1 The Basics I: Notes and Rests

To understand music, we start with the basics: rhythm and pitch.

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The first step in learning music is to understand the basics: rhythm and pitches.

Rhythm refers to the way musical sounds are perceived as points in time. Notes represent musical sound and rests represent silence. Notes and rests can have different values, meaning they can be longer or shorter.

Pitches refer to how musical sounds are heard in terms of how high or low they sound. Because of their close connection, the terms “pitch” and “note” are often used interchangeably. Pitches are represented by note names using the musical alphabet: A B C D E F G. After G, we return to A: A B C D E F G A B C… The first and second A are an octave apart because they are eight notes apart. B and B are also an octave apart, and this pattern continues.

This chapter will alternate between note values and note names, reinforcing each as we move forward.

1.2 NOTE VALUES

To determine the duration of pitches, we need to notate rhythm using different note values. First, we will describe the parts of a note.

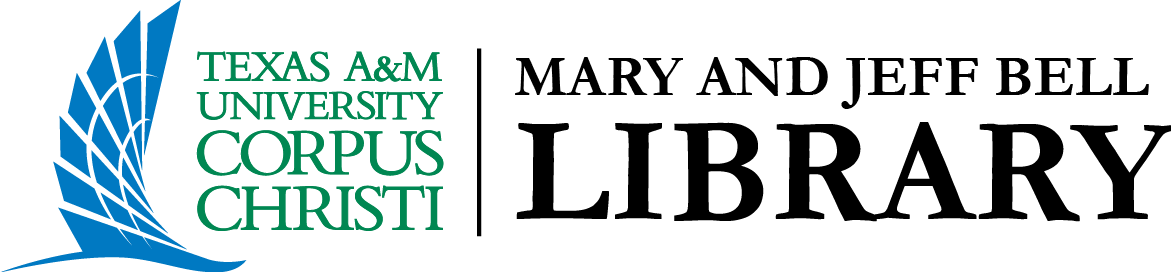

Example 1.2.1. Parts of a note

- Notehead: Each note has an oval-shaped notehead that can be unfilled or filled.

- Stem: Most noteheads (but not all) have a stem.

- When the stem points up, it is placed on the right of the notehead.

- When the stem points down, it is placed on the left of the notehead.

- Flag: Many stems (but not all) have a flag.

- Whether the stem points up or down, flags are always on the right side of the stem.

- Stems can have multiple flags. To accommodate three or more flags, the stem is lengthened.

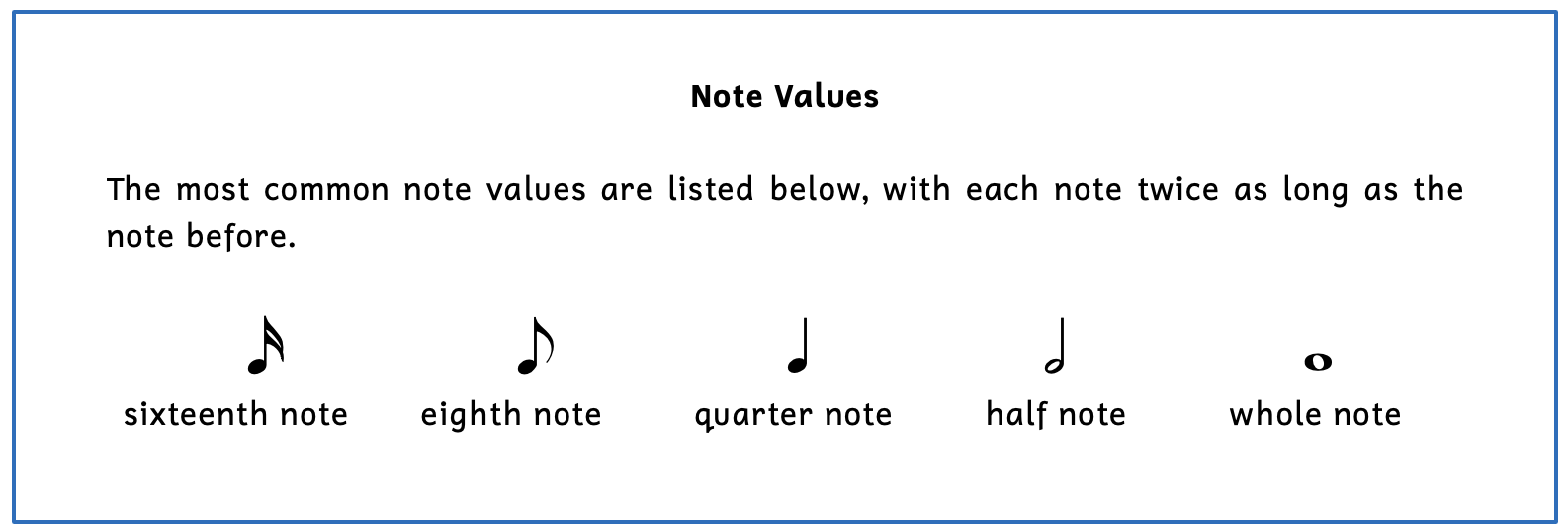

Now that we understand the basic parts of a note, we will learn about the most common types of notes.

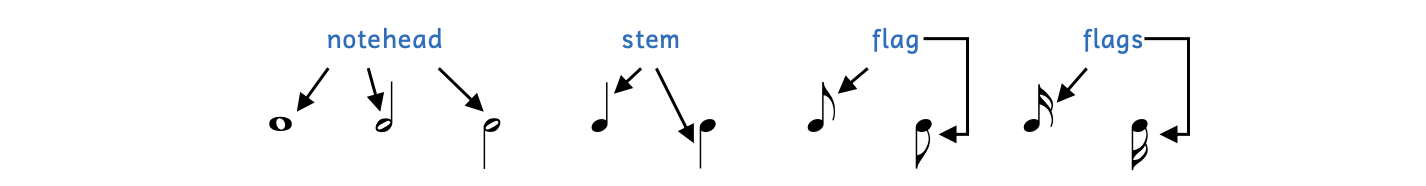

Example 1.2.2. Note types

- Whole note: Unfilled notehead without a stem

- Half note: Unfilled notehead with a stem

- Stems can point either up or down. This applies to all note values with stems.

- Quarter note: Filled notehead with a stem

- Eighth note: Filled notehead with a stem and a flag

- Sixteenth note: Filled notehead with a stem and two flags

In Example 1.2.2, the whole note has the longest duration, while the sixteenth note has the shortest duration. Each note value is proportionately related to one another. Understanding basic math and fractions helps to see how note values are connected.

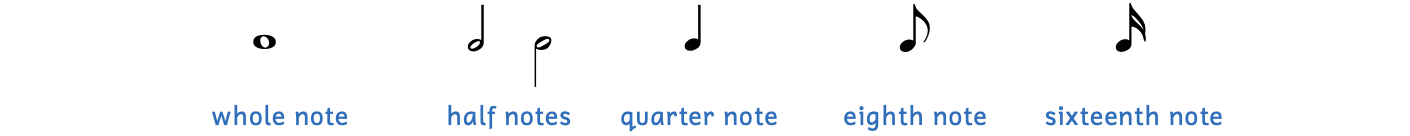

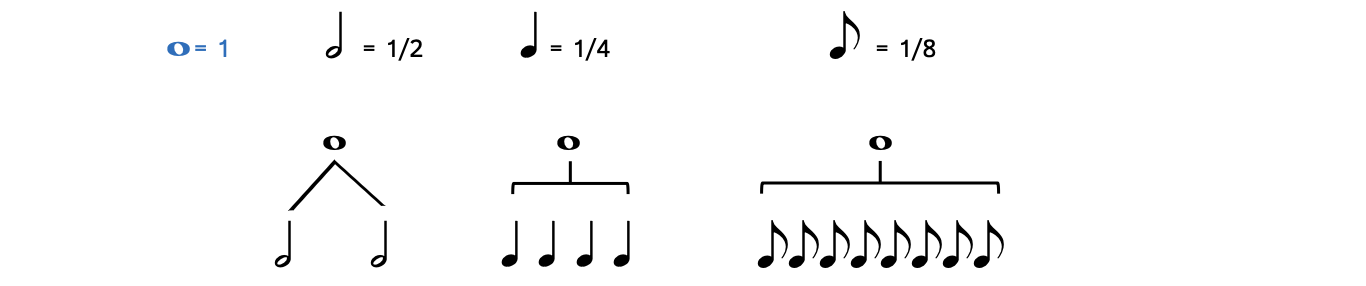

Example 1.2.3. Note values

- A whole note divides equally into two half notes.

- Since two half notes equal one whole note, one half note is equal to half the value of a whole note.

- A half note divides equally into two quarter notes.

- Since two quarter notes equal one half note, one quarter note is equal to half the value of a half note.

- A quarter note divides equally into two eighth notes.

- Since two eighth notes equal one quarter note, one eighth note is equal to half the value of a quarter note.

- An eighth note divides equally into two sixteenth notes.

- Since two sixteenth notes equal one eighth note, one sixteenth note is equal to half the value of an eighth note.

There are less-common note values that are longer or shorter than the ones listed in Example 1.2.3. Adding more flags creates notes of shorter value, including the thirty-second note, sixty-fourth note, and so on. The notes in this section are the most common ones.

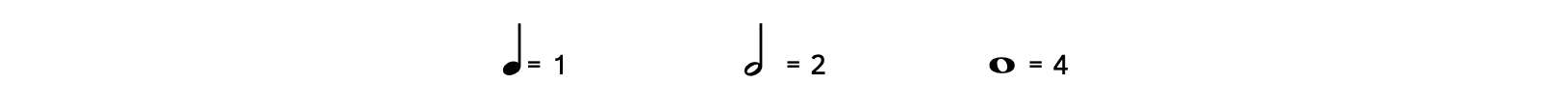

Any note can equal one. Depending on which note is equal to one, the other notes have different values. Refer to Example 1.2.4 to see note values when a whole note is equal to one.

Example 1.2.4. Whole note = 1

If a whole note is equal to one, the following statements are true:

- A whole note can be divided into two half notes, so one half note is worth half.

- A half note divides into two quarter notes and since there are two half notes in a whole note, a whole note can be divided into four quarter notes. This means that a quarter note is worth one-fourth (or one-quarter).

- Each quarter note divides into two eighth notes, resulting in eight eighth notes. Therefore, a whole note can be divided into eight eighth notes, where each eighth note is worth one-eighth.

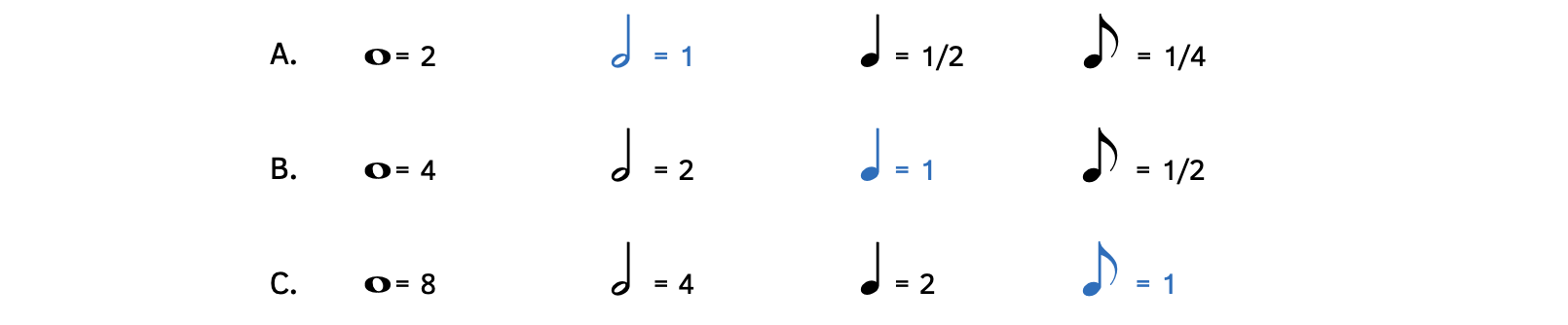

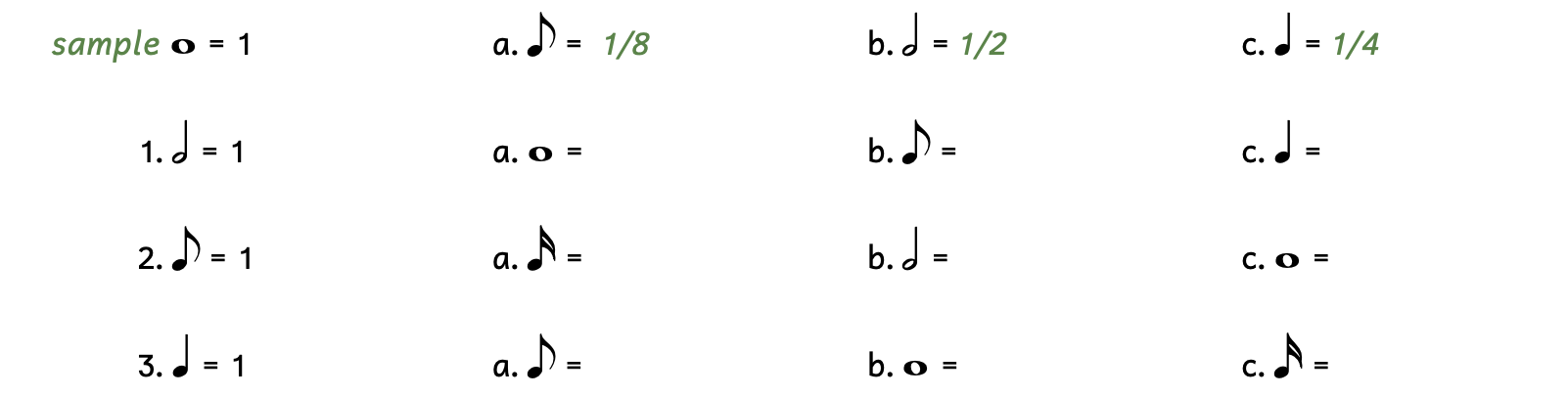

Now look at note values when other notes are equal to one in Example 1.2.5 (in blue).

Example 1.2.5. Varying note values

When a whole note was equal to one, the quarter note was worth one-fourth.

- Example 1.2.5A: When the half note is equal to one, the quarter note is worth one-half. The whole note is now equal to two.

- Example 1.2.5B: When the quarter note is equal to one, the whole note is now worth four.

- Example 1.2.5C: When the eighth note is equal to one, the quarter note is worth two and the whole note is worth eight.

If it helps, visualize note values as serving sizes of pie.

- If an entire pie (whole note) is the portion size, then eating half the pie (half note) will be worth half.

- If one-fourth of a pie (quarter note) is the portion size, then eating half the pie (half note) will be worth two servings.

