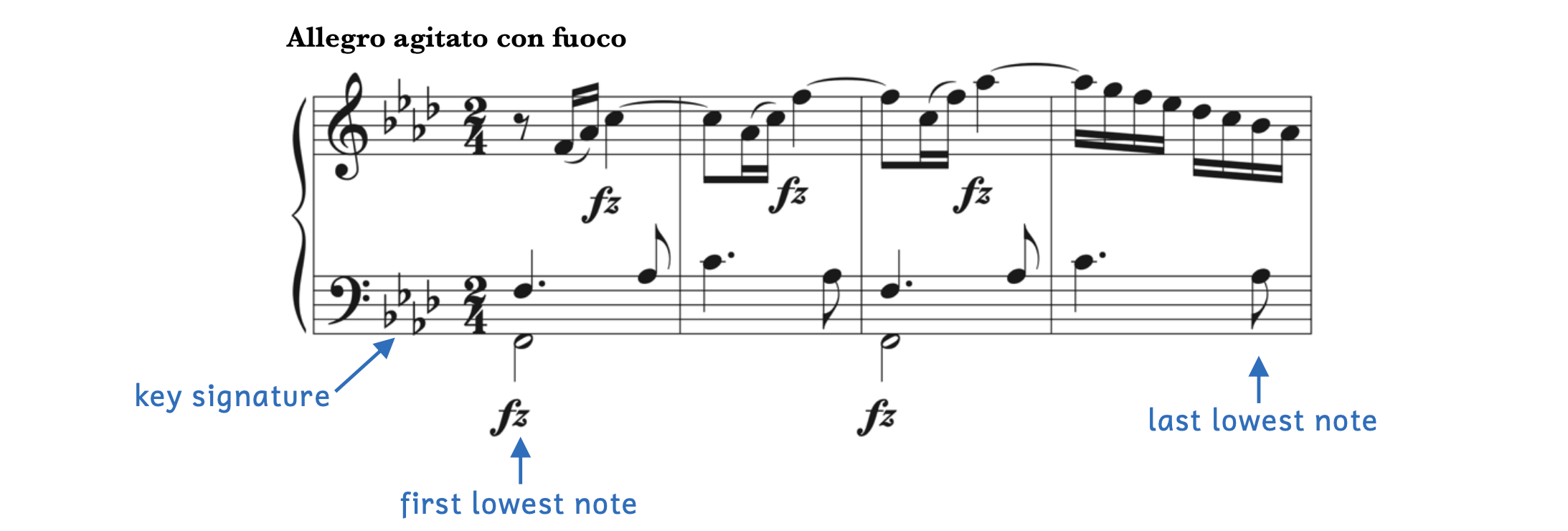

Example 6.4.2. Finding the key: Montgeroult[3], Piano Sonata, Op. 5, No. 2, iii – Allegro agitato con fuoco

When figuring out the key of a given musical example, follow these steps:

- Listen to the example: Does it sounds like it’s in major (happy) or minor (sad)?

- Example 6.4.2 sounds like it is in minor. Although “angry” may be a better description than “sad,” this example does not sound happy.

- Look at the key signature.

- The key signature has four flats, which is the key of F minor.

- Look at the first lowest note.

- The first lowest note is F.

- Look at the last lowest note.

- The last lowest note is A

.

.

- The last lowest note is A

The first three steps point to F minor. In this case, using the last lowest note was not reliable. However, since three of the four steps led to F minor, the key is F minor. The steps are more dependable when used in combination.

Relative Keys

In Example 6.4.2, the last lowest note was A![]() . If we look at the key signature, we see that the two options for key signatures with four flats are F minor and A

. If we look at the key signature, we see that the two options for key signatures with four flats are F minor and A![]() major. Fortunately, the music sounds like it is in minor and the first lowest note is F, so we know the excerpt is in F minor.

major. Fortunately, the music sounds like it is in minor and the first lowest note is F, so we know the excerpt is in F minor.

When a major key signature and minor key signature are the same, such as A![]() major and F minor, that major key and minor key are relative keys.

major and F minor, that major key and minor key are relative keys.

- A

major is the relative major of F minor because both keys have four flats.

major is the relative major of F minor because both keys have four flats. - F minor is the relative minor of A

major because both keys have four flats.

major because both keys have four flats.

There are two similar methods to find the relative key. The first involves counting diatonic steps.

Counting Diatonic Steps to Find the Relative Key

Let’s find the relative major of E![]() minor.

minor.

- Count up three diatonic steps (i.e., letter names). Do not worry about accidentals for the first step. Simply count up three letter names.

- E

< F < G

< F < G

- E

- Match the accidentals to figure out the relative major. Is the relative major G major, G

major, or G

major, or G major?

major?

- G major: Not possible, because G major is a key with sharps, and E

minor has flats.

minor has flats. - G

major: Yes

major: Yes - G

major: Impossible, because there is no such key as G

major: Impossible, because there is no such key as G major.

major.

- G major: Not possible, because G major is a key with sharps, and E

- Therefore, the relative major of E

minor is G

minor is G major. Both keys have six flats.

major. Both keys have six flats.

Let’s try one going the other way: Find the relative minor of E![]() major.

major.

- Count down three diatonic steps (i.e., letter names). Do not worry about accidentals for the first step. Simply count down three letter names.

- E

> D > C

> D > C

- E

- Match the accidentals to figure out the relative minor. Is the relative major C minor, C

minor, or C

minor, or C minor?

minor?

- C minor: Yes

- C

minor: Impossible, because there is no such key as C

minor: Impossible, because there is no such key as C minor.

minor. - C

minor: Not possible, because C

minor: Not possible, because C minor has sharps and E

minor has sharps and E major has flats.

major has flats.

- Therefore, the relative minor of E

major is C minor. Both keys have three flats.

major is C minor. Both keys have three flats.

Another method involves counting half steps.[4]

Counting Half Steps to Find the Relative Key

Let’s find the relative major of F minor.

- Count up three half steps.

- F < F

< G < G

< G < G /A

/A

- F < F

- There are two options: G

or A

or A . Choose the key that shares the same accidentals.

. Choose the key that shares the same accidentals.

- G

major: Impossible, because there is no such key as G

major: Impossible, because there is no such key as G major.

major. - A

major: Yes.

major: Yes.

- G

- Therefore, the relative major of F minor is A

major. Both keys have four flats.

major. Both keys have four flats.

To find the relative minor of a given major key, follow the same steps but count down three half steps instead of up three half steps.

Let’s find the relative minor of D![]() major.

major.

- Count down three half steps.

- D

> C > B > A

> C > B > A /B

/B

- D

- There are two options: A

or B

or B . Choose the key that shares the same accidentals.

. Choose the key that shares the same accidentals.

- A

minor: Not possible, because A

minor: Not possible, because A minor has sharps and D

minor has sharps and D major has flats.

major has flats. - B

minor: Yes.

minor: Yes.

- A

- Therefore, the relative major of D

major is B

major is B minor. Both keys have five flats.

minor. Both keys have five flats.

Although it is important to know relative keys, you should ultimately memorize the fifteen minor keys as you did with the fifteen major keys.

Relative Keys

There are two methods for finding relative keys.

- Counting diatonic steps:

- To find the relative major, count up three diatonic steps (i.e., letter names) and select the key with the same accidentals.

- To find the relative minor, count down three diatonic steps (i.e., letter names) and select the key with the same accidentals.

- Counting half steps: This is the same method, but count three half steps instead of three diatonic steps.

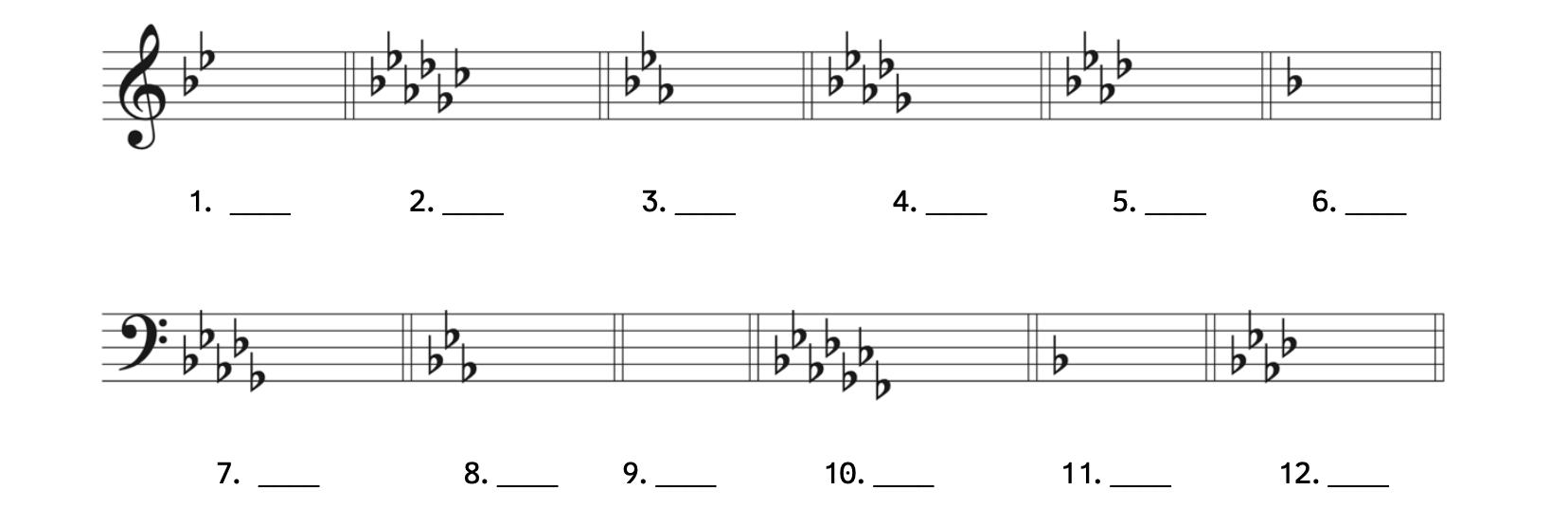

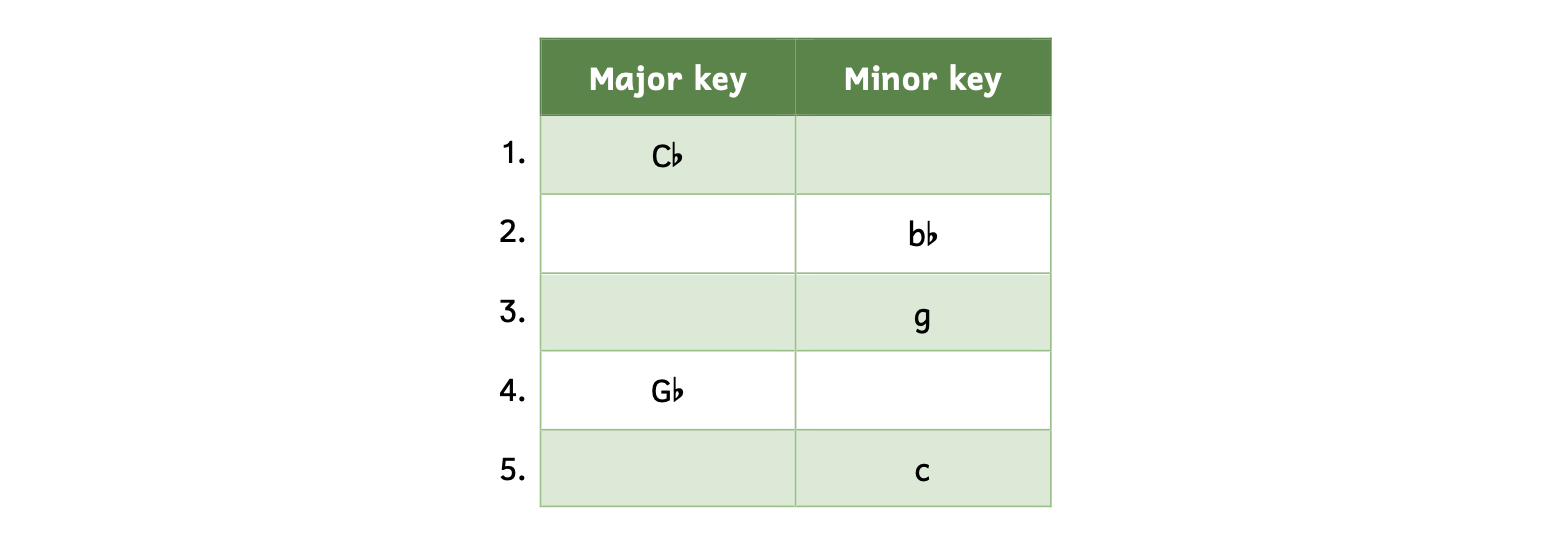

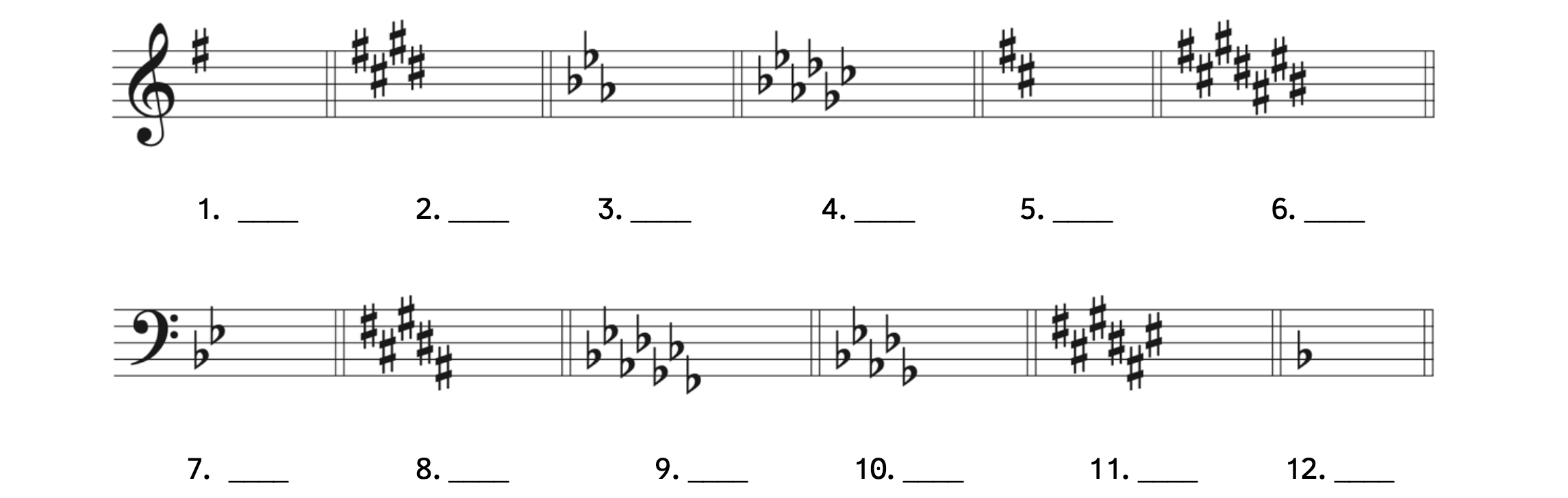

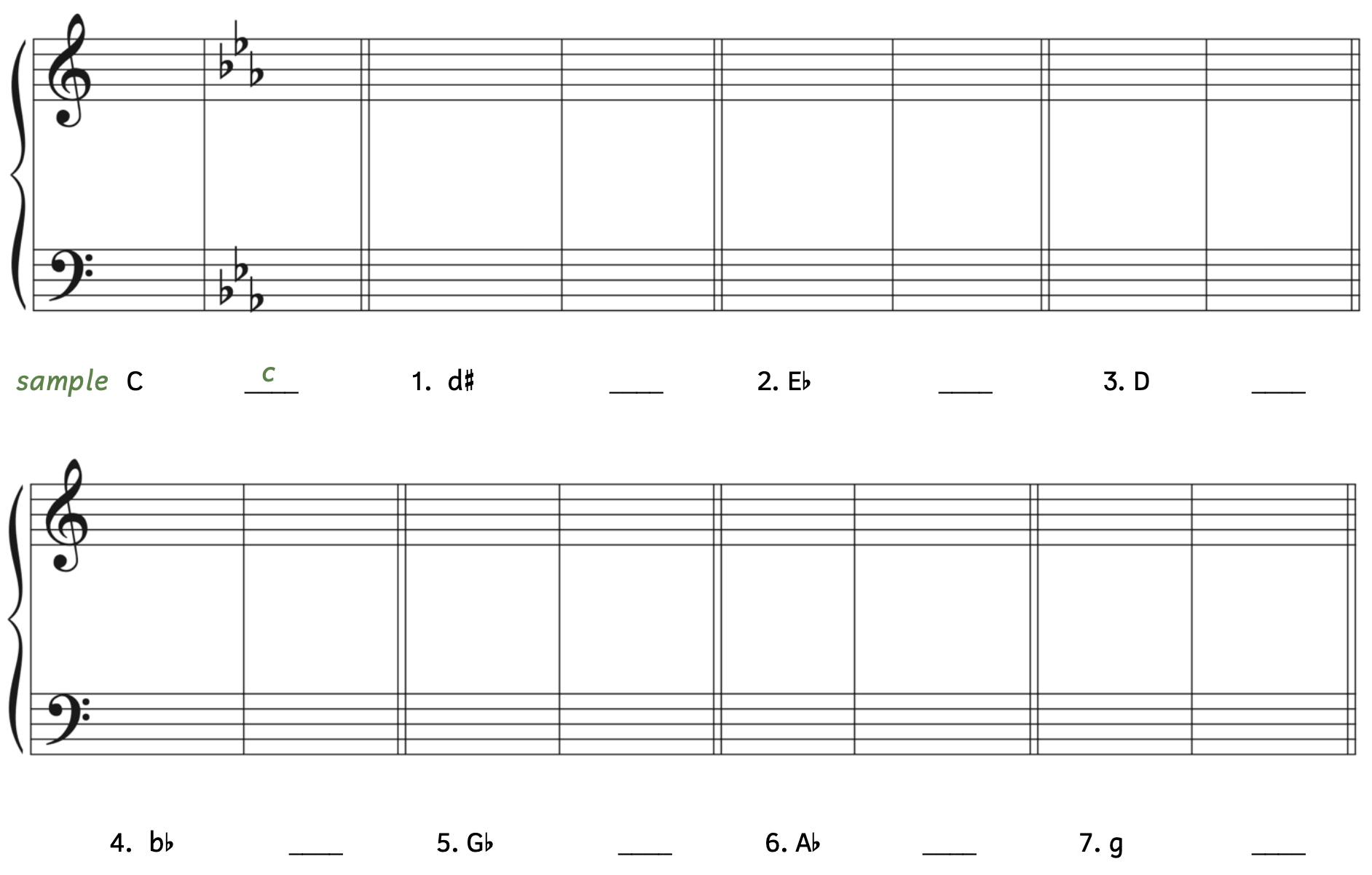

Practice 6.4A. Identifying Minor Key Signatures with Flats

Directions:

- Identify the minor keys. For minor keys, you only need to write a lowercase letter (e.g., d).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