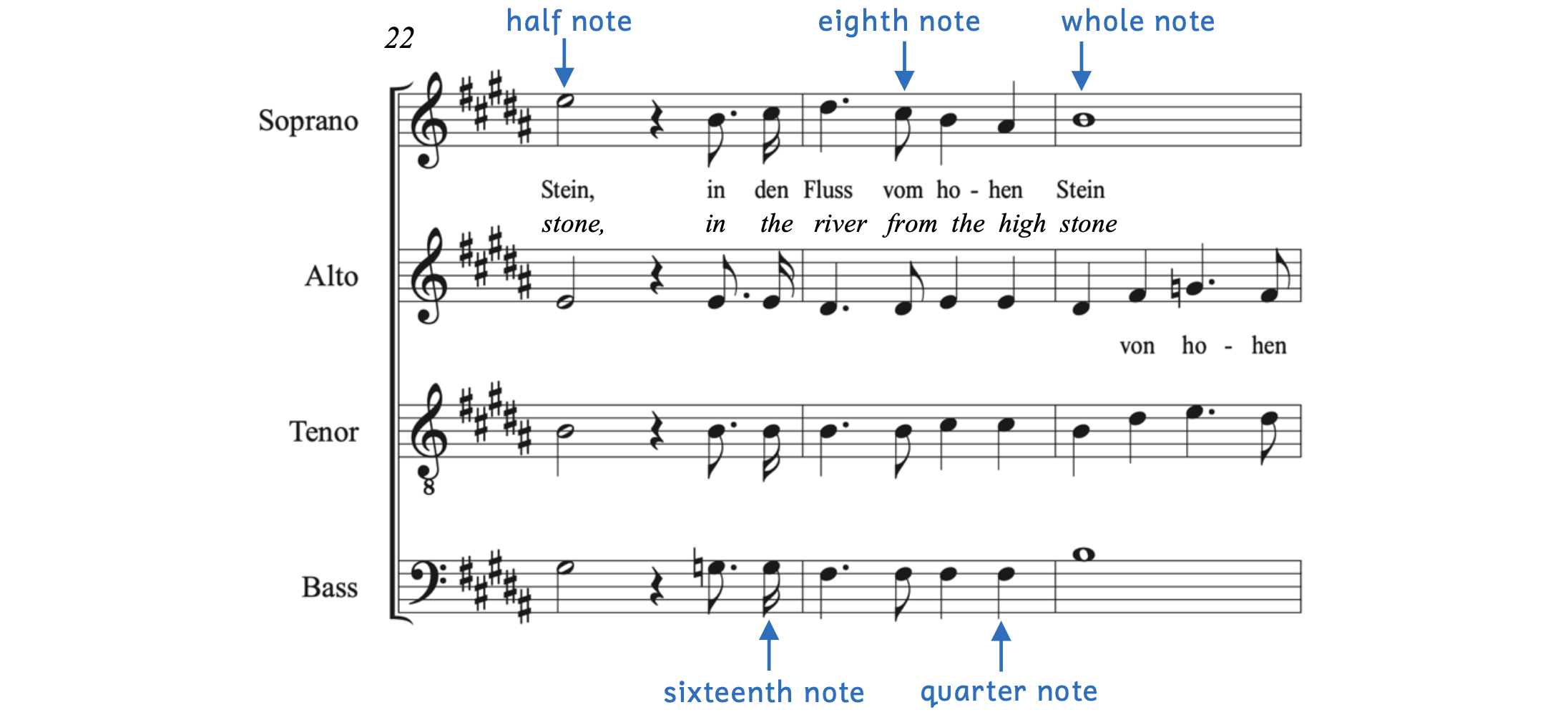

Composers often combine different note values to add variety to the music. In Example 1.2.6, Hensel uses all the notes we learned in this section. There are many more symbols you may be unfamiliar with—ignore those for now and only focus on the various note values.

Example 1.2.6. Note values: Hensel[1], “Hörst du nicht die Bäume rauschen,” Gartenlieder, Op. 3, No. 1

- Example 1.2.6 begins with half notes in all four voices.

- The stem in the alto’s half note points up and to the right of the notehead.

- The stems of the other three voices point down and to the left of the notehead.

- We will learn why some stems point up while others point down in the next section.

- The stem directions of the sixteenth notes and eighth notes vary, but the flags are always to the right.

- The other two note values we learned in this example are the quarter note and the whole note.

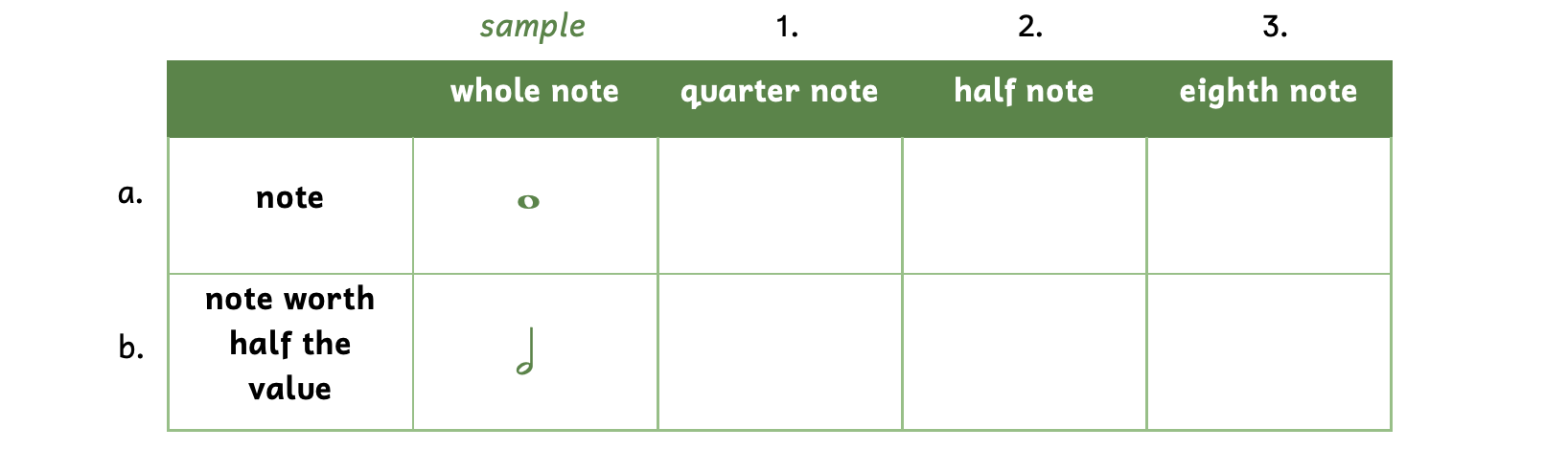

Practice 1.2A. Writing Note Values

Directions:

- Fill in the boxes with the appropriate note.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Practice 1.2B. Calculating Note Values

Directions:

- Based on the given note that equals one, calculate the value of the other notes. Use fractions instead of decimals.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

1.3 TREBLE CLEF

To determine how high or low pitches sound, we notate pitches on a musical staff with a clef.

- A musical staff (or staff) consists of five horizontal lines where notes are placed. You will be writing on staff paper for many of your assignments. Notes can be placed in the spaces between the lines or directly on the lines themselves.

- A clef is placed at the start to indicate how high or low the notes sound. There are several different types of clefs, but the staff remains consistent.

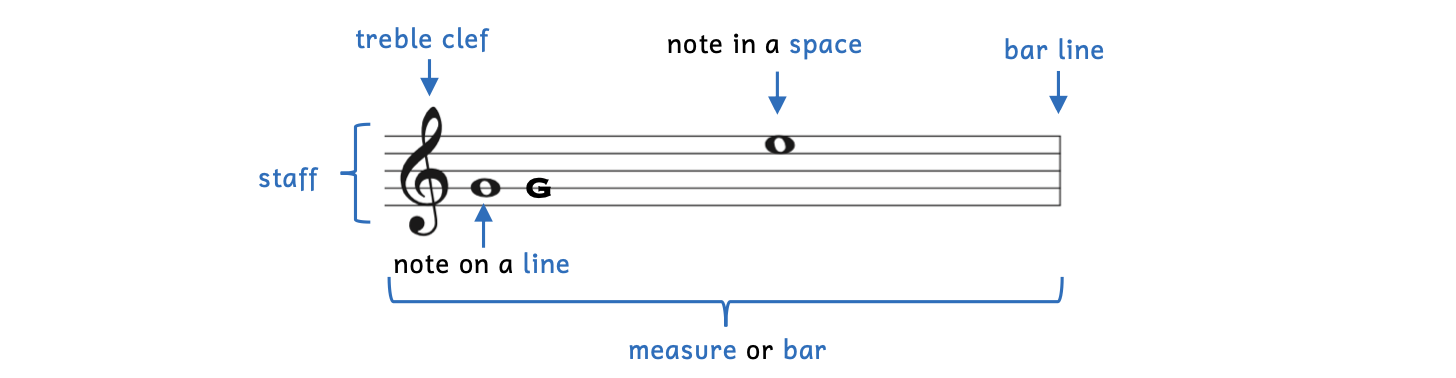

Example 1.3.1. Musical staff and treble clef

- Staff: Pitches are written on five horizontal lines called a staff.

- Notes can be written on a line.

- The whole note on the line does not fill an entire space above or below, and the line runs through the middle of the notehead.

- There are five lines in the musical staff.

- Notes can be written in a space, which is between the lines.

- The whole note in the space does not go beyond the top or bottom line and fits neatly between the lines.

- There are four spaces in the musical staff.

- Notes can also be written above or below the staff, which will be discussed in Example 1.3.3.

- Notes can be written on a line.

- Treble clef: The treble clef is a specific type of clef that is placed at the beginning of the staff and tells us how high or how low a note sounds.

- The treble clef is the most common clef for higher voices (e.g., soprano and alto) and higher-sounding instruments (e.g., flute, clarinet, oboe, trumpet, violin).

- The treble clef is also known as the G clef.

- The starting point of a treble clef (the middle of the treble clef that looks like a snail shell) falls on where the pitch G lies. (The note on a line in Example 1.3.1 is G.)

- The shape of the treble clef itself looks like the letter G.

- The treble clef is difficult to draw, so be sure to practice writing it.

- Bar line: At the end of the staff, there is a vertical line called a bar line, which breaks music into easy-to-understand segments called measures or bars.

- Notice that there is no bar line at the beginning.

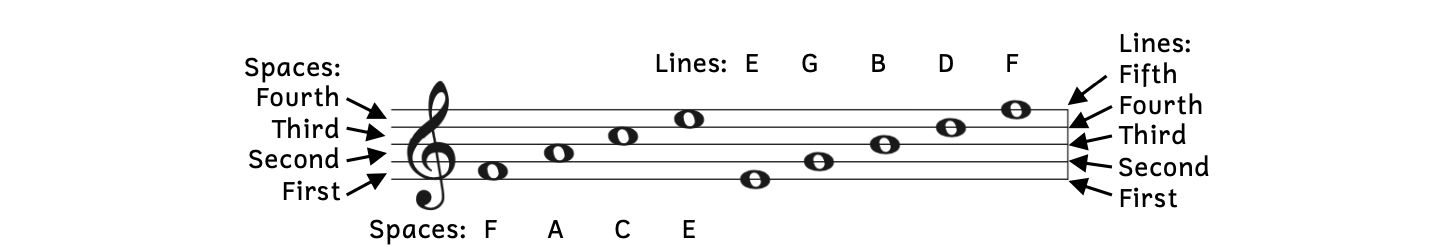

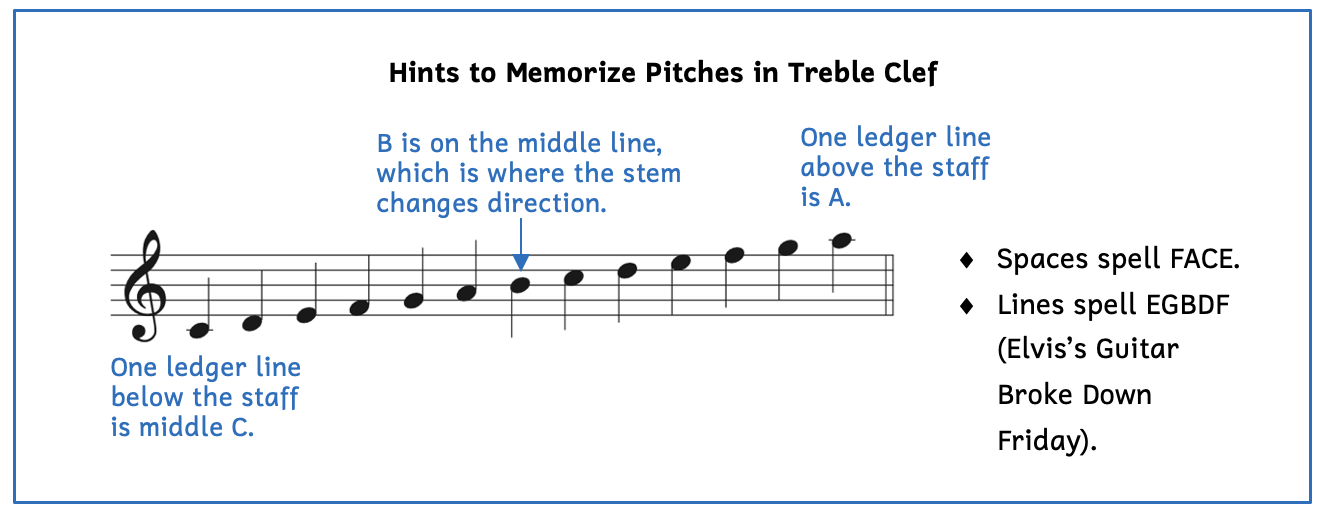

For treble clef, the pitches are set as shown in Example 1.3.2. It is extremely helpful to memorize the placement of these pitches on the staff as quickly as possible.

Example 1.3.2. Pitches in the treble clef

- Notes in the spaces of a staff with a treble clef spell FACE.

- The first space is the lowest space, while the fourth space is the highest space.

- The first space is F.

- Notes on the lines of a staff with a treble clef spell EGBDF. You can use a mnemonic device, such as Elvis’s Guitar Broke Down Friday.

- The first line is the lowest line, while the fifth line is the highest line.

- The fifth line is F. The first space’s F and the fifth line’s F are an octave apart.

Although mnemonic devices such as Elvis’s Guitar Broke Down Friday can help you at first, it is extremely important that you memorize how to read notes quickly. There are numerous apps and websites that can help you with fluency.

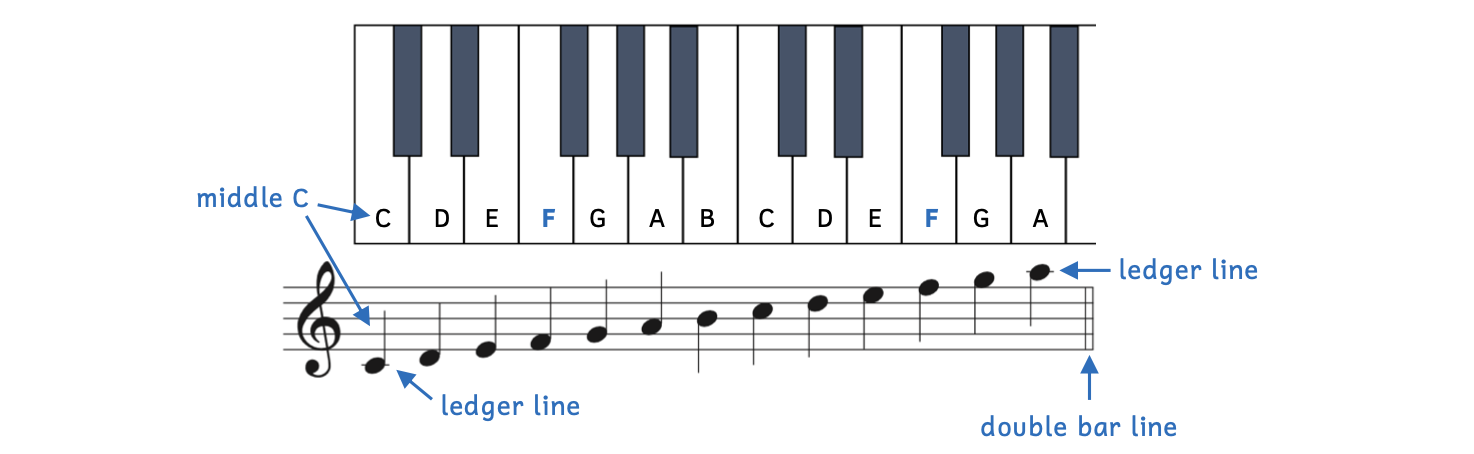

In addition to the notes in Example 1.3.2, you should be fluent with a few extra notes below and above the staff. We can use a piano keyboard to help us.

Example 1.3.3. Keyboard and treble clef

The white keys on the piano keyboard follow the musical alphabet, while the notes on the staff alternate between notes on a line and notes in a space. Remember that stems can point up or down. Notice how the stems are pointed in Example 1.3.3.

- Noteheads on the second space and below have stems that point up and to the right.

- Noteheads on the third line and above have stems that point down and to the left.

- Stems are one octave in length. Locate the two Fs (in blue on the keyboard), which are an octave apart.

- The stem on the F in the first space extends up to where the F on the fifth line is, making the stem an octave in length.

- The stem on the F on the fifth line extends down to where the F in the first space is.

Notice the terms in blue in Example 1.3.3:

- When we go beyond the staff, we need to add a ledger line, because there are no more lines to tell us what the note is.

- A ledger line is a short line that represents a line on the staff if the staff were to continue (down or up) beyond its five lines. Without ledger lines, notes beyond the staff would just be floating in space.

- Look at the last A, which has a ledger line. Without the ledger line, we would not be sure if the note was A or G.

- Middle C has a ledger line and is the lowest note shown.

- Middle C sits approximately halfway on a piano keyboard and is often used to give a visual sense of location. For example, one could say, “It’s the F right above middle C.”

- If we need to go even higher than the last A or even lower than the first C, we would add more ledger lines.

- The double bar line is a specific type of bar line that has two closely-placed vertical lines next to each other.

- The double bar line is used when the next measure does not relate to the previous measure, when there are certain changes between one measure to the next, or when the next measure begins something new. (We will learn more about this later.)

The collection of notes in Example 1.3.3 is what you should be able to write and recognize fluently. Before moving on, be sure that you can identify and write these notes at approximately one per second.

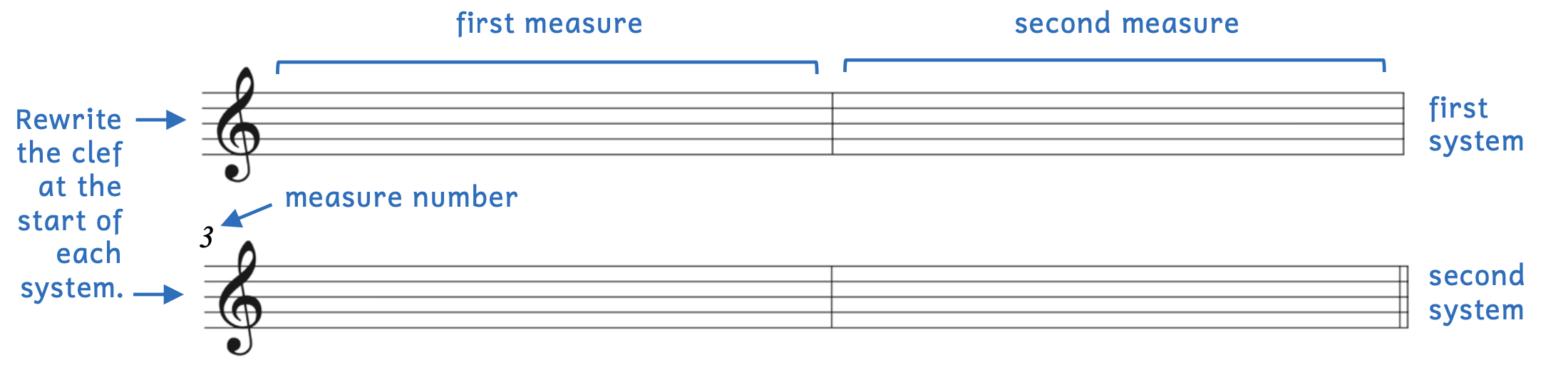

Each row of staff, called a system, begins with a clef. Make sure to rewrite the clef when you begin a new system.

Example 1.3.4. Systems

- The treble clef is written at the start of each staff.

- The first line of music is called the first system, while the second line of music is called the second system.

- Every system must end with a bar line if the measure is complete.

- When we begin the second system, we notate the measure number (or bar number) on the top left-hand corner of the staff.

- When writing, use “m.” to abbreviate the measure number. For example, “The second system begins at m. 3.”

- When referring to multiple measure numbers, “mm.” is the abbreviation for measures: “The second system consists of mm. 3-4.”

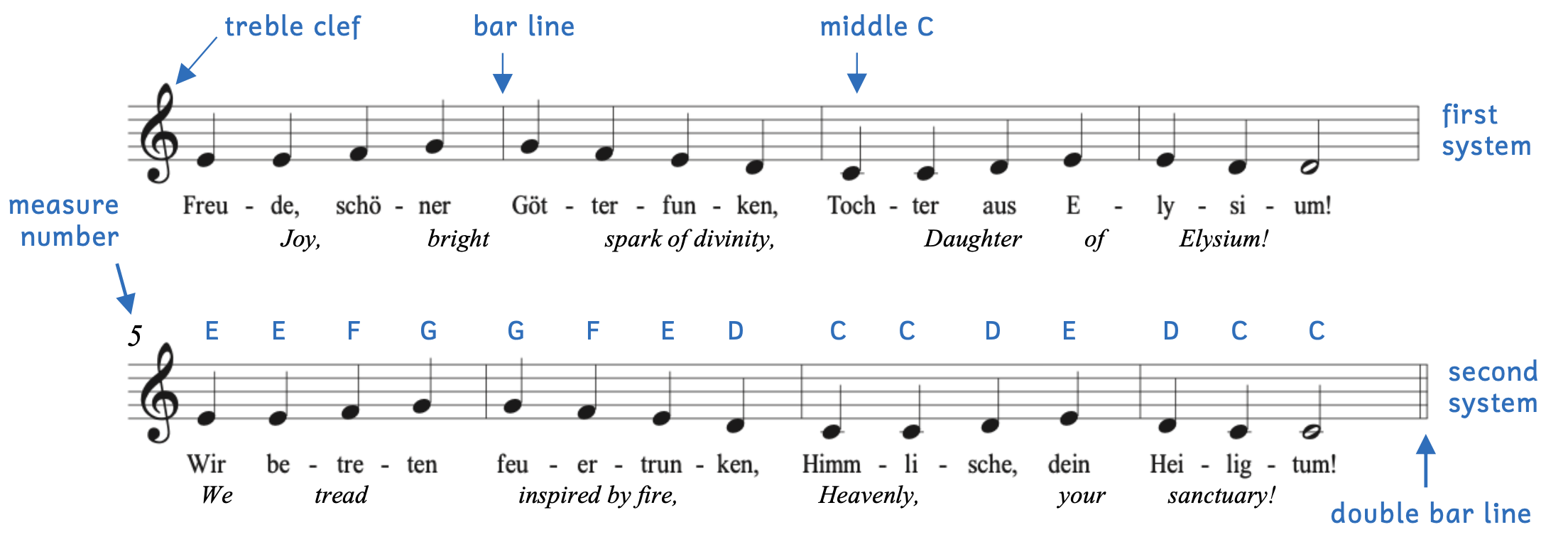

Example 1.3.5 comes from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. See how many familiar musical terms you can already identify in this excerpt. The English translation is beneath the German text and the pitches are given above the music in the second system.

Example 1.3.5. Treble clef: Beethoven[2], Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125, iv, “Ode to Joy”

- Both the first and second system begin with a treble clef.

- Bar lines separate each measure and the example concludes with a double bar line.

- Middle C occurs six times—can you find them all?

- The second system begins on measure 5, which is labeled on the top left-hand corner of the staff.

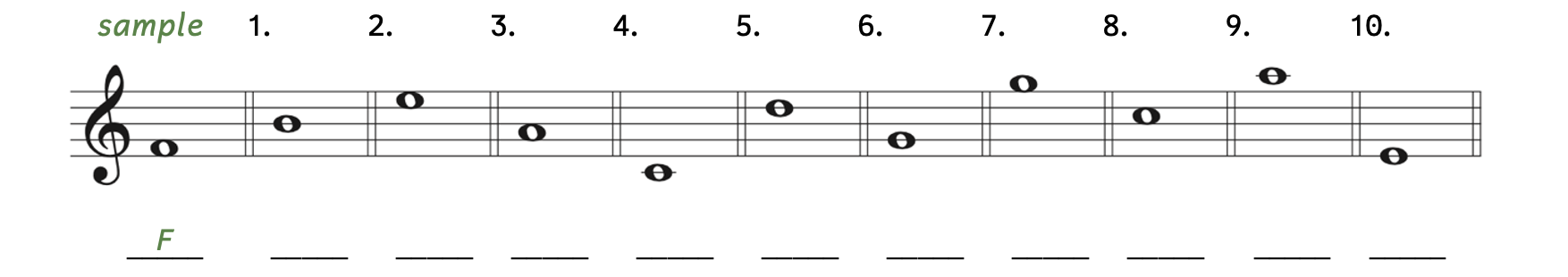

Practice 1.3A. Identifying Pitches in the Treble Clef

Directions:

- Identify the pitches on the staff. Try to identify the pitches as quickly as possible and without aids.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

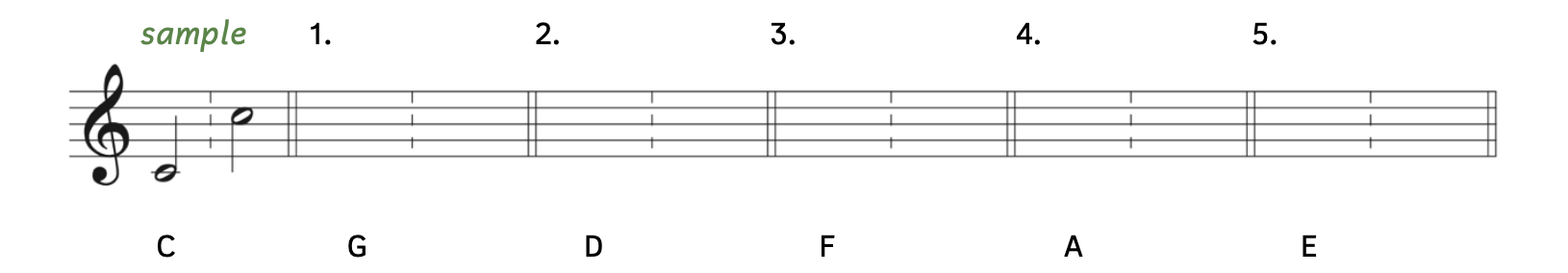

Practice 1.3B. Writing Pitches in the Treble Clef

Directions:

-

- Write the pitches on the staff using half notes. Each note should have two answers (a low version and a high version). Try to write pitches as quickly as possible and without aids.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

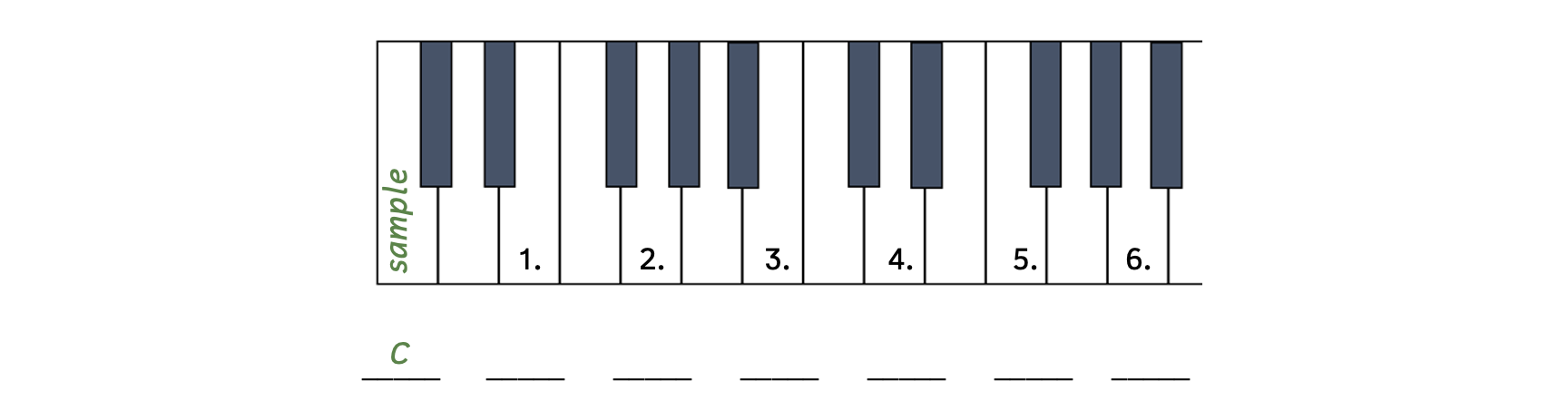

Practice 1.3C. Identifying Notes on the Piano Keyboard

Directions:

-

- Identify the notes on the keyboard.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