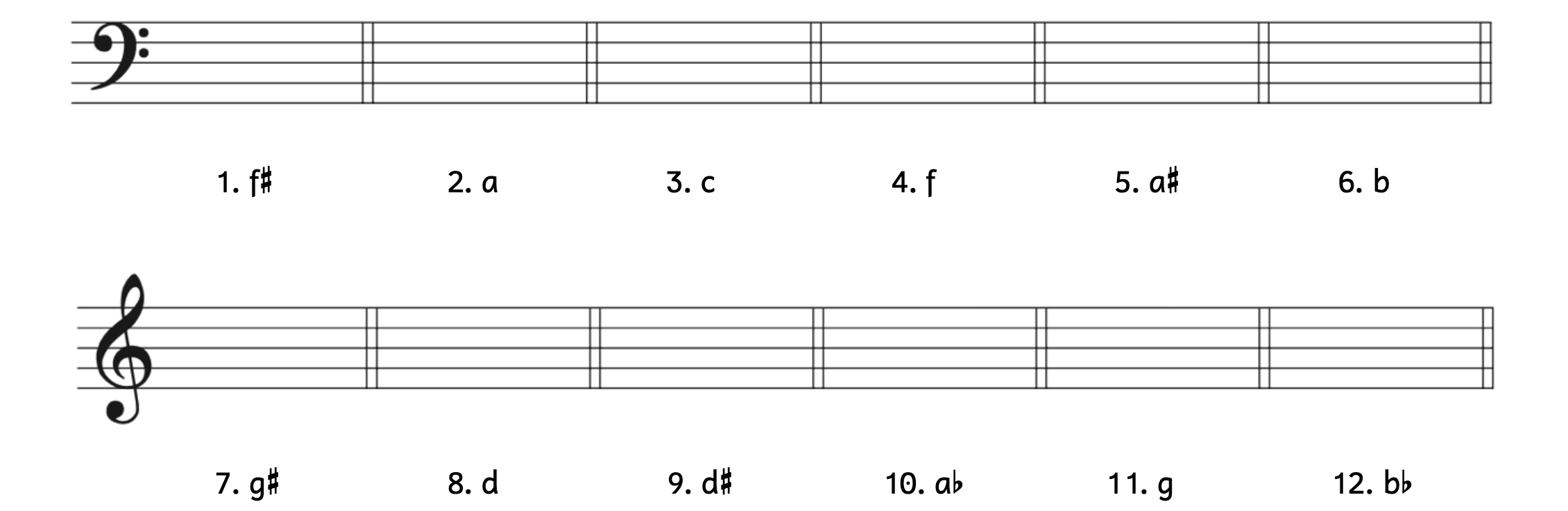

Practice 6.4B. Writing Minor Key Signatures with Flats

Directions:

- Write the given key signatures on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

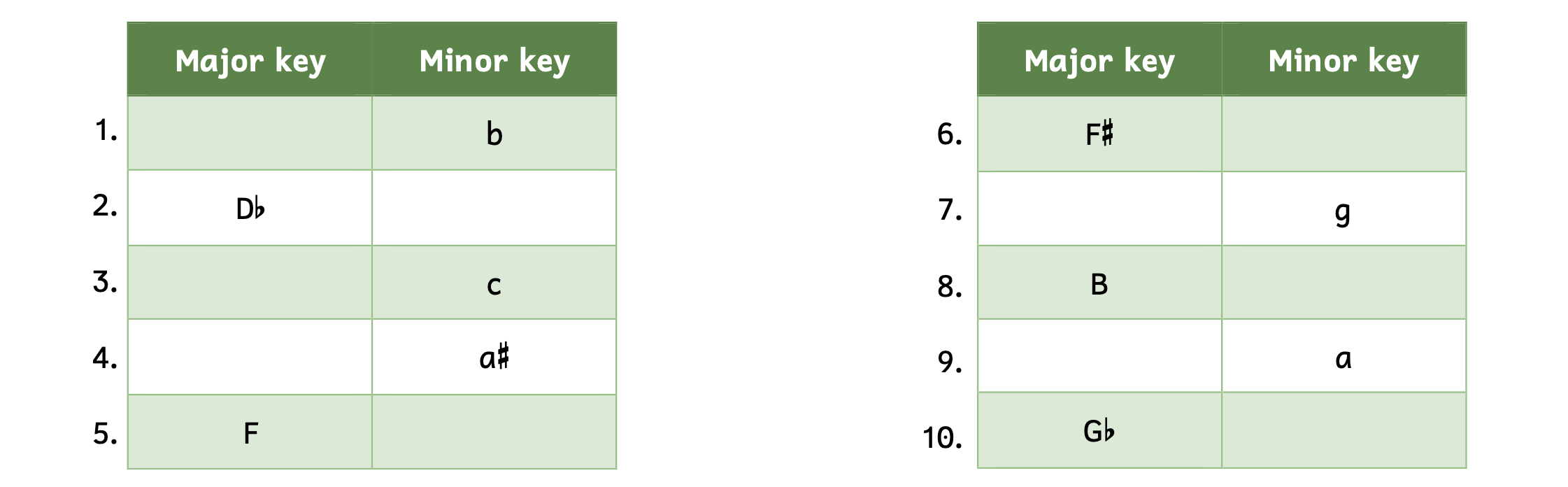

Practice 6.4C. Identifying Relative Keys with Flats

Directions:

- Write the relative major or minor key in the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

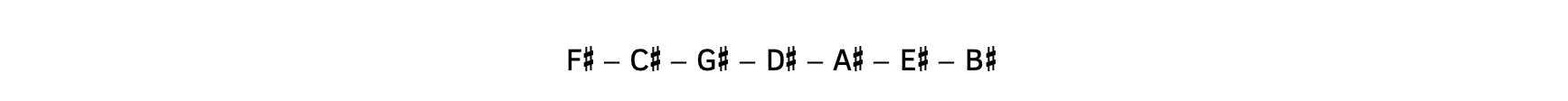

6.5 MINOR KEY SIGNATURES WITH SHARPS

Just as sharps in major key signatures, sharps in minor key signatures always appear in this order:

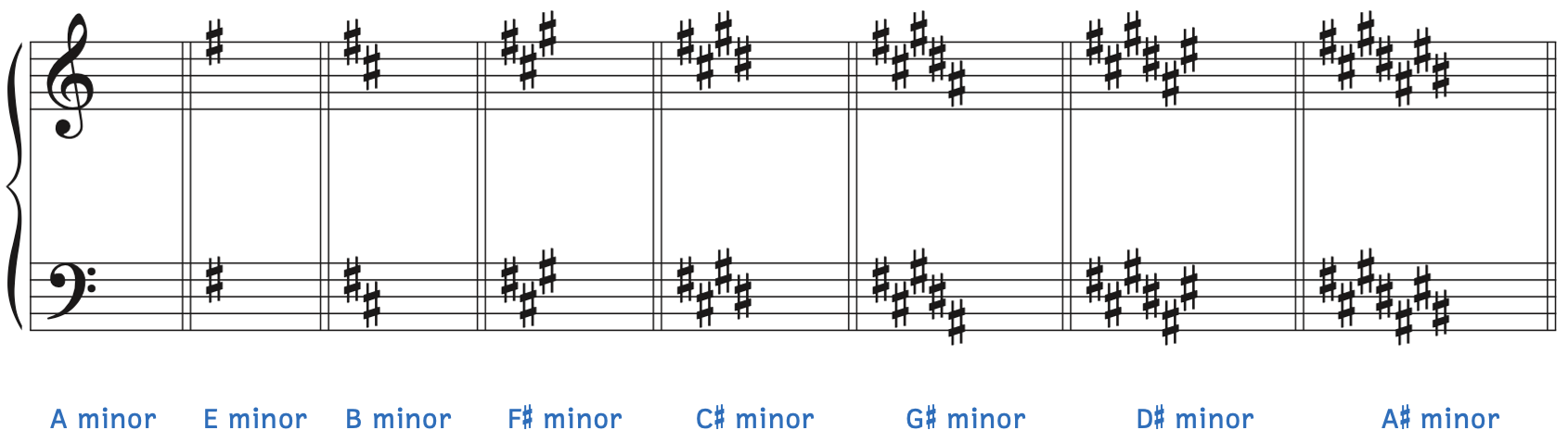

Fortunately, the placement of the sharps in a key signature is exactly the same in major and minor. Since there are seven different note names, there can be a maximum of seven sharps in a key signature. The example below shows all the minor key signatures with sharps.

Example 6.5.1. Minor key signatures from zero to seven sharps

Notice that A minor has zero sharps while A![]() minor has seven sharps. As we did with minor keys with flats, it is handy to be able to figure out relative keys.

minor has seven sharps. As we did with minor keys with flats, it is handy to be able to figure out relative keys.

Let’s go through the steps to find the relative major of C![]() minor.

minor.

- Count up three diatonic steps (i.e., letter names). Do not worry about accidentals for the first step. Simply count up three letter names.

- C

< D < E

< D < E

- C

- Match the accidentals to figure out the relative major. Is the relative major E major, E

major, or E

major, or E major?

major?

- E major: Yes.

- E

major: Not possible, because E

major: Not possible, because E major is a key with flats, and C

major is a key with flats, and C minor has sharps.

minor has sharps. - E

major: Impossible, because there is no such key as E

major: Impossible, because there is no such key as E major.

major.

- Therefore, the relative major of C

minor is E major. Both keys have four sharps.

minor is E major. Both keys have four sharps.

Now let’s go through the steps to find the relative minor of B major.

- Count down three diatonic steps (i.e., letter names). Do not worry about accidentals for the first step. Simply count down three letter names.

-

- B > A > G

- Match the accidentals to figure out the relative minor. Is the relative major G minor, G

minor, or G

minor, or G minor?

minor?

- G minor: No, because B major has five sharps including G

.

. - G

minor: Impossible, because there is no such key as G

minor: Impossible, because there is no such key as G minor.

minor. - G

minor: Yes.

minor: Yes.

- G minor: No, because B major has five sharps including G

- Therefore, the relative minor of B major is G

minor. Both keys have five sharps.

minor. Both keys have five sharps.

Now we will put together everything we have learned to figure out the key of a musical example in minor (Example 6.5.2).

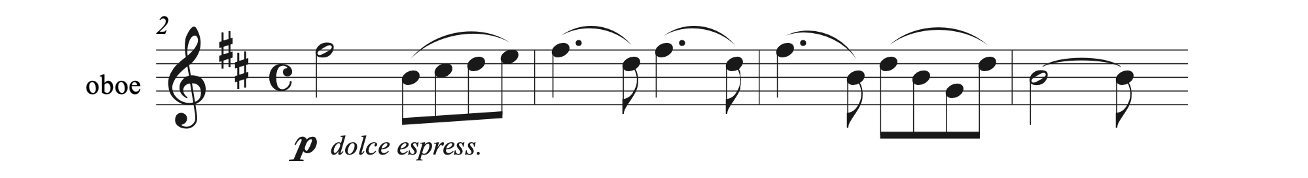

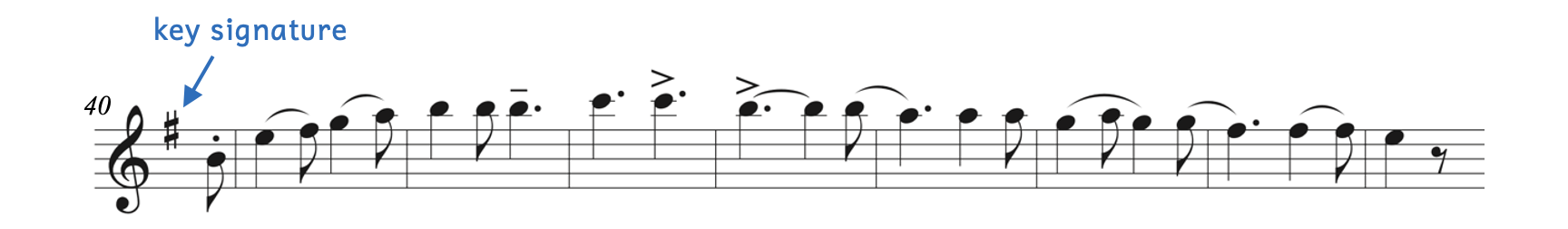

Example 6.5.2. Finding the key: Smetana[5], Má Vlast

When figuring out the key of a single line, the steps are a little different.

- Listen to the example: Does it sound like it’s in major (happy) or minor (sad)?

- Example 6.5.2 sounds like it is in minor.

- Look at the key signature.

- The key signature has one sharp, which is the key of E minor.

Since there is only a single line, we cannot look for the first lowest note and last lowest note. Instead, we must rely on our ears and the key signature.

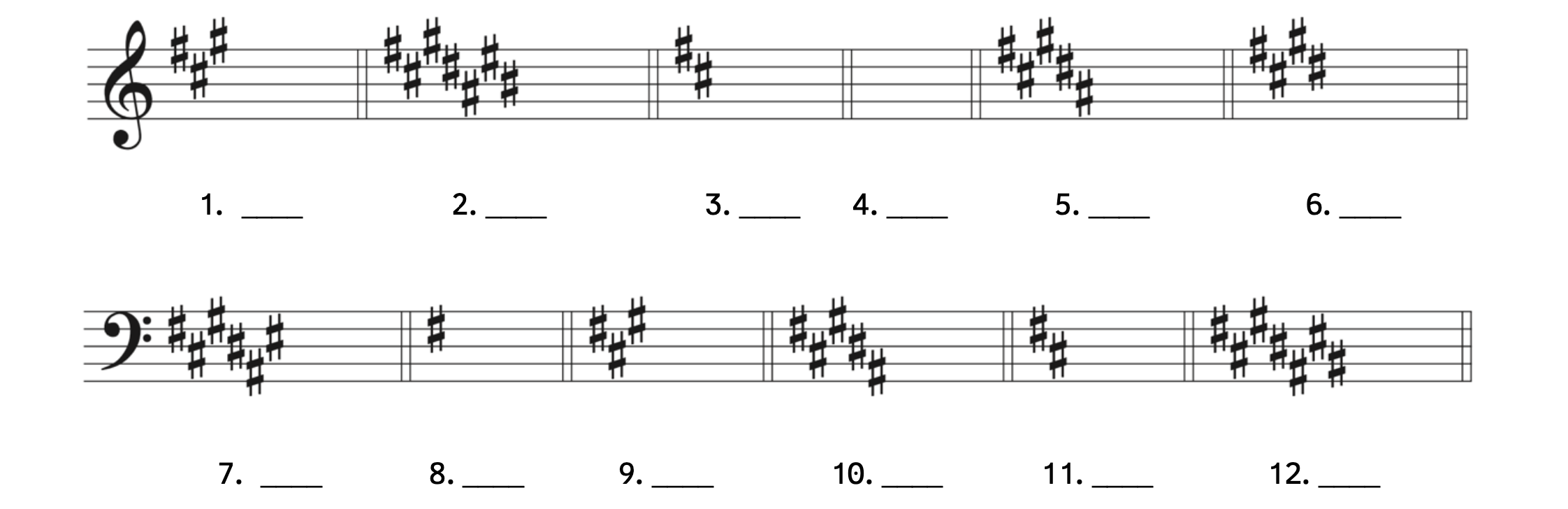

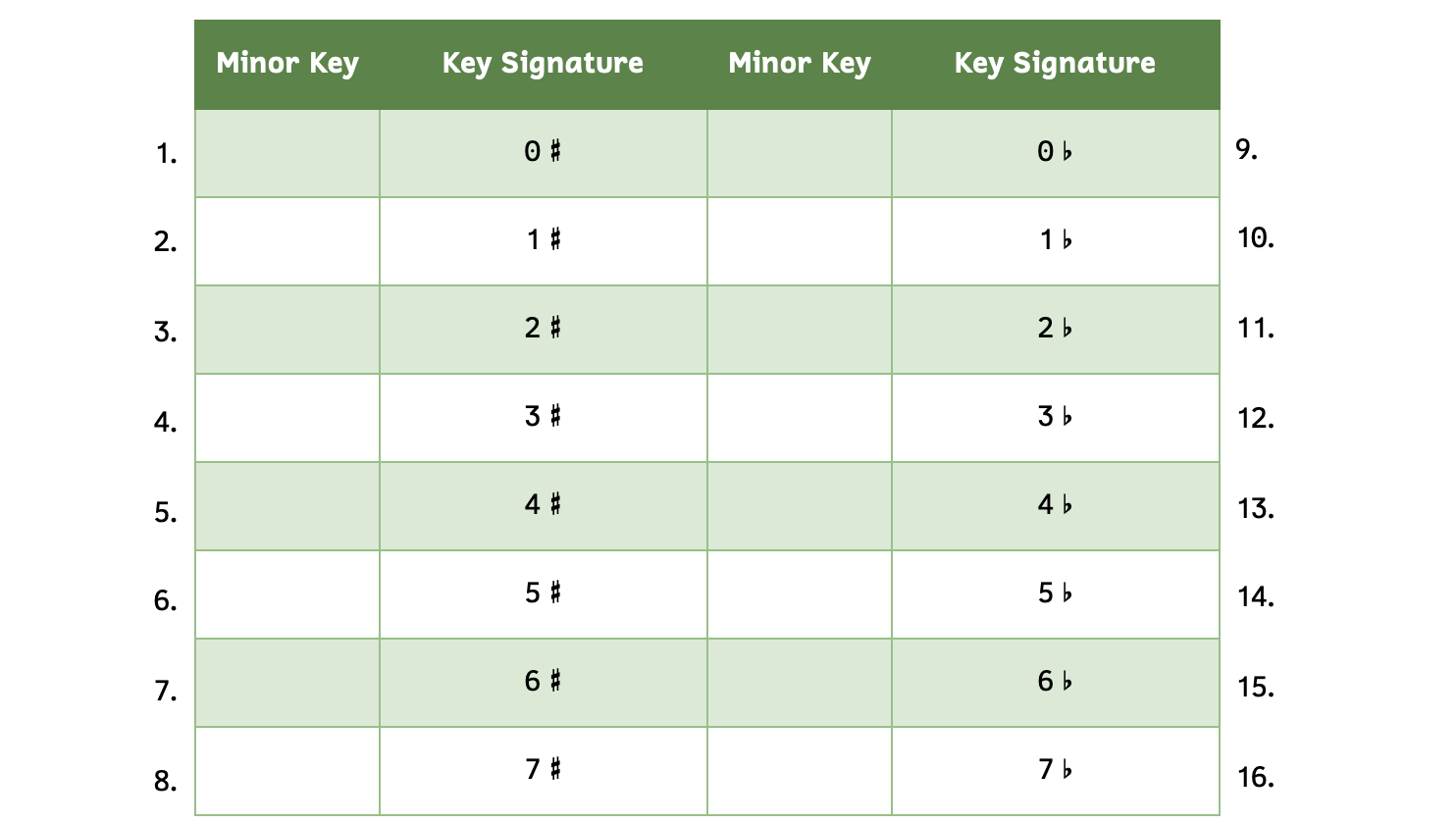

Practice 6.5A. Identifying Minor Key Signatures with Sharps

Directions:

- Identify the minor keys. For minor keys, you only need to write a lowercase letter (e.g., b).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

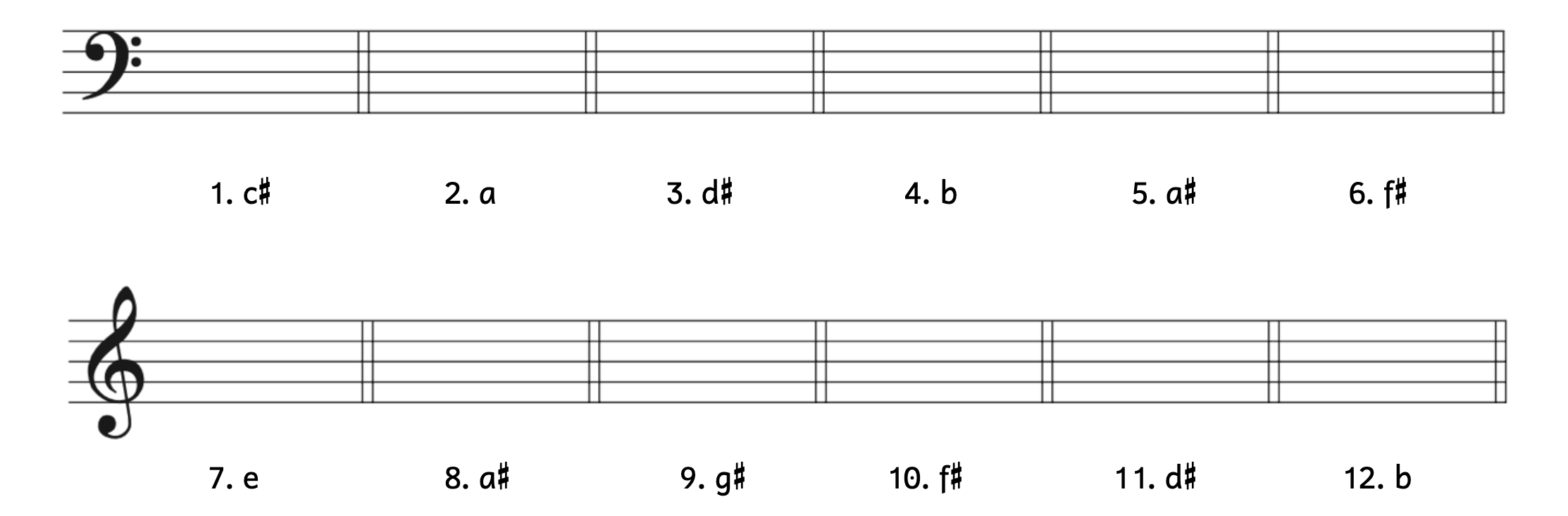

Practice 6.5B. Writing Minor Key Signatures with Sharps

Directions:

- Write the given key signatures on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

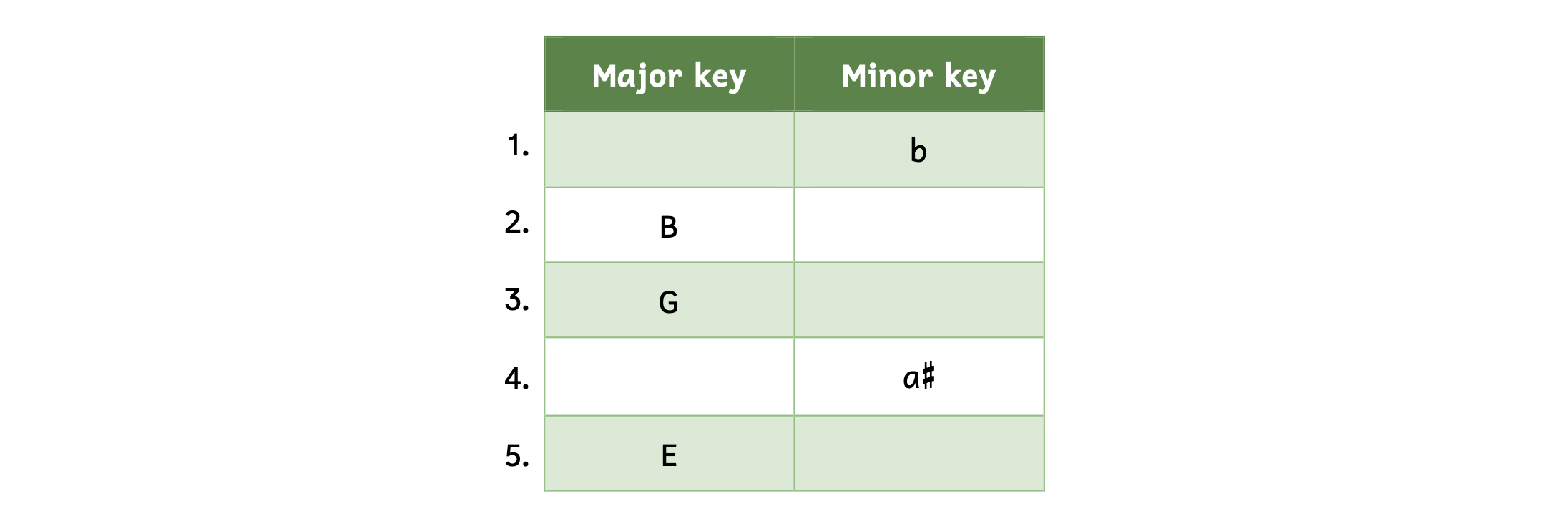

Practice 6.5C. Identifying Relative Keys with Sharps

Directions:

- Write the relative major or minor key in the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Notice the pattern between minor keys with flats and minor keys with sharps.

Example 6.5.3. Minor keys comparison

- Reading across, the note names are the same, but only one has an accidental.

- e.g., D minor and D

minor or E

minor or E minor and E minor

minor and E minor

- e.g., D minor and D

- The number of accidentals equals seven.

- e.g., 1 flat plus 6 sharps or 5 flats plus 2 sharps

- A is the only note name that appears three times.

- A minor has 0 accidentals; A

minor has 7 flats; A

minor has 7 flats; A minor has 7 sharps.

minor has 7 sharps.

- A minor has 0 accidentals; A

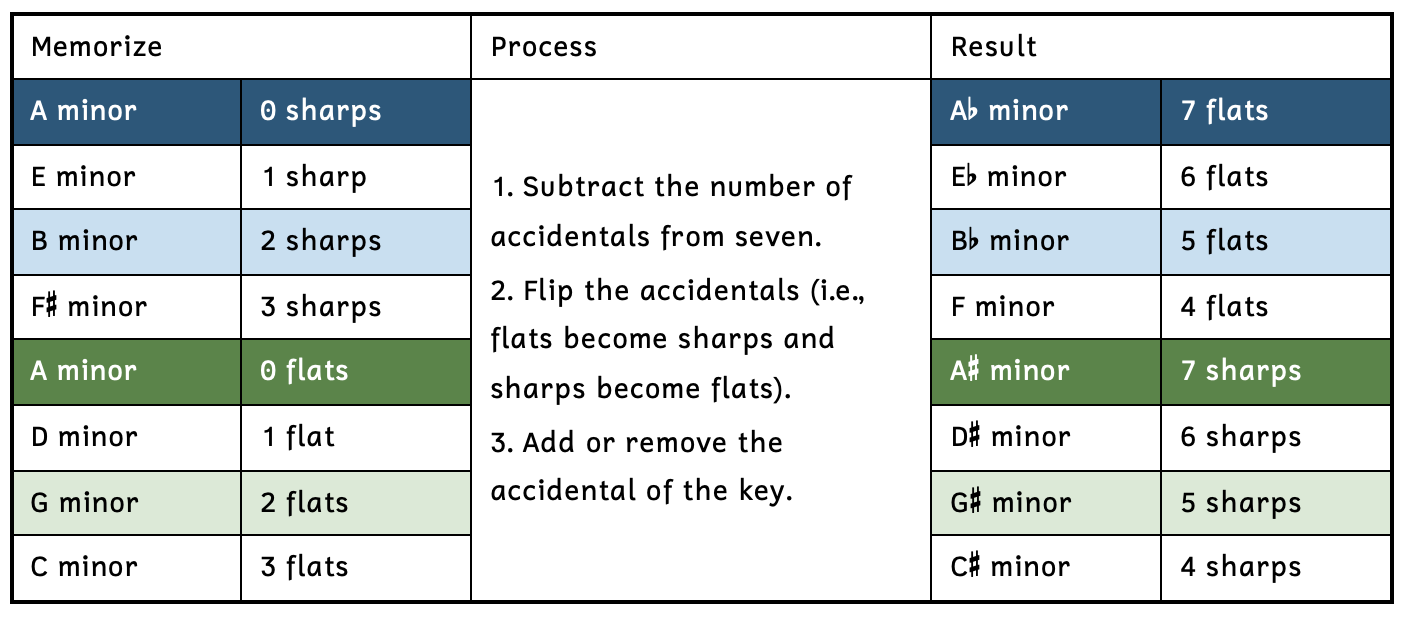

Just as with major keys, if you understand this pattern, you can focus on only memorizing minor keys with three accidentals as a starting point (Example 6.5.4).

Ex. 6.5.4. Memorizing up to three accidentals

In order to use this tip, you must know which keys have sharps and which keys have flats.

- If you memorize that F

minor has three sharps:

minor has three sharps:

- 7 – 3 = 4

- Flip the accidentals: 4 flats

- Add or remove the accidental of the key: F

becomes F

becomes F

- The new key cannot be F

minor because there is no such key as F

minor because there is no such key as F minor.

minor.

- The new key cannot be F

- Therefore, if F

minor has three sharps, F minor has four flats.

minor has three sharps, F minor has four flats.

- If you memorize that D minor has one flat:

- 7 – 1 = 6

- Flip the accidentals: 6 sharps

- Add or remove the accidental of the key: D becomes D

- The new key cannot be D

minor because there is no such key as D

minor because there is no such key as D minor, and the new key signature has sharps.

minor, and the new key signature has sharps.

- The new key cannot be D

- Therefore, if D minor has one flat, D

minor has six sharps.

minor has six sharps.

You can also use this method when identifying key signatures.

- If you are given six flats, but cannot remember the key.

- 7 – 6 = 1

- Flip the accidentals: 1 sharp

- E minor has one sharp. Now add or remove the accidental of the key: E becomes E

.

.

- The key cannot be E

minor because there is no such key as E

minor because there is no such key as E minor, and the given key signature has flats.

minor, and the given key signature has flats.

- The key cannot be E

- Therefore, six flats is the key of E

minor because E minor has one sharp.

minor because E minor has one sharp.

- If you see five sharps, but cannot remember the key.

- 7 – 5 = 2

- Flip the accidentals: 2 flats

- G minor has two flats. Now add or remove the accidental of the key: G becomes G

.

.

- The key cannot be G

minor because there is no such key as G

minor because there is no such key as G minor, and the given key signature has sharps.

minor, and the given key signature has sharps.

- The key cannot be G

- Therefore, five sharps is the key of G

minor because G minor has two flats.

minor because G minor has two flats.

Although you can use this tip when you are starting out, your goal is to confidently know all the major key signatures without any tricks or steps.

Practice 6.5D. Identifying Minor Key Signatures

Directions:

- Identify the minor keys. For minor keys, you only need to write a lowercase letter (e.g., e).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 6.5E. Writing Minor Key Signatures

Directions:

- Write the given key signatures on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 6.5F. Identifying Relative Keys

Directions:

- Write the relative major or minor key in the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

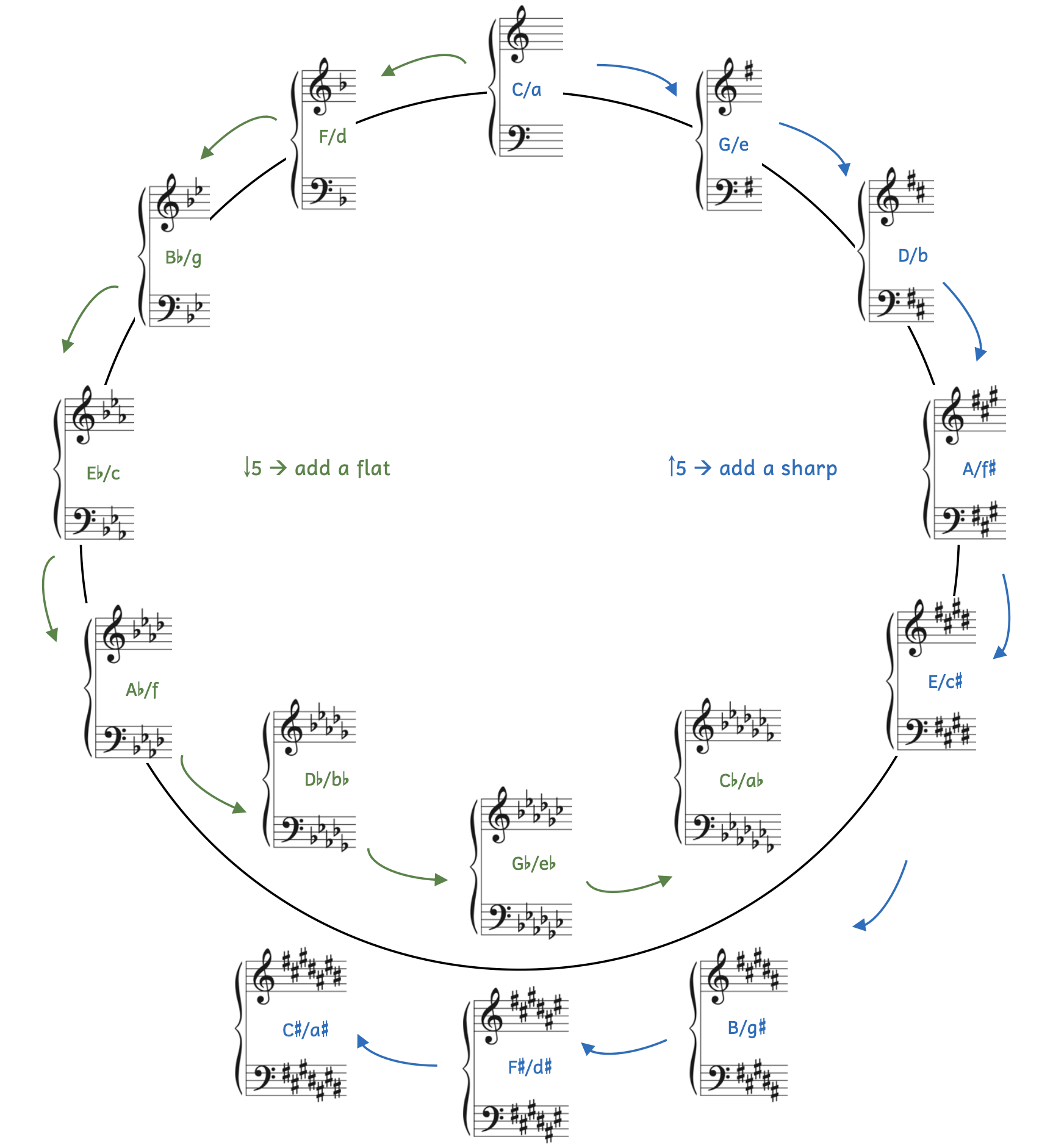

6.6 CIRCLE OF FIFTHS

In Chapter 4, we learned about the circle of fifths: a diagram that showed how all major keys were related by ascending or descending fifths. Now that we know that every major key has a relative minor, we can use the same circle of fifths diagram for minor keys and minor key signatures.

Example 6.6.1 Circle of fifths

Each key in Example 6.6.1 shows the major key and its relative minor. We can find the same information from the circle of fifths for minor keys as we did with major keys.

- Moving clockwise from A minor:

- Each key is a fifth higher.

- A fifth above B minor is F

minor.

minor.

- A fifth above B minor is F

- Each key adds a sharp.

- B minor has 2 sharps and F

minor has 3 sharps.

minor has 3 sharps.

- B minor has 2 sharps and F

- A minor (no sharps, no flats) moves clockwise to A

minor (7 sharps).

minor (7 sharps).

- Each key is a fifth higher.

- Moving counterclockwise from A minor:

- Each key is a fifth lower.

- A fifth below C minor is F minor.

- Each key adds a flat.

- C minor has 3 flats and F minor has 4 flats.

- A minor (no sharps, no flats) moves counterclockwise to A

minor (7 flats).

minor (7 flats).

- Each key is a fifth lower.

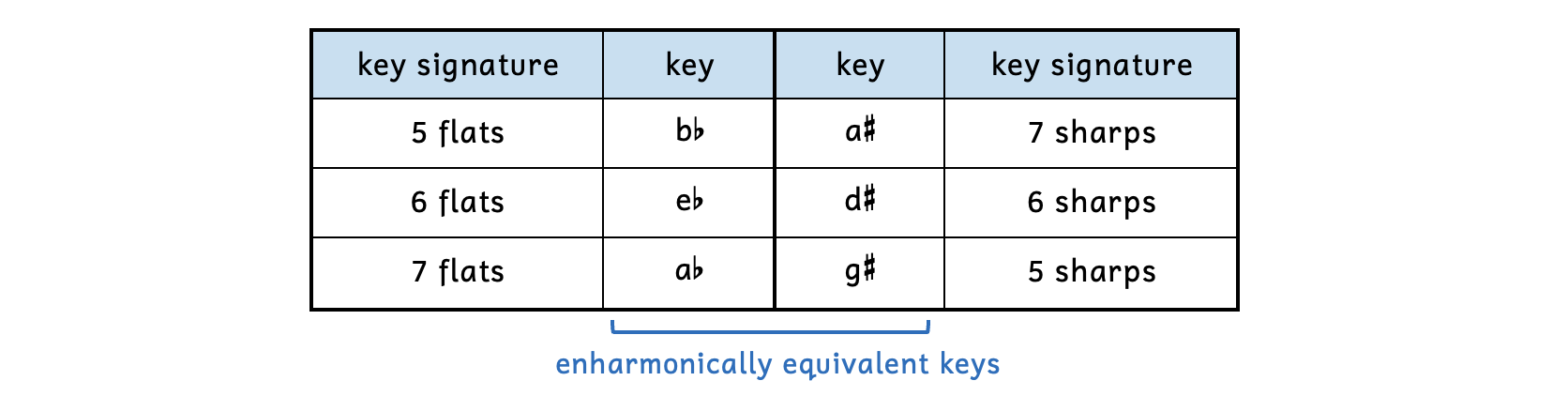

We learned that the three keys on the bottom of the circle of fifths are enharmonically equivalent keys. There are also three minor keys that are enharmonically equivalent.

Example 6.6.2. Enharmonically equivalent keys in minor

E![]() minor is enharmonically equivalent to D

minor is enharmonically equivalent to D![]() minor. Since E

minor. Since E![]() must have flats (since its tonic is E

must have flats (since its tonic is E![]() ) and D

) and D![]() must have sharps (because its tonic is D

must have sharps (because its tonic is D![]() ), E

), E![]() minor has six flats and D

minor has six flats and D![]() minor has six sharps.

minor has six sharps.

Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths is a graphic representation of how all the major and minor keys are built by moving up or down by five. Each key either gains a sharp (clockwise) or gains a flat (counterclockwise).

Practice 6.6. Finding Minor Keys with the Circle of Fifths

Directions:

- Using the circle of fifths, fill in the table. If you do not need the circle of fifths and already have the key signatures memorized, even better.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

6.7 SCALE DEGREES

We learned about scale degrees in Chapter 4. Every note of a major scale has a scale degree number and scale degree name. Similarly, every note of a natural minor scale also has a scale degree number and name.

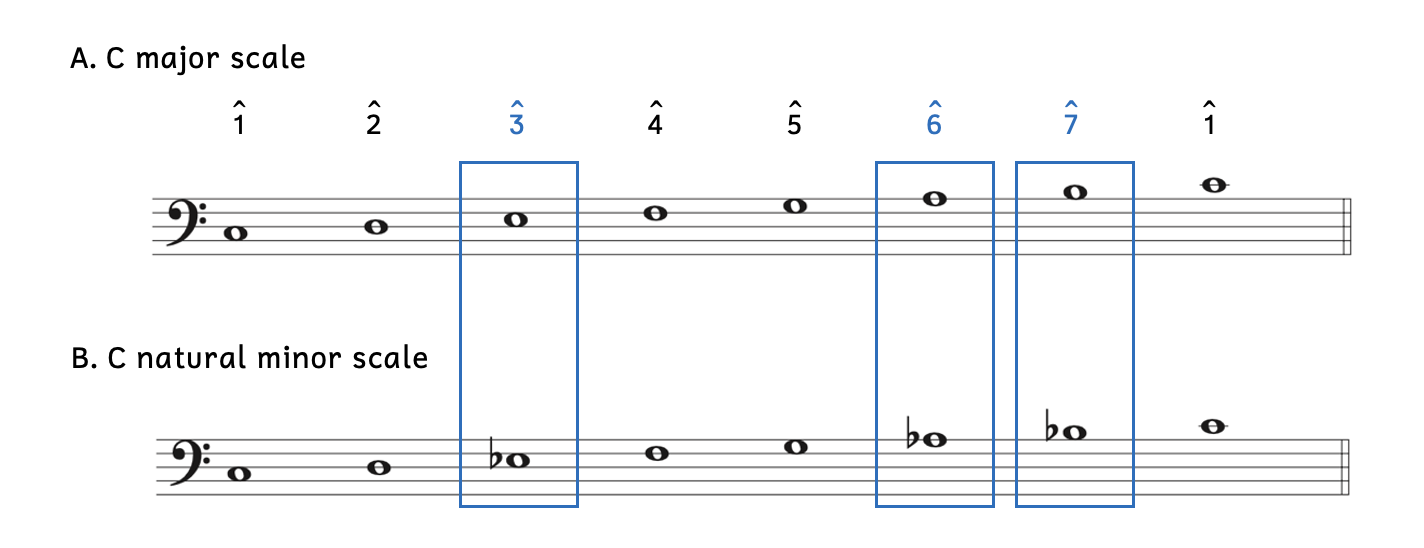

In Example 6.7, differences between the major scale and natural minor scale are boxed and in blue.