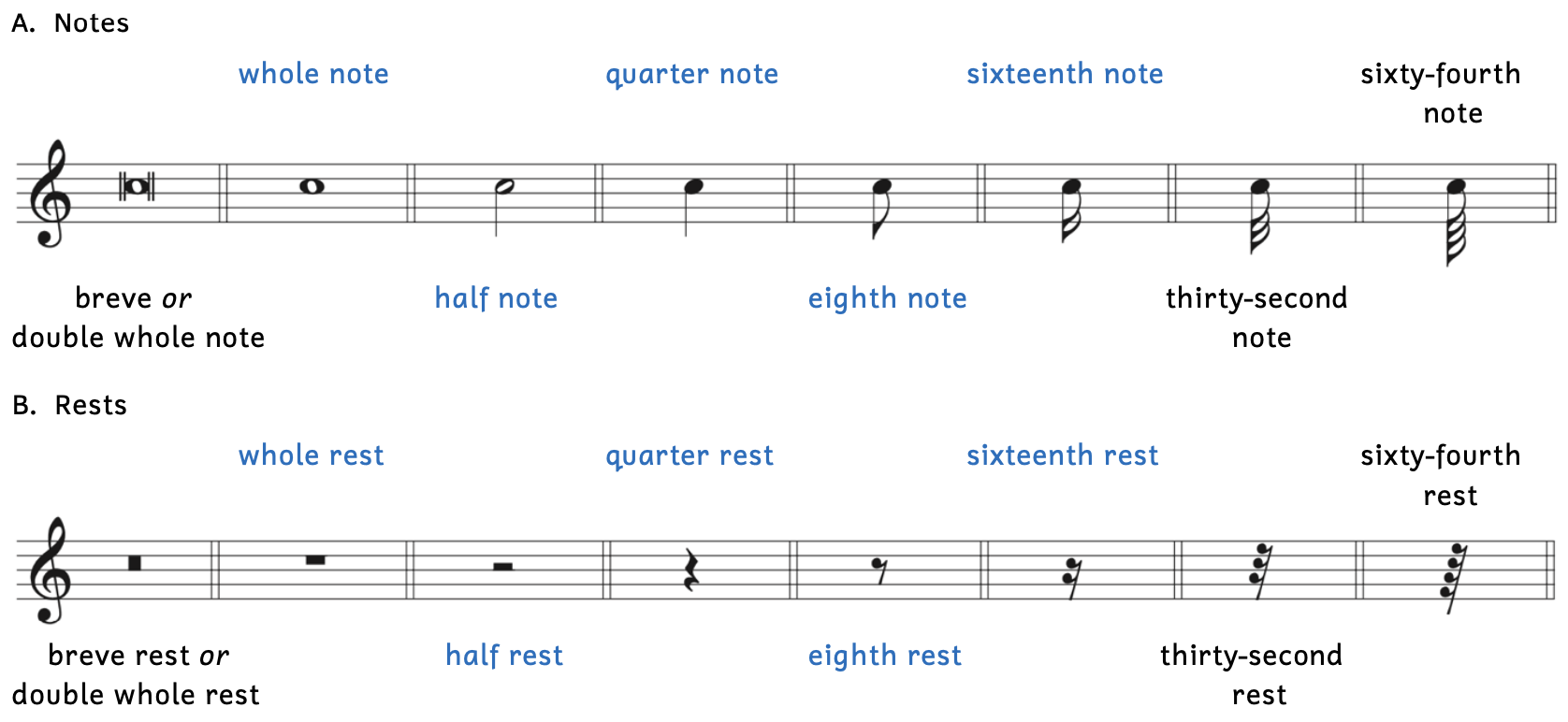

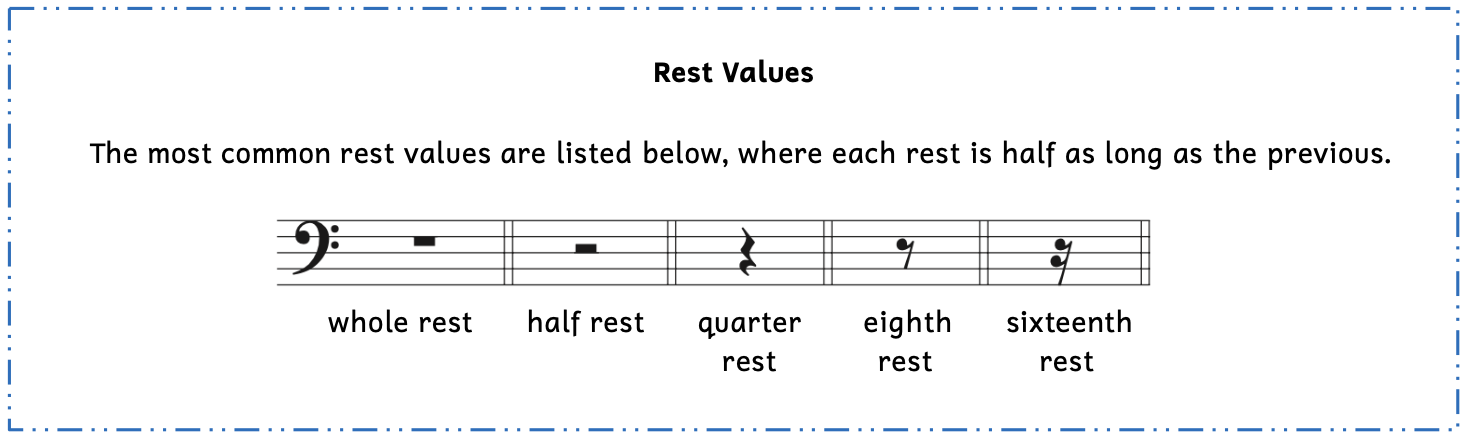

1.4 REST VALUES

In music, silence is as important as sound. Just as we use note values to represent how long to hold out sounds, we use rest values to show how long to have silence. Now that we are familiar with the basic note values, we will also learn about the less-common note values in this section. The notes and rests in blue in Example 1.4.1 are the most common ones.

Example 1.4.1. Notes and rests

First, notice a few things about the less-common notes (Example 1.4.1A, in black):

- The only note value larger than a whole note is the breve, or double whole note.

- A breve is worth twice as much as a whole note. This is not used very often.

- The thirty-second note has three flags.

- A thirty-second note is half the value of a sixteenth note.

- Because there are so many flags, the length of the stem is extended.

- The sixty-fourth note has four flags.

- A sixty-fourth note is half the value of a thirty-second note.

- Because there are even more flags, the length of the stem is extended even more.

All the rests are equivalent to the notes of the same name (Example 1.4.1B). For example, the half note and the half rest are equal in value. One major difference between notes and rests is their location on the staff. As we saw earlier, notes can move up and down the staff. Rests, however, are set.

- The breve rest (or double whole rest), whole rest, and half rest are all located in the third space.

- Students often confuse the whole rest with the half rest. Both rests reside in the third space, but the whole rest hangs down from the fourth line, while the half rest sits on the third line.

- The quarter rest sits in the middle of the staff.

- The quarter rest is difficult to draw, so be sure to practice writing it.

- The eighth rest and sixteenth rest begin in the third space and descend.

- The sixteenth rest is taller than the eighth rest.

- The third-second rest and sixty-fourth rest begin in the fourth space and descend.

- Like the thirty-second note and sixty-fourth note, the thirty-second rest and sixty-fourth rest are extended to be taller.

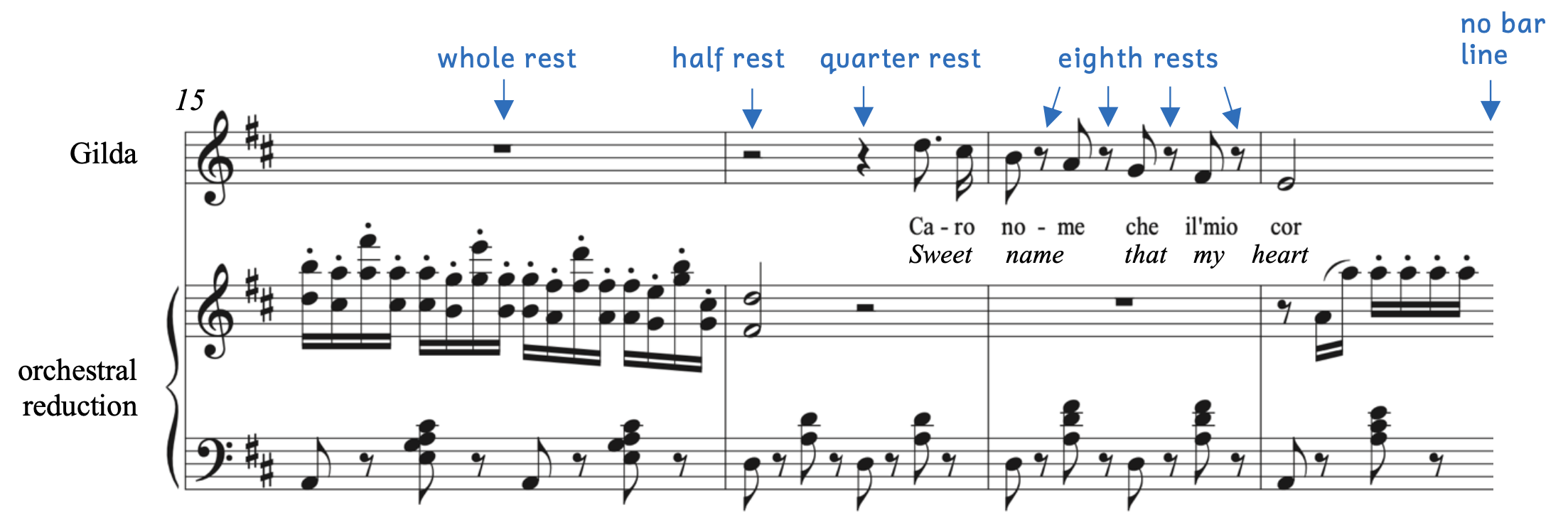

As already mentioned, silence is as important as sound in music. Listen to Example 1.4.2 and only focus on the rests in Gilda’s part. The translation appears below the Italian lyrics.

Example 1.4.2. Rests: Verdi[3], “Caro nome,” Rigoletto, Act I

- Gilda’s part begins with a whole rest while the orchestra plays.

- The soprano must be silent even longer, as there is a half rest followed by a quarter rest.

- In measure 17, eighth notes alternate with eighth rests resulting in silence between each note. Do you notice the silence between the syllables? Does the silence between notes make you interpret her words differently?

- There is no bar line at the end of this example. This is because the musical example ends before the measure ends. There is more music in this measure, but the example does not include it.

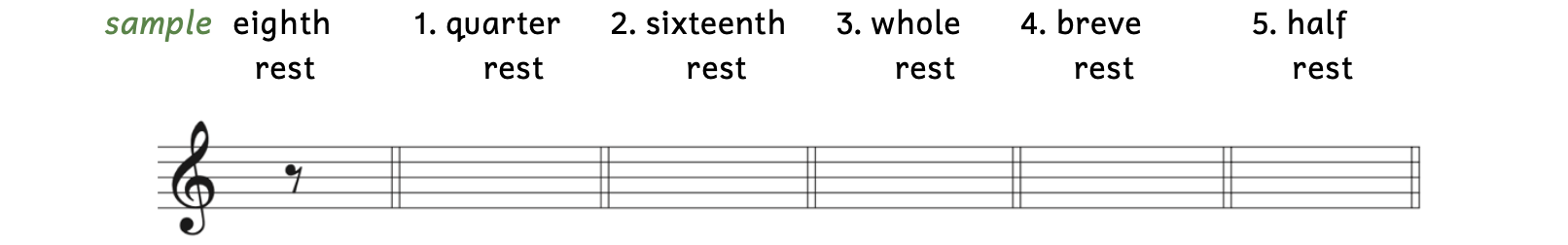

Practice 1.4A. Writing Rests

Directions:

- Write the given rests on the staff. Remember that rests must be precisely written on the staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

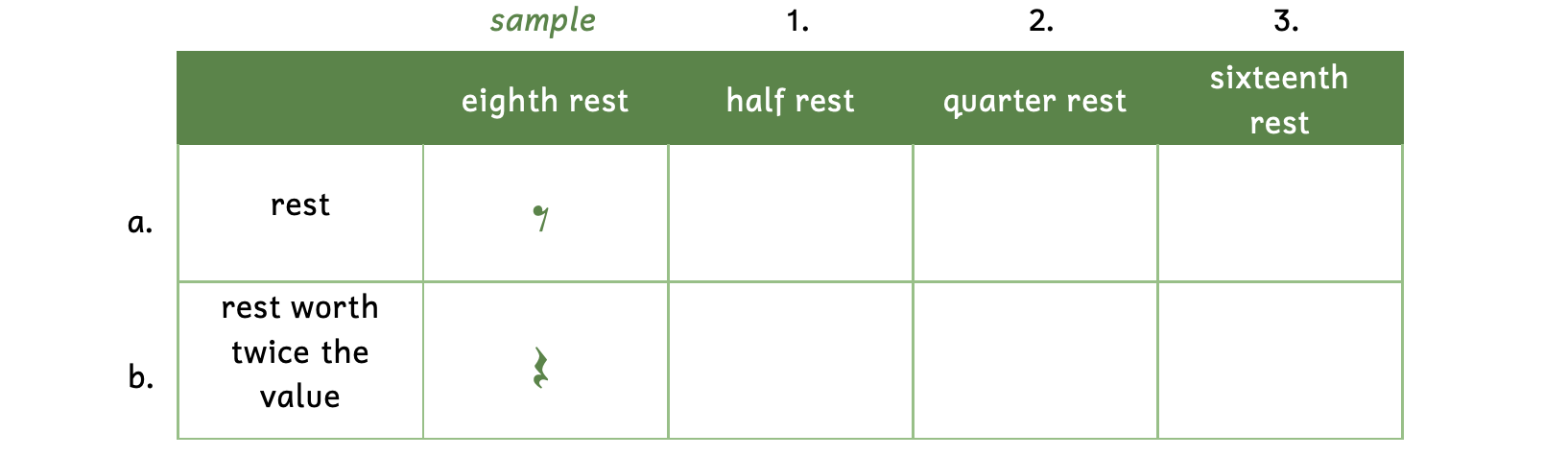

Practice 1.4B. Calculating Rests

Directions:

- Fill in the boxes with the appropriate rest.

1.5 BASS CLEF

In addition to the treble clef, the bass clef is also extremely common.

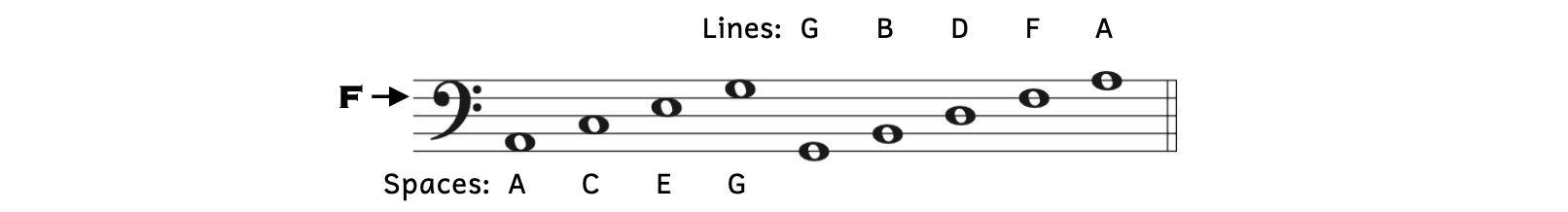

Example 1.5.1. Pitches in the bass clef

- The bass clef is the most common clef for lower voices (e.g., tenor and bass) and lower-sounding instruments (e.g., bassoon, tuba, cello).

- The bass clef is also known as the F clef.

- The starting point of a bass clef (ball part) falls on the line where the pitch F is. (The fourth line is F.)

- The two dots surround the line where F is.

- The shape of the bass clef itself looks like a cursive upper-case F.

- Notes in the spaces of a staff with a bass clef spell ACEG. You can use a mnemonic device, such as All Cows Eat Grass.

- Notes in the lines of a staff with a bass clef spell GBDFA. You can use a mnemonic device, such as Gentle Butterflies Don’t Fight Ants.