Example 6.7. Scale degrees

Although three pitches differ in Examples 6.7A and B, their scale degree numbers do not change. In addition, only one has a different scale degree name.

- The mediant (

) has the same scale degree name and number in major and in minor, although they are different pitches.

) has the same scale degree name and number in major and in minor, although they are different pitches. - The submediant (

) has the same scale degree name and number in major and in minor, although they are different pitches.

) has the same scale degree name and number in major and in minor, although they are different pitches. - Notice that

has the same scale degree number, but different scale degree names and pitches in major and minor.

has the same scale degree number, but different scale degree names and pitches in major and minor.

- In major,

is the leading tone.

is the leading tone. - In minor,

is the subtonic.

is the subtonic.

- In major,

The difference between the leading tone and the subtonic cannot be overstated.

- As we learned, the leading tone leads to tonic: it is only a half step below tonic.

- The subtonic is found only in minor and is a whole step below tonic.

- Recall that the supertonic is a whole step above tonic.

We will later learn that the leading tone can be found in both major and minor. However, the subtonic is unique to minor keys.

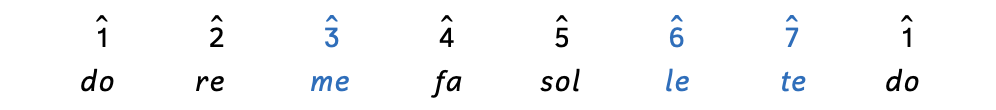

In Chapter 4, we learned that solfège (e.g., do–re–me) is often used in aural training. The three notes that are different in the major scale and natural minor scale use different solfège syllables.

The differences between the major scale and the natural minor scale include the following:

- In major,

is mi; in minor, it is me.

is mi; in minor, it is me. - In major,

is la; in minor, it is le.

is la; in minor, it is le. - In major,

is ti; in the natural minor scale, it is te.

is ti; in the natural minor scale, it is te.

Subtonic Versus Leading Tone

Although ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are different pitches in major and minor, only

are different pitches in major and minor, only ![]() has a different scale degree name.

has a different scale degree name.

- In the natural minor scale,

is a whole step below tonic and is called the subtonic.

is a whole step below tonic and is called the subtonic. - In the major scale,

is a half step below tonic and is called the leading tone.

is a half step below tonic and is called the leading tone.

Practice 6.7. Scale Degrees in the Natural Minor Scale

Directions:

- Answer the following questions based on the given natural minor scale. If it helps, write in the scale degree numbers first.

- Which note is the tonic?

- Which note is the dominant?

- Which note is the subdominant?

- Which note is

?

? - Which note is

?

? - Why is

called the supertonic?

called the supertonic? - Why is

called the subtonic?

called the subtonic? - Which scale degree numbers have different pitches from this scale and the F major scale?

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

6.8 PARALLEL KEYS

We learned that relative keys are major and minor keys that share the same key signature. Parallel keys are major and minor keys that share the same tonic (i.e., note name).

- The parallel minor of C major is C minor.

- The parallel major of F

minor is F

minor is F major.

major. - The parallel major of F

minor is not G

minor is not G major. The tonic (i.e., note name) must be the same, and not enharmonic equivalents.

major. The tonic (i.e., note name) must be the same, and not enharmonic equivalents.

We can discover the relationship between key signatures of parallel keys by comparing their scales.

Example 6.8.1. Scales of parallel keys

All the pitches are the same except for the three pairs of boxed notes, which we learned about in the last section. The relationship between parallel keys is that they differ by three accidentals.

- From a major key, add three flats (or its equivalent) to find the parallel minor.

- From a minor key, add three sharps (or its equivalent) to find the parallel major.

Since most students know major key signatures better, we will find minor key signatures based on the parallel major.

- What is the key signature of F minor?

- The key signature of F major has one flat.

- To find the parallel minor, add three flats (or its equivalent):

- One flat plus three flats equals four flats.

- Therefore, the key signature of F minor has four flats.

- What is the key signature of F

minor?

minor?

- The key signature of F

major has six sharps.

major has six sharps. - To find the parallel minor, add three flats (or its equivalent): Since there are already six sharps, we cannot add three flats. Instead, we remove three sharps:

- Six sharps minus three sharps equals three sharps.

- Therefore, the key signature of F

minor has three sharps.

minor has three sharps.

- The key signature of F

- What is the key signature of G minor?

- The key signature of G major has one sharp.

- To find the parallel minor, add three flats (or its equivalent): Since G major only has one sharp, we cannot simply add three flats. Instead, we remove one sharp and add two flats:

- One sharp minus one sharp plus two flats equals two flats.

- Therefore, the key signature of G minor has two flats.

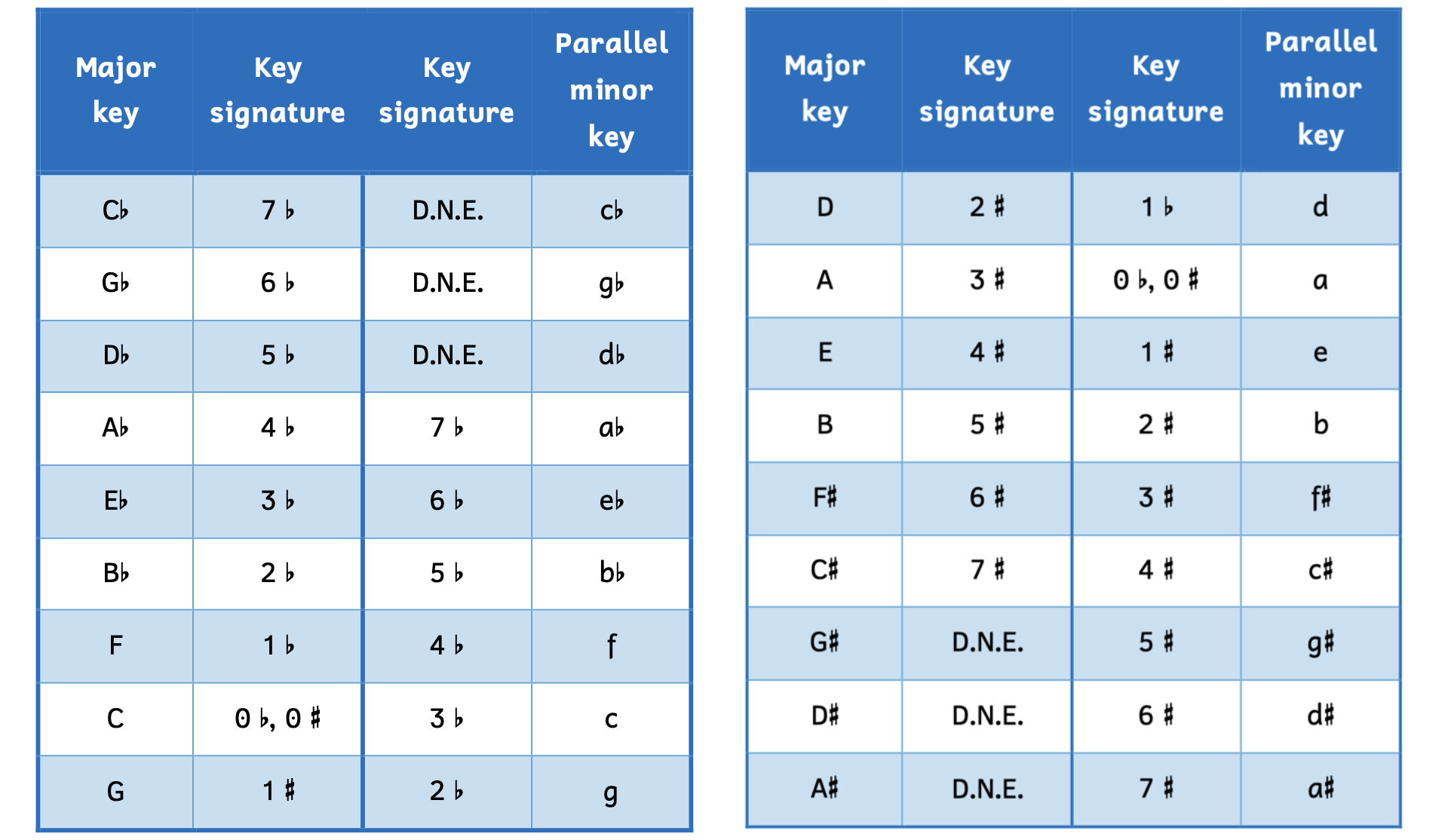

While some students find using parallel keys a great shortcut for figuring out minor keys, the problem is that not all keys exist when using parallel keys (Example 6.8.2). D.N.E. refers to “Does Not Exist.”

Example 6.8.2. Key signatures of parallel keys

Notice that some keys exist in major but not minor (e.g., D![]() major but not D

major but not D![]() minor) and some keys exist in minor but not major (e.g., G

minor) and some keys exist in minor but not major (e.g., G![]() minor but not G

minor but not G![]() major).

major).

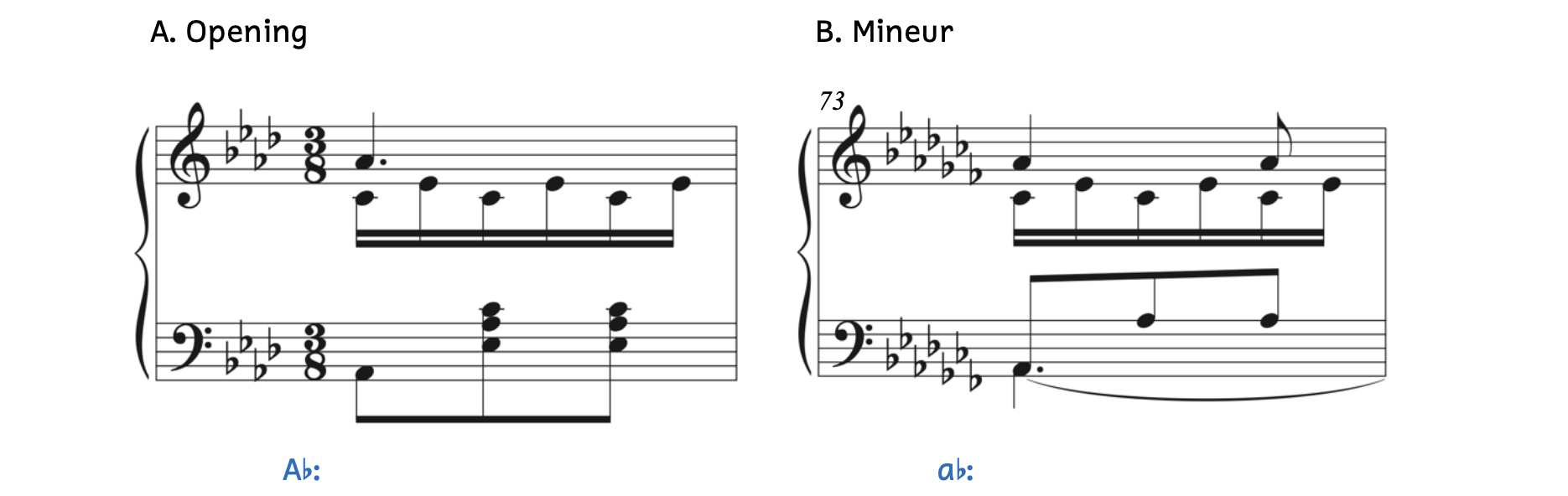

Composers will sometimes take advantage of the parallel relationship between keys as seen in Example 6.8.3.

Example 6.8.3. Parallel keys: Szymanowska[6], Dances for Piano, Cotillon

The cotillion dance in Example 6.8.3A begins in A![]() major. At measure 73 (Example 6.8.3B), Szymanowska changes the key signature to A

major. At measure 73 (Example 6.8.3B), Szymanowska changes the key signature to A![]() minor and writes a variation of the opening melody. She even labels the section “Mineur,” or “Minor” in French. Notice that although the notes appear the same on the page, the music sounds very different because of the key signatures.

minor and writes a variation of the opening melody. She even labels the section “Mineur,” or “Minor” in French. Notice that although the notes appear the same on the page, the music sounds very different because of the key signatures.

In summary, there are four ways to figure out minor key signatures:

- Determine the relative major, which has the same key signature.

- Identify the parallel major and add three flats (or its equivalent).

- Memorize the minor keys up to three accidentals, then use this information to figure out the rest of the keys.

- Simply memorize all 15 minor key signatures. This is ultimately the best option.

Parallel Keys

- Parallel keys share the same tonic.

- To find the key signature of the parallel minor, add three flats (or its equivalent).

Practice 6.8. Identifying Parallel Keys

Directions:

- In the blank, identify the parallel key and in the staff above, write the key signature for both keys.

- For key signatures that do not exist, write DNE.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

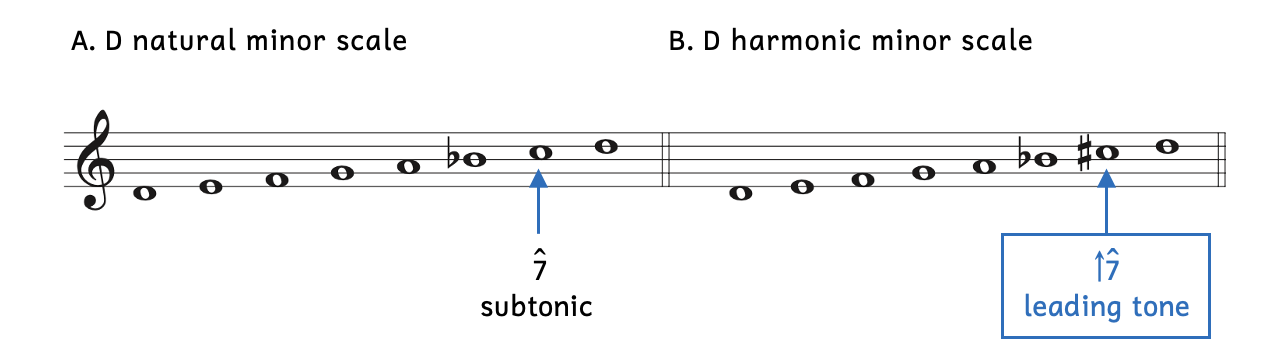

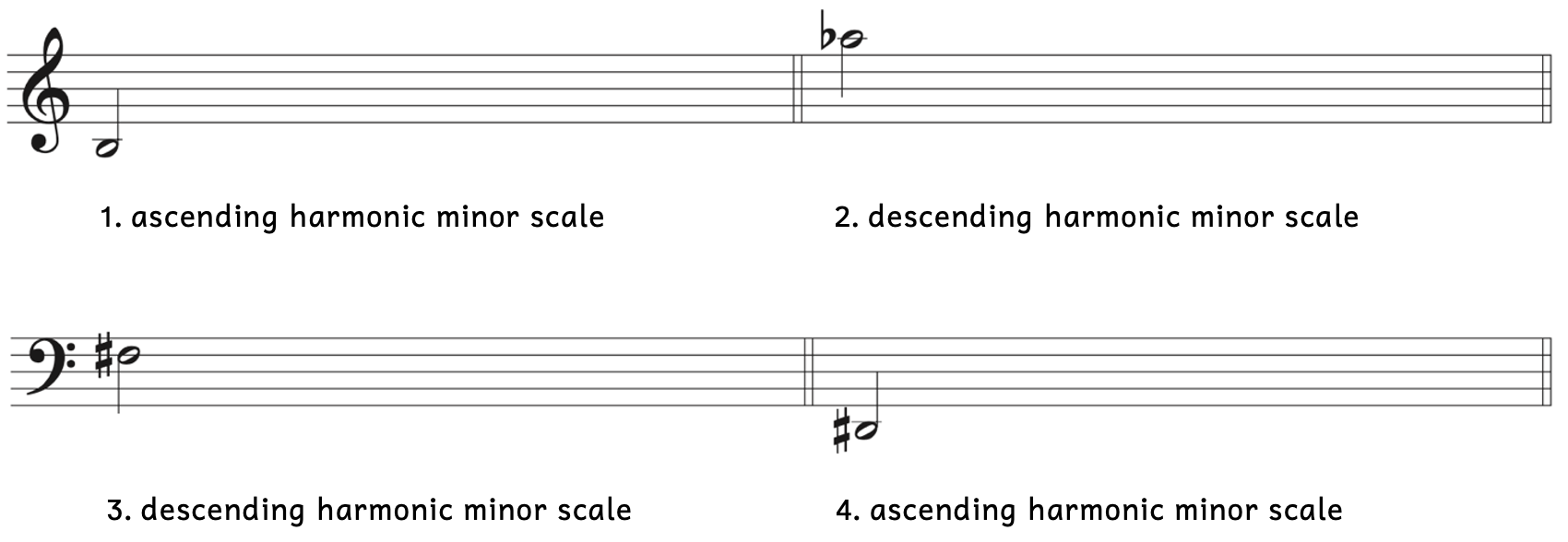

6.9 HARMONIC MINOR SCALE

We learned that in the natural minor scale, ![]() is called the subtonic because it is a whole step below tonic. In major,

is called the subtonic because it is a whole step below tonic. In major, ![]() is only a half step below tonic and is called the leading tone. Being only a half step below tonic gives

is only a half step below tonic and is called the leading tone. Being only a half step below tonic gives ![]() a greater pull to ascend to

a greater pull to ascend to ![]() . Indeed, the majority of steps in the major scale (and the natural minor scale) are whole steps; half steps create a stronger draw.

. Indeed, the majority of steps in the major scale (and the natural minor scale) are whole steps; half steps create a stronger draw.

Because the natural minor scale lacks this strong pull to tonic, we usually change ![]() in minor. Rather than using the subtonic, we raise the subtonic a chromatic half step by using an accidental. By doing so, the subtonic becomes the leading tone and the natural minor scale becomes the harmonic minor scale.

in minor. Rather than using the subtonic, we raise the subtonic a chromatic half step by using an accidental. By doing so, the subtonic becomes the leading tone and the natural minor scale becomes the harmonic minor scale.

Example 6.9.1. Raising the subtonic

- Example 6.9.1A:

- In the D natural minor scale, C belongs to the key signature of D minor and does not have an accidental.

- C is a whole step below tonic and is called the subtonic.

- Example 6.9.1B:

- In the D harmonic minor scale,

(boxed and in blue) is raised so that it is only a half step below tonic.

(boxed and in blue) is raised so that it is only a half step below tonic. - C is raised a half step to C

and is now the leading tone.

and is now the leading tone.

- In the D harmonic minor scale,

Recall that when we learned about the major and natural minor scales, both scales contained only flats or only sharps. With the harmonic minor scale, different accidentals may be used as seen in Example 6.9.1. The D harmonic minor scale has both B![]() and C

and C![]() .

.

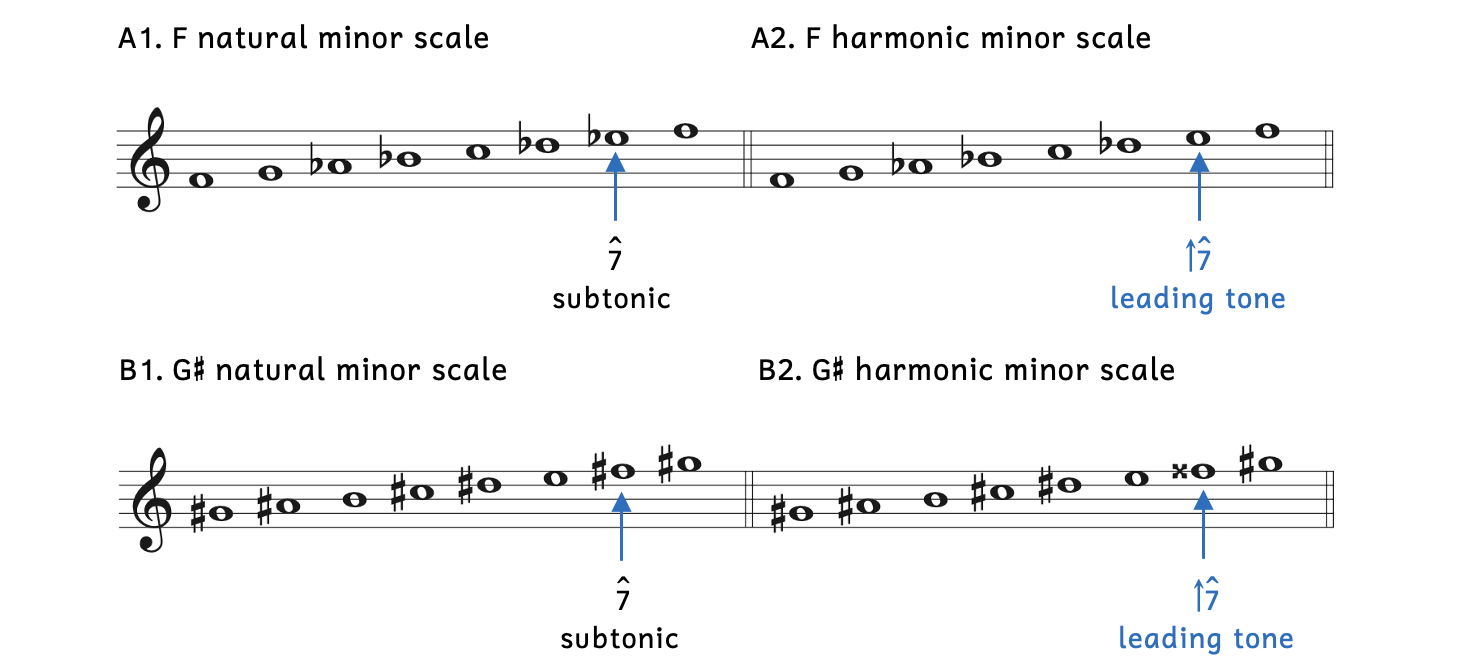

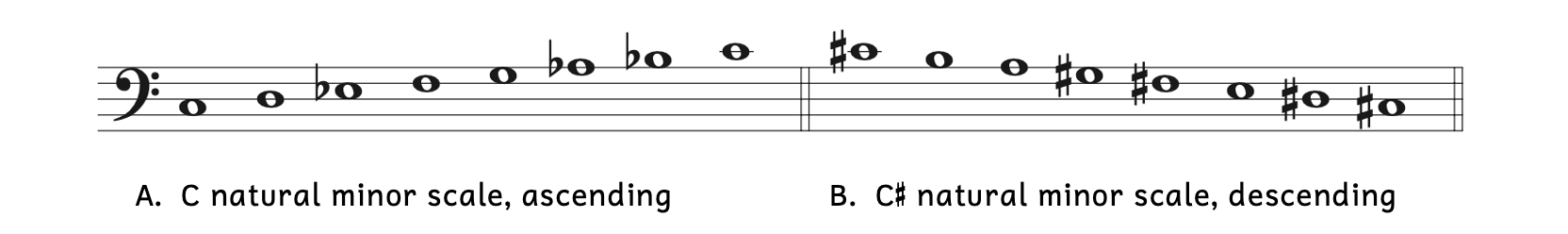

Compare the following natural minor scales with their harmonic minor scales, paying particular attention to the subtonic and leading tone.

Example 6.9.2. Subtonic versus leading tone

- Example 6.9.2A:

- Example 6.9.2A1: In the F natural minor scale, the subtonic is E

.

. - Example 6.9.2A2: In order to raise E

, it becomes E

, it becomes E . Since there is no key signature, the natural sign is not necessary.

. Since there is no key signature, the natural sign is not necessary.

- Example 6.9.2A1: In the F natural minor scale, the subtonic is E

- Example 6.9.2B:

- Example 6.9.2B1: In the G

natural minor scale, the subtonic is F

natural minor scale, the subtonic is F .

. - Example 6.9.2B2: In order to raise F

, it becomes F

, it becomes F .

.

- F

is not the same as G! Remember that major and minor scales are diatonic, meaning they must only use each note name once and only once:

is not the same as G! Remember that major and minor scales are diatonic, meaning they must only use each note name once and only once:  must be F-something.

must be F-something.

- F

- Example 6.9.2B1: In the G

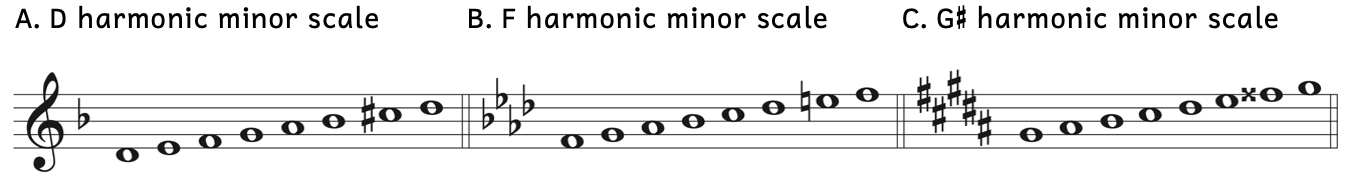

Using the leading tone (instead of the subtonic) in minor keys will always require an accidental. Example 6.9.3 shows the scales from Example 6.9.1 and 6.9.2 with key signatures.

Example 6.9.3. Harmonic minor scales with key signatures

When there is a key signature, raising the subtonic to become the leading tone always requires an accidental on ![]() . The accidental can be a natural (Example 6.9.3B), a sharp (Example 6.9.3A), or a double sharp (Example 6.9.3C).

. The accidental can be a natural (Example 6.9.3B), a sharp (Example 6.9.3A), or a double sharp (Example 6.9.3C).

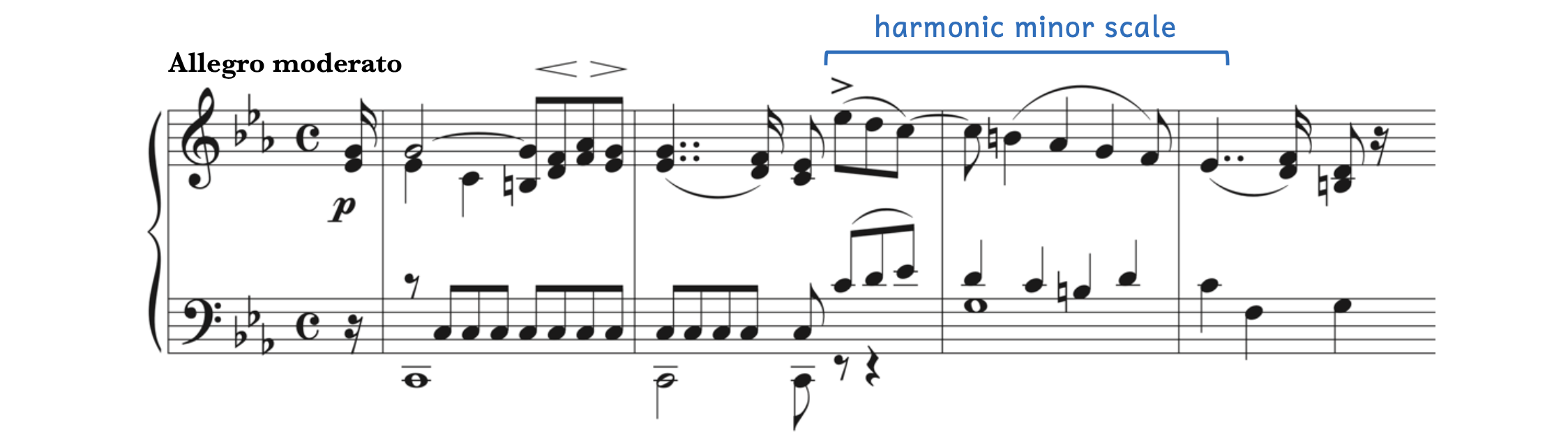

Composers will sometimes use the harmonic minor scale in their music (Example 6.9.4).

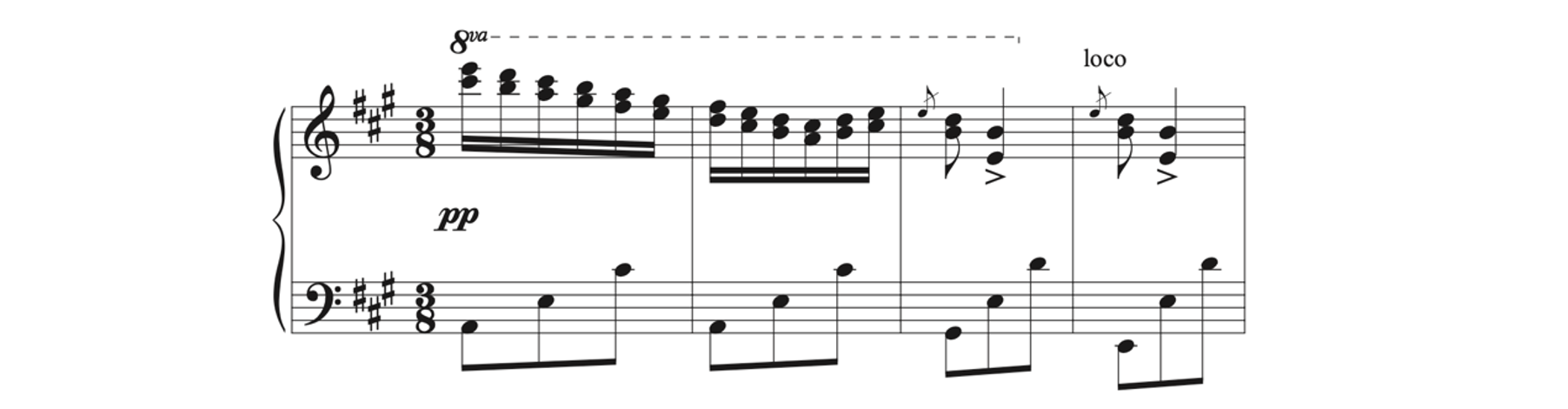

Example 6.9.4. Harmonic minor scale: Liebmann[7], Piano Sonata No. 3, i – Allegro moderato

- The key signature tells us the key is in C minor.

- Liebmann uses a C harmonic minor scale from E

5 to E

5 to E 4 (labeled above).

4 (labeled above).

Sometimes composers will not use the entire harmonic minor scale, but only the portion that makes it different from the natural minor scale (i.e., the submediant and the leading tone, or le and ti) (Example 6.9.5).

Example 6.9.5. Ti and le: Dusikova[8], A Second Set of Airs and a March Arranged as Rondos for Pianoforte, No. 1, Minore

Example 6.9.5 is in D minor. Notice that not only is the C in the treble clef raised with a sharp, but all Cs in the bass clef are also raised. Although every C has a sharp, the key signature does not change: D minor has one flat. In fact, the raised leading tone will never change the key signature. For example, the key signature of F minor has four flats. When we raise the leading tone, E![]() becomes E

becomes E![]() , resulting in three flats. However, the key signature of F minor has four flats and not three flats.

, resulting in three flats. However, the key signature of F minor has four flats and not three flats.

Despite not being in the key signature, the raised leading tone is used in most pieces that are in minor. Again, this is due to the strong pull toward tonic. As a result, we can add another question to our list on how to analyze music (Example 6.9.6).

Example 6.9.6. Analysis: Dussek, Harp Sonata, Op. 3, No. 3, iii – Rondo. Allegro

- Listen to the example: Does it sounds like it’s in major (happy) or minor (sad)?

- Example 6.9.6 sounds like it is in minor.

- Look at the key signature.

- The key signature has three flats, which is the key of C minor.

- Do you see the raised leading tone?

- In C minor, the raised leading tone is B

. Yes, there are two B

. Yes, there are two B s in measure 69.

s in measure 69.

- In C minor, the raised leading tone is B

- Look at the first lowest note.

- The first lowest note is C.

- Look at the last lowest note.

- The last lowest note is C.

The third step is new: Do you see the raised leading tone? Although this step is fairly reliable, the excerpt may include a section that uses only the natural minor scale or does not include ![]() (see Example 6.3.2 and 6.3.3). As usual, it is the combination of the steps on the list that makes for the most convincing analysis.

(see Example 6.3.2 and 6.3.3). As usual, it is the combination of the steps on the list that makes for the most convincing analysis.

Raise the Leading Tone!

Despite the subtonic being found in the natural minor scale and belonging to the minor key signature, the raised leading tone is almost exclusively used in minor. Although we technically raise the subtonic, you will often hear “Raise the leading tone!”

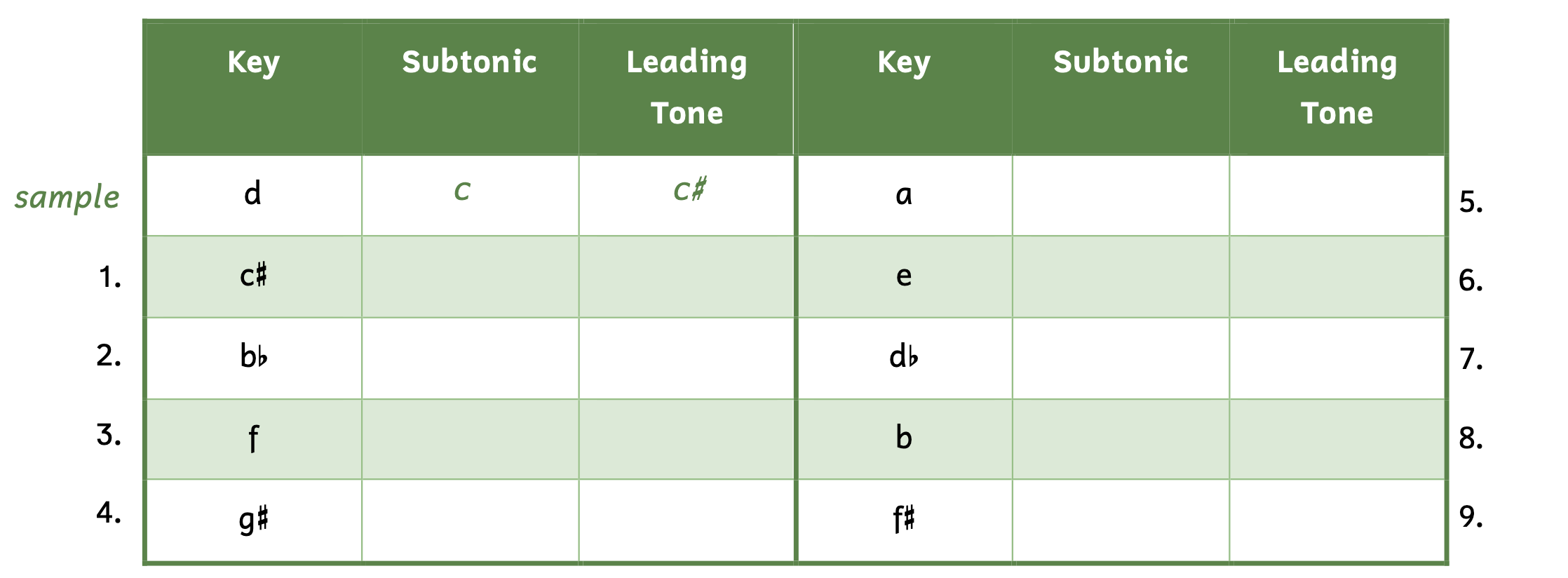

Practice 6.9A. Identifying the Subtonic and Leading Tone

Directions:

- Complete the table.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Practice 6.9B. Identifying Minor Keys for Analysis

Directions:

- What is the key of the given excerpt? Use the steps we learned.

Vespermann[9], Bunte Reihen, op. 6, I. Charakterstück

- Listen to the example: Does it sounds like it’s in major (happy) or minor (sad)?

- Look at the key signature. What is the key signature?

- Do you see the raised leading tone? If so, what is it?

- Look at the first lowest note. What is it?

- Look at the last lowest note. What is it?

- In what key is this excerpt?

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

Practice 6.9C. Labeling Scales in Music

Directions:

- Identify and label the key followed by a colon.

- Label the types of G scales indicated by the brackets.

Mozart[10], Piano Quartet in G Minor, K. 478, i – Allegro

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

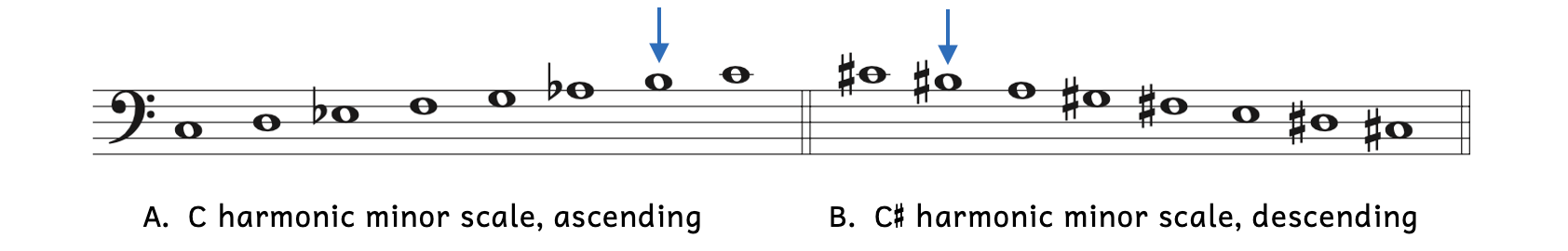

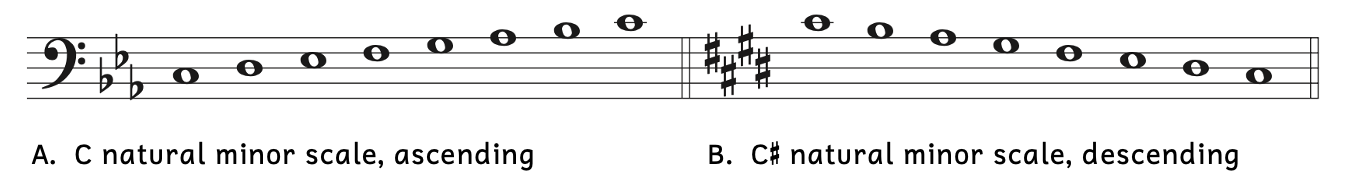

Steps to Writing a Harmonic Minor Scale

When we learned how to write the natural minor scale, we used whole steps and half steps. However, now that we know the minor key signatures (which are based off the natural minor scale), it is much easier to write harmonic minor scales from the minor key signature.

Step one (Example 6.9.7):

Write in all the notes diatonically once and only once in ascending or descending order (alternate line–space or space–line). Do not skip any notes and be sure that the first and last notes are the same notes with the same accidentals.

Example 6.9.7. Step one

Step two (Example 6.9.8):

Write in the accidentals that belong to its minor key. In other words, think of the minor key signature and apply every accidental from that key signature. This creates the natural minor scale. C minor has three flats and C![]() minor has four sharps.

minor has four sharps.

Example 6.9.8. Step two

Step three (Example 6.9.9):

Raise the leading tone: you may need to erase a flat or add a sharp or double sharp. If there is a key signature, you might need to add a natural sign.

Example 6.9.9. Step three

- In Example 6.9.9A,

in the C natural minor scale was B

in the C natural minor scale was B . When raising

. When raising  , B

, B becomes B (Example 6.9.9A). A natural sign is not necessary because there is no key signature.

becomes B (Example 6.9.9A). A natural sign is not necessary because there is no key signature. - In Example 6.9.9B,

in the C

in the C natural minor scale was B. When raising

natural minor scale was B. When raising  , B becomes B

, B becomes B (Example 6.9.9B).

(Example 6.9.9B).

Writing Harmonic Minor Scales Without a Key Signature

- Write in all the note names once and only once in ascending or descending order.

- Write in all the accidentals that belong to the minor key.

- Raise the leading tone.