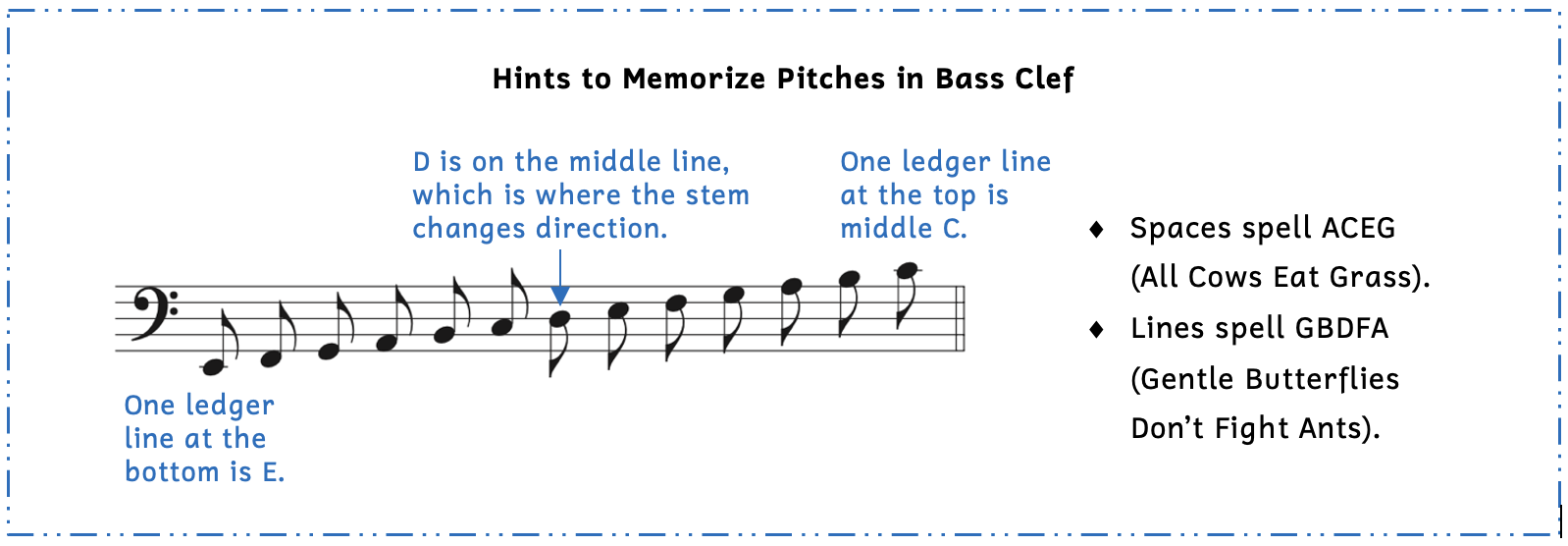

Again, although these mnemonic devices can help you at first, it is extremely important that you memorize how to read notes quickly. In addition to the notes shown above, you should be fluent with a few extra notes below and above the staff.

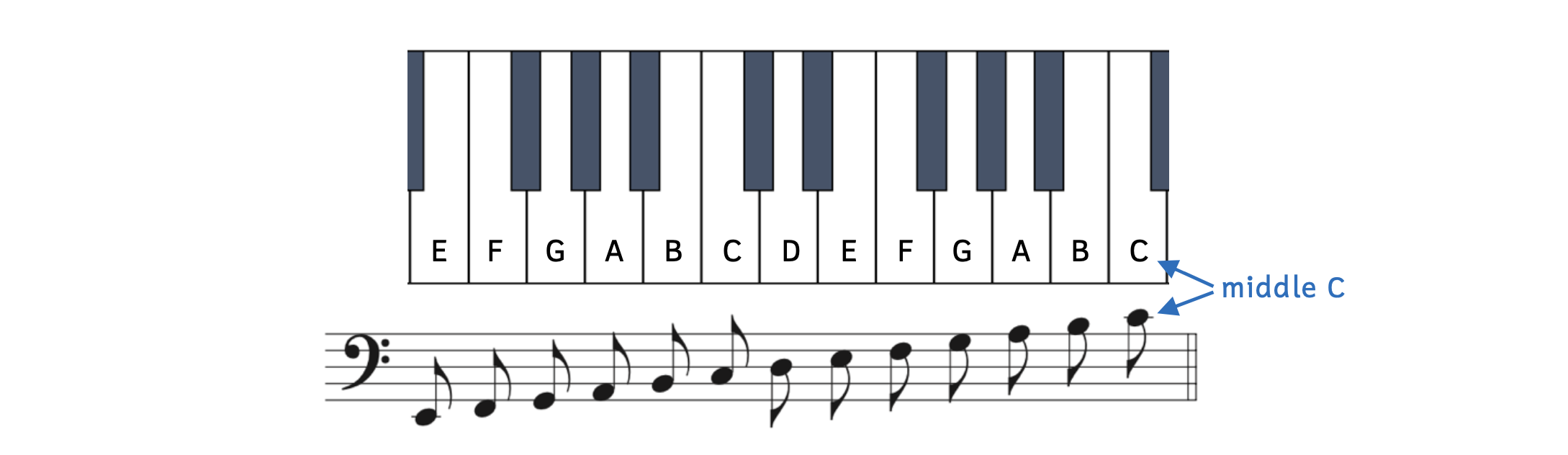

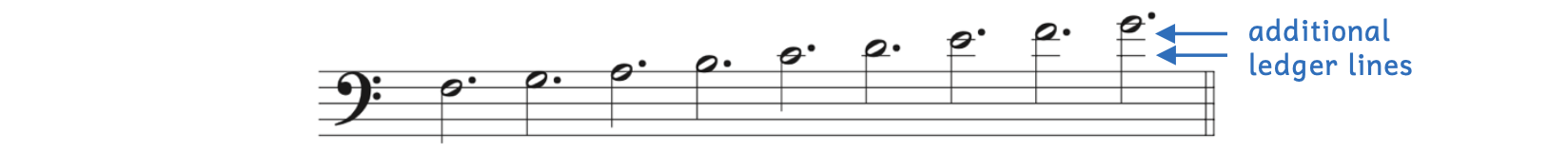

Example 1.5.2. Keyboard and bass clef

Just as with the treble clef, the white keys on the piano keyboard follow the musical alphabet, while the notes on the staff alternate between notes on a line and notes in a space. Remember that stems can point up or down, but flags are always placed on the right.

- Like the treble clef, notes in the second space and below have stems pointing up.

- Notes on the third line and above have stems pointing down.

Whereas middle C (with one ledger line) was the lowest note in Example 1.3.3. for the treble clef, middle C (with one ledger line) is now the highest note in Example 1.5.2. for the bass clef.

The collection of notes in Example 1.5.2 is what you should be able to write and recognize fluently. Before moving on, be sure that you can identify and write these notes at approximately one per second.

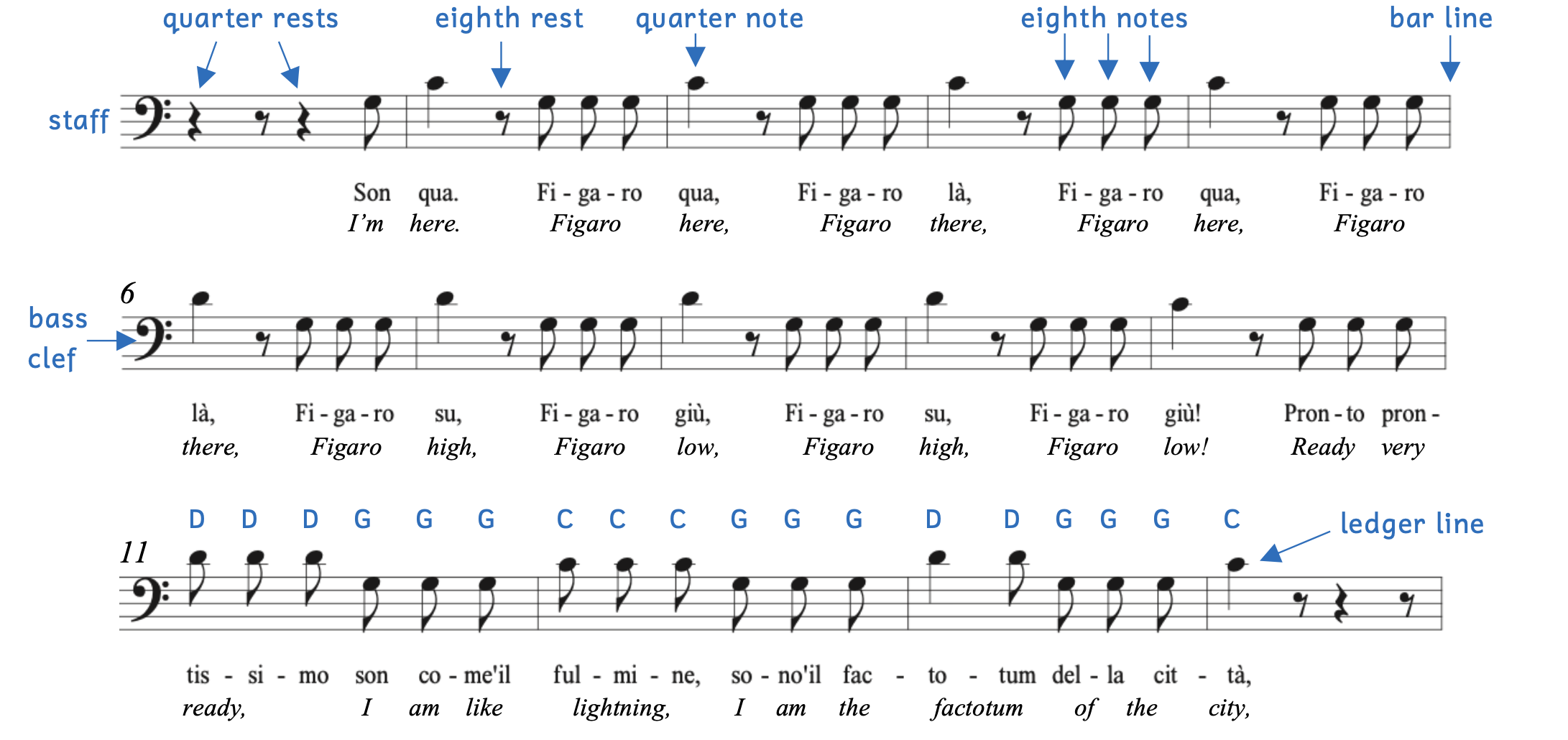

Example 1.5.3 might sound familiar to you from cartoons or commercials. The aria, “Largo al factotum,” comes from Rossini’s opera The Barber of Seville. See how many familiar musical terms you can already identify in this excerpt. The English translation is beneath the Italian text and the pitches are given above the staff in the third system.

Example 1.5.3. Bass clef: Rossini[4], “Largo al factotum della città,” The Barber of Seville, Act I

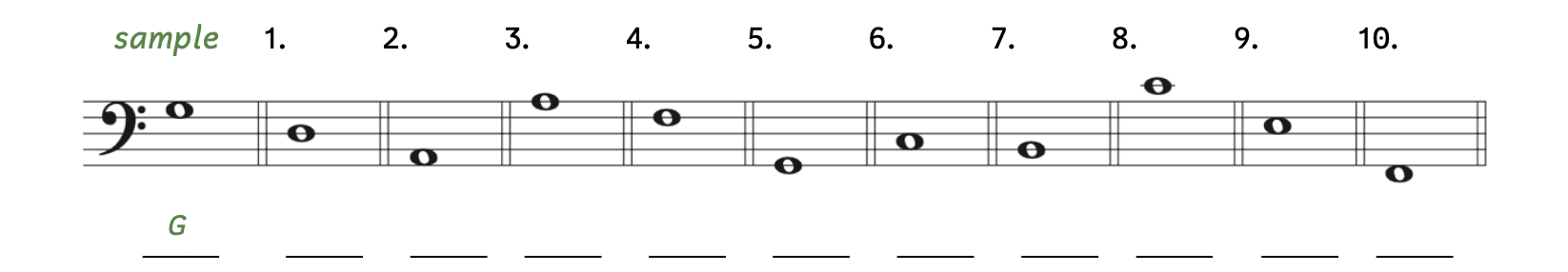

Practice 1.5A. Identifying Pitches in the Bass Clef

Directions:

- Identify the pitches on the staff. Try to identify the pitches as quickly as possible and without aids.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

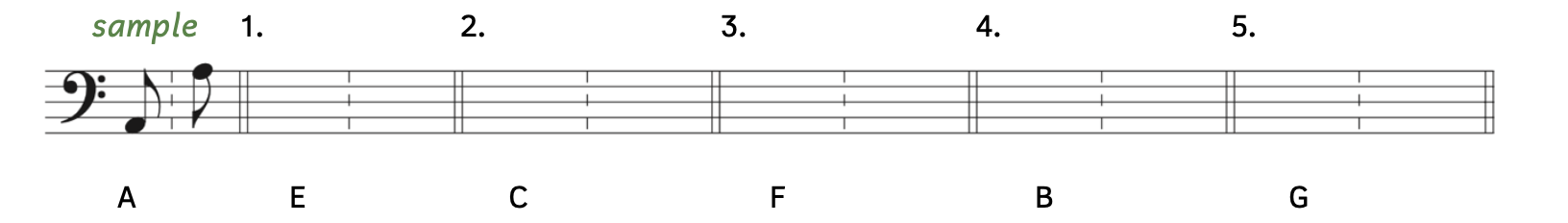

Practice 1.5B. Writing Pitches in the Bass Clef

Directions:

- Write the pitches on the staff using eighth notes. Each note should have two answers (a low version and a high version). Try to write pitches as quickly as possible and without aids.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

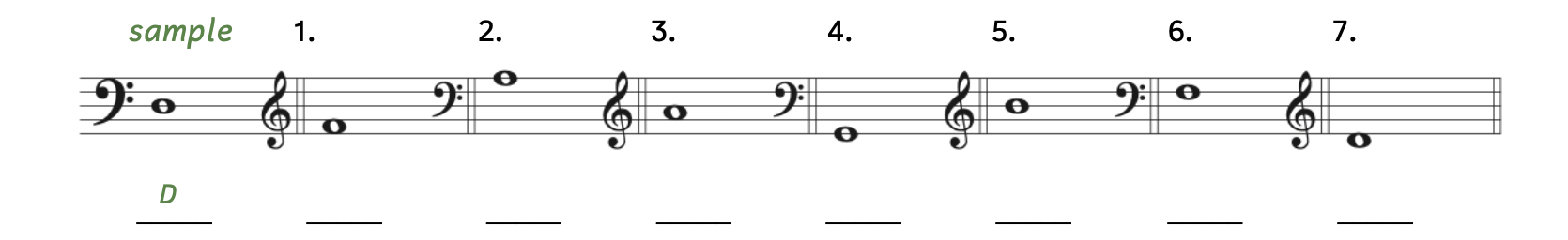

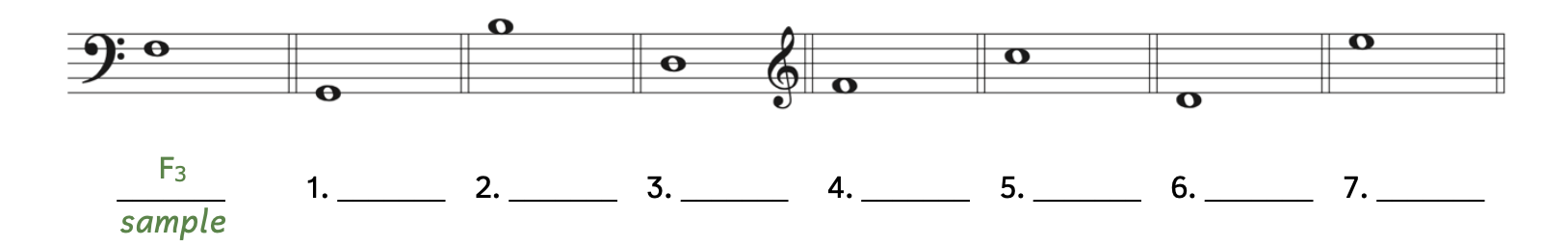

Practice 1.5C. Identifying Pitches in the Treble and Bass Clefs

Directions:

- Identify the pitches on the staff. Beware of changing clefs.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

1.6 DOTS

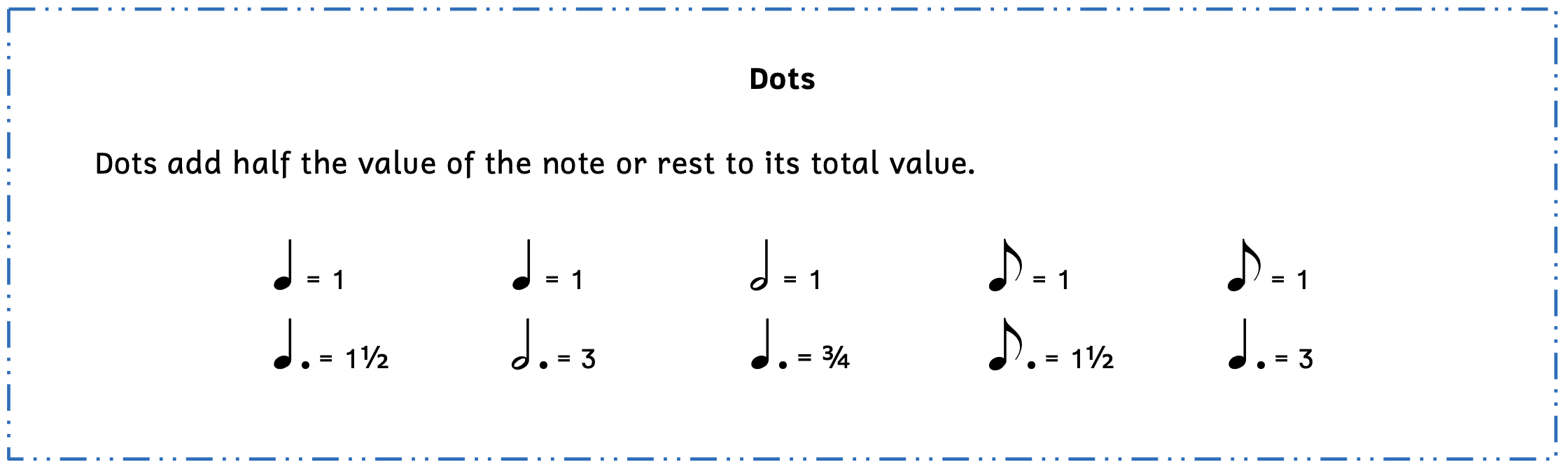

We learned that different notes can have the value of one, which makes other notes worth varying amounts.

Example 1.6.1. Note values

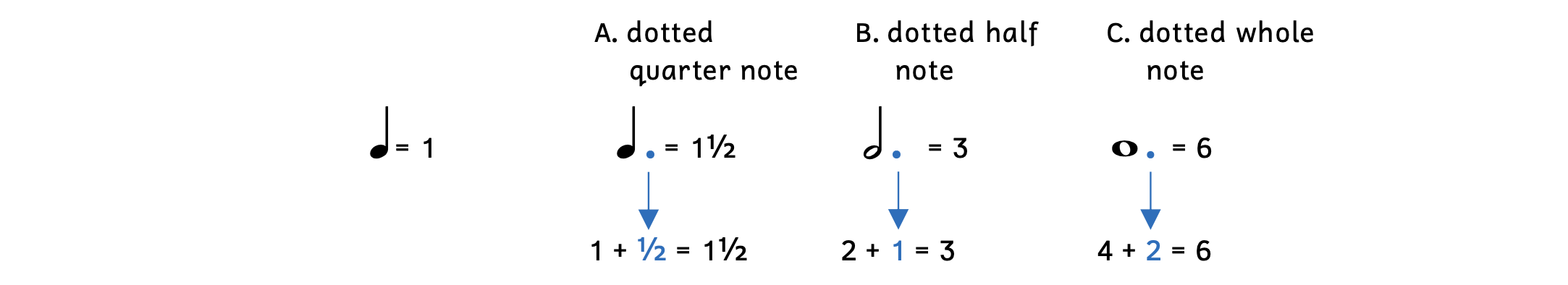

However, is there a note equal to 3? Yes, there is a note if we use an augmentation dot (or dot).

Example 1.6.2. Note value = 3

When we add a dot after any note, it becomes a dotted note adds half the value to the note. Add the word “dotted” before the name of the note. For example, a half note becomes a dotted half note. In Example 1.6.2, the dotted half note = 3.

Example 1.6.3. Dotted notes

- Example 1.6.3A: A quarter note = 1. For a dotted quarter note, the dot represent half of 1, which is ½. Therefore, 1 + ½ = 1½.

- Example 1.6.3B: If a quarter note = 1, a half note = 2. For a dotted half note, the dot represents half of 2, which is 1. Therefore, 2 + 1 = 3.

- Example 1.6.3C: If a quarter note = 1, a whole note = 4. For a dotted whole note, the dot represent half of 4, which is 2. Therefore, 4 + 2 = 6.

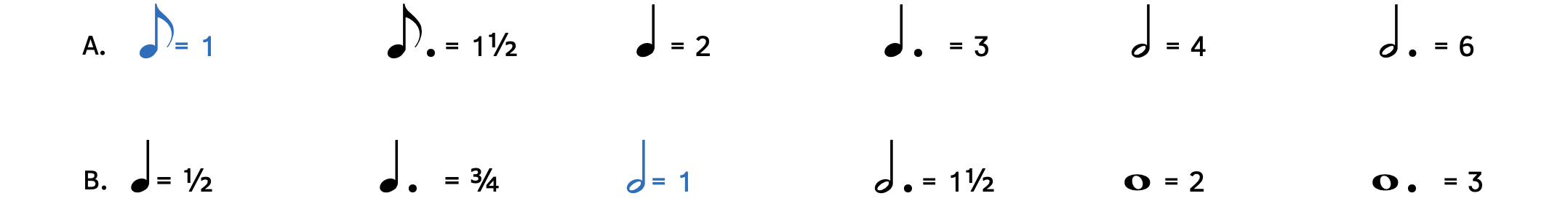

Just as with notes without dots, dotted notes vary in value depending on what type of note is equal to one. In Example 1.6.4, the notes that are equal to one are in blue.

Example 1.6.4. Varying note values

- Example 1.6.4A: If an eighth note = 1, a dotted eighth note = 1½, a dotted quarter note = 3, and a dotted half note = 6.

- Example 1.6.4B: However, if a half note = 1, a dotted quarter note = ¾, a dotted half note = 1½ and a dotted whole note = 3.

Students often struggle with note value less than one (i.e., notes that require fractions).

Example 1.6.5. Fractions

- If a half note = 1 and a half note is divided into two quarter notes, then a quarter note = ½.

- A dot adds half the value.

- If a quarter note = ½, you must find half of ½. Half of ½ is ¼.

- ½ + ¼ = ¾ (half a pie + a quarter of a pie = three-quarters of a pie)

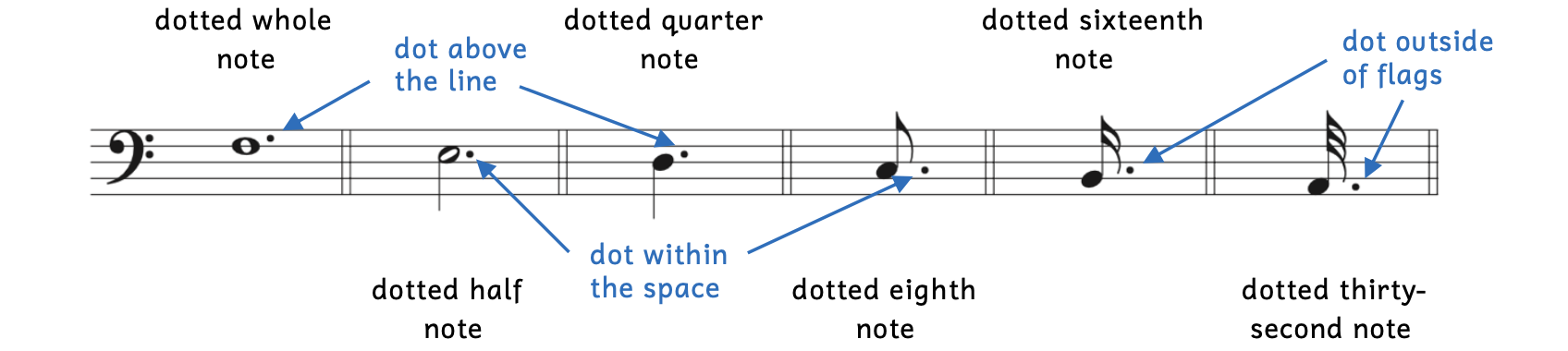

Dots must be precisely written on the staff.

Example 1.6.6. Dotted notes

- For notes on a line, the dot goes in the space above the line on which the notehead sits (see dotted whole note, dotted quarter note, and dotted sixteenth note).

- For notes in a space, the dot goes directly to the right of the notehead (see dotted half note, dotted eighth note, and dotted thirty-second note).

- For notes with flags, place the dot farther away from the notehead (see dotted eighth note, dotted sixteenth note, and dotted thirty-second note).

Dot placement might seem insignificant, but it is important.

- If you draw a dot on a line, it is likely to be hidden and unseen.

- If you draw a dot in the wrong place, another note might be held out longer than the one you intended.

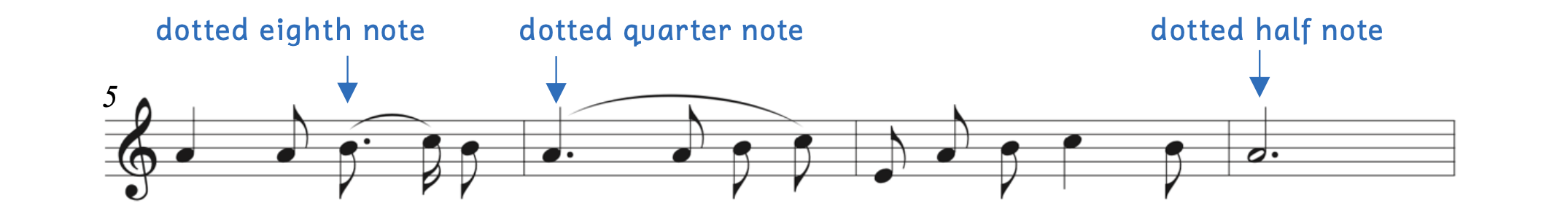

Example 1.6.7 shows dotted notes in context.

Example 1.6.7. Dotted notes: Brooman[5], “Den emsamna Makan”

- Brooman uses three different types of dotted notes: a dotted eighth note, a dotted quarter note, and a dotted half note.

- The placement of the dot for the dotted eighth note is above the line because the notehead falls on a line. The dots of the other two dotted notes fall in the space directly next to the notehead because the notehead is in a space.

Rests can also have dots and are used exactly the same way. The name of the rest has the word “dotted” added before it. For example, a quarter rest becomes a dotted quarter rest. Occasionally, you may come across two rests in row instead of a dotted rest (e.g., a quarter rest followed by an eighth rest instead of a dotted quarter rest).

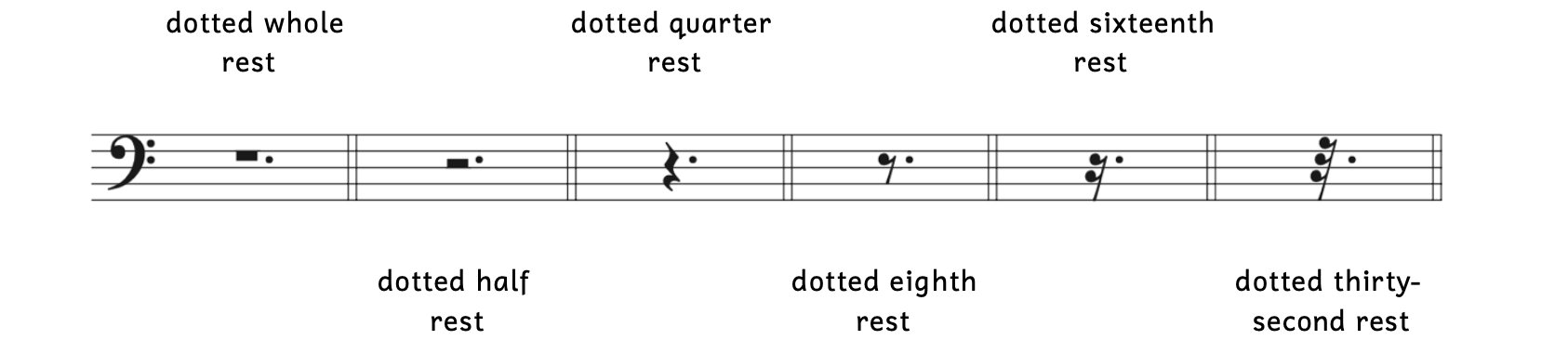

Example 1.6.8. Dotted rests

Notice the placement of the dots. Recall that for dotted notes, dots vary in placement depending on where the notehead lies. For dotted rests, dots are always placed in the third space (see Example 1.6.8).

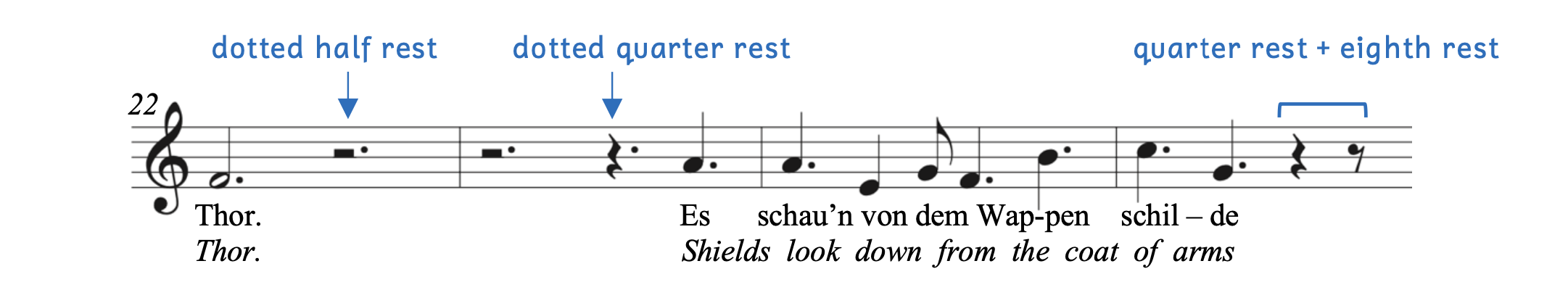

Example 1.6.9 shows several dotted rests in context.

Example 1.6.9. Dotted rests: Kinkel[6], “Das Schloss Boncourt”

- After the dotted half note, the example continues with two dotted half rests and one dotted quarter rest.

- As an alternate to the dotted quarter rest, the example concludes with a quarter rest followed by an eighth rest.

- In the actual score, the quarter rest and eighth rest appear as a dotted quarter rest. However, it has been written this way because you may come across two rests in a row like this, instead of a dotted rest.