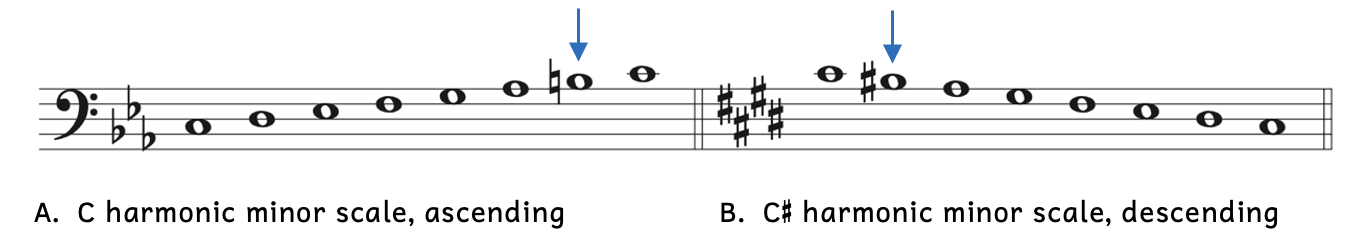

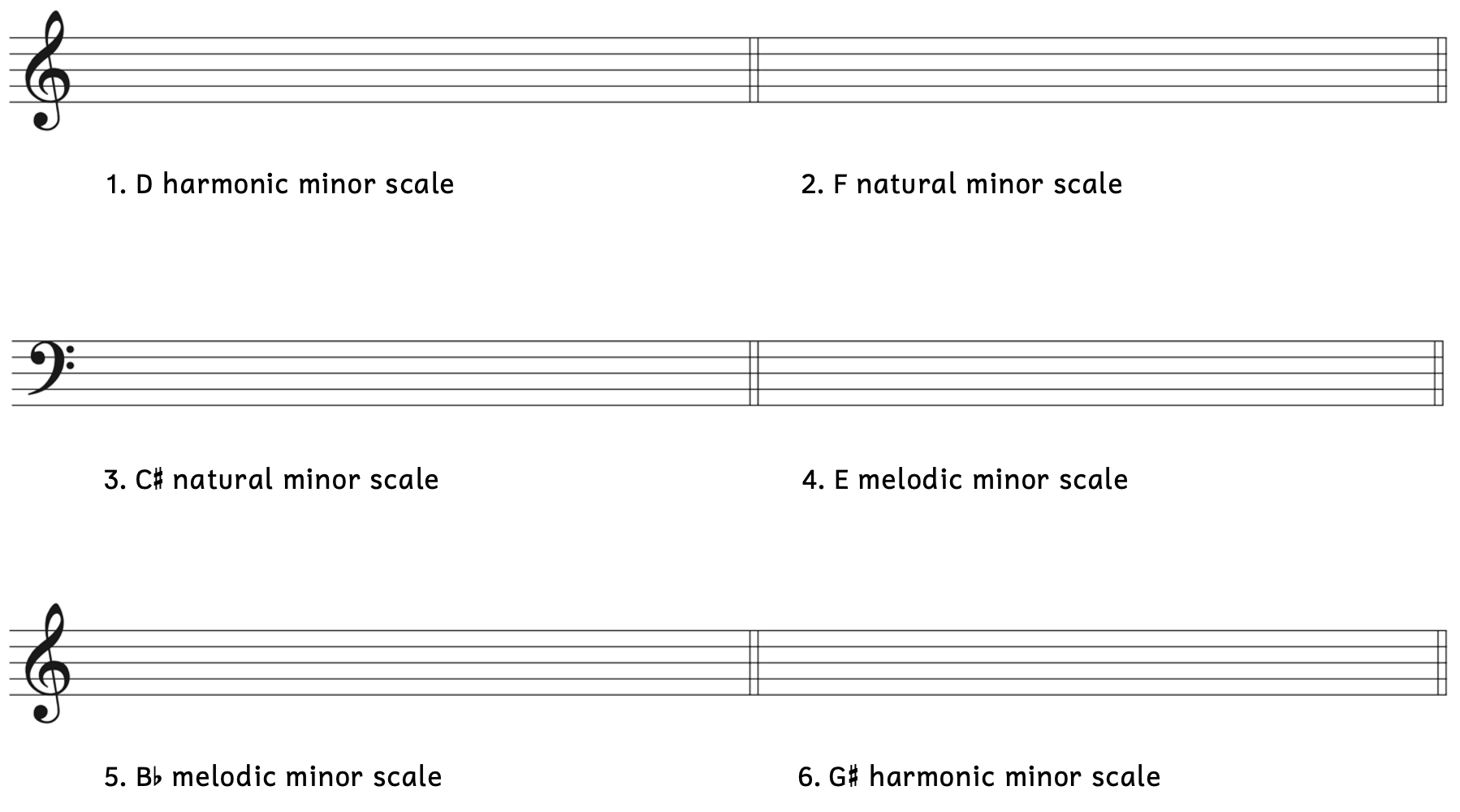

Practice 6.9D. Writing Harmonic Minor Scales Without a Key Signature

Directions:

- Using half notes, construct the following harmonic minor scales on the staff with accidentals. Do not add a key signature. Be aware of stem direction.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

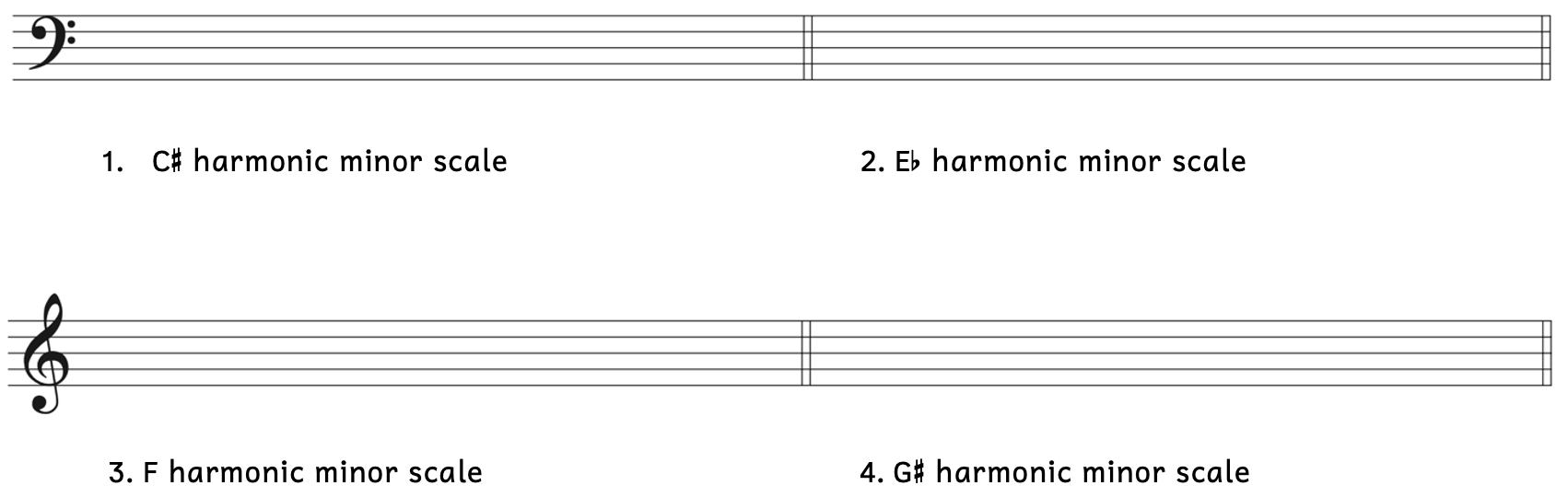

The steps are very similar when writing harmonic minor scales with key signatures.

Step one:

Write in the minor key signature.

Step two (Example 6.9.10):

Write in all the notes diatonically once and only once in ascending or descending order (alternate line–space or space–line). Doing this will create natural minor scales.

Example 6.9.10. Step two

Step three (Example 6.9.11):

Raise the leading tone: With a key signature, you will always add an accidental.

Example 6.9.11. Step three

In Example 6.9.9A, the raised leading tone (B) did not require a natural sign because there was no key signature. However, in Example 6.9.11A, the natural sign is now required.

Writing the harmonic minor scale with or without a key signature always begins from the minor key signature. From there, raise the leading tone.

Writing Harmonic Minor Scales With a Key Signature

- Write the minor key signature.

- Write in all the note names once and only once in ascending or descending order.

- Raise the leading tone.

Practice 6.9E. Writing Harmonic Minor Scales with a Key Signature

Directions:

- Add a key signature but no time signature.

- Using whole notes, write the given harmonic minor scales (ascending only).

Click here to watch the tutorial.

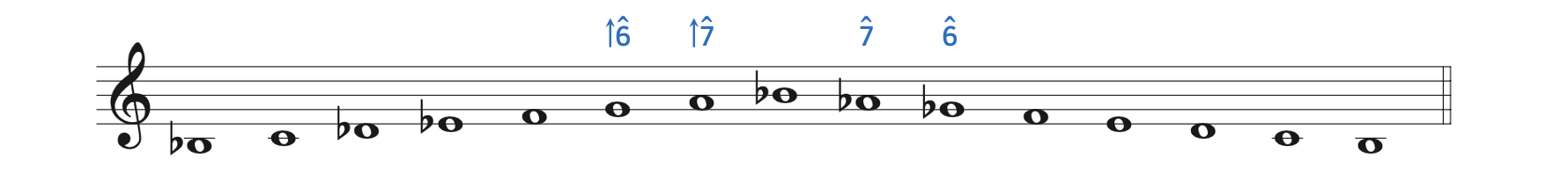

6.10 MELODIC MINOR SCALE

When we first wrote the major scale and the natural minor scale, we used whole steps (w) and half steps (h) (Example 6.10.1).

Example 6.10.1. Whole steps and half steps

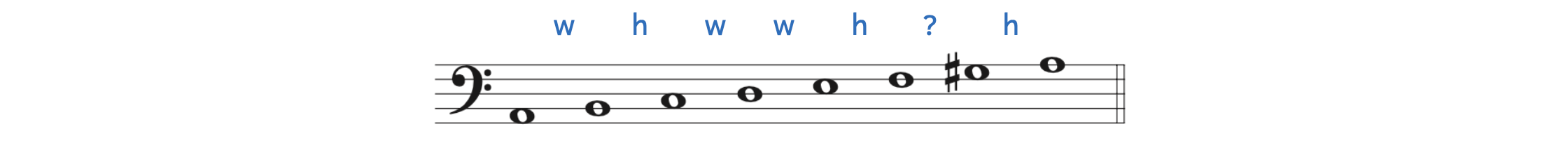

When we wrote the harmonic minor scale, we started with a natural minor scale (based on the minor key signature) and raised the leading tone. However, notice the special distance between the submediant and leading tone that occurs (Example 6.10.2).

Example 6.10.2. Harmonic minor scale

The distance between F and G![]() is more than a whole step. In fact, it is made of three half steps. Listen again to the harmonic minor scale: do you hear the large gap of three half steps?

is more than a whole step. In fact, it is made of three half steps. Listen again to the harmonic minor scale: do you hear the large gap of three half steps?

In order to avoid this large gap, we also raise ![]() , creating the melodic minor scale (Example 6.10.3).

, creating the melodic minor scale (Example 6.10.3).

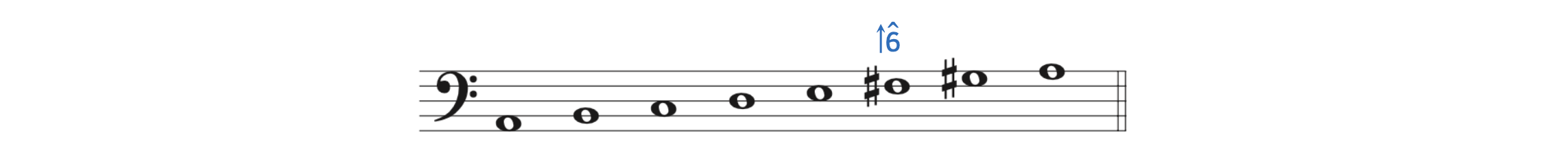

Example 6.10.3. Raising ![]() : The melodic minor scale

: The melodic minor scale

Compare ![]() from Example 6.10.2 to Example 6.10.3. Notice the F has been raised to F

from Example 6.10.2 to Example 6.10.3. Notice the F has been raised to F![]() . Now, the large gap of three half steps disappears and becomes a familiar whole step.

. Now, the large gap of three half steps disappears and becomes a familiar whole step.

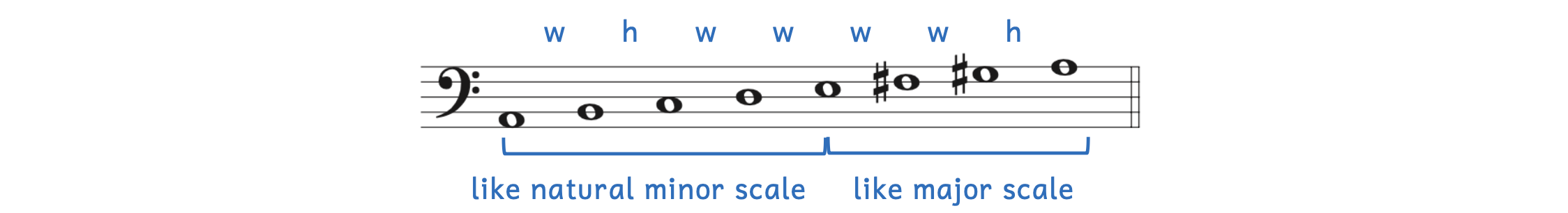

Listen to Example 6.10.4: do you hear that the last half sounds like the major scale? Compare the first half of Example 6.10.4 to the natural minor scale in Example 6.10.1B and the second half of Example 6.10.4 to the major scale in Example 6.10.1A.

Example 6.10.4. Ascending melodic minor scale

Recall that the harmonic minor scale was formed in order to raise the subtonic to become the leading tone so that it led up to tonic by half step. However, when descending from tonic, there is no need to raise the leading tone since ![]() is no longer leading up to tonic. And since

is no longer leading up to tonic. And since ![]() is not raised,

is not raised, ![]() also has no need to be raised. For this reason, the melodic minor scale is different when it ascends and when it descends (Example 6.10.5).

also has no need to be raised. For this reason, the melodic minor scale is different when it ascends and when it descends (Example 6.10.5).

Example 6.10.5. Melodic minor scale

- When ascending,

and

and  are raised so they appear as they do in the major scale.

are raised so they appear as they do in the major scale. - When descending,

and

and  return back to how they appear in the natural minor scale. Notice that the natural sign must be used in Example 6.10.5.

return back to how they appear in the natural minor scale. Notice that the natural sign must be used in Example 6.10.5.

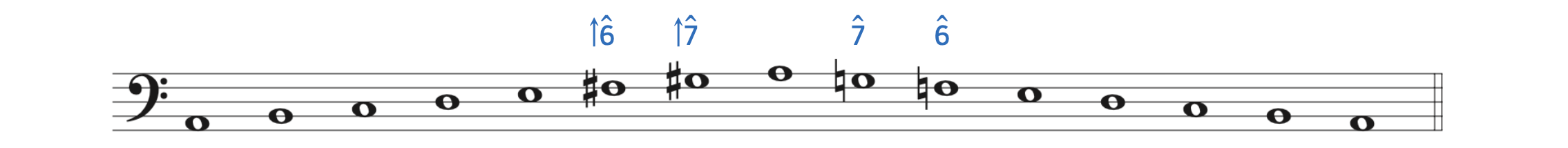

Look at the following melodic minor scales and note which accidentals are used (Example 6.10.6).

Example 6.10.6. Melodic minor scales

- Example 6.10.6A:

- In G minor, the submediant is E

. However, for the ascending melodic minor scale, it is raised to E. We do not need a natural sign since there is no key signature.

. However, for the ascending melodic minor scale, it is raised to E. We do not need a natural sign since there is no key signature. - When descending, a natural sign is required for F since it was previously F

. In addition, E

. In addition, E returns.

returns.

- In G minor, the submediant is E

- Example 6.10.6B:

- In G

minor,

minor,  and

and  are raised to E

are raised to E and F

and F when ascending.

when ascending. - When descending, F

and E

and E (from the melodic minor scale) return.

(from the melodic minor scale) return.

- In G

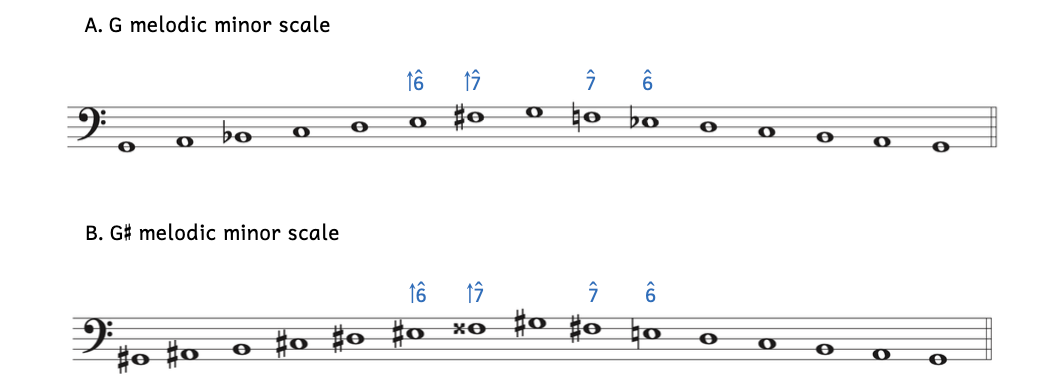

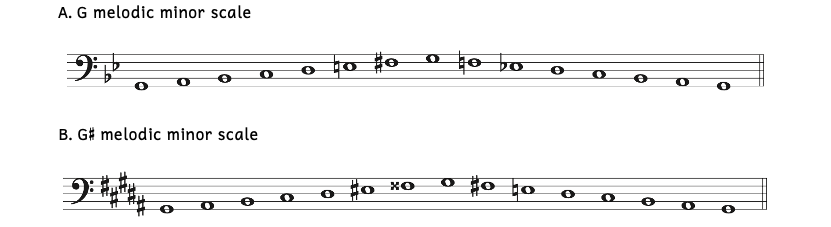

Example 6.10.7 shows the scales from Example 6.10.6 with key signatures.

Example 6.10.7. Melodic minor scales with key signatures

When there is a key signature, the altered notes become obvious. Only ![]() and

and ![]() have accidentals. The raised accidental can be a natural, a sharp, or a double sharp. The lowered accidental can be a sharp, a natural, or a flat.

have accidentals. The raised accidental can be a natural, a sharp, or a double sharp. The lowered accidental can be a sharp, a natural, or a flat.

Some students find it helpful to think of the melodic minor scale in terms of solfège for ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() .

.

- While ascending, the four syllables would be sol-la-ti-do. In minor, this means le must be raised to la and te must be raised to ti.

- While descending, the four syllables would be do-te-le-sol, which means they must return to the natural minor.

Many melodies in minor will use the ![]() –raised

–raised ![]() –raised

–raised ![]() –

–![]() (sol-la-ti-do) of the ascending melodic minor scale, as in Dukas’s famous The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

(sol-la-ti-do) of the ascending melodic minor scale, as in Dukas’s famous The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

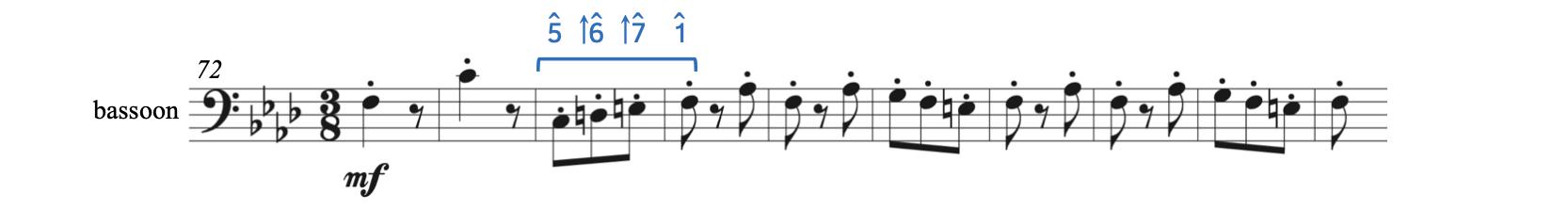

Example 6.10.8. Ascending melodic minor scale: Dukas[11], The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Example 6.10.8 is in F minor. As the melody ascends from ![]() (C) to

(C) to ![]() (F) in measures 74-75,

(F) in measures 74-75, ![]() (D) and

(D) and ![]() (E) are raised, utilizing the melodic minor scale (sol-la-ti-do).