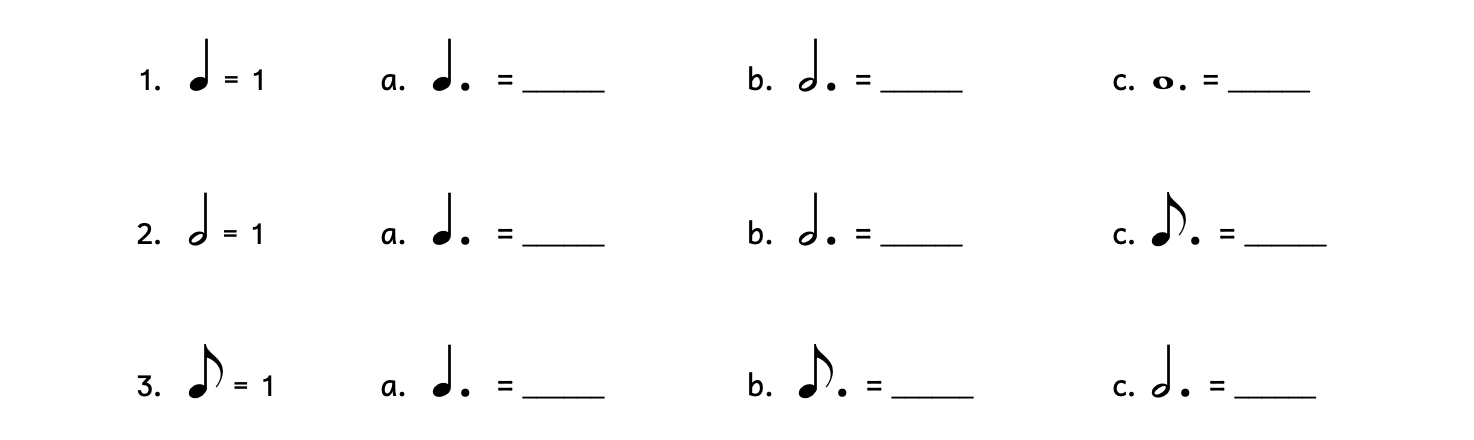

Practice 1.6. Calculating Dotted Note Values

Directions:

- Based on the given note that equals one, write the note values of the other notes. For a sample, see Example 1.6.4.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

1.7 GRAND STAFF

Read the pitches in the following example.

Example 1.7.1. Bass clef example

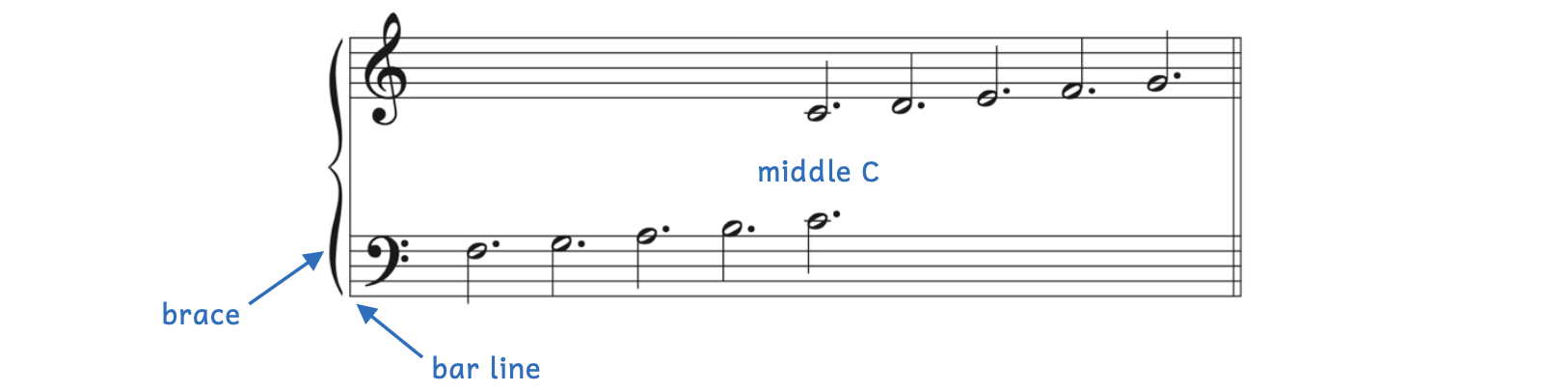

Although the first five notes may be easy to read, the next four may not be as easy. We can add ledger lines to notes higher than middle C in the bass clef, but an easier way to read these notes would be to read the first five notes in the bass clef and the last four notes in the treble clef. We can accomplish this by using a grand staff, which is when the treble clef and bass clef are used together at the same time.

Example 1.7.2. Grand staff

- It is essential that the grand staff begins with a brace and bar line. (Recall that when we wrote for only treble clef or only bass clef, there was no bar line at the beginning.) The brace and bar line are necessary at the start of a grand staff because both staves[7] must be read at the same time.

- Without the brace and bar line, the staff with the treble clef would be the first system and the staff with the bass clef would be the second system. In Example 1.7.2, the grand staff makes up one system.

- The grand staff is most commonly used by keyboard instruments, such as the piano. If you played Example 1.7.2 on the piano, your left hand would play F-G-A-B-C and your right hand would play C-D-E-F-G. You would only play middle C once, however, as it occurs simultaneously in both hands.

Example 1.7.3 is the opening of one of the most famous pieces written for the piano, Beethoven’s “Für Elise.” Ignore the unfamiliar parts for now, and only focus on the grand staff.

Example 1.7.3. Grand staff: Beethoven, “Für Elise,” WoO 59

The grand staff in Example 1.7.3 clearly shows which parts are to be played by the right hand and which parts are to be played by the left hand. The brace and bar line at the start of the grand staff reminds us that both staves are to be read simultaneously.

Grand Staff

The grand staff contains the treble clef and the bass clef. It begins with a brace and a bar line to show that both staves are read simultaneously.

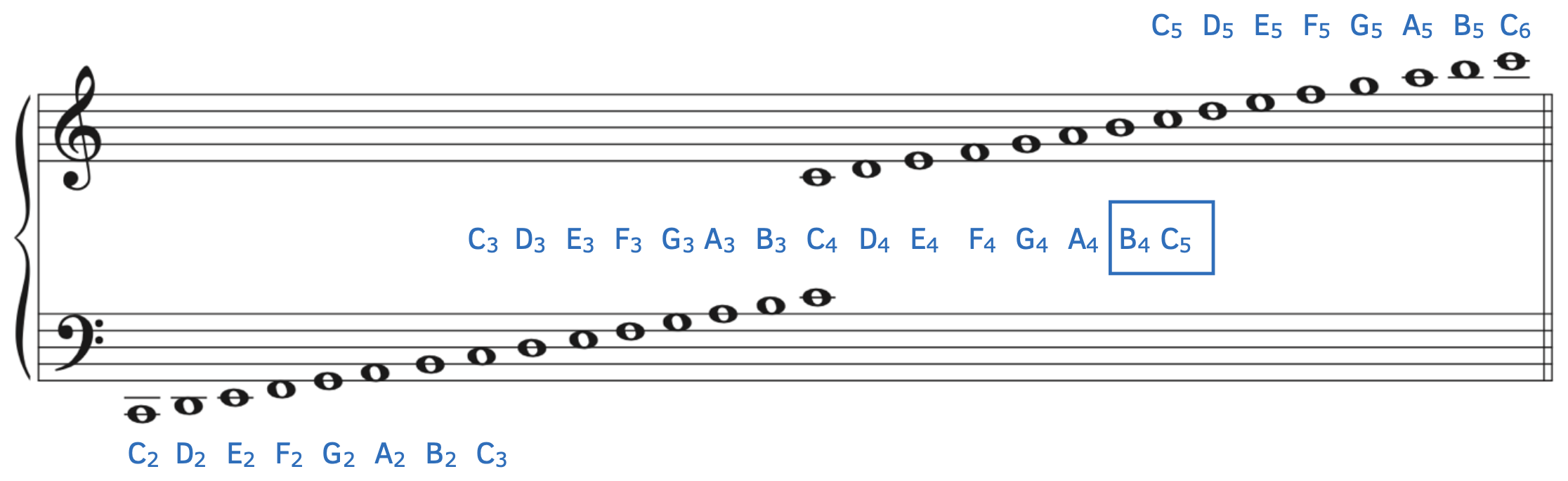

Octave Designation

As you learned, the musical alphabet repeats. It can be confusing and wordy to describe which specific note you are referring to: “The D on the fourth line of the treble clef.” To solve this problem, we use octave designations. Recall that an octave was the same note name eight notes apart. An octave designation is a subscript number placed to the right of the note name to specify exactly how high or low the note sounds (i.e.,where the note is on the keyboard. For example, middle C is also known as C4 (pronounced “C-4”).

Middle C is called C4 because there are eight Cs on a piano keyboard, and middle C is the fourth C. The lowest C is called C1, the next higher one is called C2, and so on. C4 is located approximately at the middle of the keyboard. “The D on the fourth line of the treble clef” would simply be referred to as D5.

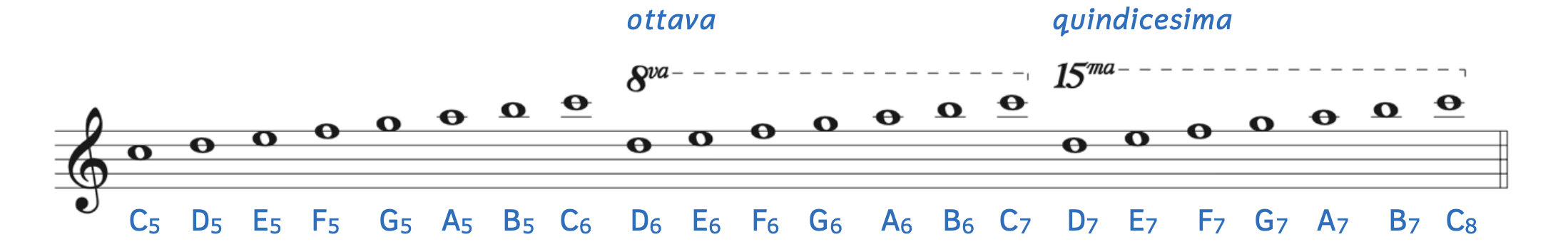

Example 1.7.4. Octave designations

Octave designations go as low as A0 and as high as C8 because a piano keyboard has 88 keys. However, the octave designations in Example 1.7.4 are the ones most commonly used.

Although the musical alphabet repeats after G (i.e., A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A…), the musical alphabet using octave designations changes with every C.

- This means that with every C, the octave designation is one number higher.

- In Example 1.7.4, observe the two pitches in the box (B4 and C5). B4 did not go to C4 because C4 is middle C, which is below B4. The note above B4 is C5.

- After Bx, the next note is Cx+1.

Octave Designation

- In order to know the exact pitch you are referring to, we use an octave designation.

- An octave designation is a subscript number to the right of the note name.

- Octave designation numbers change with C, so after B3 comes C4.

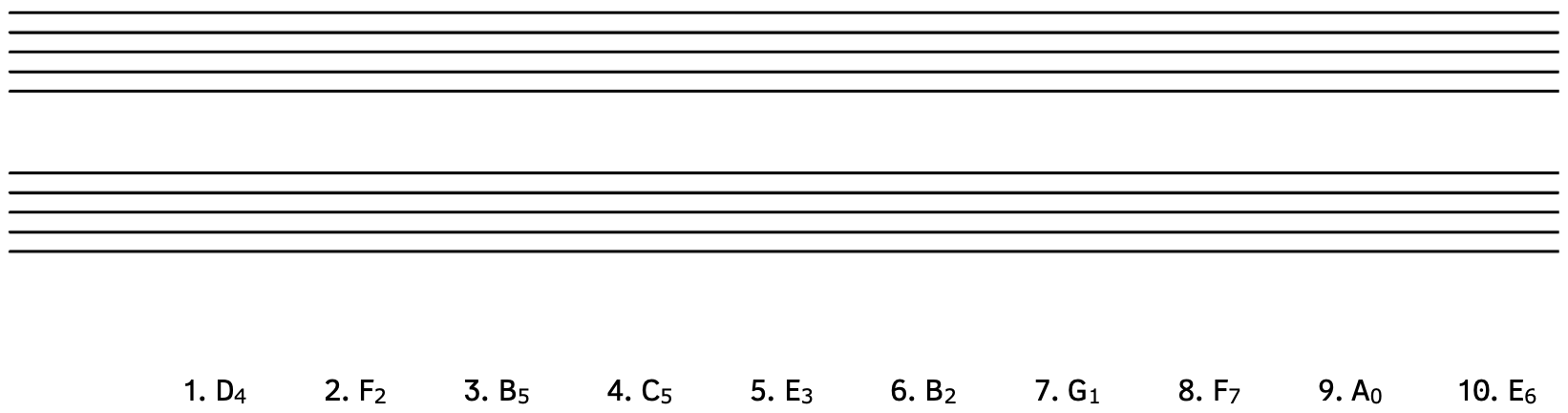

Practice 1.7A. Identifying Pitches with Octave Designations

Directions:

- Identify the pitches on the staff with octave designations. Be aware that the clef changes.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

Solution

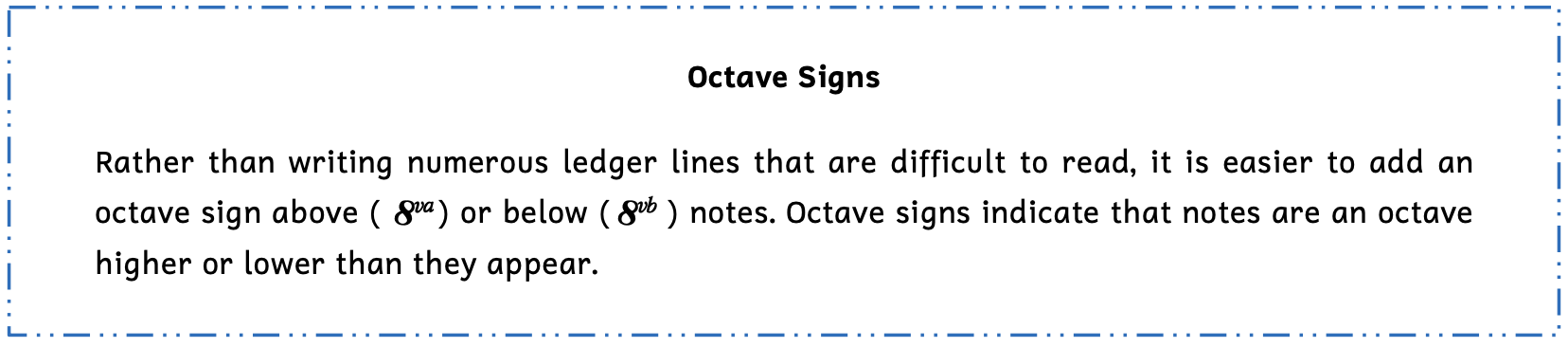

Octave Signs

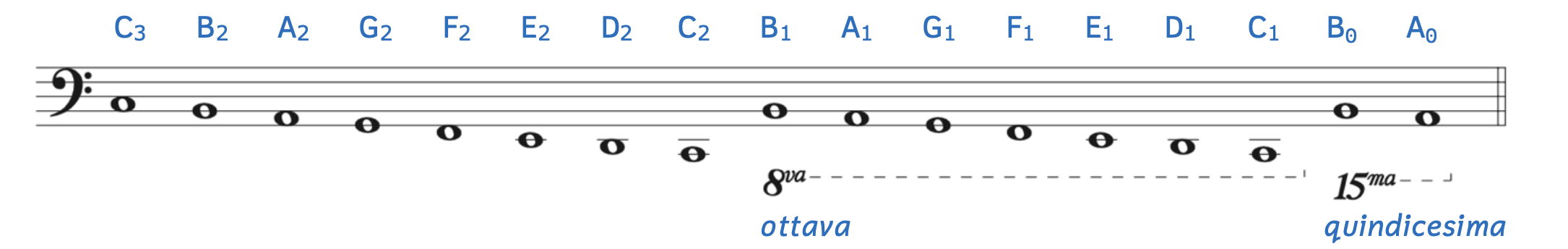

When writing notes below C2 or above C6, it is much easier to use octave signs rather than adding multiple ledger lines. Octave signs tell you to perform pitches an octave (or two) higher or lower than written.