(E) are raised, utilizing the melodic minor scale (sol-la-ti-do).

Composers can make use of both the ascending and descending melodic minor scale, as in Example 6.10.9.

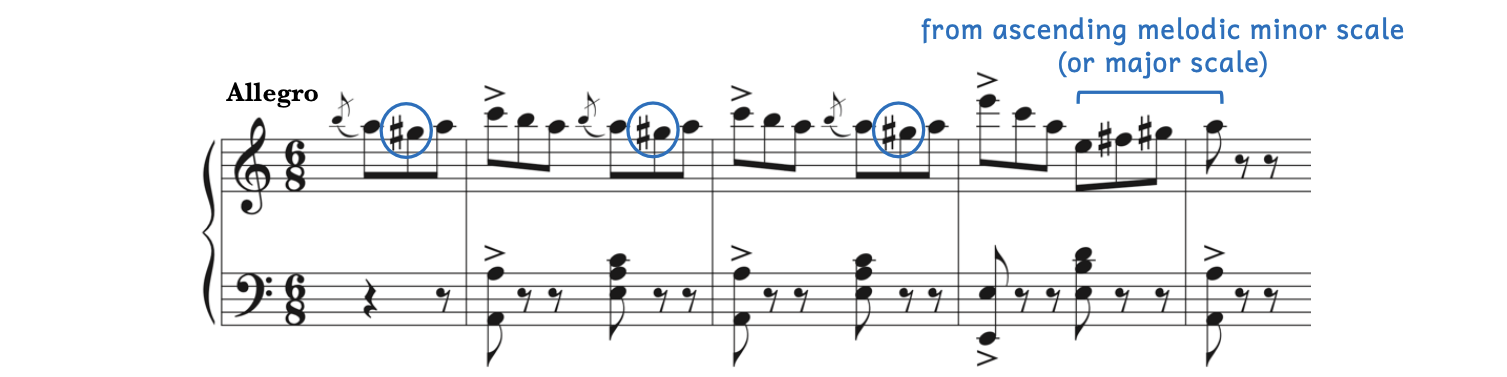

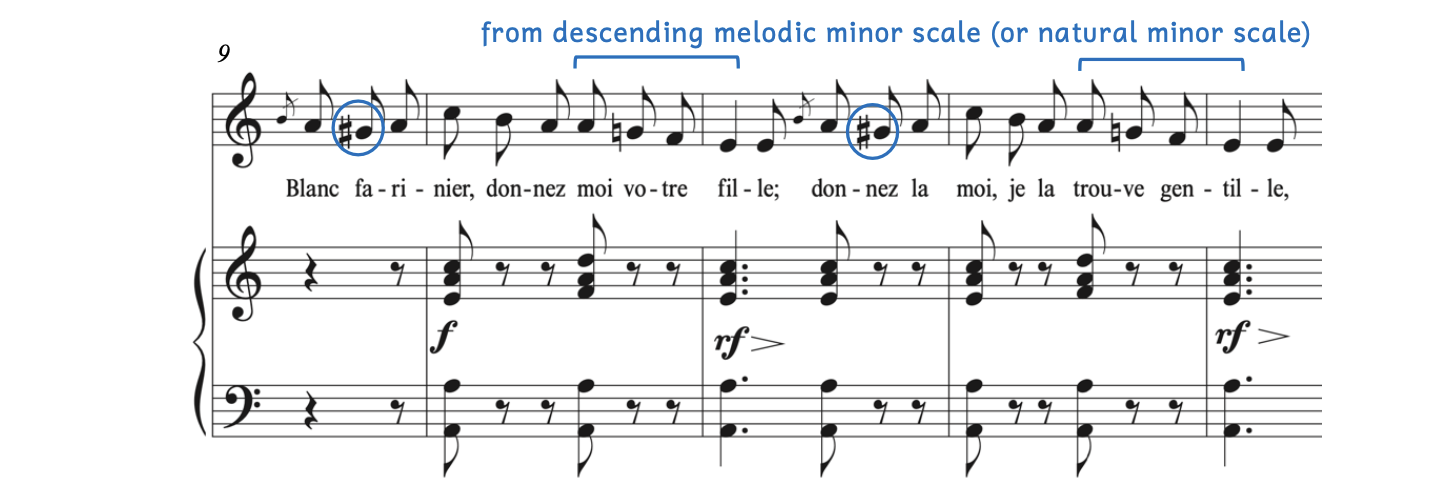

Example. 6.10.9. Melodic minor scale: Puget[12], La Chanson du Charbonnier

A. Opening

B. Vocalist’s opening

Puget’s song is in A minor and as usual, we see a number of raised leading tones (circled G![]() s).

s).

- Example 6.10.9A: In the piano introduction, Puget raises

and

and  in measure 3 as

in measure 3 as  ascends to

ascends to  (sol-la-ti-do). These four notes belong to the ascending melodic minor scale (as well as the major scale).

(sol-la-ti-do). These four notes belong to the ascending melodic minor scale (as well as the major scale). - Example 6.10.9B: The vocalist begins in measure 9 and utilizes the descending melodic minor scale as

and

and  are no longer raised. These four notes—

are no longer raised. These four notes— descending to

descending to  (do-te-le-sol)—also belong to the natural minor scale.

(do-te-le-sol)—also belong to the natural minor scale.

Like the harmonic minor scale, the accidentals used to raise ![]() and

and ![]() do not change the key signature. In Example 6.10.9A, every F and G that appear are F

do not change the key signature. In Example 6.10.9A, every F and G that appear are F![]() and G

and G![]() . However, the key signature for A minor does not have any sharps; A minor has zero sharps.

. However, the key signature for A minor does not have any sharps; A minor has zero sharps.

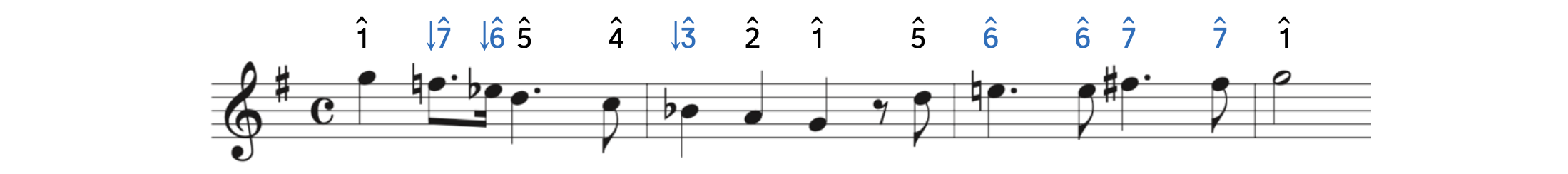

Practice 6.10A. Identifying the Melodic Minor Scale in Music

Directions:

- Identify and label the key followed by a colon.

- Identify and label parts of the ascending or descending melodic minor scale.

Wieck Schumann[13], Piano Sonata in G Minor, i – Allegro

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Steps to Writing a Melodic Minor Scale

As we did with harmonic minor scales, we will write melodic minor scales based on the minor key signature.

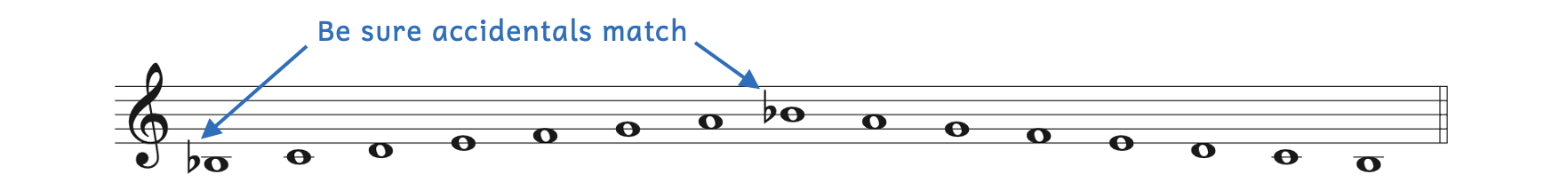

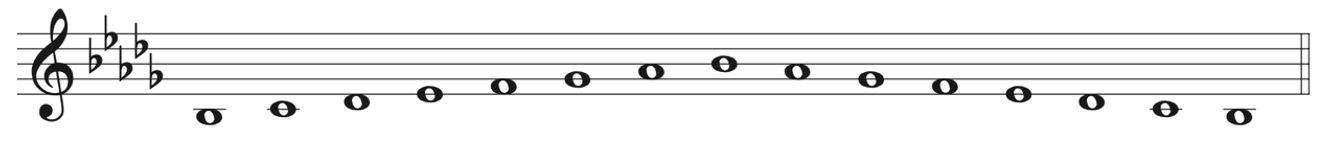

Step one (Example 6.10.10):

Write in all the notes once and only once in ascending and descending order (alternate line–space or space–line). Do not skip any notes and be sure that the first and last notes are the same notes with the same accidentals.

Example 6.10.10. Step one

Step two (Example 6.10.11):

Write in the accidentals that belong to its minor key. In other words, think of the minor key signature and apply every accidental from that key signature. This creates the natural minor scale. B![]() minor has five flats.

minor has five flats.

Example 6.10.11. Step two

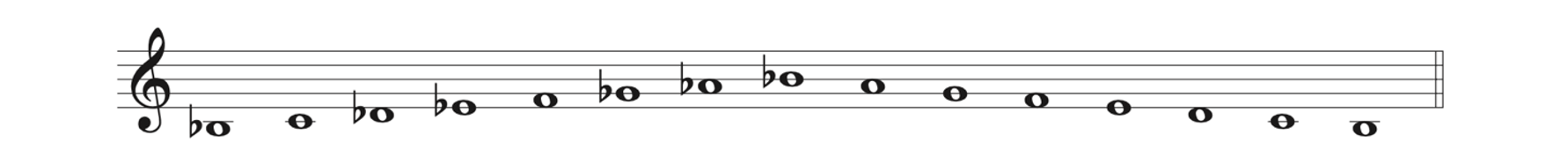

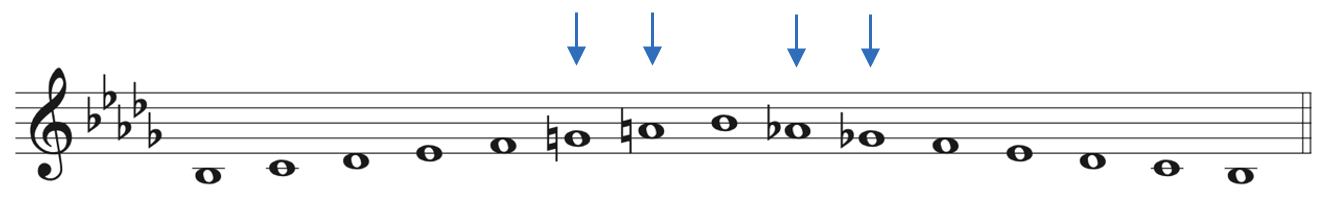

Step three (Example 6.10.12):

Raise ![]() and

and ![]() on the way up, and return

on the way up, and return ![]() and

and ![]() back to the natural minor on the way down (Example 6.10.12).

back to the natural minor on the way down (Example 6.10.12).

Example 6.10.12. Step three

- When ascending,

(G-flat) and

(G-flat) and  (A-flat) are raised to G

(A-flat) are raised to G and A

and A . The natural signs are not necessary, since there is no key signature. In this case, you would simply erase the flats.

. The natural signs are not necessary, since there is no key signature. In this case, you would simply erase the flats. - When descending, return to the natural minor scale, restoring the flats back to

(A

(A ) and

) and  (G

(G ).

).

Writing Melodic Minor Scales Without a Key Signature

- Write in all the note names once and only once in ascending or descending order.

- Write in all the accidentals that belong to the minor key.

- Raise

and

and  during the ascent, and return

during the ascent, and return  and

and  back to the natural minor during the descent.

back to the natural minor during the descent.

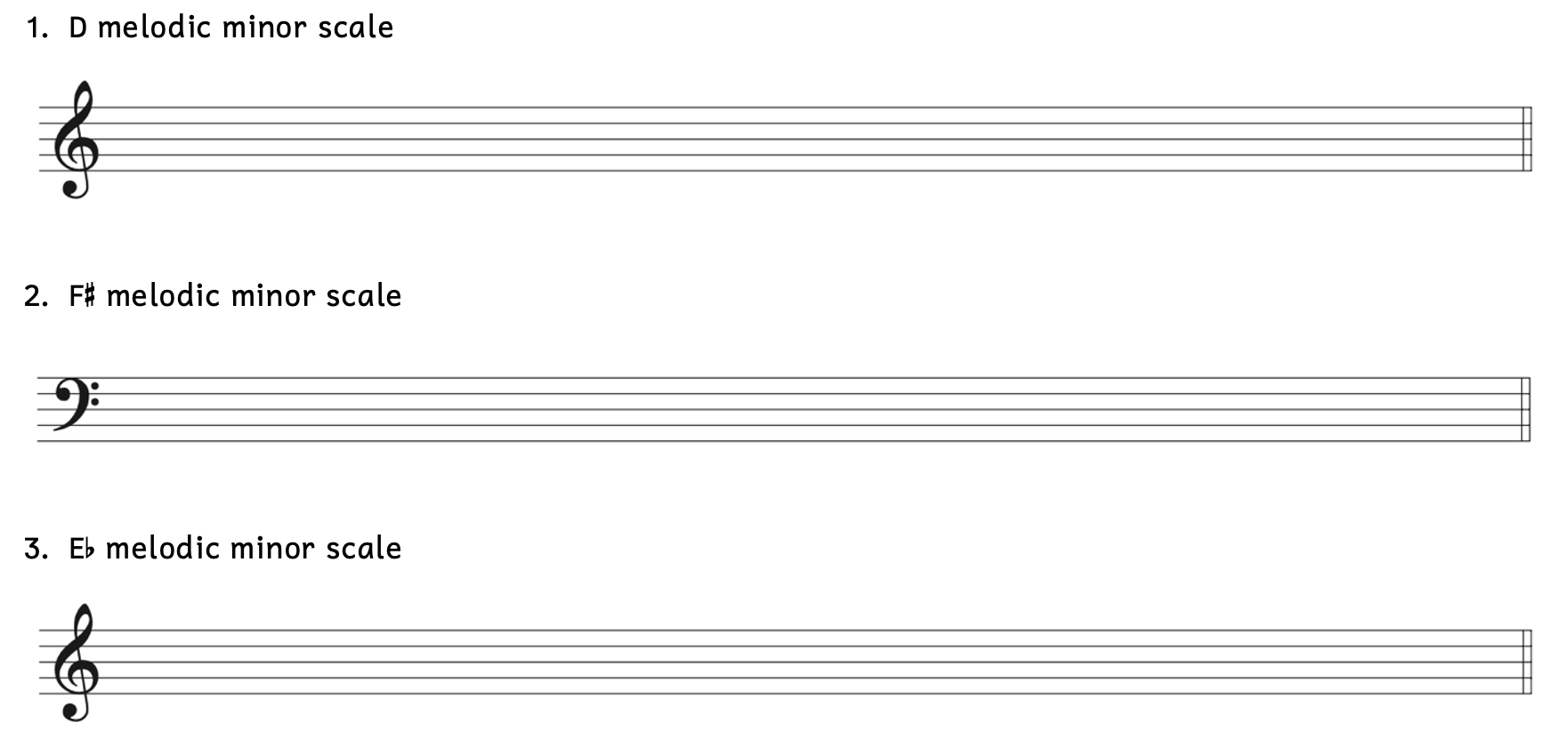

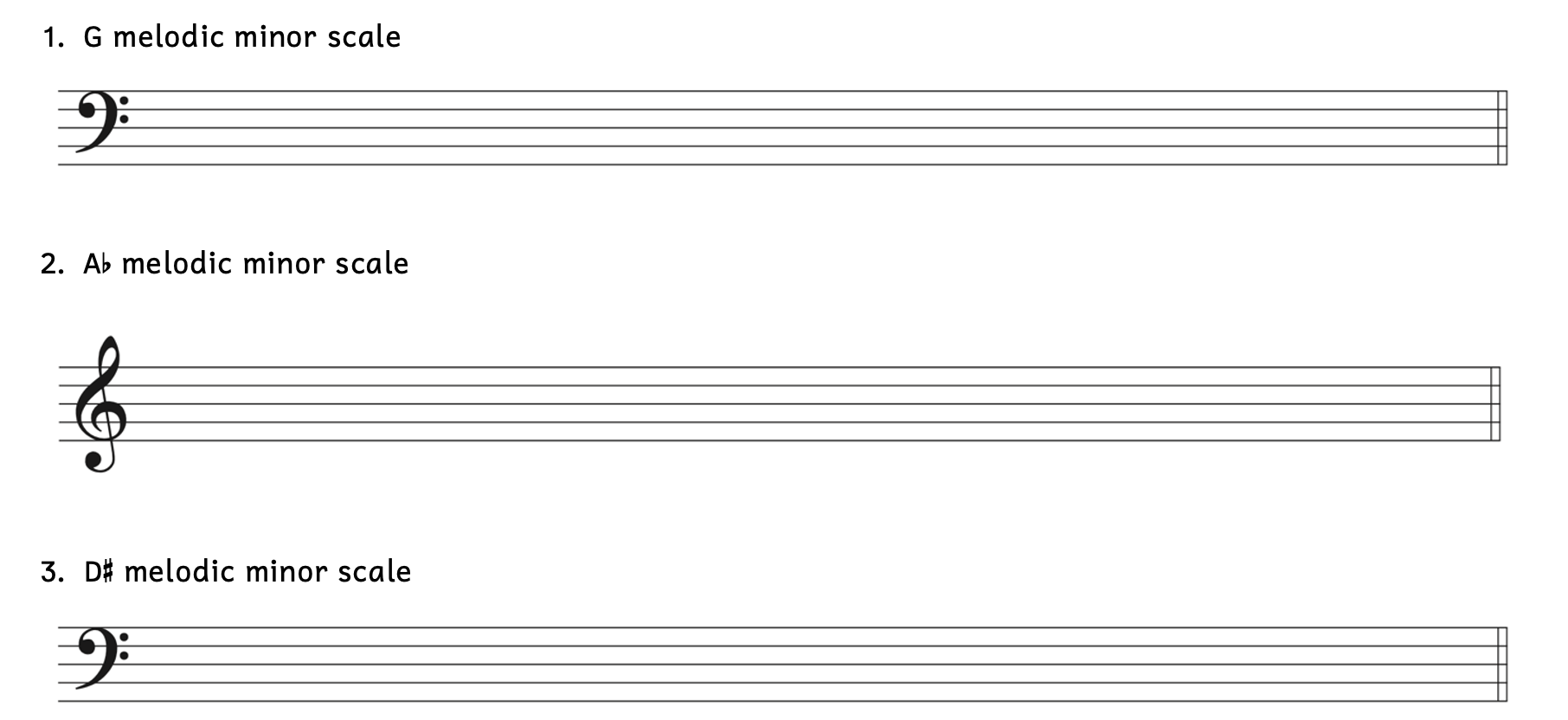

Practice 6.10B. Writing Melodic Minor Scales Without a Key Signature

Directions:

- Construct the following melodic minor scales on the staff using whole notes.

- For all melodic minor scales, always write the scale both ascending and descending.

- Use accidentals; do not use a key signature.

- Do not add a time signature.

- Do not add bar lines.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

The steps are very similar when writing melodic minor scales with key signatures.

Step one: Write in the minor key signature.

Step two (Example 6.10.13):

Write in all the notes diatonically once and only once in ascending and descending order (alternate line–space or space–line). Doing this will create natural minor scales.