Example 1.7.5. Octave signs above

- Ottava : 8va (ottava alta, or “octave above”) is written above and is followed by a dotted line to indicate which notes are to be performed an octave higher than they appear.

- Quindicesima : 15ma (“at the fifteenth”) is written above and is followed by a dotted line to indicate which notes are to be performed two octaves higher than they appear.

Without octave signs, you would need nine ledger lines to write C8! Octave signs below can be written the same way.

Example 1.7.6. Octave signs below

- Ottava: 8va is written below and is followed by a dotted line to indicate which notes are to be performed an octave lower than they appear.

- Quindicesima: 15ma is written below and is followed by a dotted line to indicate which notes are to be performed two octaves lower than they appear.

- Other ways to indicate an octave below is to write 8vb (ottava bassa or “octave below”) or 8va bassa below the notes.

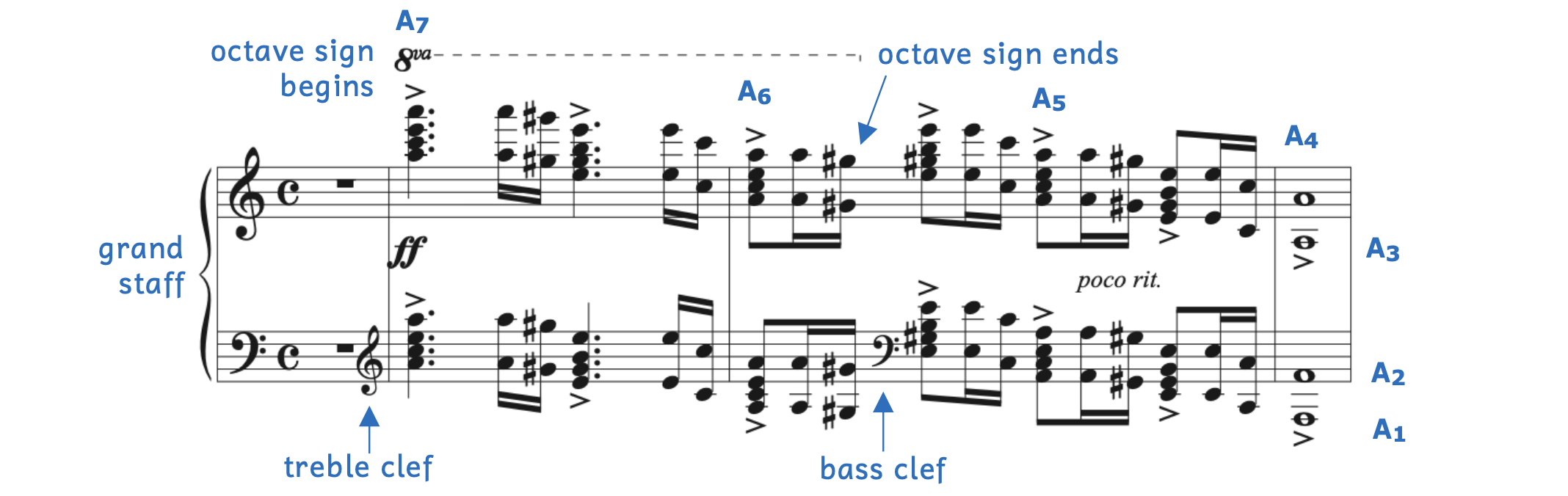

Example 1.7.7 shows the opening of Grieg’s famous Piano Concerto. Although there are a few items that may be unfamiliar to you, there are some new concepts we just learned. In particular, notice how Grieg is able to cover seven octaves on the piano in only three measures!

Example 1.7.7. Grieg[8], Piano Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 16, i

A concerto is a work for a soloist and orchestra. Example 1.7.7 begins with a measure of rest because the orchestra is performing (which is not shown), while the pianist waits. When the piano begins, the octave sign indicates that the highest note is an octave higher than A6. The example identifies the different As in different octaves.

Because the piano begins so high, the left hand’s part does not start with a bass clef, but rather, a treble clef. Although the grand staff typically begins with treble and bass clef, it is not uncommon to see two treble clefs (or two bass clefs). The bass clef makes its return halfway through the example, when the pianist’s left hand starts to move below the middle of the keyboard.

Practice 1.7B. Writing Pitches on a Grand Staff

Directions:

- In the staves below, write a grand staff and end with a double bar line.

- Using dotted eighth notes, write the given notes on the grand staff. Separate each example with a bar line.

- Add an octave sign if you exceed two ledger lines.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

1.8 ARTICULATION MARKS

Example 1.8.1 only contains quarter notes. However, not all these quarter notes are performed the same. This is because of the articulation marks, which are symbols applied to notes that tells the musician how to perform them.

Example 1.8.1. Articulation marks

- Staccato: Notes performed short.

- Staccatissimo: Notes performed even shorter than a staccato.

- Accent: Notes performed loud.

- Marcato: Notes performed even louder than an accent.

- Tenuto: Notes held out to their full value.

- Fermata: Notes held out longer than their full value.

- Slur: Notes held out to their full value with minimal silence between notes.

Notice that articulation marks are placed directly above or below the notehead, on the opposite side of the stem. The exceptions are the marcato and fermata, which are always placed above the note when there is only one voice.

Many of the words we use in music are Italian. When we use words in other languages, the words are italicized (e.g., tenuto). When we use words in English, the words are not italicized (e.g., accent).

There are several articulation marks that are not symbols, but abbreviations These are the sforzando markings, which are the same as accents.

Example 1.8.2. Sforzando

Sforzando is an articulation mark that means the note is to be accented (played loudly). The different letter abbreviations vary from forzato, forzando, and sforzato. The two abbreviations in blue in Example 1.8.2 are the two ways sforzando markings are most commonly seen.

Example 1.8.3 illustrates several different articulation marks in a short three-measure except.

Example 1.8.3. Farrenc[9], “Souvenir des Huguenots”

- Most of the notes are to be played staccato (short).

- In measure 6, there are accents on the quarter notes, which should be louder.

- In the last measure, there is a staccatissimo symbol (very short) as well as a sforzando symbol, which should be accented even louder.

Articulation Marks

Articulation marks are symbols that specify details about how to perform a note.

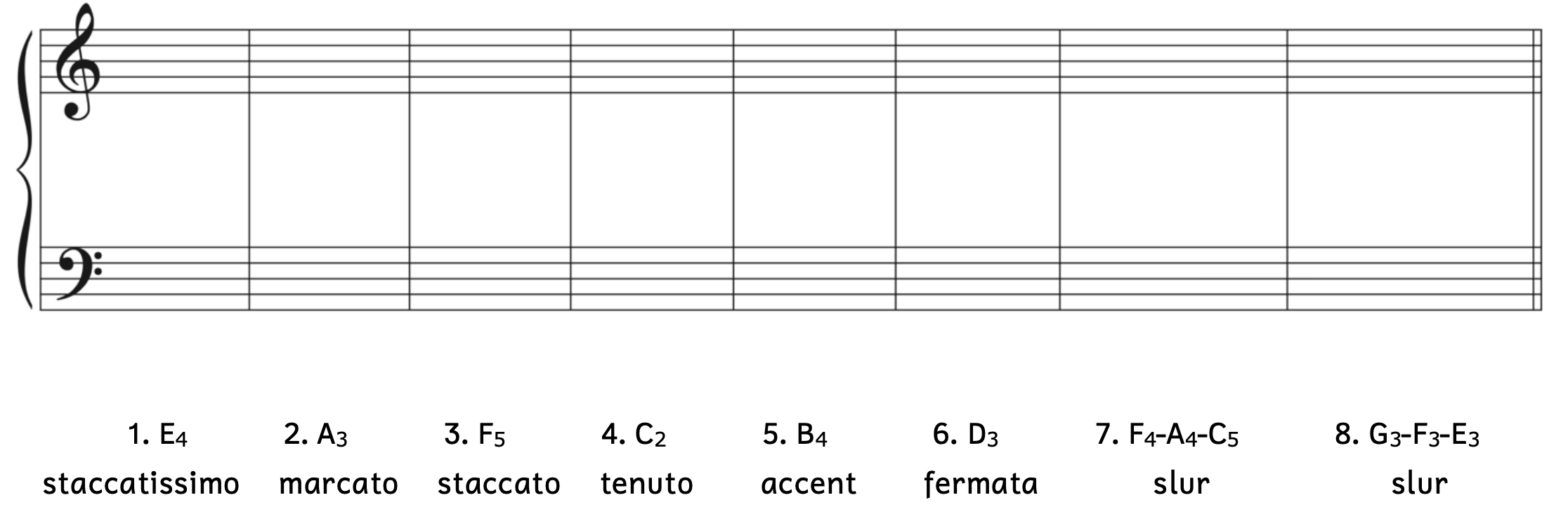

Practice 1.8. Writing Pitches with Articulation Marks

Directions:

- Using quarter notes, write the given notes with articulations on the grand staff.

Click here to watch the tutorial.

SUMMARY

-

-

- Musical sounds are represented by notes and silence is represented by rests. [1.1]

- The parts of a note include the notehead, stem, and flag. [1.1]

- There are different types of notes including the whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, and sixteenth note. [1.2]

- Each note can equal one, which determines the value of other notes. [1.2]

- Music is written on a musical staff. [1.3, 1.4, 1.7]

- The treble clef is used for higher-sounding voices/instruments.

- The bass clef is used for lower-sounding voices/instruments.

- The treble clef and bass clef occur simultaneously in the grand staff.

- There can be notes outside the staff. [1.7]

- If the notes occur just outside the staff, we use ledger lines.

- If the notes occur way beyond the staff, we use octave signs.

- Rests behave just as notes, but represent silence. [1.4]

- Dots add half the value of the note or rest to the note or rest. [1.6]

- Octave designations are subscript numbers that indicate exactly how high or low the pitch sounds. [1.7]

- Articulation marks (staccato, staccatissimo, accent, marcato, tenuto, fermata, slur) are symbols that tell the musician how to perform notes. [1.8]

-

TERMS

-

-

- articulation mark

- bar line

- bass clef

- brace

- clef

- dot (or augmentation dot)

- dotted note/rest

- double bar line

- eighth note/rest

- flag

- grand staff

- keyboard

- ledger line

- measure (or bar)

- measure number (or bar number)

- middle C

- musical alphabet

- notes/rests

- breve/breve rest (or double whole note/rest)

- whole note/rest

- half note/rest

- quarter note/rest

- eighth note/rest

- sixteenth note/rest

- thirty-second note/rest

- sixty-fourth note/rest

- note values

- notehead

- octave

- octave designation

- octave sign

- pitch

- rest values

- rests (see notes/rests)

- rhythm

- sforzando

- forzando

- forzato

- sforzato

- staff (musical staff)

- lines

- spaces

- staff paper

- stem

- system

- treble clef

-

- Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805-1847) was a German composer and pianist. Her brother was also a composer (Felix Mendelssohn). ↵

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was a German composer. ↵

- Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) was an Italian composer. ↵

- Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) was an Italian composer. ↵

- Hanna Brooman (1809-1887) was a Swedish composer. ↵

- Johanna Kinkel (1810-1858) was a German composer and writer. ↵

- The plural of staff is staves. ↵

- Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. ↵

- Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was a French composer and pianist. ↵

How musical sounds are heard as points in time

Symbols that represent how high or low sounds are

Musical symbols that represent silence

Note names

Letter names used for pitches; from A to G.

Distance between a pitch and the same pitch eight notes apart

Oval-shaped part of a note

Line connected to notehead

Shorter curved line(s) connected to the tip of the stem

Unfilled notehead without a stem

Unfilled notehead with a stem

Filled notehead with a stem

Filled notehead with a stem and one flag.

Filled notehead with a stem and two flags.

Set of five horizontal lines upon which notes are placed. Also called "staff."

Set of five horizontal lines upon which notes are placed. Also called "musical staff."

Symbol placed at the start of the staff that tells us the pitches

Specific type of clef that is placed at the beginning of the staff, used for higher-sounding voices and instruments.

Vertical line on a staff that breaks music into easy-to-understand segments called measures or bars.

Segment in music separated by bar lines; also called "bar."

Segment in music separated by bar lines; also called "measure."

A short line that represents a line on the staff if the staff were to continue (down or up) beyond its five lines.

Name of note commonly used to give a visual sense of location; centered approximately in the middle of a piano keyboard.

Specific type of bar line that has two closely-placed bar lines next to each other.

A line of music.

Numbering system for measures.

Symbols that represent silence

Note that is worth twice the value of a whole note; also called a "double whole note."

Note that is worth twice the value of a whole note; also called a "breve."

Filled notehead with stem and three flags; worth half the value of a sixteenth note.

Filled notehead with stem and four flags; worth half the value of a thirty-second note.

Rest that is worth twice the value of a whole rest; also called a "double whole rest."

Rest that is worth twice the value of a whole rest; also called a "breve rest."

Rest that hangs below the fourth line. It is worth twice as much as a half rest.

Rest that sits on the third line of the staff. It is worth half a whole rest and twice as much as a quarter rest.

Rest that is worth half a half rest and twice as much as an eighth rest

Rest that is worth half a quarter rest and twice as much as a sixteenth rest.

Rest that is worth half an eighth rest.

Rest with four flags; worth half the value of a thirty-second rest.

Symbol placed at the start of the staff that is used for lower-sounding voices and instruments.

Dot following notes or rests adds half the value of the note or rest.

Note with a dot following it. The dot adds half the value of the note.

Treble clef and bass clef connected together and to be played at the same time.

A subscript number placed to the right of the note name to specify exactly where the note is on the keyboard.

Symbols or abbreviations that tell you to perform pitches an octave (or two) higher or lower than written.

A symbol (8va) placed above pitches or below pitches to indicate notes should be played an octave higher or an octave lower.

A symbol (15ma) placed above pitches or below pitches to indicate notes should be played two octaves higher or a two octaves lower.

Symbol placed above or below a note that specifies how it should be performed.

Articulation mark of a dot placed above or below a notehead; note is to be played short.

Articulation mark placed above or below a notehead; note is to be played extremely short.

Articulation mark that looks like a "greater than" symbol placed above or below a notehead; note is to be played louder.

Articulation mark that looks like bold carets placed above or below a notehead; note is to be played even louder than an accent.

Articulation mark that looks like a short horizontal line placed above or below a notehead; note is to be played its full value.

Articulation mark that indicates to perform a note for longer than its value.

Articulation mark that looks like a curved line that indicates that notes are held out to their full value with minimal silence between notes.

Variation of accent marks.

Curved bracket at the beginning of a grand staff that connects treble clef and bass clef together.

piano keyboard

the white parts of a piano keyboard

Notes are performed an octave higher than written.

Notes are performed an octave lower than written.