Example 6.10.13. Step two

Step three (Example 6.10.14):

Raise ![]() and

and ![]() on the way up, and lower

on the way up, and lower ![]() and

and ![]() back to the natural minor scale on the way down. There should always be four accidentals if there are no bar lines.

back to the natural minor scale on the way down. There should always be four accidentals if there are no bar lines.

Example 6.10.14. Step three

The trickiest thing to remember when writing the melodic minor scale is remembering which accidentals to use on the way down. Always refer back to the key signature.

Writing the melodic minor scale with or without a key signature always begins from the minor key signature. From there, raise ![]() and

and ![]() on the way up, and lower

on the way up, and lower ![]() and

and ![]() back to the natural minor scale on the way down.

back to the natural minor scale on the way down.

Writing Melodic Minor Scales with a Key Signature

- Write in the key signature.

- Write in all the note names once and only once in ascending or descending order.

- Raise

and

and  during the ascent, and return

during the ascent, and return  and

and  back to the natural minor during the descent.

back to the natural minor during the descent.

Practice 6.10C. Writing Melodic Minor Scales with a Key Signature

Directions:

- Write the key signature for the given keys.

- Construct the following melodic minor scales on the staff using whole notes.

- For all melodic minor scales, always write the scale both ascending and descending.

- Do not add a time signature.

- Do not add bar lines.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

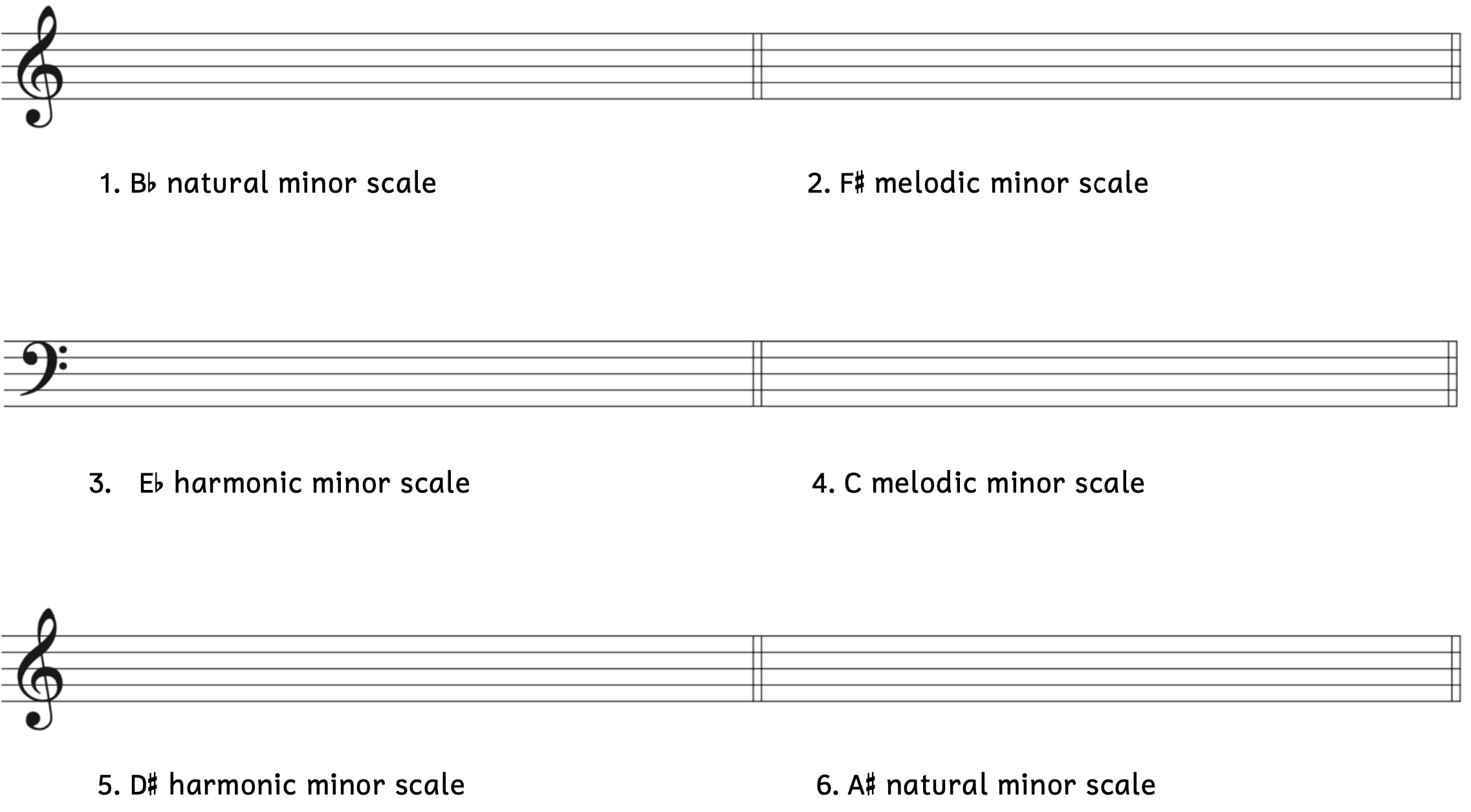

Practice 6.10D. Writing the Three Minor Scales Without a Key Signature

Directions:

- Construct the following ascending minor scales on the staff using whole notes.

- Use accidentals; do not use a key signature.

- Do not add a time signature.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 6.10E. Writing the Three Minor Scales with a Key Signature

Directions:

- Write the key signature for the given keys.

- Construct the following ascending minor scales on the staff using whole notes.

- Do not add a time signature.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

6.11 TRANSPOSITION: MODAL

At the start of this chapter, we began with a familiar tune (“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”) but with a few added accidentals, which changed the entire mood of the song to “Dingy, Dingy, Little Star.” By doing so, we used modal transposition, which refers to changing the mode from major to minor (or vice versa).

There is only one scale degree number that is unique in minor at all times: ![]() . The other two scale degrees that are lowered in minor (

. The other two scale degrees that are lowered in minor (![]() and

and ![]() ) are only lowered when they are not ascending to tonic (

) are only lowered when they are not ascending to tonic (![]() ). Otherwise, they are raised as they are in major.

). Otherwise, they are raised as they are in major.

Compare Examples 6.11.1A and B, which show the start of “London Bridge is Falling Down” in major and minor.

Example 6.11.1. Major to minor: “London Bridge is Falling Down”

A. In major

B. In minor

- In minor,

is always lowered, even if it is ascending. In the key of C major, lowered

is always lowered, even if it is ascending. In the key of C major, lowered  is E

is E .

. - In Example 6.11.1B,

is also lowered because it is not rising up to

is also lowered because it is not rising up to  . Instead,

. Instead,  returns back to

returns back to  , so it is lowered as it is found in the natural minor scale.

, so it is lowered as it is found in the natural minor scale.

Now compare Examples 6.11.2A and B, which show the start of “Joy to the World” in major and minor.

Example 6.11.2. Major to minor: “Joy to the World”

A. In major

B. In minor

- Example 6.11.2A:

- Since “Joy to the World” is in G major, there are no added accidentals.

- Example 6.11.2B:

- In minor,

is always lowered. In the key of G major, lowered

is always lowered. In the key of G major, lowered  is B

is B .

. - In measure 1,

and

and  are lowered because they are descending. F(

are lowered because they are descending. F( ) and E

) and E belong to the natural minor scale (or the descending melodic minor scale).

belong to the natural minor scale (or the descending melodic minor scale). - In measure 3,

and

and  are raised because the line is rising up to

are raised because the line is rising up to  . The notes in measure 3 belong to the ascending melodic minor scale.

. The notes in measure 3 belong to the ascending melodic minor scale. - The accidentals are courtesy accidentals: they are not required because the key signature already gives us this information, but are used as confirmation.

- In minor,

Alternatively, for modal transposition, you can use the key signature of the parallel key. When doing so, you will use different accidentals (Example 6.11.3).

Example 6.11.3. Parallel key: “Joy to the World”

- With the key signature for G minor, no accidentals are necessary in the first two bars as the melody is simply a descending natural minor scale.

- However, in measure 3,

and

and  are raised as

are raised as  ascends to

ascends to  (sol-la-ti-do), utilizing the melodic minor scale.

(sol-la-ti-do), utilizing the melodic minor scale.

Modal Transposition From Major to Minor

- Always lower

.

. - Lower

and

and  if they are descending.

if they are descending. - Do not lower

and

and  if they are ascending.

if they are ascending.

Practice 6.11A. Transposing from Major to Minor

Directions:

- Add accidentals to transpose the following example into minor.

- Begin by writing the key, adding scale degree numbers, and taking note of

,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Offenbach[14], Geneviève de Brabant, Act II, Couplets des hommes d’armes

Click here to watch the tutorial.

You can also transpose music from minor to major. Rather than lowering ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , raise

, raise ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() (Example 6.11.4).

(Example 6.11.4).

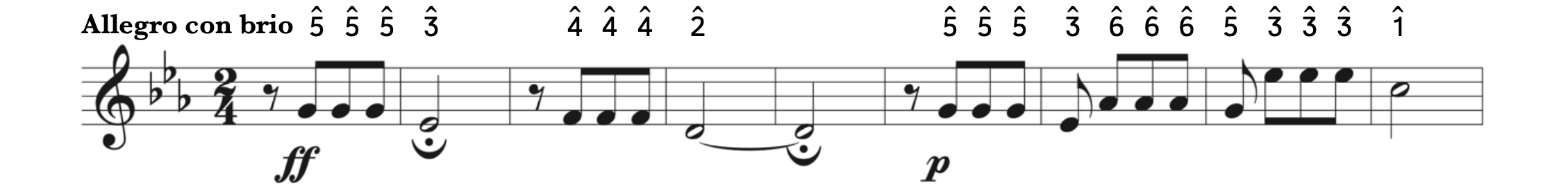

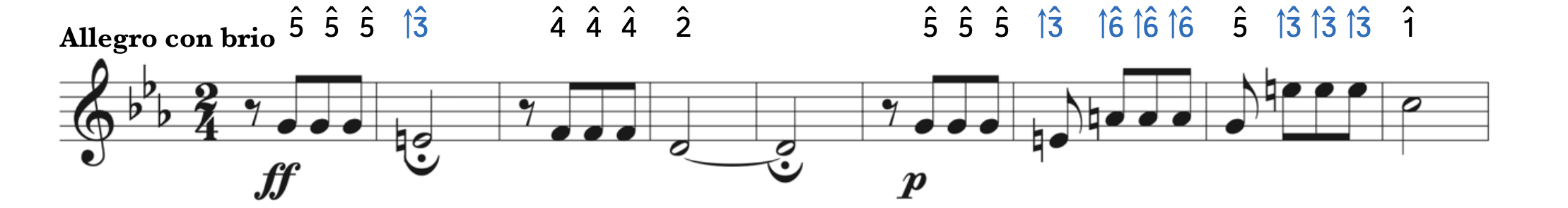

Example 6.11.4. Minor to major: Beethoven[15], Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67, i – Allegro con brio

A. In minor

B. In major

Listen to Example 6.11.4B, where every ![]() and

and ![]() are raised. Hearing such a famous tune in another mode may sound humorous and is very simple to do.

are raised. Hearing such a famous tune in another mode may sound humorous and is very simple to do.

Composers sometimes take advantage of modal transpositions. Earlier in the chapter (Example 6.5.2), we learned that the opening of Smetana’s Má Vlast was in E minor. Later in the work, Smetana transposes the melody to E major. Rather than adding multiple accidentals, he simply changes the key signature to the parallel major (Example 6.11.5).

Example 6.11.5. Parallel keys: Smetana, Má Vlast

A. In minor

B. In major

At first glance, the notes appear to be the same. However, because of the key signature, there are important differences.

Modal Transposition From Minor to Major

- Always raise

,

,  , and

, and  .

. - If

or

or  are already raised in minor, do not raise it again.

are already raised in minor, do not raise it again.

Practice 6.11B. Transposing from Minor to Major

Directions:

- Add accidentals to the opening of the Mozart symphony below to transpose it into major.

- Begin by writing the key, adding scale degree numbers, and taking note of

,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550, i – Allegro molto

Click here to watch the tutorial.

6.12 ANALYSIS

We have already practiced the steps when trying to figure out the key to a given excerpt. As music students, you will usually listen to the example while looking at it to decide the key. However, sometimes you will not be able to listen to the example. You should still be able to identify the key by following these steps.

- Look at the key signature and take note of the two choices you have with that key signature. There will be a major key and minor key.

- Look at the first lowest note, especially if it is the beginning of the piece. Does it begin on tonic (i.e.,

)?

)? - Look at the last lowest note, especially if it is the end of the piece. Does it end on tonic (i.e.,

)?

)? - Look for a raised leading tone. If the example is in minor and has

, it should be raised unless it is descending.

, it should be raised unless it is descending.

Let’s use these steps to determine the key for two examples. Do not listen to the examples first.

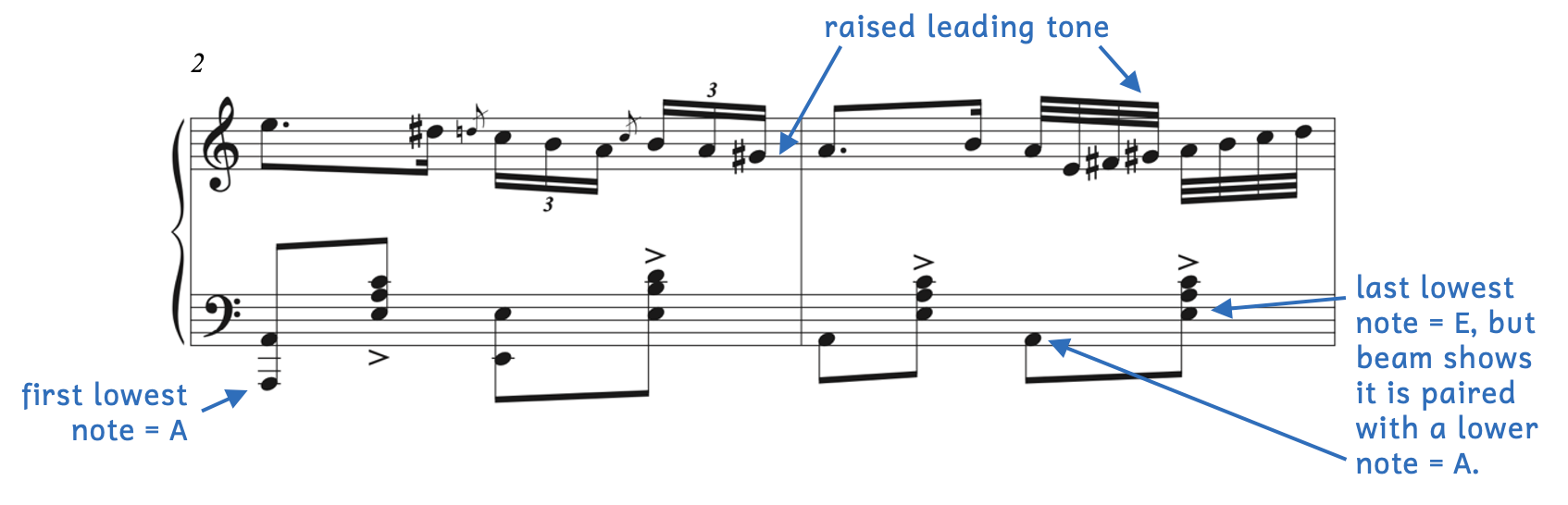

Example 6.12. Determining the key: Blahetka[16], Variations brillantes sur un thême hongrois, Op. 18

A. Introduction

B. Theme

- Example 6.12A:

- The key signature gives us two options: C major or A minor.

- The example is the start of the movement and the first lowest note is C.

- The last lowest note is C, so this example may be in C major. However, this is not the end of the movement.

- If this example were in A minor, we would see the raised leading tone, or G

. G appears numerous times, but is never raised.

. G appears numerous times, but is never raised. - In conclusion, this example is in C major.

- Example 6.12B:

- The key signature gives us two options: C major or A minor.

- The first lowest note is A. However, this is not the first bar of the movement.

- The last lowest note is E, which is not C or A. However, when we look at the E, we see that it is beamed to a lower note that falls on a strong beat, A. Therefore, we can say that the excerpt ends on A.

- If this example were in A minor, we would come across the raised leading tone, or G

. There are two Gs in this example, and they are both raised.

. There are two Gs in this example, and they are both raised. - In conclusion, this example is in A minor.

None of these steps to determine a key are 100% reliable on their own.

- The example may be a snippet that does not have

as the lowest note.

as the lowest note. - Later, we will encounter examples where the key signature does not match the key.

- We will come across many accidentals that are not raised leading tones.

For now, keys of musical examples will be fairly obvious. As we move through the chapters, determining the key will become more difficult.

Practice 6.12. Identifying Keys for Analysis

Directions:

- Identify the keys of the following examples as quickly as possible without listening to them. In a few sentences, explain why you chose the key.

1. Blahetka, Variations brillantes sur un thême hongrois, Op. 18, Variation 3

2. Blahetka, Variations brillantes sur un thême hongrois, Op. 18, Coda

Click here to watch the tutorial.

SUMMARY

-

-

- In addition to the major mode, the minor mode is the most common mode we will be studying. [6.1]

- Although there is only one type of major scale, there are three types of minor scales. A natural minor scale is made of the following diatonic steps in ascending order: whole – half – whole – whole – half – whole – whole. [6.2]

- Minor key signatures are based on the accidentals created by the natural minor scale. [6.2]

- Minor keys share the same key signature as their relative major. To find the relative major, count three steps up and match the accidentals. [6.3, 6.4, 6.5]

- The circle of fifths is a diagram that shows the relationship between keys. [6.6]

- Moving clockwise, the key ascends by five and adds a sharp.

- Moving counterclockwise, the key descends by five and adds a flat.

- Although three notes are lowered in the natural minor scale, only one has a different scale degree name: the subtonic (

). [6.7]

). [6.7] - Parallel keys share the same tonic but differ by three accidentals. [6.8]

- The harmonic minor scale begins with a natural minor scale, then raises

to become the leading tone. [6.9]

to become the leading tone. [6.9] - The melodic minor scale begins with a natural minor scale, then raises

and

and  on the way up, and returns back to the natural minor scale on the way down. [6.10]

on the way up, and returns back to the natural minor scale on the way down. [6.10] - You can make any major tune into minor by modal transposition: always lower

, and lower

, and lower  and

and  when they are descending. [6.11]

when they are descending. [6.11] - When analyzing music, you must always determine the key. There are several shortcuts you can use to help you identify the key. [6.12]

-

TERMS

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) was a Russian composer. ↵

- Georges Bizet (1838-1875) was a French composer. ↵

- Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836) was a French composer. ↵

- This author discourages counting half steps because it is time consuming and students often make errors. However, since some students use this method, it is explained here. ↵

- Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) was a Czech composer. ↵

- Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831) was a Polish composer and pianist. ↵

- Hélène Liebmann née Riese (1795-1869) was a German composer and pianist. ↵

- Katerina Veronika Anna Dusíková (1769-1833) was a Bohemian composer. ↵

- Maria Verspermann Görres Arndts (1823-1882) was a German composer who used the pseudonym “Carl Pauss.” ↵

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was an Austrian composer. ↵

- Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer. ↵

- Loïsa Puget (1810-1889) was a French composer. ↵

- Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896) was a German composer and pianist. Her husband, Robert Schumann, was also a composer. ↵

- Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) was a French composer. ↵

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was a German composer. ↵

- Leopoldine Blahetka (1809-1885) was an Austrian pianist and composer. ↵

Mode that is often associated with sad music; based on the natural minor scale.

Scale with the pattern whwwhww; minor keys are based on their natural minor scales

Minor mode + tonal center

Major and minor keys that share the same key signature.

Whole step below tonic; ^7 in minor only.

Major and minor keys that share the same tonic.

Type of minor scale with raised subtonic (i.e., leading tone instead of subtonic)

Type of minor scale where ^6 and ^7 are raised while ascending, and return to the natural minor scale when descending; the ascending and descending melodic minor scales are different

Changing pitches by changing the mode from major or minor (or vice versa)